Reproducible beliefs

17 Nov 2018

If I find a belief that I can’t account for, I usually assume that it came from a marketer at Pepsi. This would explain why I find brown acid so refreshing, and why I believe so strongly in Kendall Jenner’s ability to bring clarity and soda to even the most fractious of conflicts.

As grateful as I am to Pepsi for the free education and life-affirming fizzy drinks, I do prefer to know where my beliefs came from. I’d ideally like them to be completely reproducible. I’d like to have a list of all the things I believe, together with the books, conversations, and other sources that have made me believe them. I’d like to be able to take a blank human, feed them my sources, and have them come to the same conclusions that I have. I spend a lot of time trying to capture and arrange information from books that I have read. My desire for reproducible beliefs is a big part of why.

It’s possible that “reproducible beliefs” is just a seven-dollar-fifty way of saying “citation needed”, but I think there’s more to it than that. The idea of reproducibility crops up in a lot of other places too, and is especially popular in software engineering. For example, I used to work on Machine Learning (ML) Infrastructure. My team built the tools used by data scientists to train ML models. Our holy grail, and the holy grail of any ML-Infra team, was to eventually build a reproducible training pipeline. If the legends are true, such a pipeline would record the exact datasets and configuration options used to train a model. When re-run with those same datasets and configuration options, it would deterministically re-produce the exact same model as it did the first time.

This property is extremely valuable. Reproducible ML pipelines allow model trainers to ensure that they truly understand an existing model before they try to improve it. If a model trainer produces an improved version of a model, then without a reproducible pipeline they can’t be certain where this improvement came from. Was it their hard work? Was it a configuration parameter that they changed by accident? Or was it because they were inadvertently using a subtly different dataset? Before trying to make a better model, a trainer wants to ensure that they fully understand the old one.

If your beliefs are reproducible, you can help people fully understand why you hold them. They can see why their outputs differ from yours. “Oh I see, I believe that government spending is much more efficient than you do.” I’m not an idiot and I know that this is almost never how discussions work, but maybe it could be, sometimes.

Back to ML. Without a reproducible training pipeline, your models become fragile, precious things. If one gets deleted or corrupted then you can never get it back. You might be able to use your non-reproducible pipeline to recreate something roughly similar, and sometimes this might be good enough. But sometimes your larger system will have grown to rely on the idiosyncrasies of your old model, and “roughly similar” will not do. If you have a reproducible pipeline, you simply rerun it with the same parameters that generated your model the first time, and the exact same model pops out the other end.

In theory, reproducible beliefs have a similar benefit. If you fall into a wood chipper then your loved ones will have greater anguishes to deal with than the loss of your nuanced positions on Universal Basic Income. But it’s still nice to know that they, unlike you, can be reconstructed.

Nowadays I work on computer security. We don’t train ML models, so we don’t care about reproducible pipelines, but boy do we care about reproducible builds.

Humans write programs as human-readable files of programming language source code. They usually look something like func run(int n, string input) { ...do_some_stuff()... } and so on. However, in many programming languages, this source code is not what a computer looks at when it runs a program. Instead, it first compiles the source code into a build artifact, and then executes that. A build artifact consists of low-level machine code, which is almost completely meaningless to a human, but makes total sense to a computer.

A lot of software is open source, which means that the source code is readily available on the internet for anyone to read and analyze. One of the benefits of open source software is that users and communities can check its code for security flaws, including deliberate backdoors that a malicious author might try to sneak past their users.

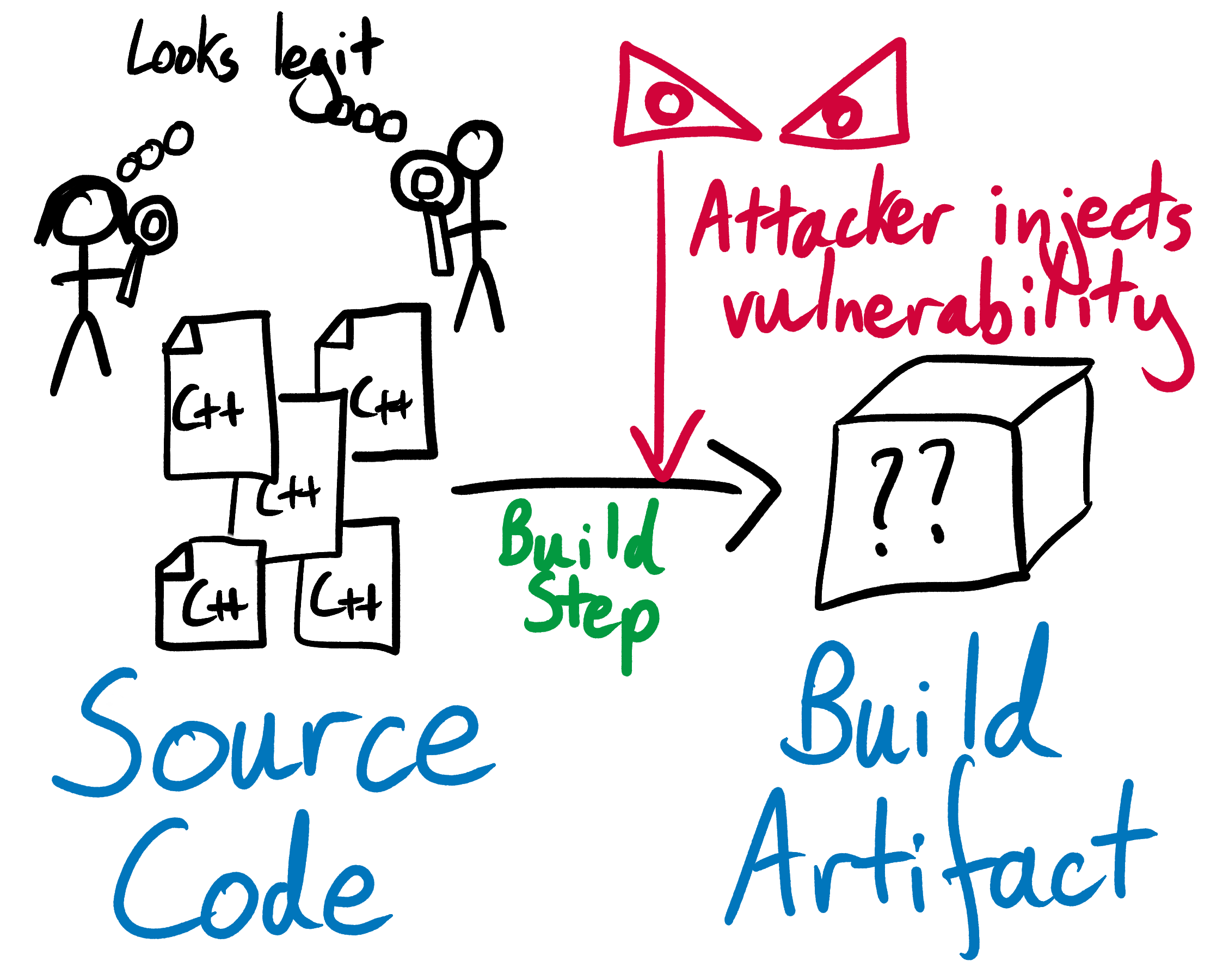

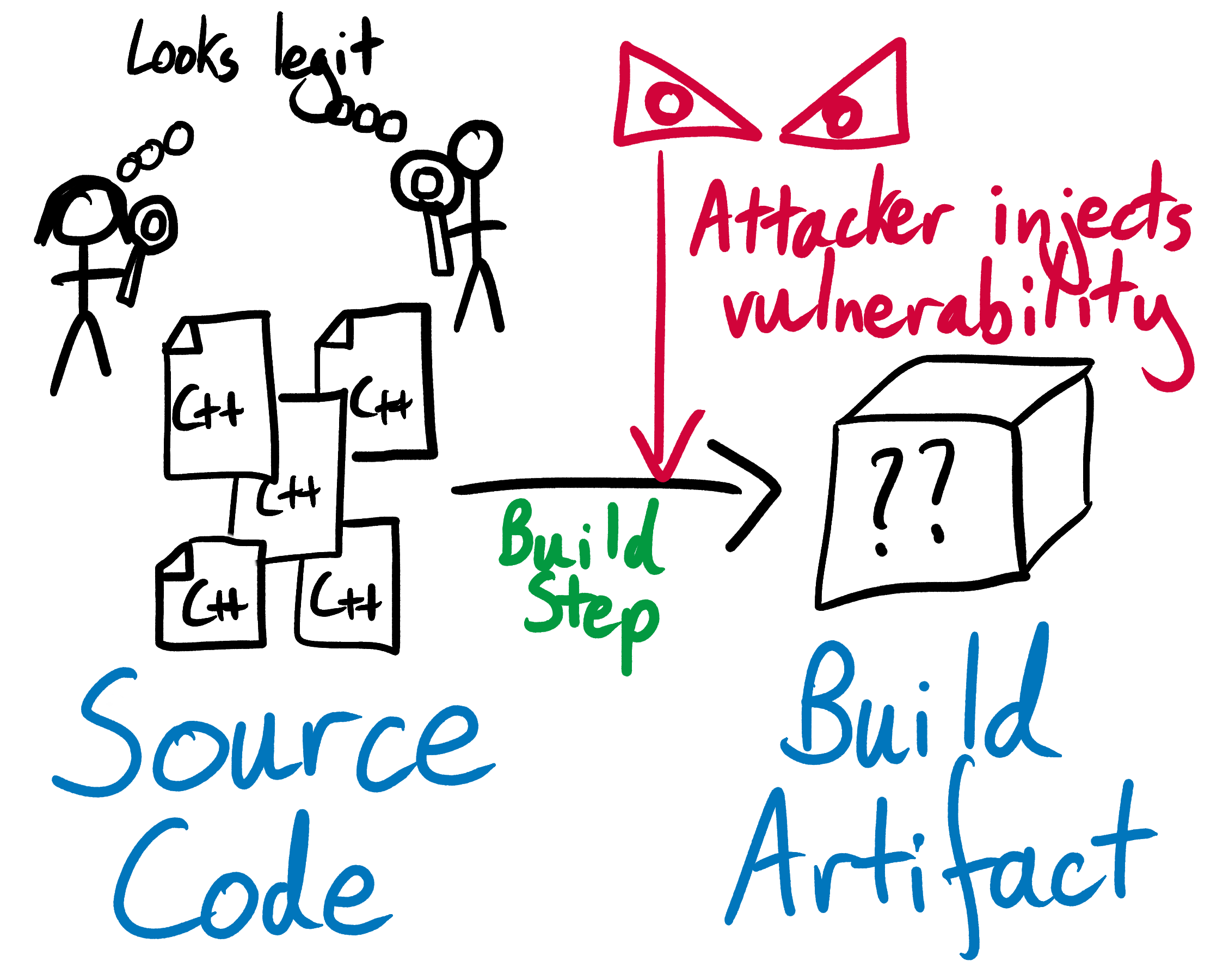

However, a lot of open source software is distributed as a compiled build artifact. Since a build artifact is made out of unintelligible machine code, its contents can’t easily be read and inspected by a human in the same way that source code can. This leaves users open to skullduggery during the build step, as there is no way to guarantee that the program that they are running was really generated from the verified open source code. It also leaves open source project maintainers vulnerable to blackmail and threats from malicious third-parties who want to force them to inject security holes into their software during the build step.

Reproducible builds save the day, protecting both users and maintainers. A project with a reproducible build declares up front all of the processes, settings, and dependencies required to turn its source code into a build artifact. Anyone who builds the project, at any time, on any machine that conforms to the build specification, should end up with the exact same output. The project maintainer will often still distribute a pre-built artifact for user convenience, but now the integrity of this artifact can be verified. If a prospective user runs the reproducible build and produces a different artifact to the one being distributed by the maintainer, they immediately know that something is wrong.

Reproducible builds prevent other people from duping you. Reproducible beliefs do too. The claim “I believe that corporation tax should be abolished because of this 2015 speech by the Dalai Lama” can be easily verified and debunked (I assume, I haven’t watched the speech myself). “I believe that corporation tax should be abolished because of some stuff I’ve read” cannot.

Reproducible beliefs also protect you from duping yourself. If your beliefs are truly reproducible then you should re-derive those same beliefs every time you go back over their source material. If, on the other hand, you re-watch the Dalai Lama’s speech on fiscal policy and find his arguments less persuasive than you remember, you know that your beliefs need re-evaluating. (once again, I haven’t watched this speech, which is fine because it’s obviously not real anyway)

A final fringe benefit of reproducible beliefs is that if you get hit by Bourne Identity-style amnesia then you don’t have to re-calculate what you think about gun control laws. You simply re-read all of the recorded inputs into your reproducible beliefs, and you’ll quickly regenerate your old conclusions as though nothing had happened.

Reproducible beliefs are of course an impossible goal, both practically and theoretically. There’s no such thing as a blank, emotionless human (apart from Nicholas Cage), and no one ever goes mechanically and deterministically from input material to completely evidence-based beliefs. No one’s hardware is the same, and questions of ethics and guts will always produce different answers on different systems for reasons that can never be fully specified.

But I still think that reproducible beliefs are a good ideal to aim for.

If I find a belief that I can’t account for, I usually assume that it came from a marketer at Pepsi. This would explain why I find brown acid so refreshing, and why I believe so strongly in Kendall Jenner’s ability to bring clarity and soda to even the most fractious of conflicts.

As grateful as I am to Pepsi for the free education and life-affirming fizzy drinks, I do prefer to know where my beliefs came from. I’d ideally like them to be completely reproducible. I’d like to have a list of all the things I believe, together with the books, conversations, and other sources that have made me believe them. I’d like to be able to take a blank human, feed them my sources, and have them come to the same conclusions that I have. I spend a lot of time trying to capture and arrange information from books that I have read. My desire for reproducible beliefs is a big part of why.

It’s possible that “reproducible beliefs” is just a seven-dollar-fifty way of saying “citation needed”, but I think there’s more to it than that. The idea of reproducibility crops up in a lot of other places too, and is especially popular in software engineering. For example, I used to work on Machine Learning (ML) Infrastructure. My team built the tools used by data scientists to train ML models. Our holy grail, and the holy grail of any ML-Infra team, was to eventually build a reproducible training pipeline. If the legends are true, such a pipeline would record the exact datasets and configuration options used to train a model. When re-run with those same datasets and configuration options, it would deterministically re-produce the exact same model as it did the first time.

This property is extremely valuable. Reproducible ML pipelines allow model trainers to ensure that they truly understand an existing model before they try to improve it. If a model trainer produces an improved version of a model, then without a reproducible pipeline they can’t be certain where this improvement came from. Was it their hard work? Was it a configuration parameter that they changed by accident? Or was it because they were inadvertently using a subtly different dataset? Before trying to make a better model, a trainer wants to ensure that they fully understand the old one.

If your beliefs are reproducible, you can help people fully understand why you hold them. They can see why their outputs differ from yours. “Oh I see, I believe that government spending is much more efficient than you do.” I’m not an idiot and I know that this is almost never how discussions work, but maybe it could be, sometimes.

Back to ML. Without a reproducible training pipeline, your models become fragile, precious things. If one gets deleted or corrupted then you can never get it back. You might be able to use your non-reproducible pipeline to recreate something roughly similar, and sometimes this might be good enough. But sometimes your larger system will have grown to rely on the idiosyncrasies of your old model, and “roughly similar” will not do. If you have a reproducible pipeline, you simply rerun it with the same parameters that generated your model the first time, and the exact same model pops out the other end.

In theory, reproducible beliefs have a similar benefit. If you fall into a wood chipper then your loved ones will have greater anguishes to deal with than the loss of your nuanced positions on Universal Basic Income. But it’s still nice to know that they, unlike you, can be reconstructed.

Nowadays I work on computer security. We don’t train ML models, so we don’t care about reproducible pipelines, but boy do we care about reproducible builds.

Humans write programs as human-readable files of programming language source code. They usually look something like func run(int n, string input) { ...do_some_stuff()... } and so on. However, in many programming languages, this source code is not what a computer looks at when it runs a program. Instead, it first compiles the source code into a build artifact, and then executes that. A build artifact consists of low-level machine code, which is almost completely meaningless to a human, but makes total sense to a computer.

A lot of software is open source, which means that the source code is readily available on the internet for anyone to read and analyze. One of the benefits of open source software is that users and communities can check its code for security flaws, including deliberate backdoors that a malicious author might try to sneak past their users.

However, a lot of open source software is distributed as a compiled build artifact. Since a build artifact is made out of unintelligible machine code, its contents can’t easily be read and inspected by a human in the same way that source code can. This leaves users open to skullduggery during the build step, as there is no way to guarantee that the program that they are running was really generated from the verified open source code. It also leaves open source project maintainers vulnerable to blackmail and threats from malicious third-parties who want to force them to inject security holes into their software during the build step.

Reproducible builds save the day, protecting both users and maintainers. A project with a reproducible build declares up front all of the processes, settings, and dependencies required to turn its source code into a build artifact. Anyone who builds the project, at any time, on any machine that conforms to the build specification, should end up with the exact same output. The project maintainer will often still distribute a pre-built artifact for user convenience, but now the integrity of this artifact can be verified. If a prospective user runs the reproducible build and produces a different artifact to the one being distributed by the maintainer, they immediately know that something is wrong.

Reproducible builds prevent other people from duping you. Reproducible beliefs do too. The claim “I believe that corporation tax should be abolished because of this 2015 speech by the Dalai Lama” can be easily verified and debunked (I assume, I haven’t watched the speech myself). “I believe that corporation tax should be abolished because of some stuff I’ve read” cannot.

Reproducible beliefs also protect you from duping yourself. If your beliefs are truly reproducible then you should re-derive those same beliefs every time you go back over their source material. If, on the other hand, you re-watch the Dalai Lama’s speech on fiscal policy and find his arguments less persuasive than you remember, you know that your beliefs need re-evaluating. (once again, I haven’t watched this speech, which is fine because it’s obviously not real anyway)

A final fringe benefit of reproducible beliefs is that if you get hit by Bourne Identity-style amnesia then you don’t have to re-calculate what you think about gun control laws. You simply re-read all of the recorded inputs into your reproducible beliefs, and you’ll quickly regenerate your old conclusions as though nothing had happened.

Reproducible beliefs are of course an impossible goal, both practically and theoretically. There’s no such thing as a blank, emotionless human (apart from Nicholas Cage), and no one ever goes mechanically and deterministically from input material to completely evidence-based beliefs. No one’s hardware is the same, and questions of ethics and guts will always produce different answers on different systems for reasons that can never be fully specified.

But I still think that reproducible beliefs are a good ideal to aim for.