HP printers try to send data back to HP about your devices and what you print

15 Sep 2019

Last week my in-laws politely but firmly asked me to set up their new HP printer. I protested that I’m completely clueless about that sort of thing, despite my tax-return-job-title of “software engineer”. Still remonstrating, I was gently bundled into their study with an instruction pamphlet, a cup of tea, a promise to unlock the door once I’d printed everyone’s passport forms, and a warning not to try the window because the roof tiles are very loose.

At first the setup process was so simple that even a computer programmer could do it. But then, after I had finished removing pieces of cardboard and blue tape from the various drawers of the machine, I noticed that the final step required the downloading of an app of some sort onto a phone or computer. This set off my crapware detector.

It’s possible that I was being too cynical. I suppose that it was theoretically possible that the app could have been a thoughtfully-constructed wizard, which did nothing more than gently guide non-technical users through the sometimes-harrowing process of installing and testing printer drivers. It was at least conceivable that it could then quietly uninstall itself, satisfied with a simple job well done.

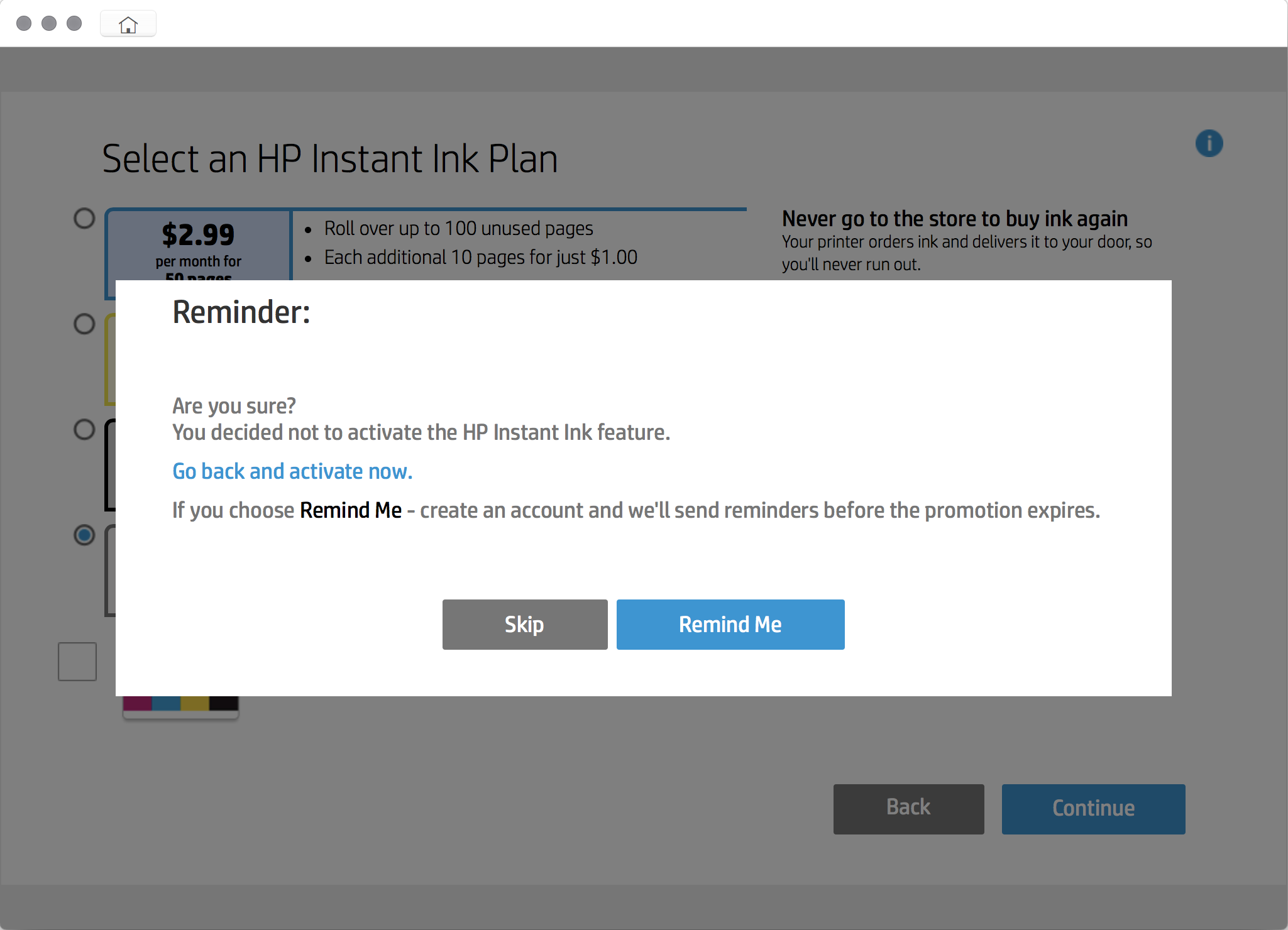

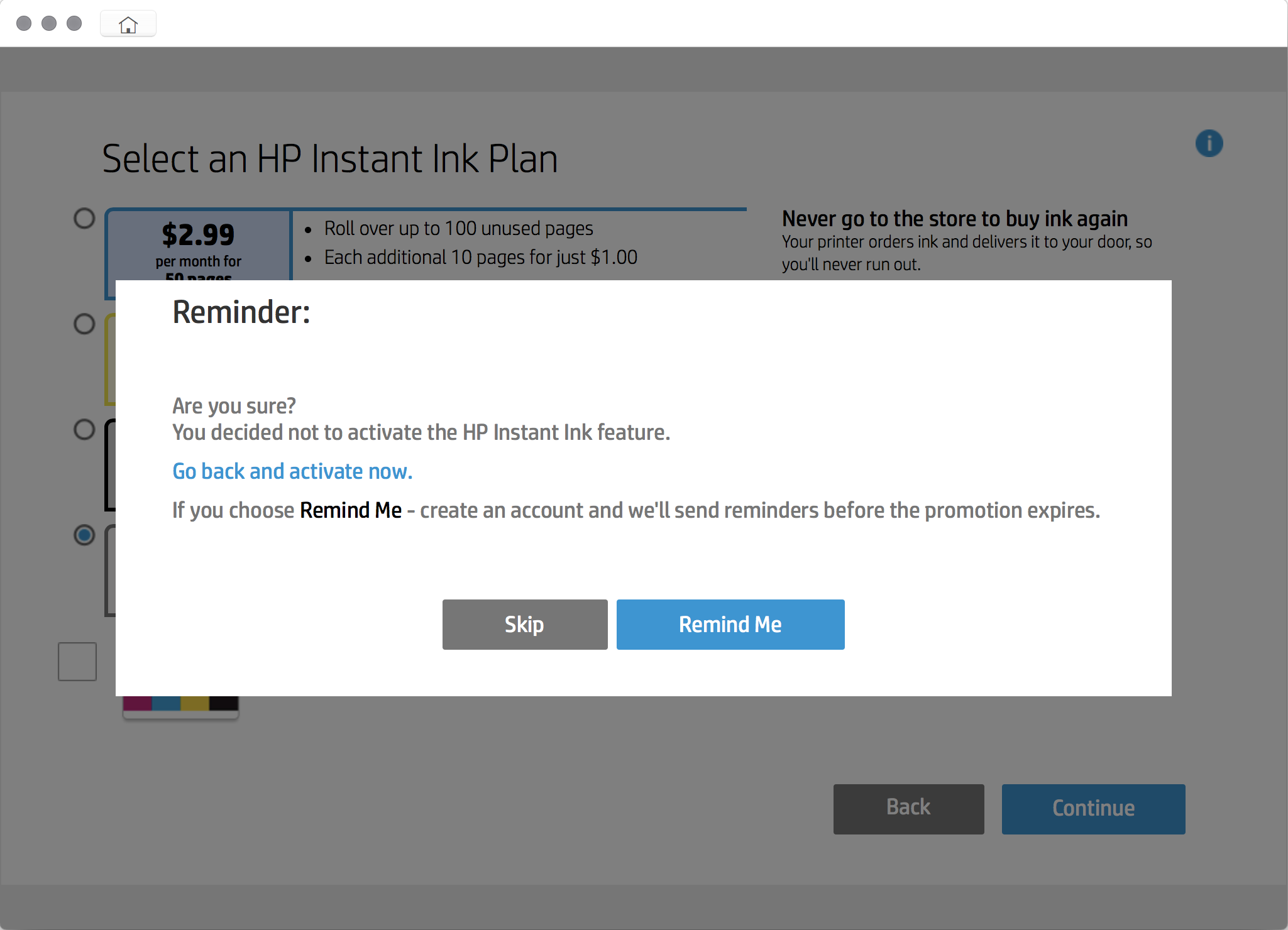

Of course, in reality it was a way to try and get people to sign up for expensive ink subscriptions and/or hand over their email addresses, plus something even more nefarious that we’ll talk about shortly (there were also some instructions for how to download a printer driver tacked onto the end). This was a shame, but not unexpected. I’m sure that the HP ink department is saddled with aggressive sales quotas, and no doubt the only way to hit them is to ruthlessly exploit people who don’t know that third-party cartridges are just as good as HP’s and are much cheaper. Fortunately, the careful user can still emerge unscathed from this phase of the setup process by gingerly navigating the UI patterns that presumably do fool some people who aren’t paying attention.

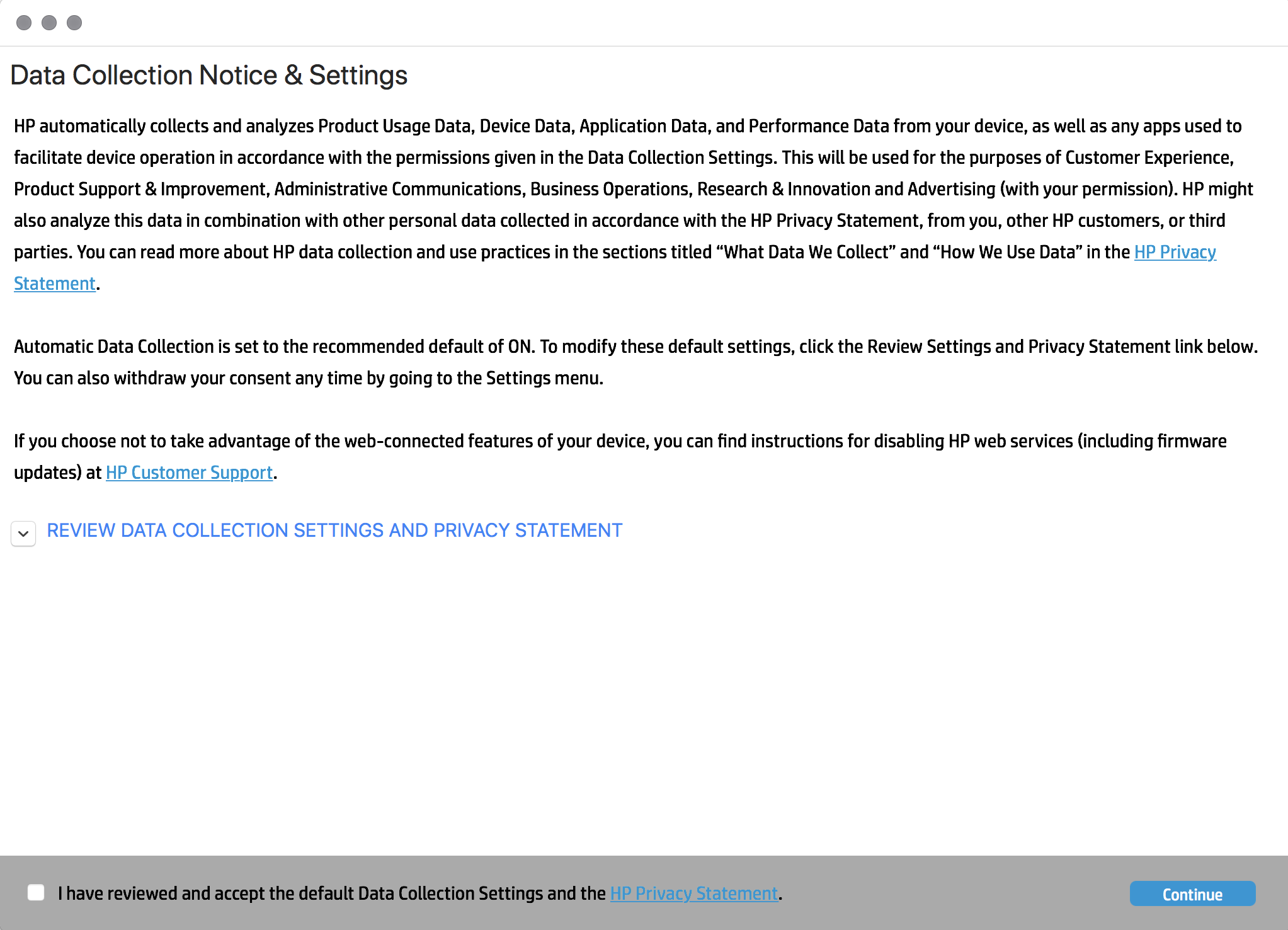

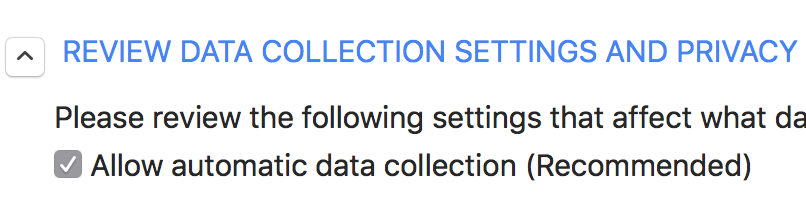

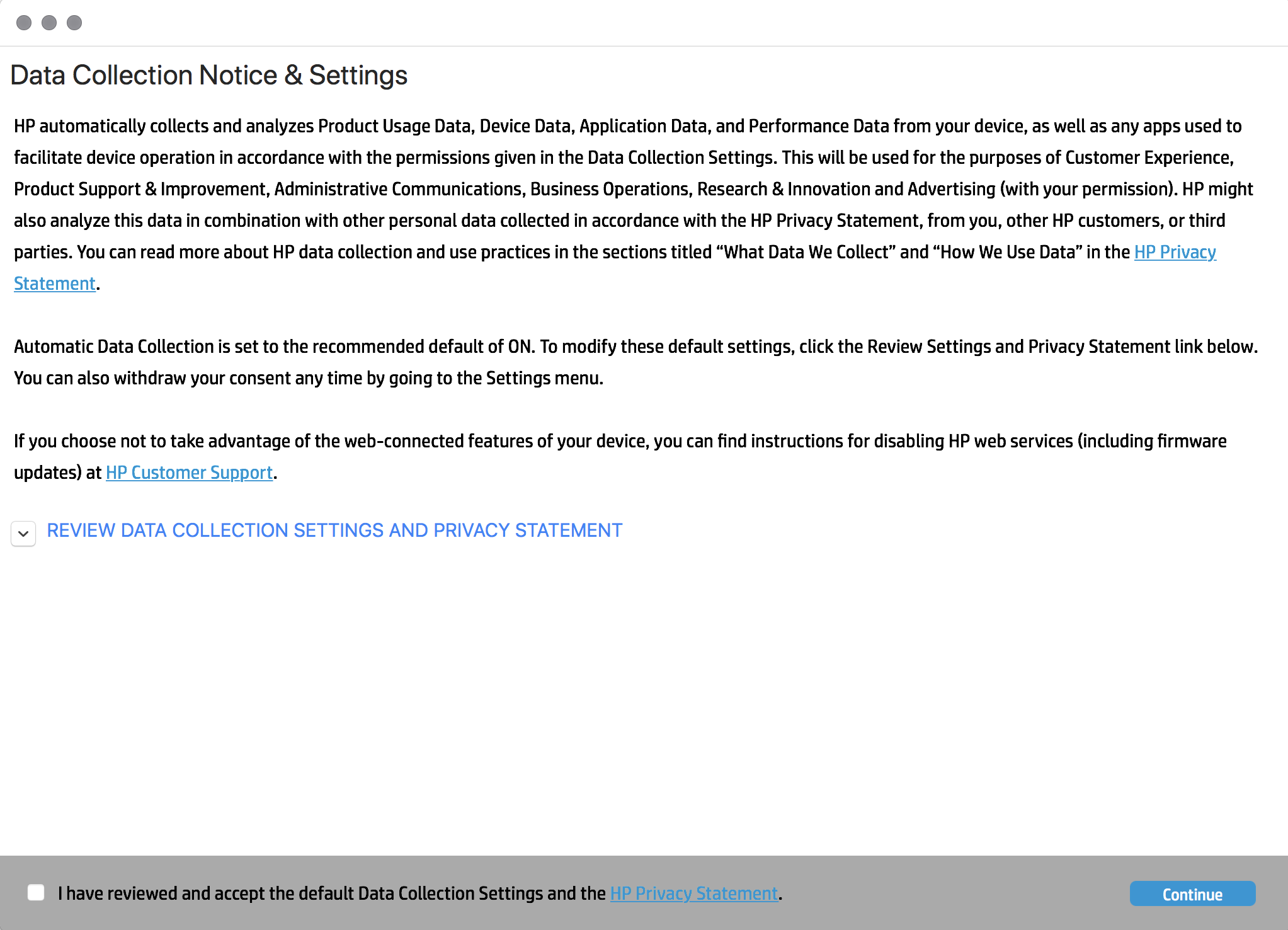

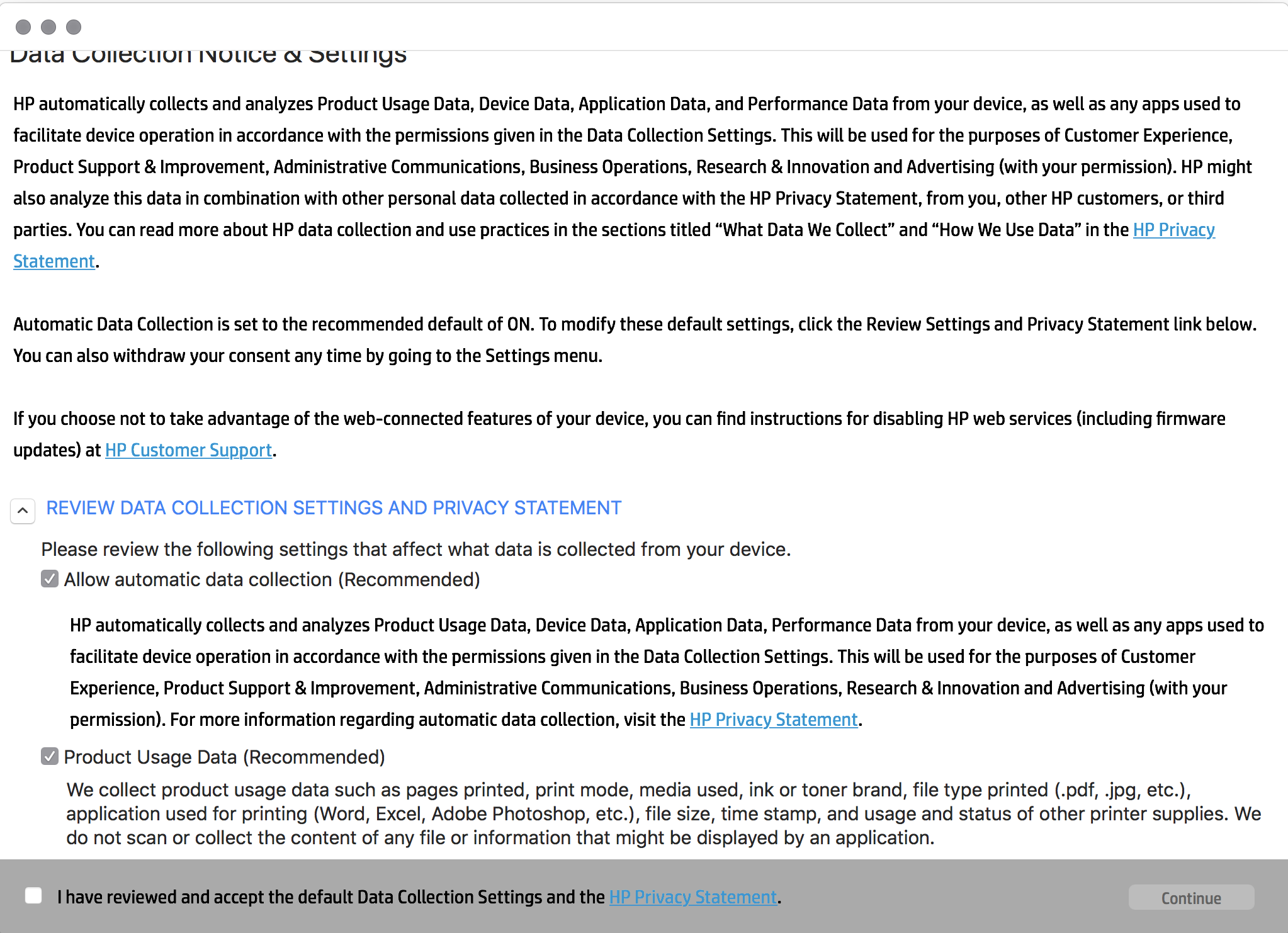

But it is only then, once the user has found the combination of “Next” and “Cancel” buttons that lead out of the swamp of hard sells and bad deals, that they are confronted with their biggest test: the “Data Collection Notice & Settings”.

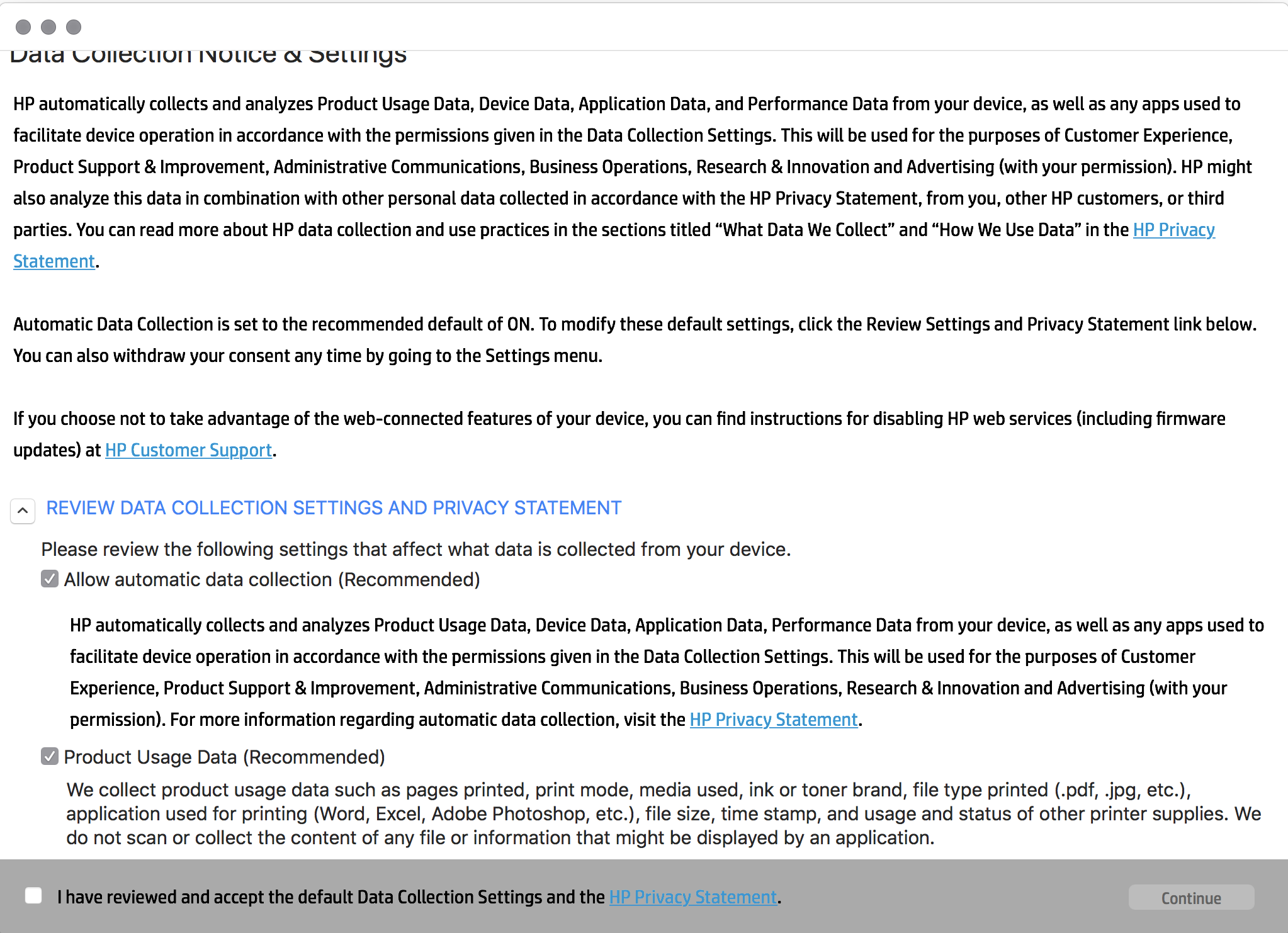

In summary, HP wants its printer to collect all kinds of data that a reasonable person would never expect it to. This includes metadata about your devices, as well as information about all the documents that you print, including timestamps, number of pages, and the application doing the printing (HP state that they do stop short of looking at the contents of your documents). From the HP privacy policy, linked to from the setup program:

Product Usage Data – We collect product usage data such as pages printed, print mode, media used, ink or toner brand, file type printed (.pdf, .jpg, etc.), application used for printing (Word, Excel, Adobe Photoshop, etc.), file size, time stamp, and usage and status of other printer supplies. We do not scan or collect the content of any file or information that might be displayed by an application.

Device Data – We collect information about your computer, printer and/or device such as operating system, firmware, amount of memory, region, language, time zone, model number, first start date, age of device, device manufacture date, browser version, device manufacturer, connection port, warranty status, unique device identifiers, advertising identifiers and additional technical information that varies by product.

HP wants to use the data they collect for a wide range of purposes, the most eyebrow-raising of which is for serving advertising. Note the last column in this “Privacy Matrix”, which states that “Product Usage Data” and “Device Data” (amongst many other types of data) are collected and shared with “service providers” for purposes of advertising.

HP delicately balances short-term profits with reasonable-man-ethics by only half-obscuring the checkboxes and language in this part of the setup.

At this point everything has become clear - the job of this setup app is not only to sell expensive ink subscriptions; it’s also to collect what apparently passes for informed consent in a court of law. I clicked the boxes to indicate “Jesus Christ no, obviously not, why would anyone ever knowingly consent to that”, and then spent 5 minutes Googling how to make sure that this setting was disabled. My research suggests that it’s controlled by an item in the settings menu of the printer itself labelled “Store anonymous usage information”. However, I don’t think any reasonable person would think that the meaning of “Store anonymous usage information” includes “send analytics data back to HP’s servers so that it can be used for targeted advertising”, so either HP is being deliberately coy or there’s another option that disables sending your data that I haven’t found yet.

I bet there’s also a vigorous debate to be had over whether HP’s definition of “anonymous” is the same as mine.

I imagine that a user’s data is exfiltrated back to HP by the printer itself, rather than any client-side software. Once HP has a user’s data then I don’t know what they do with it. Maybe if they can see that you are printing documents from Photoshop then they can send you spam for photo paper? I also don’t know anything about how much a user’s data is worth. My guess is that it’s depressingly little. I’d almost prefer it if HP was snatching highly valuable information that was worth making a high-risk, high-reward play for. But I can’t help but feel like they’re just grabbing whatever data is lying around because they might as well, it might be worth a few cents, and they (correctly) don’t anticipate any real risk to their reputation and bottom line from doing so.

Recommended for who?

I’m further unsure how a user’s printing data is connected back to the rest of their identity and used to power online advertising. It could be some combination of IP address, printer and computer MAC addresses, a serial number of some sort, or maybe just if the user gave HP their email address as part of setting up an expensive ink subscription. I pondered this question in some detail once I had set up my in-laws’ printer. I wanted to use the extremely convenient feature where the printer scans a document and sends it to you via email, but then I got scared that HP would purloin my email address, associate it with my printing data, and ship this information over to an online ad retargeting platform. I’m not a lawyer and I can’t be bothered to properly parse their privacy policy to understand whether this technically falls under “product usage” or “sharing with third-party services”, or whether I really did manage to tick and untick the right combination of boxes to make it clear that I don’t want them to do this. I especially can’t be bothered to have the debate over whether taking the hash of an email address suddenly makes it completely anonymous and harmless (it doesn’t).

When programmers write code, they also write “unit tests” in order to verify that the code works as expected. Whenever I find out about a grubby design decision made by a technology company, I always find it fun to muse about what the unit tests must look like.

# https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/24/nyregion/doordash-tip-policy.html

describe 'when a Doordash driver receives a tip' {

it 'keeps the extra money and does not give it to the driver' {

driver_pay_with_tip = calculate_pay(tip = 10)

driver_pay_without_tip = calculate_pay(tip = 0)

assert_equal(driver_pay_with_tip, driver_pay_without_tip)

}

}

describe 'when a user prints a document' {

it 'sends metadata on their activity back to HP servers' {

print_file()

assert(data_was_received())

}

}

To the people who are actually writing these unit tests: I know that we all accumulate status and pay rises and health insurance inside our companies that don’t always carry over into the rest of the world. I know that it can be hard to voice dissent, especially at decisions where the harm is nebulous and is only what everyone else is doing anyway. And I’m sure that it’s especially hard to reconcile conflicting emotions when you’re otherwise quite proud of the low-cost, reasonable-quality printers that your division churns out, spyware notwithstanding.

Actually it’s only now that I’ve started this bit that I realize I don’t have a punchline.

Where’s the harm in all this? I think it depends on what you care about and how much. I’m personally allergic to this kind of data-appropriation because I don’t believe I gain anything from it and the scummy tactics that try (and mostly succeed) to get my data just viscerally piss me off. But even if you would be perfectly happy to publish all your printing and device data to the entire internet, I’d still argue that it’s a grim world in which HP feels entitled to take it from you. And if nothing else, I believe that over ninety-nine percent of people whose printer sends their data to HP have no idea that this is happening, and would much prefer if it didn’t. This is not an exaggeration - I really do think that if you surveyed every single owner of every single spy-printer, ninety-nine out of every hundred would be unaware of the data collection and would want it to stop. If this claim is right then it would put the lie to any claim that this type of data-snagging is done with users’ knowing consent. I of course have no evidence for it, but it feels plausible, and since I’m not a journalist I don’t have to obey the Journalists’ Code. I can even invent the Journalists’ Code in the same sentence as I flout it.

Plus, I really don’t think that the onus should be on me to come up with watertight reasons why HP shouldn’t collect data on what people print in order to target them with online ads.

I don’t think that “is it OK if we have your printer collect metadata about your devices and what you print, and then use it online advertising?” is a question that HP should even be asking. They already know the answer, and all they’re really doing is giving people who have already paid them several hundred dollars for a cheap but functional printer the opportunity to make a mistake. Life is so much harder when you feel like you’re in a constant cold war standoff with your otherwise perfectly useful gadgets. The top of HP’s privacy policy page reads “HP recognizes that privacy is a fundamental human right and further recognizes the importance of privacy, security and data protection to our customers and partners worldwide.” Which just goes to show that you should probably ignore everything that a company says that doesn’t carry a specific and enforceable legal obligation.

If pressed then I would have to concede that HP have at least made it possible for a moderately informed and motivated user (i.e. me) to work out the gist of what they are hoping to do with my data. They’ve camouflaged, but (as far as I can tell) they haven’t lied, and I imagine that they’ve been careful not to do anything illegal. And at the end of the day, how else is a company meant to persuade users to part with data that they would never knowingly part with if they properly understood what was happening?

Last week my in-laws politely but firmly asked me to set up their new HP printer. I protested that I’m completely clueless about that sort of thing, despite my tax-return-job-title of “software engineer”. Still remonstrating, I was gently bundled into their study with an instruction pamphlet, a cup of tea, a promise to unlock the door once I’d printed everyone’s passport forms, and a warning not to try the window because the roof tiles are very loose.

At first the setup process was so simple that even a computer programmer could do it. But then, after I had finished removing pieces of cardboard and blue tape from the various drawers of the machine, I noticed that the final step required the downloading of an app of some sort onto a phone or computer. This set off my crapware detector.

It’s possible that I was being too cynical. I suppose that it was theoretically possible that the app could have been a thoughtfully-constructed wizard, which did nothing more than gently guide non-technical users through the sometimes-harrowing process of installing and testing printer drivers. It was at least conceivable that it could then quietly uninstall itself, satisfied with a simple job well done.

Of course, in reality it was a way to try and get people to sign up for expensive ink subscriptions and/or hand over their email addresses, plus something even more nefarious that we’ll talk about shortly (there were also some instructions for how to download a printer driver tacked onto the end). This was a shame, but not unexpected. I’m sure that the HP ink department is saddled with aggressive sales quotas, and no doubt the only way to hit them is to ruthlessly exploit people who don’t know that third-party cartridges are just as good as HP’s and are much cheaper. Fortunately, the careful user can still emerge unscathed from this phase of the setup process by gingerly navigating the UI patterns that presumably do fool some people who aren’t paying attention.

But it is only then, once the user has found the combination of “Next” and “Cancel” buttons that lead out of the swamp of hard sells and bad deals, that they are confronted with their biggest test: the “Data Collection Notice & Settings”.

In summary, HP wants its printer to collect all kinds of data that a reasonable person would never expect it to. This includes metadata about your devices, as well as information about all the documents that you print, including timestamps, number of pages, and the application doing the printing (HP state that they do stop short of looking at the contents of your documents). From the HP privacy policy, linked to from the setup program:

Product Usage Data – We collect product usage data such as pages printed, print mode, media used, ink or toner brand, file type printed (.pdf, .jpg, etc.), application used for printing (Word, Excel, Adobe Photoshop, etc.), file size, time stamp, and usage and status of other printer supplies. We do not scan or collect the content of any file or information that might be displayed by an application.

Device Data – We collect information about your computer, printer and/or device such as operating system, firmware, amount of memory, region, language, time zone, model number, first start date, age of device, device manufacture date, browser version, device manufacturer, connection port, warranty status, unique device identifiers, advertising identifiers and additional technical information that varies by product.

HP wants to use the data they collect for a wide range of purposes, the most eyebrow-raising of which is for serving advertising. Note the last column in this “Privacy Matrix”, which states that “Product Usage Data” and “Device Data” (amongst many other types of data) are collected and shared with “service providers” for purposes of advertising.

HP delicately balances short-term profits with reasonable-man-ethics by only half-obscuring the checkboxes and language in this part of the setup.

At this point everything has become clear - the job of this setup app is not only to sell expensive ink subscriptions; it’s also to collect what apparently passes for informed consent in a court of law. I clicked the boxes to indicate “Jesus Christ no, obviously not, why would anyone ever knowingly consent to that”, and then spent 5 minutes Googling how to make sure that this setting was disabled. My research suggests that it’s controlled by an item in the settings menu of the printer itself labelled “Store anonymous usage information”. However, I don’t think any reasonable person would think that the meaning of “Store anonymous usage information” includes “send analytics data back to HP’s servers so that it can be used for targeted advertising”, so either HP is being deliberately coy or there’s another option that disables sending your data that I haven’t found yet.

I bet there’s also a vigorous debate to be had over whether HP’s definition of “anonymous” is the same as mine.

I imagine that a user’s data is exfiltrated back to HP by the printer itself, rather than any client-side software. Once HP has a user’s data then I don’t know what they do with it. Maybe if they can see that you are printing documents from Photoshop then they can send you spam for photo paper? I also don’t know anything about how much a user’s data is worth. My guess is that it’s depressingly little. I’d almost prefer it if HP was snatching highly valuable information that was worth making a high-risk, high-reward play for. But I can’t help but feel like they’re just grabbing whatever data is lying around because they might as well, it might be worth a few cents, and they (correctly) don’t anticipate any real risk to their reputation and bottom line from doing so.

Recommended for who?

I’m further unsure how a user’s printing data is connected back to the rest of their identity and used to power online advertising. It could be some combination of IP address, printer and computer MAC addresses, a serial number of some sort, or maybe just if the user gave HP their email address as part of setting up an expensive ink subscription. I pondered this question in some detail once I had set up my in-laws’ printer. I wanted to use the extremely convenient feature where the printer scans a document and sends it to you via email, but then I got scared that HP would purloin my email address, associate it with my printing data, and ship this information over to an online ad retargeting platform. I’m not a lawyer and I can’t be bothered to properly parse their privacy policy to understand whether this technically falls under “product usage” or “sharing with third-party services”, or whether I really did manage to tick and untick the right combination of boxes to make it clear that I don’t want them to do this. I especially can’t be bothered to have the debate over whether taking the hash of an email address suddenly makes it completely anonymous and harmless (it doesn’t).

When programmers write code, they also write “unit tests” in order to verify that the code works as expected. Whenever I find out about a grubby design decision made by a technology company, I always find it fun to muse about what the unit tests must look like.

# https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/24/nyregion/doordash-tip-policy.html

describe 'when a Doordash driver receives a tip' {

it 'keeps the extra money and does not give it to the driver' {

driver_pay_with_tip = calculate_pay(tip = 10)

driver_pay_without_tip = calculate_pay(tip = 0)

assert_equal(driver_pay_with_tip, driver_pay_without_tip)

}

}

describe 'when a user prints a document' {

it 'sends metadata on their activity back to HP servers' {

print_file()

assert(data_was_received())

}

}

To the people who are actually writing these unit tests: I know that we all accumulate status and pay rises and health insurance inside our companies that don’t always carry over into the rest of the world. I know that it can be hard to voice dissent, especially at decisions where the harm is nebulous and is only what everyone else is doing anyway. And I’m sure that it’s especially hard to reconcile conflicting emotions when you’re otherwise quite proud of the low-cost, reasonable-quality printers that your division churns out, spyware notwithstanding.

Actually it’s only now that I’ve started this bit that I realize I don’t have a punchline.

Where’s the harm in all this? I think it depends on what you care about and how much. I’m personally allergic to this kind of data-appropriation because I don’t believe I gain anything from it and the scummy tactics that try (and mostly succeed) to get my data just viscerally piss me off. But even if you would be perfectly happy to publish all your printing and device data to the entire internet, I’d still argue that it’s a grim world in which HP feels entitled to take it from you. And if nothing else, I believe that over ninety-nine percent of people whose printer sends their data to HP have no idea that this is happening, and would much prefer if it didn’t. This is not an exaggeration - I really do think that if you surveyed every single owner of every single spy-printer, ninety-nine out of every hundred would be unaware of the data collection and would want it to stop. If this claim is right then it would put the lie to any claim that this type of data-snagging is done with users’ knowing consent. I of course have no evidence for it, but it feels plausible, and since I’m not a journalist I don’t have to obey the Journalists’ Code. I can even invent the Journalists’ Code in the same sentence as I flout it.

Plus, I really don’t think that the onus should be on me to come up with watertight reasons why HP shouldn’t collect data on what people print in order to target them with online ads.

I don’t think that “is it OK if we have your printer collect metadata about your devices and what you print, and then use it online advertising?” is a question that HP should even be asking. They already know the answer, and all they’re really doing is giving people who have already paid them several hundred dollars for a cheap but functional printer the opportunity to make a mistake. Life is so much harder when you feel like you’re in a constant cold war standoff with your otherwise perfectly useful gadgets. The top of HP’s privacy policy page reads “HP recognizes that privacy is a fundamental human right and further recognizes the importance of privacy, security and data protection to our customers and partners worldwide.” Which just goes to show that you should probably ignore everything that a company says that doesn’t carry a specific and enforceable legal obligation.

If pressed then I would have to concede that HP have at least made it possible for a moderately informed and motivated user (i.e. me) to work out the gist of what they are hoping to do with my data. They’ve camouflaged, but (as far as I can tell) they haven’t lied, and I imagine that they’ve been careful not to do anything illegal. And at the end of the day, how else is a company meant to persuade users to part with data that they would never knowingly part with if they properly understood what was happening?