How to win friends and influence repos

21 Jul 2014

In my last post, I wrote about the breathless highs I experienced whilst discovering productivity systems for the first time, and the subsequent crushing lows of realising that I was just another prick with a Dymo labeller. I also alluded to an ingenious framework that I have been evolving over the last year, which is obviously totally different to all the moonshine systems those snake oil organisational gurus are peddling. Therefore, with a staggering lack of self-awareness, I present to you a moderately detailed, frequently myopic, but hopefully nonetheless quite interesting description of how I roll at work. It goes without saying that this is largely a patchwork plagiarism of many unattributed sources, but there’s a fair few original twists in there too.

0. How to win friends and influence repos

I’m a software engineer, and so that’s what this system is optimised for.

It requires very little discipline after the initial breaking-in period, because everything in it either produces immediate benefit or fills a spreadsheet with pretty colours. And as my pappy always says, it doesn’t take much force of will to have lunch everyday. Whilst it seems like a lot when written down, it feels very lightweight to me. It adds very little overhead, is mostly centred around bringing structure to things you already do, and I want to say that everything is there for a reason. But then again, I would say that.

1. Broad structure

- Setup - at the start of each day, read your emails, plan your day on a Sticky, learn something new and run through your Anki flashcard deck

- Doing work - work in 45 min sprints, and record them on today’s Sticky

- Capturing information - capture questions in Omnifocus, answers in Anki, and company-specific information in Notational Velocity

- Sending emails - when programming, ignore your emails. Every 45 mins, send urgent, time sensitive emails. Batch non-urgent emails at the end of the day

- End of the day - fill in a brief spreadsheet

2. Tools

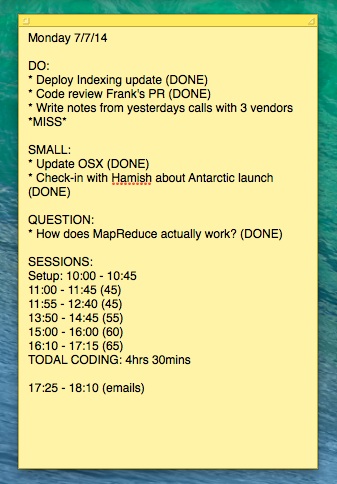

2.1 Stickies

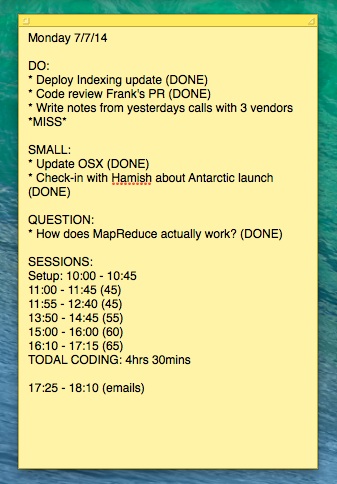

The default OSX Stickies application is at the front and centre of each and every day. In the morning, read all your emails (more on this later) and then fill out a Sticky with the following fields:

2.1.1 DO

The 2-3 concrete, specific, fail-able things you want to do today. Don’t be vague. “Work on OplogTailer” is vague and impossible to fail or succeed at. “Finish skeleton architecture and tests for OplogTailer” is much better. “Email more customers” is vague. “Email 10 customers and respond to the 4 who replied yesterday” is great. This kind of language gives you actual goalposts to aim at, rather than aimlessly booting a ball around a park. Break these headlines into lists of sub-tasks if that is useful. Mark things with (DONE) when you finish them.

2.1.2 SMALL

The N little things that you need to do today but won’t define whether or not today is a good day. “Read Steve’s report”, “Ask Barry whether he is around on Monday” and “Install SilverSearcher” all belong here.

2.1.3 QUESTION

Pick one question from your Omnifocus list of questions (see below) and find out the answer during your Setup. Put the answer in Anki (see below). “What is the actual difference between JSONP and CORS?”, “What’s the deal with PGP?” and “How do buffers work in vim?” are good examples.

2.1.4 SESSIONS

My favourite section, used to keep track of how much programming you get to do during a day. When you start programming, put on your headphones, press start on your timer and write down the time. When your timer goes off, find a convenient place to stop, write down the time and take your headphones off. Check your emails and anything else you fancy. Walk around a bit. 5-15 mins later (depending on how you feel and how nice it is outside), rinse and repeat. If you work to the clock, in X minute sprints and in an environment that allows you to focus, this quickly becomes surprisingly frictionless. At the end of the day, add up the time you spent programming. For me it’s usually around 4 hours. I don’t think I have ever had more than 6.

Used in the right spirit, this is a powerful tool for happiness.

- It conditions you to work in focussed sprints. This is like oxygen, in that you don’t need to know why it is beneficial in order for it to help you.

- It helps you identify if you keep getting interrupted and aren’t getting blocks of time in which to programme. You can then work out how to fix this.

- It helps you realise that you are working hard enough, and that writing code just takes a long time. If you are consistently writing around 4 hours of concentrated code everyday, whilst staying on top of your emails, helping other people with their problems and building relationships with those around you, then there is nothing you need to worry about.

Stickies bring tangible form and character to your days. During your Setup you can see whether today is going to be a chopped up day of calls, meetings and interviews, or whether you can mostly forget about the outside world and focus on your terminal. If you find yourself furiously shaving yaks inside a mile-long rabbit hole, you can immediately see where you actually wanted to be at the start of your day and haul yourself back above ground.

However, there are dangers. It’s important not to make each day a localised competition to make your total time spent coding as high as possible. You want to identify general trends that you can improve upon, not monitor your day-on-day performance. 5 minutes of extra work is not going to make any qualitative difference to anything, and if you find yourself cutting breaks short because you want to steal a march on yourself from last week then you’re doing it wrong. Don’t exaggerate or tell yourself that the time you spent writing those emails should probably go in here. Just record the way things go, trust that you are doing well and see if you can use what you discover to make things easier for yourself.

2.1.5 Each week

On Monday morning, before making your Sticky for the coming day, make a note in Evernote called “$YOUR_COMPANY WB $LAST_MONDAYS_DATE”. Copy last week’s Stickies into this note and then delete them. Have a quick look over them, and write a 5-line summary of how your week went and what you did. The results will often be illuminating, and the process helps bring shape to your weeks in the same way that the individual Stickies bring it to your days. Having a better picture of your high-level history makes it easier to see your overall thread, roughly how long things take in calendar time, and what the hell you actually spend your days doing.

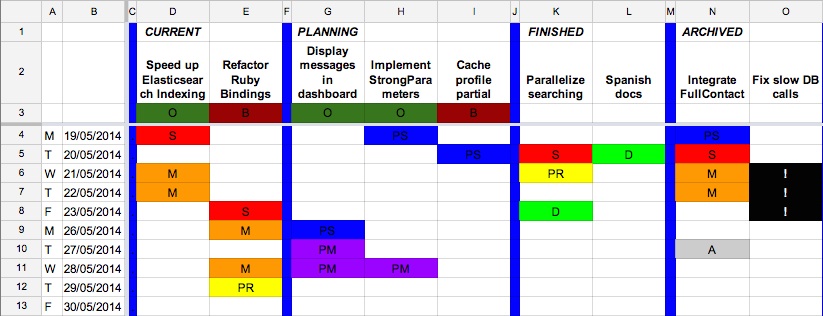

2.2 The Spreadsheet Of Truth

Even in the best of dev teams, you will sometimes get blocked. Maybe you are waiting on code review, or on confirmation of specs, or on an external vendor. If the team is big, and especially if you are remote, this can happen more than you would like.

Getting unblocked is often a much less satisfying process than writing code. When projects start to require input other than more and better LOC, I often find myself feeling restless and under-utilised. The most pleasant solution is to grab another issue, git checkout -b rob-new-feature-4723, and get back to mashing my keyboard. But this leaves a lot of balls in the air and thousands of dollars of invisible Work In Progress code inventory lying around. It makes it difficult to hard-switch your entire focus to an emerging problem because you have to keep track of so much WIP that you vaguely know you need to deploy sometime soon.

Your cycle time (the time taken for a feature to go from idea to deployment) is typically more important to your overall success than aggregate throughput and capacity. It is generally better to complete 3 projects that each take 2 weeks one after the other, rather than complete 4 projects in parallel that are all deployed at the end of 6 weeks. The most intuitive explanation is that the quicker something gets into production, the quicker you can start learning from it, and that this can easily trump all other considerations. Donald Reinertsen’s Product Development Flow has 300 pages of pure rigour on this and many other topics.

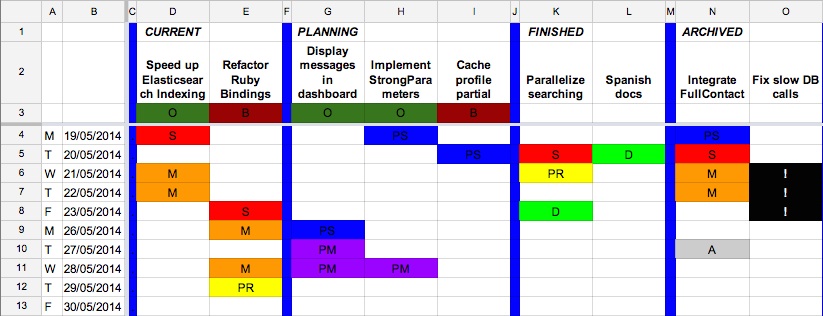

To make my invisible WIP show itself, to get some concrete idea of my typical cycle times, and to be able to say definitively all the things I am currently committed to work on, I made a colourful Google Docs spreadsheet (The Spreadsheet Of Truth).

Each column is a project, and should usually map to a single pull request, for example “Speed up Elasticsearch indexing” or “Refactor Ruby bindings”. At the top of each Preparing and Coding project column, put an O for Open, or a B for Blocked. There are then 4 larger groups of columns:

- Planning - you have started establishing specs, talking to external partners, and all the other things you do that don’t involve writing code

- Current - you have started coding

- Finished - you have finished the project!

- Archived - you started work on the project in some form, but now it is paused or dead

This allows you to see the things in your immediate queue and to notice when this gets too large. 3 projects in Current is almost always too many, and 3 in Planning might just about be OK if some of them are still very high-level and long-term. You can see which projects you are blocked on and are forced to consider that perhaps you should work on becoming unblocked rather than starting yet another concurrent project. It shows you all of the things you have ever done at a company, which might be collecting data for data’s sake, but is still pretty cool. However, as is so often the case, the real magic comes when you add coloured squares:

- SP - the day it was decided that you would be taking a project

- MP - any day where you spend a significant amount of time (>30 mins) preparing a project

- S - the day you first wrote code on a project

- M - any subsequent day where you wrote code on a project

- PR - you made a Pull Request!

- D - you deployed the project!

- A - the project was archived/killed

- ! - a bug/breakage that took time to work on but you couldn’t resolve

Some days may fit into multiple categories (eg. you start and make a PR on the same day); just choose whatever category feels most useful, this isn’t meant to be rigorous, quantitative data. As you get onto larger and more complicated projects this system may break down, but I suspect that if this happens then the project could probably benefit from being simplified or broken up into chunks that do fit this taxonomy.

And that’s it. It takes approximately 15 seconds to fill in and is a pleasant way to bookend a day at work and officially declare it over. It requires discipline at first, but then once you see patterns emerging (both in the data and pretty colours sense) and are able to make adjustments based on them, it becomes a really rather exciting activity (no I do not need more hobbies). So far I have found:

- That I accept too many new projects into Preparing too easily, without thinking about their overhead and my current backlog

- That I let projects sit in a PR state for too long, and need to be more focussed on getting review done and removing blockers to deployment

- That having a large queue in Preparing makes it hard to fast-track anything. There can easily be several weeks between a project being assigned to me and me writing any code on it. This is sometimes due to communication drag, but I think a lot of it comes from a lack of urgency, since it is just one more project amongst 4 or 5 coming up.

- That I need to get more confident about deploying. Waiting until someone is around to hold my hand can introduce delays of several days or more between a PR being given the all clear and the code hitting production.

And this is only from the last few months.

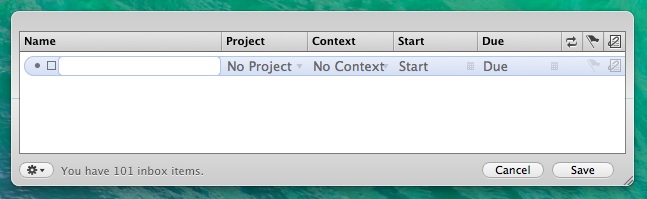

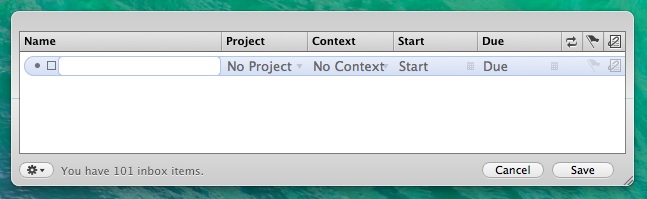

2.3 Omnifocus

Omnifocus allows you to press a global shortcut (default Ctrl+Cmd+Space) and make a note from anywhere. This is worth the $40 pricetag on its own. It makes capturing small to-dos, vague ideas and inspiring quotes entirely effortless. The rest of the product is built around a classical GTD system, but I just have one list of Misc to-dos and mostly use it as a place to dump things I think of that don’t belong anywhere else. The most important lists I have are:

- Questions - mostly technical questions that you would like to know the answer to. Pick one/day to put on your Sticky (see above), and answer it in Anki (see below).

- Wishlist - product ideas you would like to implement one day, but aren’t yet mature or important enough to put in the team’s backlog.

- Compost - tidbits of wisdom that you think of, read or hear. You will very rarely read them again, but will still feel like you are at least not losing them (even though for all intents and purposes you are).

Context-agnostic note-taking really is a special thing.

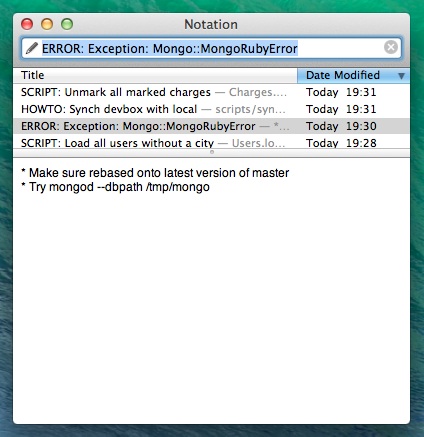

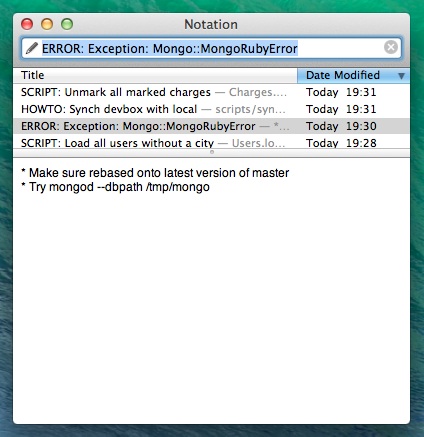

2.4 Notational Velocity

Notational Velocity is perfect for storing all the company-specific incantations and solutions for common error messages that you otherwise have to ask co-workers or Google for over and over again. It’s essentially Evernote optimised for storing and retrieving pointed snippets of information. It’s incredibly simple, lightning fast and stuffed with every keyboard shortcut you could ever desire. I’ve found it particularly useful for storing ad-hoc scripts that I run in a console, e.g. “Create and refund 10 test charges” or “Set every user’s country to be Germany”. You’d be surprised how often these have reuse value and how much more frequently you write sensible scripts if you know you are permanently expanding your arsenal of commands. For the sake of stack-size control I also write longer documents like test plans and architecture designs in it, although I suspect that this is not the optimum place for them.

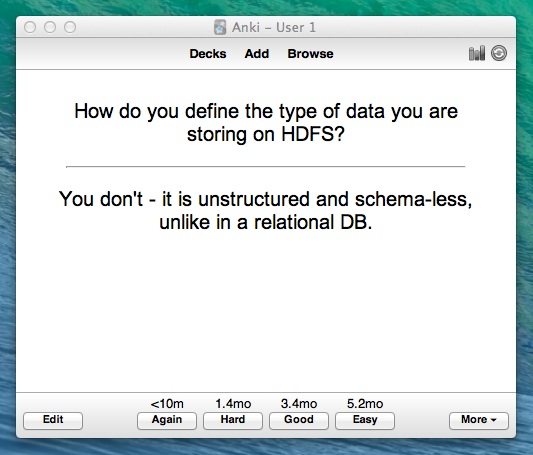

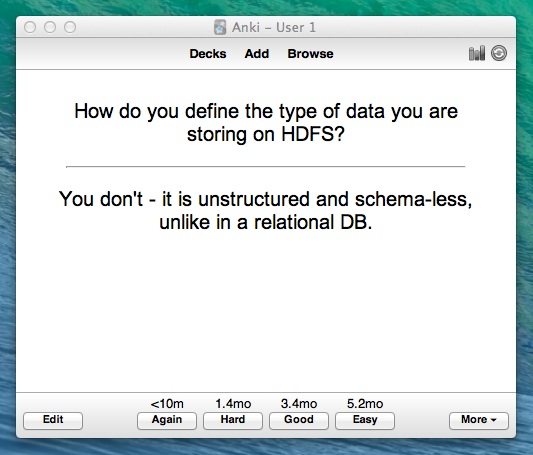

2.5 Anki

Anki is Q&A flashcards done very simply and very well. I’ve wanted to use it properly for several years, but have never been able to make the habit stick. However, now that it has become part of my morning Setup and I am systematically learning at least one definable new thing every day, it has finally stuck. As you start to remember more stuff, and can see an ever-expanding list of all the new things you now know, you spark off a virtuous circle of wanting to learn and capture even more things.

It is particularly suited for learning things like Unix commands, vim syntax and OSX shortcuts. Whilst learning new Unix commands materially increases the amount of stuff you are able to, getting better at vim and OSX just makes you a little bit faster at doing the same stuff you were doing before. This is cool, but I would suggest that after a while they become another form of code golf, and are mostly ways to save wear and tear on your mouse hand rather than make any qualitative difference to your output and abilities. Which is fine, but seems worth recognising (more on this below).

As mentioned above, blitz through your deck during your morning Setup each day and then spend 5-10 minutes learning something new and converting what you learn into flashcard form. Whenever you learn something new during the day, turn it into a card. This will reduce the amount of time you spend on the Ruby#Array documentation by 90%.

3. Inbox zero

At the end of each day, I am always (always) at inbox zero. But I guess that this is quite easy, since I don’t really get that many emails. Unsubscribe to everything you can, and try and ensure that the only messages that make it into your main inbox are those that were written by a human and are addressed specifically to you. Filter and archive emails from Github, Sentry, Tddium etc. onto their own separate labels, without marking them as read. This effectively gives you different inboxes with different characteristics and levels of priority. It allows you to batch-read each type of email, rather than jumping between them. Use an @Action label to mark the emails you actually need to reply to, and blitz through them once/day (or thereabouts).

In general, do read your emails at the start of the working day. Much is made of the holiness of the morning and how this is a terrible idea that will destroy your entire day, but this assumes that you are spending most of your days being buffeted by the winds of your inbox, and need to carve out morsels of time to think and focus. However, if you are an engineer who doesn’t get to spend big chunks of the day focussing and programming already, you have systemic problems that need solving at the root. As long as you don’t answer these emails, you trade ~15 minutes (that you will have to spend at some point anyway) in return for being totally up to date when writing your daily Sticky. You know in advance if there are any emergent curveballs that you will need to take a look at, and can make immediate course-corrections on the main work you are doing.

4. Principles

Despite having just taken several thousand words to describe how I organise myself, I still believe that this is all driven by simplicity. I try and add features only when I feel a burning need or sense a particularly interesting experiment. On the other, I would have said this 2 years ago when I was systematically making everything around me as complicated as possible as well, so you probably can’t trust anything I say too much.

I generally find Quantified Self to be a little strange and unnerving. In theory, finding out about yourself and optimising based on what you learn sounds great. But at some point you have to believe that the measurement overhead and cognitive space taken up by the process and analysis starts to detract significantly from the life that you are trying to optimise. On the other hand, there are some things where I feel you have a straight choice between keeping basic tabs on what you do, or just being a bit worse at it than you could be. My arbitrary line in the sand is pretty much the system above.

I do use RescueTime to see how much time I spend doing various things each week, but for qualitative purposes like checking that my crippling pornography addiction is broadly under control n.b. I do not actually have a crippling pornography addiction. What gets measured gets optimised, and when you start trying to nudge that % productivity score up a few points each week, you are again probably moving towards an unpleasantly obsessive place. But seeing that your time spent IM-ing has been steadily going up for the past year can only be interesting and relevant.

Doing pseudo-productive stuff for fun is fine, but be honest that that’s what it is. Reading more that a Hacker Newsletter’s-worth of blog posts per week can be a very pleasant way to spend your time, but quickly starts to go well beyond what you need to do in order to “keep abreast of the industry”. The same applies to listening to podcasts, reading books and watching talks. If you don’t write notes afterwards and spend a non-negligible amount of time reflecting on what you have heard, you will forget it very quickly. You might retain a few nuggets here and there, but not enough to justify the amount of time you invested into consuming it. That’s fine - listening and reading and watching can all be great fun and therefore time well spent by default, but if you aren’t honest that you really are doing these things for enjoyment then you can easily mislead yourself about how much you are learning. Even worse, it can become harder to do fun things that don’t have an alluring veneer of productivity wrapped around them.

If and when you have to spend a significant amount of time on things other than writing code, parts of this system do start to break down. The difference between maker’s schedule and manager’s schedule has become something of a cliche by now, but that doesn’t mean it’s not still right. I do feel, however, that the dichotomy is too often seen as maker’s schedule and dickhead’s schedule, which is a total misunderstanding of pretty much everything. But it is true that when managing and organising people rather than pointers you can’t think in the broad strokes you’re used to, and the metrics you normally use to define A Good Day don’t really apply anymore. I’ll let you know when I’ve figured out how to deal with this.

5. Conclusion

In my previous post, I was pretty hard on my old self and his approach to organisation. And for good reason. That guy was OK, but had some pretty crazy delusions of grandeur and was just desperate to feel busier and more important than he actually was. On the other hand, you do just have to try things and see what sticks. It’s only arrogant douchebaggery if it doesn’t work, otherwise it’s just being smart. As I wrote before, if you’re going to do something then you might as well do it right. A degree of structure, developed over time in response to needs that you actually feel, has to be a sensible thing. Just be careful when some doofus starts trying to force-feed you his goofy system.

Appendix

- Public Spreadsheet Of Truth example - GoogleDocs

- Omnifocus - https://www.omnigroup.com/omnifocus

- Notational Velocity - http://notational.net/

- Evernote - https://evernote.com/

- Anki - http://ankisrs.net/, my deck is public at https://ankiweb.net/shared/info/566886200

- RescueTime - https://www.rescuetime.com/

- Minutes Timer - https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/minutes/id406827163?mt=12

In my last post, I wrote about the breathless highs I experienced whilst discovering productivity systems for the first time, and the subsequent crushing lows of realising that I was just another prick with a Dymo labeller. I also alluded to an ingenious framework that I have been evolving over the last year, which is obviously totally different to all the moonshine systems those snake oil organisational gurus are peddling. Therefore, with a staggering lack of self-awareness, I present to you a moderately detailed, frequently myopic, but hopefully nonetheless quite interesting description of how I roll at work. It goes without saying that this is largely a patchwork plagiarism of many unattributed sources, but there’s a fair few original twists in there too.

0. How to win friends and influence repos

I’m a software engineer, and so that’s what this system is optimised for.

It requires very little discipline after the initial breaking-in period, because everything in it either produces immediate benefit or fills a spreadsheet with pretty colours. And as my pappy always says, it doesn’t take much force of will to have lunch everyday. Whilst it seems like a lot when written down, it feels very lightweight to me. It adds very little overhead, is mostly centred around bringing structure to things you already do, and I want to say that everything is there for a reason. But then again, I would say that.

1. Broad structure

- Setup - at the start of each day, read your emails, plan your day on a Sticky, learn something new and run through your Anki flashcard deck

- Doing work - work in 45 min sprints, and record them on today’s Sticky

- Capturing information - capture questions in Omnifocus, answers in Anki, and company-specific information in Notational Velocity

- Sending emails - when programming, ignore your emails. Every 45 mins, send urgent, time sensitive emails. Batch non-urgent emails at the end of the day

- End of the day - fill in a brief spreadsheet

2. Tools

2.1 Stickies

The default OSX Stickies application is at the front and centre of each and every day. In the morning, read all your emails (more on this later) and then fill out a Sticky with the following fields:

2.1.1 DO

The 2-3 concrete, specific, fail-able things you want to do today. Don’t be vague. “Work on OplogTailer” is vague and impossible to fail or succeed at. “Finish skeleton architecture and tests for OplogTailer” is much better. “Email more customers” is vague. “Email 10 customers and respond to the 4 who replied yesterday” is great. This kind of language gives you actual goalposts to aim at, rather than aimlessly booting a ball around a park. Break these headlines into lists of sub-tasks if that is useful. Mark things with (DONE) when you finish them.

2.1.2 SMALL

The N little things that you need to do today but won’t define whether or not today is a good day. “Read Steve’s report”, “Ask Barry whether he is around on Monday” and “Install SilverSearcher” all belong here.

2.1.3 QUESTION

Pick one question from your Omnifocus list of questions (see below) and find out the answer during your Setup. Put the answer in Anki (see below). “What is the actual difference between JSONP and CORS?”, “What’s the deal with PGP?” and “How do buffers work in vim?” are good examples.

2.1.4 SESSIONS

My favourite section, used to keep track of how much programming you get to do during a day. When you start programming, put on your headphones, press start on your timer and write down the time. When your timer goes off, find a convenient place to stop, write down the time and take your headphones off. Check your emails and anything else you fancy. Walk around a bit. 5-15 mins later (depending on how you feel and how nice it is outside), rinse and repeat. If you work to the clock, in X minute sprints and in an environment that allows you to focus, this quickly becomes surprisingly frictionless. At the end of the day, add up the time you spent programming. For me it’s usually around 4 hours. I don’t think I have ever had more than 6.

Used in the right spirit, this is a powerful tool for happiness.

- It conditions you to work in focussed sprints. This is like oxygen, in that you don’t need to know why it is beneficial in order for it to help you.

- It helps you identify if you keep getting interrupted and aren’t getting blocks of time in which to programme. You can then work out how to fix this.

- It helps you realise that you are working hard enough, and that writing code just takes a long time. If you are consistently writing around 4 hours of concentrated code everyday, whilst staying on top of your emails, helping other people with their problems and building relationships with those around you, then there is nothing you need to worry about.

Stickies bring tangible form and character to your days. During your Setup you can see whether today is going to be a chopped up day of calls, meetings and interviews, or whether you can mostly forget about the outside world and focus on your terminal. If you find yourself furiously shaving yaks inside a mile-long rabbit hole, you can immediately see where you actually wanted to be at the start of your day and haul yourself back above ground.

However, there are dangers. It’s important not to make each day a localised competition to make your total time spent coding as high as possible. You want to identify general trends that you can improve upon, not monitor your day-on-day performance. 5 minutes of extra work is not going to make any qualitative difference to anything, and if you find yourself cutting breaks short because you want to steal a march on yourself from last week then you’re doing it wrong. Don’t exaggerate or tell yourself that the time you spent writing those emails should probably go in here. Just record the way things go, trust that you are doing well and see if you can use what you discover to make things easier for yourself.

2.1.5 Each week

On Monday morning, before making your Sticky for the coming day, make a note in Evernote called “$YOUR_COMPANY WB $LAST_MONDAYS_DATE”. Copy last week’s Stickies into this note and then delete them. Have a quick look over them, and write a 5-line summary of how your week went and what you did. The results will often be illuminating, and the process helps bring shape to your weeks in the same way that the individual Stickies bring it to your days. Having a better picture of your high-level history makes it easier to see your overall thread, roughly how long things take in calendar time, and what the hell you actually spend your days doing.

2.2 The Spreadsheet Of Truth

Even in the best of dev teams, you will sometimes get blocked. Maybe you are waiting on code review, or on confirmation of specs, or on an external vendor. If the team is big, and especially if you are remote, this can happen more than you would like.

Getting unblocked is often a much less satisfying process than writing code. When projects start to require input other than more and better LOC, I often find myself feeling restless and under-utilised. The most pleasant solution is to grab another issue, git checkout -b rob-new-feature-4723, and get back to mashing my keyboard. But this leaves a lot of balls in the air and thousands of dollars of invisible Work In Progress code inventory lying around. It makes it difficult to hard-switch your entire focus to an emerging problem because you have to keep track of so much WIP that you vaguely know you need to deploy sometime soon.

Your cycle time (the time taken for a feature to go from idea to deployment) is typically more important to your overall success than aggregate throughput and capacity. It is generally better to complete 3 projects that each take 2 weeks one after the other, rather than complete 4 projects in parallel that are all deployed at the end of 6 weeks. The most intuitive explanation is that the quicker something gets into production, the quicker you can start learning from it, and that this can easily trump all other considerations. Donald Reinertsen’s Product Development Flow has 300 pages of pure rigour on this and many other topics.

To make my invisible WIP show itself, to get some concrete idea of my typical cycle times, and to be able to say definitively all the things I am currently committed to work on, I made a colourful Google Docs spreadsheet (The Spreadsheet Of Truth).

Each column is a project, and should usually map to a single pull request, for example “Speed up Elasticsearch indexing” or “Refactor Ruby bindings”. At the top of each Preparing and Coding project column, put an O for Open, or a B for Blocked. There are then 4 larger groups of columns:

- Planning - you have started establishing specs, talking to external partners, and all the other things you do that don’t involve writing code

- Current - you have started coding

- Finished - you have finished the project!

- Archived - you started work on the project in some form, but now it is paused or dead

This allows you to see the things in your immediate queue and to notice when this gets too large. 3 projects in Current is almost always too many, and 3 in Planning might just about be OK if some of them are still very high-level and long-term. You can see which projects you are blocked on and are forced to consider that perhaps you should work on becoming unblocked rather than starting yet another concurrent project. It shows you all of the things you have ever done at a company, which might be collecting data for data’s sake, but is still pretty cool. However, as is so often the case, the real magic comes when you add coloured squares:

- SP - the day it was decided that you would be taking a project

- MP - any day where you spend a significant amount of time (>30 mins) preparing a project

- S - the day you first wrote code on a project

- M - any subsequent day where you wrote code on a project

- PR - you made a Pull Request!

- D - you deployed the project!

- A - the project was archived/killed

- ! - a bug/breakage that took time to work on but you couldn’t resolve

Some days may fit into multiple categories (eg. you start and make a PR on the same day); just choose whatever category feels most useful, this isn’t meant to be rigorous, quantitative data. As you get onto larger and more complicated projects this system may break down, but I suspect that if this happens then the project could probably benefit from being simplified or broken up into chunks that do fit this taxonomy.

And that’s it. It takes approximately 15 seconds to fill in and is a pleasant way to bookend a day at work and officially declare it over. It requires discipline at first, but then once you see patterns emerging (both in the data and pretty colours sense) and are able to make adjustments based on them, it becomes a really rather exciting activity (no I do not need more hobbies). So far I have found:

- That I accept too many new projects into Preparing too easily, without thinking about their overhead and my current backlog

- That I let projects sit in a PR state for too long, and need to be more focussed on getting review done and removing blockers to deployment

- That having a large queue in Preparing makes it hard to fast-track anything. There can easily be several weeks between a project being assigned to me and me writing any code on it. This is sometimes due to communication drag, but I think a lot of it comes from a lack of urgency, since it is just one more project amongst 4 or 5 coming up.

- That I need to get more confident about deploying. Waiting until someone is around to hold my hand can introduce delays of several days or more between a PR being given the all clear and the code hitting production.

And this is only from the last few months.

2.3 Omnifocus

Omnifocus allows you to press a global shortcut (default Ctrl+Cmd+Space) and make a note from anywhere. This is worth the $40 pricetag on its own. It makes capturing small to-dos, vague ideas and inspiring quotes entirely effortless. The rest of the product is built around a classical GTD system, but I just have one list of Misc to-dos and mostly use it as a place to dump things I think of that don’t belong anywhere else. The most important lists I have are:

- Questions - mostly technical questions that you would like to know the answer to. Pick one/day to put on your Sticky (see above), and answer it in Anki (see below).

- Wishlist - product ideas you would like to implement one day, but aren’t yet mature or important enough to put in the team’s backlog.

- Compost - tidbits of wisdom that you think of, read or hear. You will very rarely read them again, but will still feel like you are at least not losing them (even though for all intents and purposes you are).

Context-agnostic note-taking really is a special thing.

2.4 Notational Velocity

Notational Velocity is perfect for storing all the company-specific incantations and solutions for common error messages that you otherwise have to ask co-workers or Google for over and over again. It’s essentially Evernote optimised for storing and retrieving pointed snippets of information. It’s incredibly simple, lightning fast and stuffed with every keyboard shortcut you could ever desire. I’ve found it particularly useful for storing ad-hoc scripts that I run in a console, e.g. “Create and refund 10 test charges” or “Set every user’s country to be Germany”. You’d be surprised how often these have reuse value and how much more frequently you write sensible scripts if you know you are permanently expanding your arsenal of commands. For the sake of stack-size control I also write longer documents like test plans and architecture designs in it, although I suspect that this is not the optimum place for them.

2.5 Anki

Anki is Q&A flashcards done very simply and very well. I’ve wanted to use it properly for several years, but have never been able to make the habit stick. However, now that it has become part of my morning Setup and I am systematically learning at least one definable new thing every day, it has finally stuck. As you start to remember more stuff, and can see an ever-expanding list of all the new things you now know, you spark off a virtuous circle of wanting to learn and capture even more things.

It is particularly suited for learning things like Unix commands, vim syntax and OSX shortcuts. Whilst learning new Unix commands materially increases the amount of stuff you are able to, getting better at vim and OSX just makes you a little bit faster at doing the same stuff you were doing before. This is cool, but I would suggest that after a while they become another form of code golf, and are mostly ways to save wear and tear on your mouse hand rather than make any qualitative difference to your output and abilities. Which is fine, but seems worth recognising (more on this below).

As mentioned above, blitz through your deck during your morning Setup each day and then spend 5-10 minutes learning something new and converting what you learn into flashcard form. Whenever you learn something new during the day, turn it into a card. This will reduce the amount of time you spend on the Ruby#Array documentation by 90%.

3. Inbox zero

At the end of each day, I am always (always) at inbox zero. But I guess that this is quite easy, since I don’t really get that many emails. Unsubscribe to everything you can, and try and ensure that the only messages that make it into your main inbox are those that were written by a human and are addressed specifically to you. Filter and archive emails from Github, Sentry, Tddium etc. onto their own separate labels, without marking them as read. This effectively gives you different inboxes with different characteristics and levels of priority. It allows you to batch-read each type of email, rather than jumping between them. Use an @Action label to mark the emails you actually need to reply to, and blitz through them once/day (or thereabouts).

In general, do read your emails at the start of the working day. Much is made of the holiness of the morning and how this is a terrible idea that will destroy your entire day, but this assumes that you are spending most of your days being buffeted by the winds of your inbox, and need to carve out morsels of time to think and focus. However, if you are an engineer who doesn’t get to spend big chunks of the day focussing and programming already, you have systemic problems that need solving at the root. As long as you don’t answer these emails, you trade ~15 minutes (that you will have to spend at some point anyway) in return for being totally up to date when writing your daily Sticky. You know in advance if there are any emergent curveballs that you will need to take a look at, and can make immediate course-corrections on the main work you are doing.

4. Principles

Despite having just taken several thousand words to describe how I organise myself, I still believe that this is all driven by simplicity. I try and add features only when I feel a burning need or sense a particularly interesting experiment. On the other, I would have said this 2 years ago when I was systematically making everything around me as complicated as possible as well, so you probably can’t trust anything I say too much.

I generally find Quantified Self to be a little strange and unnerving. In theory, finding out about yourself and optimising based on what you learn sounds great. But at some point you have to believe that the measurement overhead and cognitive space taken up by the process and analysis starts to detract significantly from the life that you are trying to optimise. On the other hand, there are some things where I feel you have a straight choice between keeping basic tabs on what you do, or just being a bit worse at it than you could be. My arbitrary line in the sand is pretty much the system above.

I do use RescueTime to see how much time I spend doing various things each week, but for qualitative purposes like checking that my crippling pornography addiction is broadly under control n.b. I do not actually have a crippling pornography addiction. What gets measured gets optimised, and when you start trying to nudge that % productivity score up a few points each week, you are again probably moving towards an unpleasantly obsessive place. But seeing that your time spent IM-ing has been steadily going up for the past year can only be interesting and relevant.

Doing pseudo-productive stuff for fun is fine, but be honest that that’s what it is. Reading more that a Hacker Newsletter’s-worth of blog posts per week can be a very pleasant way to spend your time, but quickly starts to go well beyond what you need to do in order to “keep abreast of the industry”. The same applies to listening to podcasts, reading books and watching talks. If you don’t write notes afterwards and spend a non-negligible amount of time reflecting on what you have heard, you will forget it very quickly. You might retain a few nuggets here and there, but not enough to justify the amount of time you invested into consuming it. That’s fine - listening and reading and watching can all be great fun and therefore time well spent by default, but if you aren’t honest that you really are doing these things for enjoyment then you can easily mislead yourself about how much you are learning. Even worse, it can become harder to do fun things that don’t have an alluring veneer of productivity wrapped around them.

If and when you have to spend a significant amount of time on things other than writing code, parts of this system do start to break down. The difference between maker’s schedule and manager’s schedule has become something of a cliche by now, but that doesn’t mean it’s not still right. I do feel, however, that the dichotomy is too often seen as maker’s schedule and dickhead’s schedule, which is a total misunderstanding of pretty much everything. But it is true that when managing and organising people rather than pointers you can’t think in the broad strokes you’re used to, and the metrics you normally use to define A Good Day don’t really apply anymore. I’ll let you know when I’ve figured out how to deal with this.

5. Conclusion

In my previous post, I was pretty hard on my old self and his approach to organisation. And for good reason. That guy was OK, but had some pretty crazy delusions of grandeur and was just desperate to feel busier and more important than he actually was. On the other hand, you do just have to try things and see what sticks. It’s only arrogant douchebaggery if it doesn’t work, otherwise it’s just being smart. As I wrote before, if you’re going to do something then you might as well do it right. A degree of structure, developed over time in response to needs that you actually feel, has to be a sensible thing. Just be careful when some doofus starts trying to force-feed you his goofy system.

Appendix

- Public Spreadsheet Of Truth example - GoogleDocs

- Omnifocus - https://www.omnigroup.com/omnifocus

- Notational Velocity - http://notational.net/

- Evernote - https://evernote.com/

- Anki - http://ankisrs.net/, my deck is public at https://ankiweb.net/shared/info/566886200

- RescueTime - https://www.rescuetime.com/

- Minutes Timer - https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/minutes/id406827163?mt=12