Reverse engineering LogicPro synth files

17 Jul 2017

I really like files. Most programs running on your computer probably store at least some information in files. And the great thing about files is that you, the humble user, can really jam your fingers into them and wiggle them around if you have a mind to. You might be able to modify a file to jump yourself forward 10 levels, migrate your data from a crappy piece of software to a better one, or turn something a funny color. This lets you feel like a badass pirate hacker without having to go to the terrifying trouble of actually breaking any laws.

Before you can do any of this, you have to figure out how the program structures its files. In this post we’re going to reverse engineer the structure of a synth sound (or “patch”) in LogicPro, Apple’s powerful music production software. We’ll use this to write a tiny bit of code that can generate and modify Logic patches. We will do this completely outside of Logic, but files that we’ll create will still be completely usable inside it.

If you create a Logic synth sound that you like, you can save the plugin settings as a preset so that you can quickly load it again in a different track. Logic stores these presets as .pst files. There is nothing at all special about them; they are normal files that behave in exactly the same way as any other file you may be used to. You can view them in Finder, copy and paste them, and even share them over the internet so that other people can try out your sounds for themselves. In order to try out your Phat Sub ES2 patch, I just have to get the phatsub.pst file from you, open it up with the ES2 synth plugin and warn my neighbors that they’re in for an evening of bass in their face.

Like all files, .pst files are just a collection of bits on your hard disk. If we knew how the bits in a file were read and written by Logic, there would be nothing stopping us (apart from perhaps the legal department of Apple Inc.) writing our own tools to create .pst files that could still be read and used by Logic. We’re going to reverse engineer the structure of the .pst file format for the ES M, Logic’s simplest synth. This will allow us to do anything with ES M patches that we can do with code. For example:

- Write our own smart RND function that generates random synths, but only within a range of possibilities that we know we will like

- Write a tool that generates new patches based on the answers to a series of prompts - “Is this a lead, pad or bass?” “Is this a static pad, or do you want motion?”

- Store and share patches in a human-readable format like JSON on Github

- Automatically porting a patch from one synth unit to another (eg. recreating an ES2 synth in Alchemy)

To achieve this, we’re going to:

- Work out how best to view and interpret a

.pst file

- Compare patches that are identical apart from one setting, and use this to figure out which parts of the file are responsible for each setting

- Use a combination of intuition and inspired guesswork to figure out how to translate each of these file parts into a value for the related setting

- Write a tiny bit of Ruby to create a patch of our own

Once you’ve understood this process you will be able to repeat it yourself to reverse engineer the file format for any plugin in Logic.

1. Viewing the file

When inspecting an unfamiliar filetype, it’s worth trying to open it in a standard text editor just in case the creators of the filetype helpfully structured it in a human-readable format along the lines of:

volume: 1.0

decay_time: 1582.1

# …etc

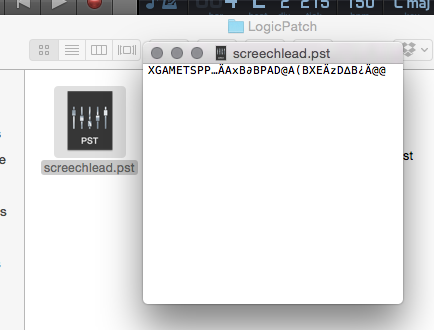

Unfortunately, they rarely do, and Logic is no exception. When opening a .pst file with a standard text editor, like OSX’s default TextEdit, we get total nonsense.

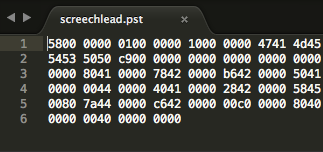

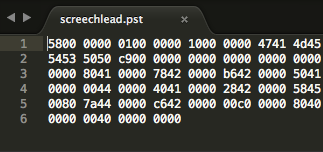

The file was never meant to be viewed like this. We should instead inspect the file using a more advanced editor like Sublime. Sublime is able to realize that the file should not be interpreted as text, and instead allows us to work with the raw bytes.

This will be much easier to work with. Now that we can sensibly view the file, we can start trying to understand it.

2. File whispering

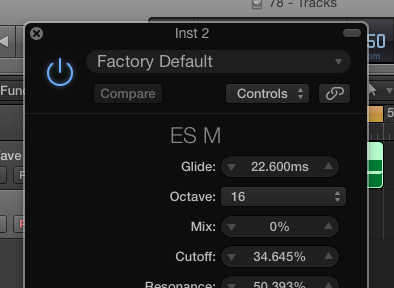

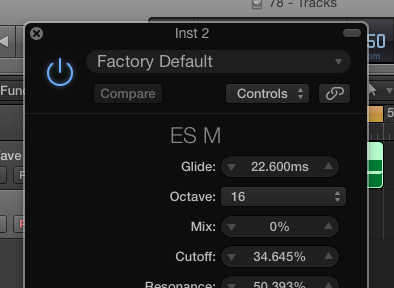

We open up the ESM synth module.

For simplicity we set every parameter in our patch to 0, or whatever you might consider the baseline for the setting. We then save this patch and call it “baseline”. We open it in Sublime and view the bytes.

5800 0000 0100 0000 1000 0000 4741 4d45

5453 5050 c900 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 0040 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 803f 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 80bf 0000 0000

Promisingly, we see that many of the bytes in our basic, initialized patch now read “0”. Now we’re going to adjust the different settings in the ES M one-by-one and see what happens to our patch file. We jam up the cutoff frequency up to 100%, and see that some of the bytes on the third row have changed:

5800 0000 0100 0000 1000 0000 4741 4d45

5453 5050 c900 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 0040 0000 0000 0000 c842 0000 0000 <---

0000 803f 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 80bf 0000 0000

We can infer that these are the bytes that are responsible for storing the cutoff frequency. We do the same thing with volume decay, and see that this time some bytes on the fourth row have changed:

5800 0000 0100 0000 1000 0000 4741 4d45

5453 5050 c900 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 0040 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 803f 0000 0000 0000 0000 0040 1c46 <----

0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 80bf 0000 0000

We can repeat this process to work out the bytes responsible for storing each and every setting.

3. File translating

Finally, we need to work out how the bytes that represent a setting are translated into the value that the setting takes on the synth. There are many standard ways of storing numbers as bytes, and after some fiddling around we realize that this file is storing numbers as 16-bit little-endian floats. Since we can easily write code to manage this conversion for us, a detailed understanding of what this means is not remotely necessary.

We repeat the process of adjusting settings on the synth and comparing the bytes of the resulting patch to our baseline patch. We deduce that the file is structured as:

- A 28 byte-long header that never seems to change. This probably identified the file as an ES M-specific patch

- 14 groups of 8 bytes, where each group of 8 bytes is a different plugin setting stored as a 16-bit little-endian float. The settings are stored in the same order as they are shown in the ES M’s “Settings” display

4. Creating our own patch files

Figuring out the structure of the file was by far the hardest part of this process. It now takes very little, very un-fancy code to start being able to write our own patch files. First we write a small class that takes care of converting from human-readable param names and values to bytes:

class ESMPatch

HEADER_BYTES =

"\x58\x00\x00\x00\x01\x00\x00\x00\

\x10\x00\x00\x00\x47\x41\x4d\x45\

\x54\x53\x50\x50\xC9\x00\x00\x00\

\x00\x00\x00\x00".force_encoding(Encoding::ASCII_8BIT)

SETTING_NAMES = %w{

glide octave mix cutoff resonance filter_decay filter_intensity filter_velo

volume_decay volume_velo overdrive volume pos_bender_range

neg_bender_range tune

}

def initialize(name:, settings:)

missing_settings = SETTING_NAMES.select {|s| settings[s.to_sym].nil?}

if missing_settings.length > 0

raise ArgumentError, "Missing #{missing_settings.join(', ')}"

end

@name = name

@settings = settings

end

def to_bytes

HEADER_BYTES +

SETTING_NAMES.map {|s| number_to_bytes(@settings[s.to_sym])}.join('')

end

def save

File.open(patch.filename, 'w') { |file| file.write(self.to_bytes) }

end

private

def filename

"#{@name}.pst"

end

def number_to_bytes(number)

# See http://apidock.com/ruby/Array/pack

[number].pack('e')

end

end

We can use this class to build and save patches like so:

patch = ESMPatch.new(

name: "mysweetpatch",

settings: {

glide: 0, octave: 16, mix: 62, cutoff: 91, resonance: 13, filter_decay: 512,

filter_intensity: 12, filter_velo: 42, volume_decay: 3456, volume_velo: 1002,

overdrive: 99, volume: -2, pos_bender_range: 4, neg_bender_range: 2,

tune: 0,

}

)

patch.save

Running the above code will create an ES M patch called mysweetpatch.pst with the properties that we specified. We can open it in Logic, and make real life beats with it.

To take this even further, you can imagine packaging up the standard parts of this ES M class into a library that would make it easy to encode the structure any other synth or FX unit that we care to reverse engineer. The additional code we would have to write for each synth could then be as simple as:

class ES2 < LogicSynthUnit

header "\x58\x00\x00\x00\x01\x00\x00\x00"

setting :volume, format: float, default: 0.0

setting :unison, format: bool, default: false

setting :env_1_attack, format: float, default: 0.0

setting :env_1_decay, format: float, default: 0.0

setting :env_1_sustain, format: float, default: 0.0

setting :env_1_release, format: float, default: 50.0

# …and so on

end

Conclusion

LogicPro is just a really, really huge arsenal of tools that create and read files. Apple could theoretically open up the specifications for their file formats and make interoperability between different music programs easier, like Microsoft has done with docx and other Office formats. This wouldn’t really make any sense for anyone, since I don’t believe that anyone would actually want or use this kind of transferability, but it is neat that it’s using the same primitives as Powerpoint.

I really like files. Most programs running on your computer probably store at least some information in files. And the great thing about files is that you, the humble user, can really jam your fingers into them and wiggle them around if you have a mind to. You might be able to modify a file to jump yourself forward 10 levels, migrate your data from a crappy piece of software to a better one, or turn something a funny color. This lets you feel like a badass pirate hacker without having to go to the terrifying trouble of actually breaking any laws.

Before you can do any of this, you have to figure out how the program structures its files. In this post we’re going to reverse engineer the structure of a synth sound (or “patch”) in LogicPro, Apple’s powerful music production software. We’ll use this to write a tiny bit of code that can generate and modify Logic patches. We will do this completely outside of Logic, but files that we’ll create will still be completely usable inside it.

If you create a Logic synth sound that you like, you can save the plugin settings as a preset so that you can quickly load it again in a different track. Logic stores these presets as .pst files. There is nothing at all special about them; they are normal files that behave in exactly the same way as any other file you may be used to. You can view them in Finder, copy and paste them, and even share them over the internet so that other people can try out your sounds for themselves. In order to try out your Phat Sub ES2 patch, I just have to get the phatsub.pst file from you, open it up with the ES2 synth plugin and warn my neighbors that they’re in for an evening of bass in their face.

Like all files, .pst files are just a collection of bits on your hard disk. If we knew how the bits in a file were read and written by Logic, there would be nothing stopping us (apart from perhaps the legal department of Apple Inc.) writing our own tools to create .pst files that could still be read and used by Logic. We’re going to reverse engineer the structure of the .pst file format for the ES M, Logic’s simplest synth. This will allow us to do anything with ES M patches that we can do with code. For example:

- Write our own smart RND function that generates random synths, but only within a range of possibilities that we know we will like

- Write a tool that generates new patches based on the answers to a series of prompts - “Is this a lead, pad or bass?” “Is this a static pad, or do you want motion?”

- Store and share patches in a human-readable format like JSON on Github

- Automatically porting a patch from one synth unit to another (eg. recreating an ES2 synth in Alchemy)

To achieve this, we’re going to:

- Work out how best to view and interpret a

.pstfile - Compare patches that are identical apart from one setting, and use this to figure out which parts of the file are responsible for each setting

- Use a combination of intuition and inspired guesswork to figure out how to translate each of these file parts into a value for the related setting

- Write a tiny bit of Ruby to create a patch of our own

Once you’ve understood this process you will be able to repeat it yourself to reverse engineer the file format for any plugin in Logic.

1. Viewing the file

When inspecting an unfamiliar filetype, it’s worth trying to open it in a standard text editor just in case the creators of the filetype helpfully structured it in a human-readable format along the lines of:

volume: 1.0

decay_time: 1582.1

# …etc

Unfortunately, they rarely do, and Logic is no exception. When opening a .pst file with a standard text editor, like OSX’s default TextEdit, we get total nonsense.

The file was never meant to be viewed like this. We should instead inspect the file using a more advanced editor like Sublime. Sublime is able to realize that the file should not be interpreted as text, and instead allows us to work with the raw bytes.

This will be much easier to work with. Now that we can sensibly view the file, we can start trying to understand it.

2. File whispering

We open up the ESM synth module.

For simplicity we set every parameter in our patch to 0, or whatever you might consider the baseline for the setting. We then save this patch and call it “baseline”. We open it in Sublime and view the bytes.

5800 0000 0100 0000 1000 0000 4741 4d45

5453 5050 c900 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 0040 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 803f 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 80bf 0000 0000

Promisingly, we see that many of the bytes in our basic, initialized patch now read “0”. Now we’re going to adjust the different settings in the ES M one-by-one and see what happens to our patch file. We jam up the cutoff frequency up to 100%, and see that some of the bytes on the third row have changed:

5800 0000 0100 0000 1000 0000 4741 4d45

5453 5050 c900 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 0040 0000 0000 0000 c842 0000 0000 <---

0000 803f 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 80bf 0000 0000

We can infer that these are the bytes that are responsible for storing the cutoff frequency. We do the same thing with volume decay, and see that this time some bytes on the fourth row have changed:

5800 0000 0100 0000 1000 0000 4741 4d45

5453 5050 c900 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 0040 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 803f 0000 0000 0000 0000 0040 1c46 <----

0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000

0000 80bf 0000 0000

We can repeat this process to work out the bytes responsible for storing each and every setting.

3. File translating

Finally, we need to work out how the bytes that represent a setting are translated into the value that the setting takes on the synth. There are many standard ways of storing numbers as bytes, and after some fiddling around we realize that this file is storing numbers as 16-bit little-endian floats. Since we can easily write code to manage this conversion for us, a detailed understanding of what this means is not remotely necessary.

We repeat the process of adjusting settings on the synth and comparing the bytes of the resulting patch to our baseline patch. We deduce that the file is structured as:

- A 28 byte-long header that never seems to change. This probably identified the file as an ES M-specific patch

- 14 groups of 8 bytes, where each group of 8 bytes is a different plugin setting stored as a 16-bit little-endian float. The settings are stored in the same order as they are shown in the ES M’s “Settings” display

4. Creating our own patch files

Figuring out the structure of the file was by far the hardest part of this process. It now takes very little, very un-fancy code to start being able to write our own patch files. First we write a small class that takes care of converting from human-readable param names and values to bytes:

class ESMPatch

HEADER_BYTES =

"\x58\x00\x00\x00\x01\x00\x00\x00\

\x10\x00\x00\x00\x47\x41\x4d\x45\

\x54\x53\x50\x50\xC9\x00\x00\x00\

\x00\x00\x00\x00".force_encoding(Encoding::ASCII_8BIT)

SETTING_NAMES = %w{

glide octave mix cutoff resonance filter_decay filter_intensity filter_velo

volume_decay volume_velo overdrive volume pos_bender_range

neg_bender_range tune

}

def initialize(name:, settings:)

missing_settings = SETTING_NAMES.select {|s| settings[s.to_sym].nil?}

if missing_settings.length > 0

raise ArgumentError, "Missing #{missing_settings.join(', ')}"

end

@name = name

@settings = settings

end

def to_bytes

HEADER_BYTES +

SETTING_NAMES.map {|s| number_to_bytes(@settings[s.to_sym])}.join('')

end

def save

File.open(patch.filename, 'w') { |file| file.write(self.to_bytes) }

end

private

def filename

"#{@name}.pst"

end

def number_to_bytes(number)

# See http://apidock.com/ruby/Array/pack

[number].pack('e')

end

end

We can use this class to build and save patches like so:

patch = ESMPatch.new(

name: "mysweetpatch",

settings: {

glide: 0, octave: 16, mix: 62, cutoff: 91, resonance: 13, filter_decay: 512,

filter_intensity: 12, filter_velo: 42, volume_decay: 3456, volume_velo: 1002,

overdrive: 99, volume: -2, pos_bender_range: 4, neg_bender_range: 2,

tune: 0,

}

)

patch.save

Running the above code will create an ES M patch called mysweetpatch.pst with the properties that we specified. We can open it in Logic, and make real life beats with it.

To take this even further, you can imagine packaging up the standard parts of this ES M class into a library that would make it easy to encode the structure any other synth or FX unit that we care to reverse engineer. The additional code we would have to write for each synth could then be as simple as:

class ES2 < LogicSynthUnit

header "\x58\x00\x00\x00\x01\x00\x00\x00"

setting :volume, format: float, default: 0.0

setting :unison, format: bool, default: false

setting :env_1_attack, format: float, default: 0.0

setting :env_1_decay, format: float, default: 0.0

setting :env_1_sustain, format: float, default: 0.0

setting :env_1_release, format: float, default: 50.0

# …and so on

end

Conclusion

LogicPro is just a really, really huge arsenal of tools that create and read files. Apple could theoretically open up the specifications for their file formats and make interoperability between different music programs easier, like Microsoft has done with docx and other Office formats. This wouldn’t really make any sense for anyone, since I don’t believe that anyone would actually want or use this kind of transferability, but it is neat that it’s using the same primitives as Powerpoint.