What is a self-hosting compiler?

24 Oct 2017

“What language is the Coffeescript compiler written in?” I asked my brilliant, witty and insightful colleague Grzegorz Kossakowski. “The Coffeescript compiler is written in Coffeescript,” he replied. Since this statement is clearly stupid, I denounced him as a liar and an idiot and took back all of the nice things I had said about him.

After I had calmed down and paid for his jacket to be dry-cleaned, Greg was nice enough to explain self-hosting, a technique that really does allow the Coffeescript compiler to be written in Coffeescript. A self-hosting compiler is one that can compile its own source code. I used this information to create Gluby, an asinine new programming language that also has a self-hosted compiler. It is syntactically identical to Ruby, except instead of writing =, you write the actual word EQUALS. You can’t write the actual word EQUALS anywhere else in your program otherwise it will break. This essay explains self-hosting and introduces v0.1 of Gluby.

What is a self-hosting compiler?

Whilst it’s delightful mystifying to say that Coffeescript is written in Coffeescript, in my view it’s also a little misleading. To be more precise but less obtuse, Coffeescript v6 is written in Coffeescript v5, v7 is written in v6, v8 is written in v7 and so on and so forth until we arrive at the singularity and are no longer dependent on this mortal realm or Javascript in any form.

The process of creating a self-hosting compiler begins with a compiler implementation in a language that already exists. Coffeescript was originally written in Ruby. The Scala v2 compiler is also self-hosting, and its v1 was was written in Java. The first version of your new compiler needs to be able to parse your source files (written in your new language) and turn them into something that your computer can execute.

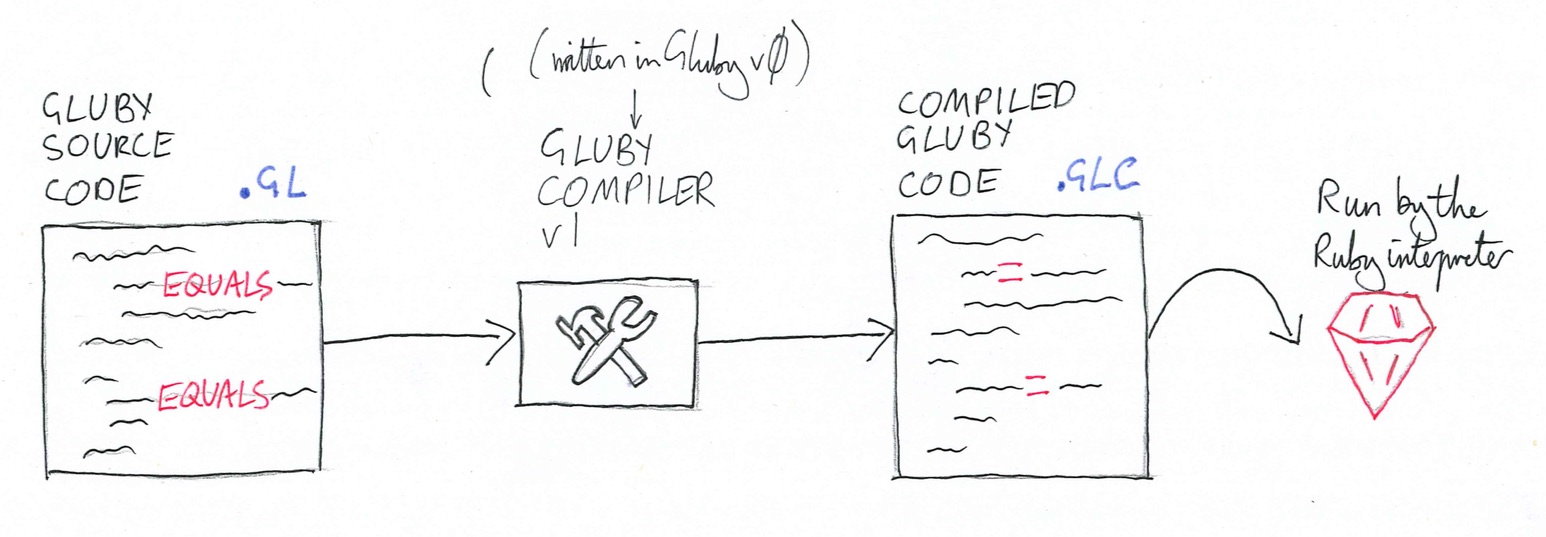

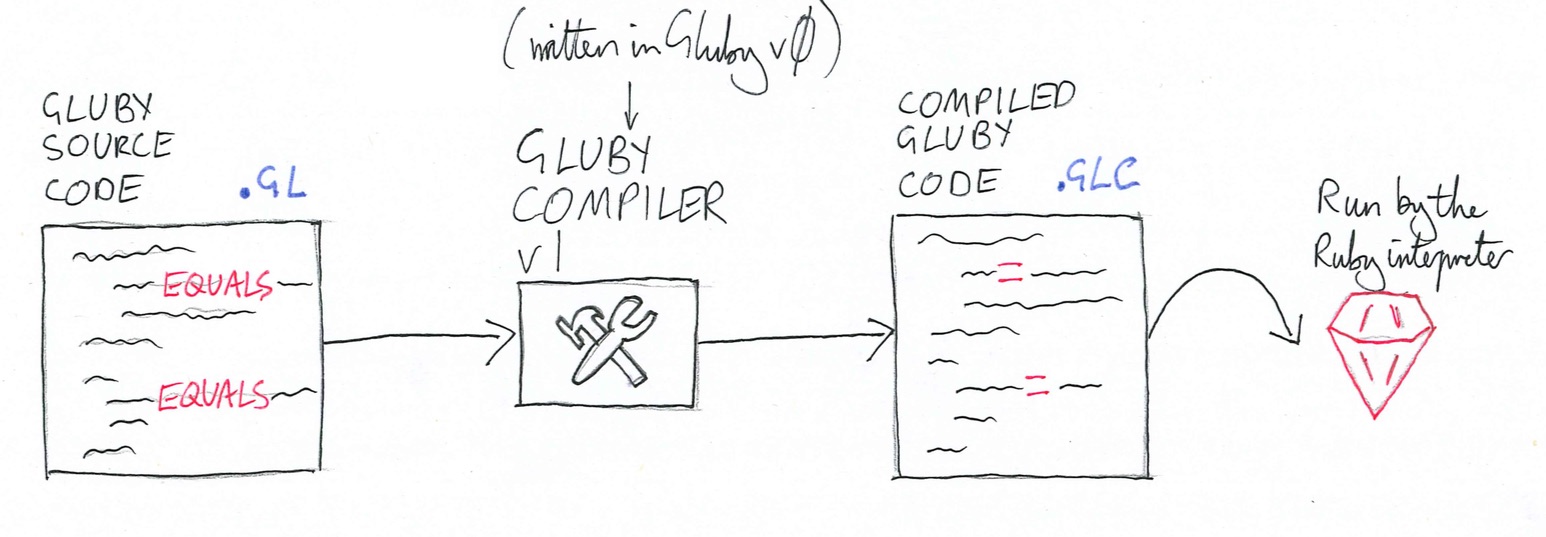

How I made Gluby self-hosting

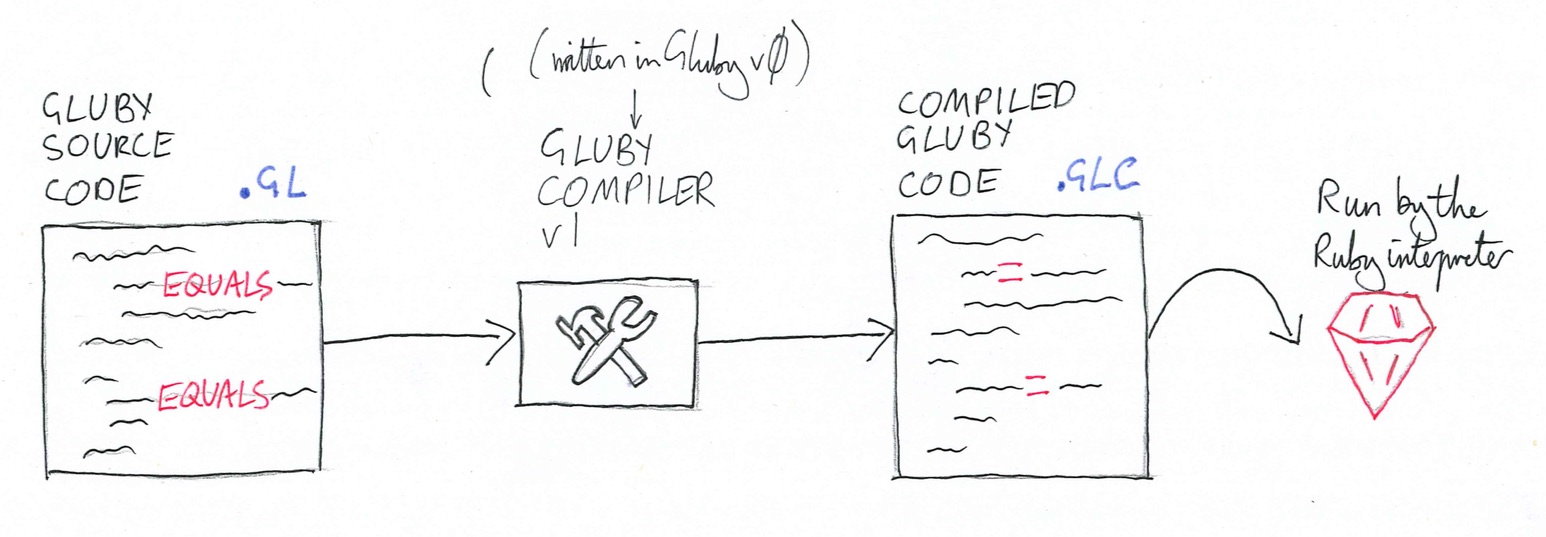

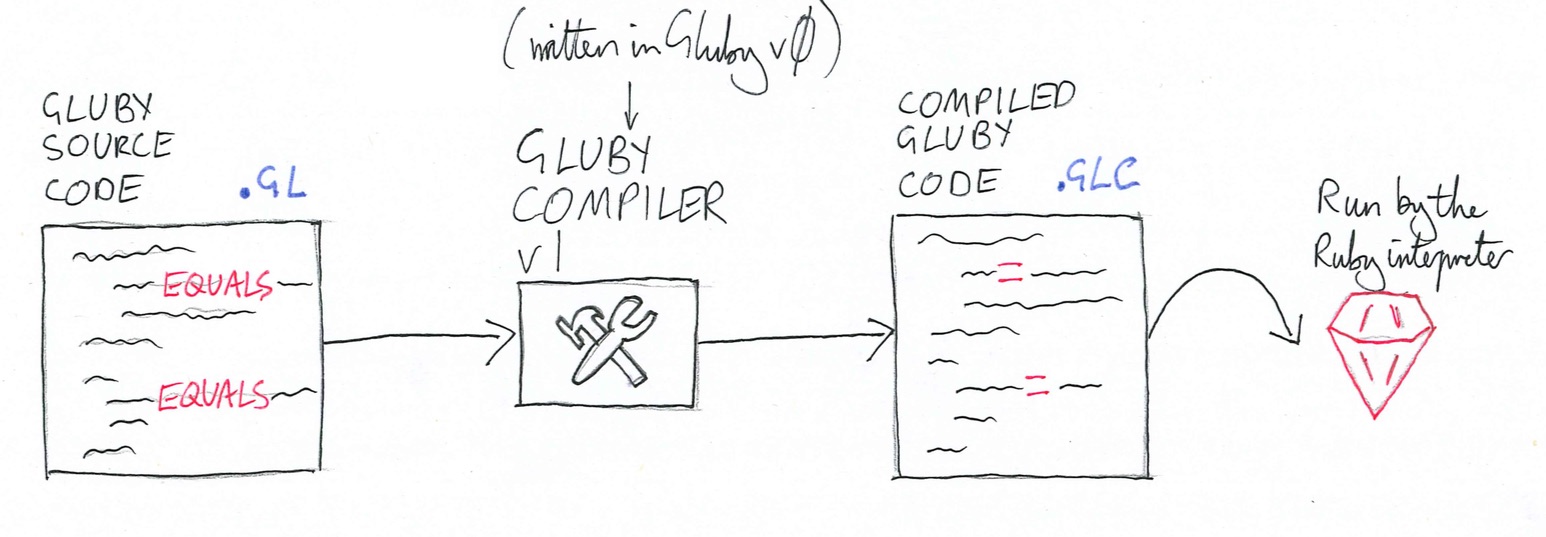

v0 of the Gluby compiler is a Python program that reads a .gl file and turns it into a .glc file by replacing all of the instances of the word EQUALS with actual = signs. The programmer can then execute this compiled Gluby file using the Ruby interpreter.

In order for a language to be made self-hosting, it must first be capable of actually writing compilers. It will probably need to be able to build and manipulate abstract syntax trees, which is by no means straightforward. Gluby sidesteps this issue via wholesale theft all of Ruby’s features and syntax, but since Coffeescript was developing an entirely new syntax it had to build out its functionality the hard way and actually re-implement things like classes, loops and if-statements.

Once a language has been made sufficiently powerful, you simply use it to reimplement its compiler. This compiler is no different to any other program that the language may have been used for. It takes input and produces output, and it just so happens that the input is a source file for that very language, and the output is something that a computer can run.

You then use the old compiler to compile your new one, and now you can throw away the old compiler in the original implementation language forever. You have new source code and a new runnable version of the compiler, so you have no need for the old versions any more. You can continue to swing up the ladder by writing a new version of the language using the current version, compiling it using the current version, and then throwing the current version away forever too.

Gluby v0 - written in Python

Here’s the initial v0 implementation of the Gluby compiler that I used to bootstrap the language. It is written in Python.

from functools import reduce

import sys

if __name__ == '__main__':

input_filename = sys.argv[1]

input_filename_chunks = input_filename.split('.')

output_filename = "%s.blc" % "".join(input_filename_chunks[0:-1])

# "=" is 61 in ASCII

swaps = [(chr(61), 'EQUALS')]

with open(input_filename) as input_f:

with open(output_filename, 'w+') as output_f:

# Read all the lines in the source code

for l in input_f.readlines():

# Make the swaps

new_l = reduce(

(lambda running_l, sw: running_l.replace(swap[1], swap[0])),

swaps,

l

)

# Write out a line to the compiled file

output_f.write(new_l)

Gluby v1 - written in Gluby v0

Here’s v1 of the Gluby compiler. It’s written in Gluby v0, which, remember, is Ruby except you write the actual word EQUALS instead of using the symbol.

input_filename EQUALS ARGV[1]

input_filename_chunks EQUALS input_filename.split('.')

output_filename EQUALS "#{input_filename_chunks[0...-1].join('')}.blc"

# Use ASCII 69 instead of "E" to make sure we don’t replace the string

#"EQUALS" when compiling this program.

swaps EQUALS [[61.chr, 69.chr + 'QUALS']]

File.open(input_filename, "r") do |input_f|

File.open(output_filename, "w+") do |output_f|

input_f.each_line do |l|

new_l EQUALS swaps.reduce(l) do |memo, swap|

memo.gsub(swap[1], swap[0])

end

end

output_f.puts(new_l)

end

end

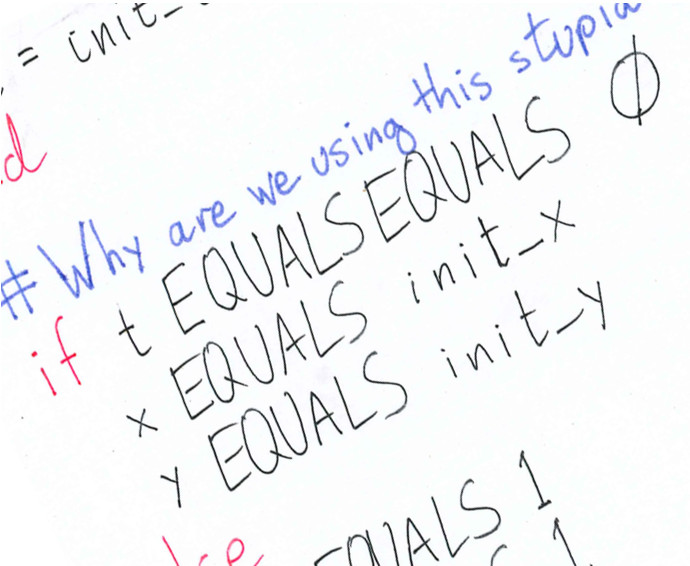

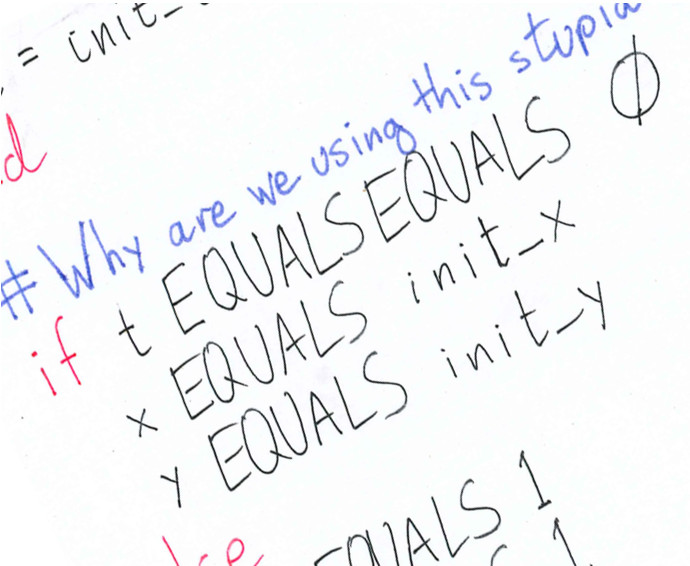

v2 - written in Gluby v1

I’m currently working hard on Gluby v2 - I’m testing out using ALL_HAIL_ROBERT instead of end. Community feedback has been extremely discouraging so I’m trying to find a new, more positive community.

nodes.each do |node|

node.leaves do |leaf|

if leaf EQUALSEQUALS defaultLeaf

total +EQUALS 1

ALL_HAIL_ROBERT

ALL_HAIL_ROBERT

ALL_HAIL_ROBERT

“What language is the Coffeescript compiler written in?” I asked my brilliant, witty and insightful colleague Grzegorz Kossakowski. “The Coffeescript compiler is written in Coffeescript,” he replied. Since this statement is clearly stupid, I denounced him as a liar and an idiot and took back all of the nice things I had said about him.

After I had calmed down and paid for his jacket to be dry-cleaned, Greg was nice enough to explain self-hosting, a technique that really does allow the Coffeescript compiler to be written in Coffeescript. A self-hosting compiler is one that can compile its own source code. I used this information to create Gluby, an asinine new programming language that also has a self-hosted compiler. It is syntactically identical to Ruby, except instead of writing =, you write the actual word EQUALS. You can’t write the actual word EQUALS anywhere else in your program otherwise it will break. This essay explains self-hosting and introduces v0.1 of Gluby.

What is a self-hosting compiler?

Whilst it’s delightful mystifying to say that Coffeescript is written in Coffeescript, in my view it’s also a little misleading. To be more precise but less obtuse, Coffeescript v6 is written in Coffeescript v5, v7 is written in v6, v8 is written in v7 and so on and so forth until we arrive at the singularity and are no longer dependent on this mortal realm or Javascript in any form.

The process of creating a self-hosting compiler begins with a compiler implementation in a language that already exists. Coffeescript was originally written in Ruby. The Scala v2 compiler is also self-hosting, and its v1 was was written in Java. The first version of your new compiler needs to be able to parse your source files (written in your new language) and turn them into something that your computer can execute.

How I made Gluby self-hosting

v0 of the Gluby compiler is a Python program that reads a .gl file and turns it into a .glc file by replacing all of the instances of the word EQUALS with actual = signs. The programmer can then execute this compiled Gluby file using the Ruby interpreter.

In order for a language to be made self-hosting, it must first be capable of actually writing compilers. It will probably need to be able to build and manipulate abstract syntax trees, which is by no means straightforward. Gluby sidesteps this issue via wholesale theft all of Ruby’s features and syntax, but since Coffeescript was developing an entirely new syntax it had to build out its functionality the hard way and actually re-implement things like classes, loops and if-statements.

Once a language has been made sufficiently powerful, you simply use it to reimplement its compiler. This compiler is no different to any other program that the language may have been used for. It takes input and produces output, and it just so happens that the input is a source file for that very language, and the output is something that a computer can run.

You then use the old compiler to compile your new one, and now you can throw away the old compiler in the original implementation language forever. You have new source code and a new runnable version of the compiler, so you have no need for the old versions any more. You can continue to swing up the ladder by writing a new version of the language using the current version, compiling it using the current version, and then throwing the current version away forever too.

Gluby v0 - written in Python

Here’s the initial v0 implementation of the Gluby compiler that I used to bootstrap the language. It is written in Python.

from functools import reduce

import sys

if __name__ == '__main__':

input_filename = sys.argv[1]

input_filename_chunks = input_filename.split('.')

output_filename = "%s.blc" % "".join(input_filename_chunks[0:-1])

# "=" is 61 in ASCII

swaps = [(chr(61), 'EQUALS')]

with open(input_filename) as input_f:

with open(output_filename, 'w+') as output_f:

# Read all the lines in the source code

for l in input_f.readlines():

# Make the swaps

new_l = reduce(

(lambda running_l, sw: running_l.replace(swap[1], swap[0])),

swaps,

l

)

# Write out a line to the compiled file

output_f.write(new_l)

Gluby v1 - written in Gluby v0

Here’s v1 of the Gluby compiler. It’s written in Gluby v0, which, remember, is Ruby except you write the actual word EQUALS instead of using the symbol.

input_filename EQUALS ARGV[1]

input_filename_chunks EQUALS input_filename.split('.')

output_filename EQUALS "#{input_filename_chunks[0...-1].join('')}.blc"

# Use ASCII 69 instead of "E" to make sure we don’t replace the string

#"EQUALS" when compiling this program.

swaps EQUALS [[61.chr, 69.chr + 'QUALS']]

File.open(input_filename, "r") do |input_f|

File.open(output_filename, "w+") do |output_f|

input_f.each_line do |l|

new_l EQUALS swaps.reduce(l) do |memo, swap|

memo.gsub(swap[1], swap[0])

end

end

output_f.puts(new_l)

end

end

v2 - written in Gluby v1

I’m currently working hard on Gluby v2 - I’m testing out using ALL_HAIL_ROBERT instead of end. Community feedback has been extremely discouraging so I’m trying to find a new, more positive community.

nodes.each do |node|

node.leaves do |leaf|

if leaf EQUALSEQUALS defaultLeaf

total +EQUALS 1

ALL_HAIL_ROBERT

ALL_HAIL_ROBERT

ALL_HAIL_ROBERT