Mathematicians hate civil liberties: 100 prisoners and 100 boxes

13 Jan 2014

Hypothetical prisoners are the great unspoken shame of our civilisation. Incarcerated inside sinister “mathematics departments” all over the world, their “crimes” are universally vague in nature and rarely even specified, and they are constantly taunted with unnecessarily difficult ways in which to try and gain their freedom. The scandalous treatment of these innocent casualties of circumstance is just one of the reasons why it can be so hard to distinguish between a Kafka-esque totalitarian nightmare and a maths degree.

0. Question

This week’s disenfranchised victims of the system appear to have it particularly bad, but as always they have been given the traditional, single, excruciatingly contrived chance of salvation.

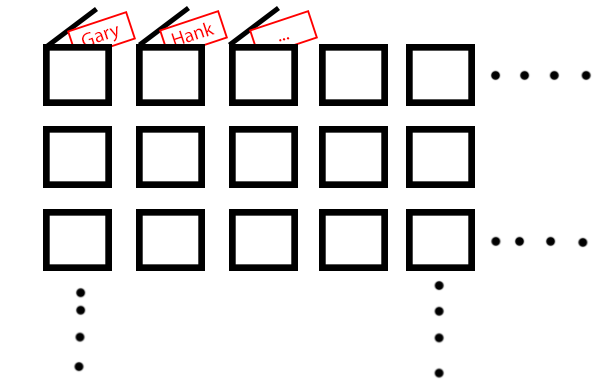

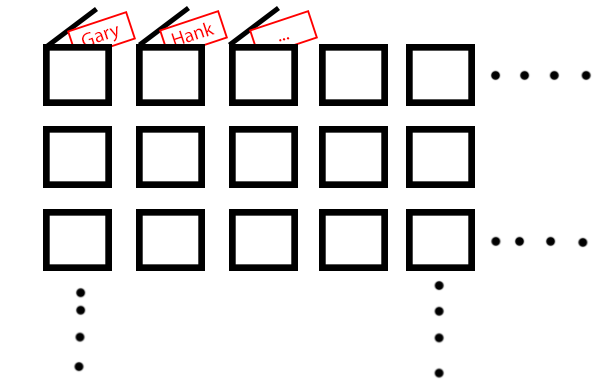

There are 100 prisoners. There is a sealed room with a 10x10 grid of 100 closed boxes in, and inside each box is a piece of paper with a different prisoner’s name on it. All the prisoners have different names. They will be sent into the room one by one. Each prisoner will go in, open a box, look at the name inside, and close the box. He will repeat this process 50 times in total, then leave the room. He must leave the room exactly as he found it, and cannot communicate with the other prisoners in any way whilst in the room or once he has left. If every prisoner at some point opens the box with his own name in, then they all get to go free. If any of them fail, they will all be executed.

The night before, they are allowed to gather together and decide on a strategy. But they still seem to be pretty boned. Each prisoner has a 50% chance of finding their own name, and so overall they would appear to have a 0.5^100 = 7.89 * 10^(-29)% chance of going free. With these odds, if they had started playing this game at the dawn of time, and had managed to play it a quadrillion times per second until the present day, their chances of winning even once would still be negligible.

Is there anything they can do to give themselves a fighting chance of success, say >30%?

1. Answer

The short but stupid answer is yes, obviously there is, otherwise this question would be a waste of time and pixels.

The less stupid answer:

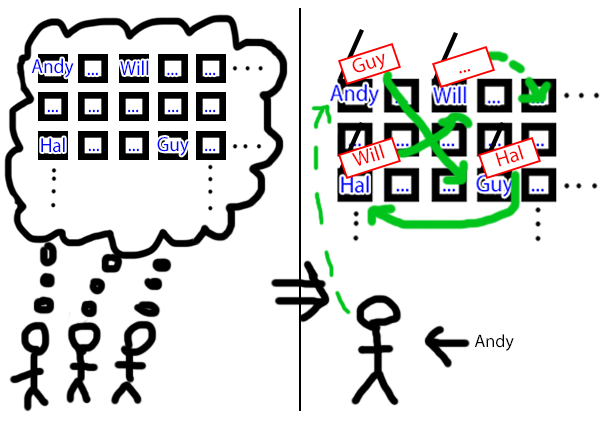

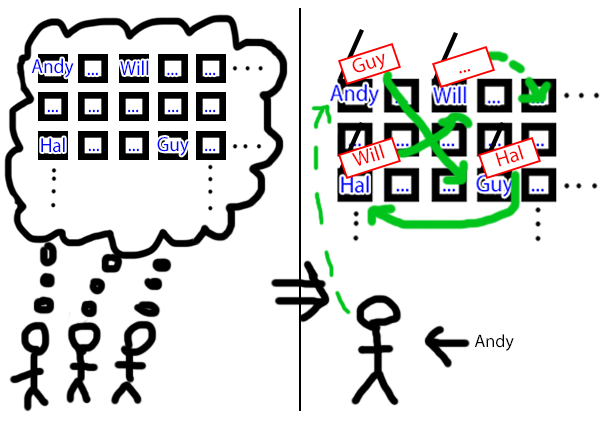

The prisoners collectively decide on and commit to memory a random mapping between their names and the boxes, completely unrelated to which box contains which name (information that they obviously don’t know anyway). So Andy maps to one box, Guy to another, Hal to another, etc. Each prisoner first opens the box assigned to their name by this random mapping. Then they open the box that maps to the name they found inside their first box. Then the one mapping to the name inside that one. Then the one mapping to the name inside that one. And so on until they either find their own name (hooray) or until they have unsuccessfully opened 50 boxes and get shot (boo). By following this strategy they have a 30.7% chance of all finding their own names and surviving. Easy.

2. Say what?

At first and second glances, this is bananas.

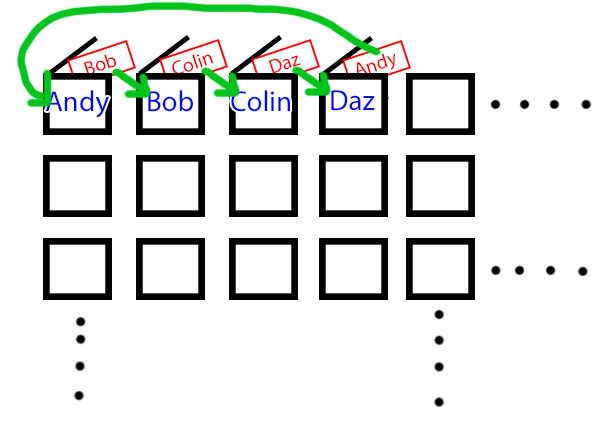

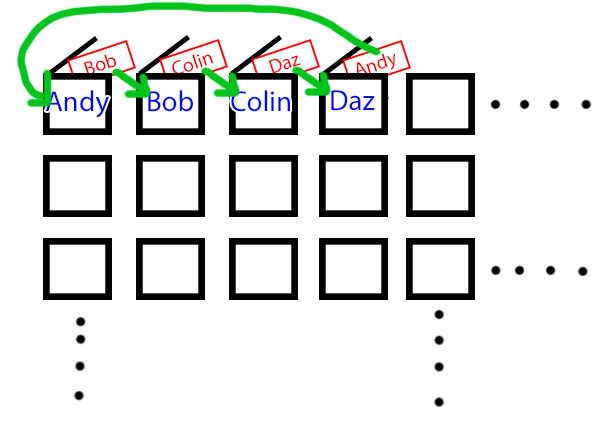

But like any good rollercoaster, it all comes down to loops. Let’s say the boxes that the prisoners decide map to Andy, Bob, Colin and Daz all coincidentally turn out to lead in a loop. This would mean that if a prisoner opens the box that the prisoners have randomly decided maps to Andy, he finds the name “Bob”. When he then opens the box that maps to Bob, he finds the name “Colin”. When he opens the box that maps to Colin, he finds the name “Daz”, and when he opens the box that maps to Derek, he finds the name Andy. He has already opened Andy’s box, so we have a loop of length 4.

If this prisoner is one of Andy, Bob, Colin or Daz, he will have successfully found his own name, and everything is on track. If he is anyone else and he continues to follow the algorithm, then he will go round in circles forever and all the prisoners are doomed. However, Andy, Bob, Colin or Daz are the only prisoners who will ever get onto this loop in the first place! They will start by opening the box that maps to their name, and then proceed as above. Since each name only appears in one box, there is no way to cut into the loop unless you started on it. So in this case, we know for certain that Andy, Bob, Colin and Daz will all find their own names after opening exactly 4 boxes, and that no other prisoners will ever open these boxes.

In fact, if a prisoner follows this strategy then the only way he can fail to find his own name is if the box it is in turns out to be part of a loop >=51 boxes in length. Suppose a prisoner’s name is in a box that is part of a loop of length 68. By the algorithm, the first box the prisoner opens is the one that maps to his own name. So the box that actually contains his name must be one step back in the loop, which will be the 68th box that he will try opening. Unfortunately he will of course be thrown to the sharks after his first 50 attempts, so in this case the prisoners are in trouble. Nonetheless, if all loops have length 50 or less (say there are 3 loops that are 48, 39 and 13 boxes long), then all the prisoners will definitely find their own names and they will all be released.

So the question “what is the prisoners’ probability of survival?” becomes “what is the probability that there are no loops longer than 50 boxes?”

We will start by working out the probability that a random arrangement of n boxes contains a loop of length k, where n/2 < k <= n.

Using simple combinatorics there are n C k = (n!) / ((n-k)!*k!) ways to pick the boxes that will form our loop. There are (k-1)! ways to order them to create the loop, and then (n-k)! ways to order the rest of the boxes that don’t form part of the loop. This gives a number of ways of arranging the boxes and names such that there exists a loop of length k of (n!) / ((n-k)!*k!) * (k-1)! * (n-k)! = (n!) / k.

There are a total of n! possible ways of arranging all the boxes. So the probability that there exists a loop of length k is (n!) / (k*(n!)) = 1/k, which is fascinatingly independent of n, the total number of boxes (it really is worth thinking for a few seconds about how cool this is).

We now want the probability that there exists no loop of length > 50 out of our collection of 100 boxes. Since there can be at most 1 such loop, we simply add together the probabilities that there does exist a loop of length 51, 52…100, and subtract this from 1.

This gives a probability of there existing no loop of length > 50 of 1 - 1/100 - 1/99 - … - 1/51 = 30.7%. Which is somewhat larger than 7.89 * 10^(-29)%.

3.1 Extensions

-

What is actually going on here? Have the individual prisoners become more likely to their own names?

-

Suppose all the prisoners who have been through the room are allowed to communicate. Can this group ever be certain that they are safe before they have seen everyone find their own name? If so, what is the soonest that they could ever know that they were safe?

-

If a friendly prison warden is able to sneak in before the rigmarole starts and switch the names in 2 boxes, how much help is he able to give the prisoners?

3.2 More answers

-

Nope. Before any of the prisoners have gone into the room, the probability that a given prisoner will find their own name is of course still exactly 50%. However, the prisoners’ strategy has the effect of massively bunching together the successes and failures of the individual prisoners. If Andy goes in and finds his own name after traversing a loop of length 18, he can immediately know for certain that every prisoner whose name he saw will also find their own name. Conversely, if his own name turns out to be part of a loop of length 53, and so he doesn’t find it, none of the other 52 prisoners in this loop will find their own name either. However, since it only takes a single miss for the group to be screwed, 53 failures are no worse than 1 and so the prisoners are bunching and burying these extra failures. As we have seen, the effect of this is incredibly powerful.

-

As soon as 50 prisoners find their own names, the prisoners know for certain that they have won without needing any more information. These 50 names are not part of a loop of length > 50, and obviously the remaining 50 names also can’t be part of a loop of length > 50. In fact, if the first prisoner finds his own name after traversing a loop of 50 boxes, he immediately knows that they are safe for similar reasons.

-

He can always completely ensure their safety, as he will always be able to make a switch that cuts any big loop that might exist. Even in the worst case where all the boxes are arranged in a single loop of length 100, he can simply switch the names inside of the 50th and 100th boxes in this loop. Box 50 will now point back to box 1, so boxes 1-50 form up an acceptable loop of length 50, and box 100 now points to box 51, so boxes 51-100 also form a similarly friendly loop.

4. Conclusion

Not quite suitable for the dinner table unless you happen to be eating next to a large whiteboard, but still absolutely beautiful. The solution even seems obvious with hindsight, as it’s essentially the only way for the prisoners to co-ordinate their choices in any way beyond blind luck. In theory there could be be variations on this box-pointer theme that offer even better chances of success, but theory is no match for Curtin, Warshauer, 2006, which proved that the relatively simple strategy above is in fact optimal. So if you find yourself at the mercy of a despotic mathematician without the benefit of a handy blunt object, you know exactly what to do.

You’re welcome.

5. References

Hypothetical prisoners are the great unspoken shame of our civilisation. Incarcerated inside sinister “mathematics departments” all over the world, their “crimes” are universally vague in nature and rarely even specified, and they are constantly taunted with unnecessarily difficult ways in which to try and gain their freedom. The scandalous treatment of these innocent casualties of circumstance is just one of the reasons why it can be so hard to distinguish between a Kafka-esque totalitarian nightmare and a maths degree.

0. Question

This week’s disenfranchised victims of the system appear to have it particularly bad, but as always they have been given the traditional, single, excruciatingly contrived chance of salvation.

There are 100 prisoners. There is a sealed room with a 10x10 grid of 100 closed boxes in, and inside each box is a piece of paper with a different prisoner’s name on it. All the prisoners have different names. They will be sent into the room one by one. Each prisoner will go in, open a box, look at the name inside, and close the box. He will repeat this process 50 times in total, then leave the room. He must leave the room exactly as he found it, and cannot communicate with the other prisoners in any way whilst in the room or once he has left. If every prisoner at some point opens the box with his own name in, then they all get to go free. If any of them fail, they will all be executed.

The night before, they are allowed to gather together and decide on a strategy. But they still seem to be pretty boned. Each prisoner has a 50% chance of finding their own name, and so overall they would appear to have a 0.5^100 = 7.89 * 10^(-29)% chance of going free. With these odds, if they had started playing this game at the dawn of time, and had managed to play it a quadrillion times per second until the present day, their chances of winning even once would still be negligible.

Is there anything they can do to give themselves a fighting chance of success, say >30%?

1. Answer

The short but stupid answer is yes, obviously there is, otherwise this question would be a waste of time and pixels.

The less stupid answer:

The prisoners collectively decide on and commit to memory a random mapping between their names and the boxes, completely unrelated to which box contains which name (information that they obviously don’t know anyway). So Andy maps to one box, Guy to another, Hal to another, etc. Each prisoner first opens the box assigned to their name by this random mapping. Then they open the box that maps to the name they found inside their first box. Then the one mapping to the name inside that one. Then the one mapping to the name inside that one. And so on until they either find their own name (hooray) or until they have unsuccessfully opened 50 boxes and get shot (boo). By following this strategy they have a 30.7% chance of all finding their own names and surviving. Easy.

2. Say what?

At first and second glances, this is bananas.

But like any good rollercoaster, it all comes down to loops. Let’s say the boxes that the prisoners decide map to Andy, Bob, Colin and Daz all coincidentally turn out to lead in a loop. This would mean that if a prisoner opens the box that the prisoners have randomly decided maps to Andy, he finds the name “Bob”. When he then opens the box that maps to Bob, he finds the name “Colin”. When he opens the box that maps to Colin, he finds the name “Daz”, and when he opens the box that maps to Derek, he finds the name Andy. He has already opened Andy’s box, so we have a loop of length 4.

If this prisoner is one of Andy, Bob, Colin or Daz, he will have successfully found his own name, and everything is on track. If he is anyone else and he continues to follow the algorithm, then he will go round in circles forever and all the prisoners are doomed. However, Andy, Bob, Colin or Daz are the only prisoners who will ever get onto this loop in the first place! They will start by opening the box that maps to their name, and then proceed as above. Since each name only appears in one box, there is no way to cut into the loop unless you started on it. So in this case, we know for certain that Andy, Bob, Colin and Daz will all find their own names after opening exactly 4 boxes, and that no other prisoners will ever open these boxes.

In fact, if a prisoner follows this strategy then the only way he can fail to find his own name is if the box it is in turns out to be part of a loop >=51 boxes in length. Suppose a prisoner’s name is in a box that is part of a loop of length 68. By the algorithm, the first box the prisoner opens is the one that maps to his own name. So the box that actually contains his name must be one step back in the loop, which will be the 68th box that he will try opening. Unfortunately he will of course be thrown to the sharks after his first 50 attempts, so in this case the prisoners are in trouble. Nonetheless, if all loops have length 50 or less (say there are 3 loops that are 48, 39 and 13 boxes long), then all the prisoners will definitely find their own names and they will all be released.

So the question “what is the prisoners’ probability of survival?” becomes “what is the probability that there are no loops longer than 50 boxes?”

We will start by working out the probability that a random arrangement of n boxes contains a loop of length k, where n/2 < k <= n.

Using simple combinatorics there are n C k = (n!) / ((n-k)!*k!) ways to pick the boxes that will form our loop. There are (k-1)! ways to order them to create the loop, and then (n-k)! ways to order the rest of the boxes that don’t form part of the loop. This gives a number of ways of arranging the boxes and names such that there exists a loop of length k of (n!) / ((n-k)!*k!) * (k-1)! * (n-k)! = (n!) / k.

There are a total of n! possible ways of arranging all the boxes. So the probability that there exists a loop of length k is (n!) / (k*(n!)) = 1/k, which is fascinatingly independent of n, the total number of boxes (it really is worth thinking for a few seconds about how cool this is).

We now want the probability that there exists no loop of length > 50 out of our collection of 100 boxes. Since there can be at most 1 such loop, we simply add together the probabilities that there does exist a loop of length 51, 52…100, and subtract this from 1.

This gives a probability of there existing no loop of length > 50 of 1 - 1/100 - 1/99 - … - 1/51 = 30.7%. Which is somewhat larger than 7.89 * 10^(-29)%.

3.1 Extensions

-

What is actually going on here? Have the individual prisoners become more likely to their own names?

-

Suppose all the prisoners who have been through the room are allowed to communicate. Can this group ever be certain that they are safe before they have seen everyone find their own name? If so, what is the soonest that they could ever know that they were safe?

-

If a friendly prison warden is able to sneak in before the rigmarole starts and switch the names in 2 boxes, how much help is he able to give the prisoners?

3.2 More answers

-

Nope. Before any of the prisoners have gone into the room, the probability that a given prisoner will find their own name is of course still exactly 50%. However, the prisoners’ strategy has the effect of massively bunching together the successes and failures of the individual prisoners. If Andy goes in and finds his own name after traversing a loop of length 18, he can immediately know for certain that every prisoner whose name he saw will also find their own name. Conversely, if his own name turns out to be part of a loop of length 53, and so he doesn’t find it, none of the other 52 prisoners in this loop will find their own name either. However, since it only takes a single miss for the group to be screwed, 53 failures are no worse than 1 and so the prisoners are bunching and burying these extra failures. As we have seen, the effect of this is incredibly powerful.

-

As soon as 50 prisoners find their own names, the prisoners know for certain that they have won without needing any more information. These 50 names are not part of a loop of length > 50, and obviously the remaining 50 names also can’t be part of a loop of length > 50. In fact, if the first prisoner finds his own name after traversing a loop of 50 boxes, he immediately knows that they are safe for similar reasons.

-

He can always completely ensure their safety, as he will always be able to make a switch that cuts any big loop that might exist. Even in the worst case where all the boxes are arranged in a single loop of length 100, he can simply switch the names inside of the 50th and 100th boxes in this loop. Box 50 will now point back to box 1, so boxes 1-50 form up an acceptable loop of length 50, and box 100 now points to box 51, so boxes 51-100 also form a similarly friendly loop.

4. Conclusion

Not quite suitable for the dinner table unless you happen to be eating next to a large whiteboard, but still absolutely beautiful. The solution even seems obvious with hindsight, as it’s essentially the only way for the prisoners to co-ordinate their choices in any way beyond blind luck. In theory there could be be variations on this box-pointer theme that offer even better chances of success, but theory is no match for Curtin, Warshauer, 2006, which proved that the relatively simple strategy above is in fact optimal. So if you find yourself at the mercy of a despotic mathematician without the benefit of a handy blunt object, you know exactly what to do.

You’re welcome.