Kanban at London's National Gallery

05 Nov 2013

So a few weeks ago I went to London’s National Gallery. I have very little interest in art, but occasionally find myself with someone who does, and there are worse ways to spend a few hours than looking at big paintings of people in funny hats. On this occasion there was a special exhibition on display. It contained some reasonable arts and one of the best queues I have ever had the privilege of standing in.

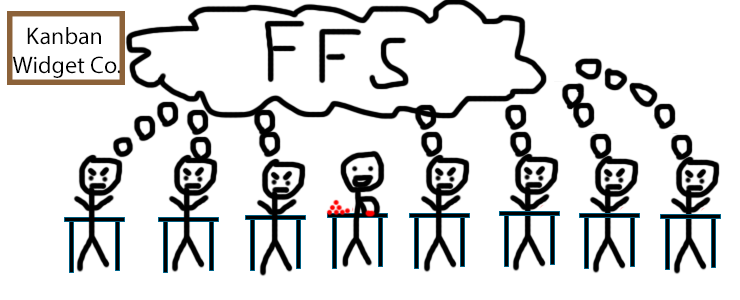

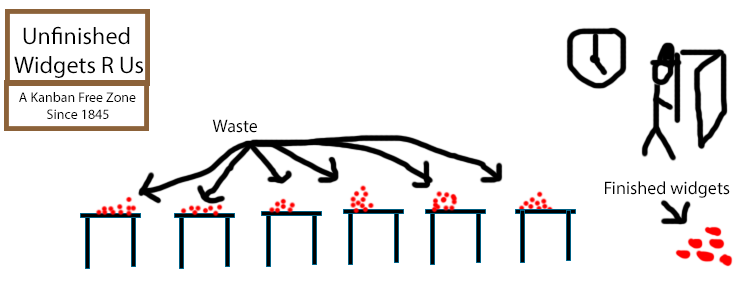

First, a quick explanation of Kanban. In its simplest form in Lean Manufacturing, a Kanban system acts as a physical constraint on the running of a Just In Time production line. For example, say there are 10 people on a production line building a widget. They pass a tray of components along the production line, each person assembling part of the system. The number of trays is limited to 10, so the guy at the start can only add another tray of parts and introduce another widget-to-be into the system when the guy at the end completes construction of a widget and sends the empty tray back to the start.

In Kanban, bottlenecks in the production line quickly reveal themselves.

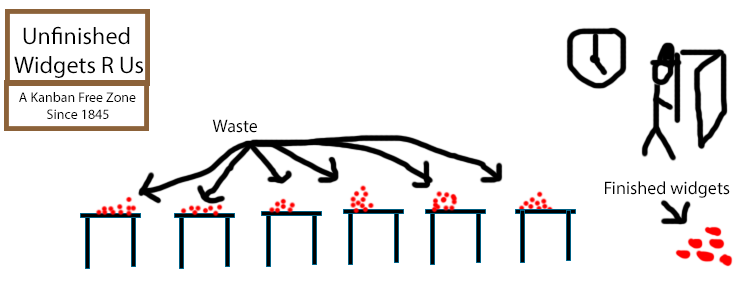

And you can never be left with a massive pile of unfinished widgets, as production line input is directly controlled by the rate of output.

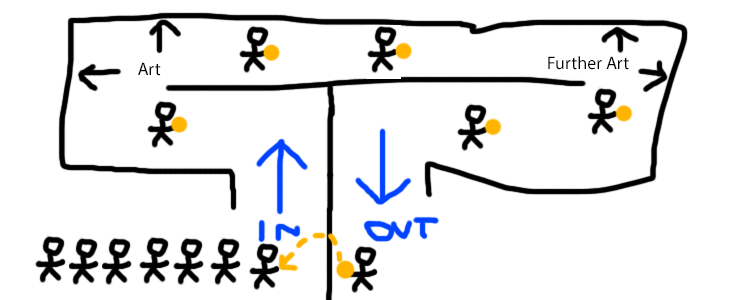

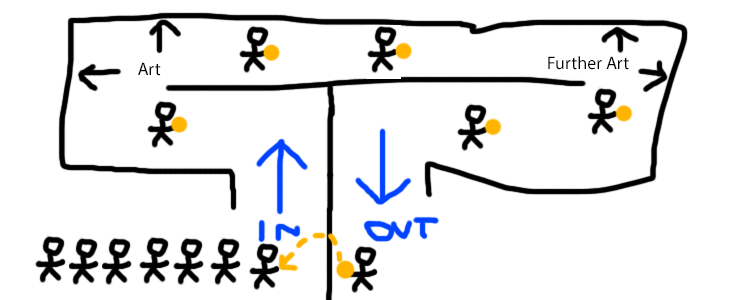

Back in the National Gallery, we reached the front of the queue, were each given a big orange disc, and let into the exhibition. We looked around some pretty intense sculptures of a monk smashing his own head in with a big rock. Finally we left the exhibit and gave an attendant our orange discs on our way out. These discs were transported 4m from the exit to the entrance, and given to the next lucky entrants.

This is such an elegantly Kanban way of controlling entry. If the exhibition can handle 20 people at once, you grab 20 orange discs and you’re good to go. If you want to change the number of people allowed in, simply add or remove discs from the pool. The attendants don’t even need to know what this number is - the single instruction they need to follow is “if you have a disc then give it to the next person in the queue and let them in”.

The capacity to make mistakes, particularly mistakes that don’t auto-correct themselves, is reduced to almost nil. Say a group of 5 accidentally sneak in with only 4 discs - there will be one extra person in the exhibit for the duration of their visit. But when they leave they will only give back 4 discs, so they will only be replaced by 4 people. The only way to screw things up permanently is if someone forgets to hand in a disc, but assuming that no one actively tries to steal them a gentle reminder from the exit attendant should prevent this.

There’s a startup/programming-based moral in here somewhere, but for once I don’t particularly want to find it. I just want to encourage you to visit the National Gallery and see their exquisite queueing system - it’s well worth a trip.

So a few weeks ago I went to London’s National Gallery. I have very little interest in art, but occasionally find myself with someone who does, and there are worse ways to spend a few hours than looking at big paintings of people in funny hats. On this occasion there was a special exhibition on display. It contained some reasonable arts and one of the best queues I have ever had the privilege of standing in.

First, a quick explanation of Kanban. In its simplest form in Lean Manufacturing, a Kanban system acts as a physical constraint on the running of a Just In Time production line. For example, say there are 10 people on a production line building a widget. They pass a tray of components along the production line, each person assembling part of the system. The number of trays is limited to 10, so the guy at the start can only add another tray of parts and introduce another widget-to-be into the system when the guy at the end completes construction of a widget and sends the empty tray back to the start.

In Kanban, bottlenecks in the production line quickly reveal themselves.

And you can never be left with a massive pile of unfinished widgets, as production line input is directly controlled by the rate of output.

Back in the National Gallery, we reached the front of the queue, were each given a big orange disc, and let into the exhibition. We looked around some pretty intense sculptures of a monk smashing his own head in with a big rock. Finally we left the exhibit and gave an attendant our orange discs on our way out. These discs were transported 4m from the exit to the entrance, and given to the next lucky entrants.

This is such an elegantly Kanban way of controlling entry. If the exhibition can handle 20 people at once, you grab 20 orange discs and you’re good to go. If you want to change the number of people allowed in, simply add or remove discs from the pool. The attendants don’t even need to know what this number is - the single instruction they need to follow is “if you have a disc then give it to the next person in the queue and let them in”.

The capacity to make mistakes, particularly mistakes that don’t auto-correct themselves, is reduced to almost nil. Say a group of 5 accidentally sneak in with only 4 discs - there will be one extra person in the exhibit for the duration of their visit. But when they leave they will only give back 4 discs, so they will only be replaced by 4 people. The only way to screw things up permanently is if someone forgets to hand in a disc, but assuming that no one actively tries to steal them a gentle reminder from the exit attendant should prevent this.

There’s a startup/programming-based moral in here somewhere, but for once I don’t particularly want to find it. I just want to encourage you to visit the National Gallery and see their exquisite queueing system - it’s well worth a trip.