HTTPS in the real world

28 Nov 2018

In cryptography, trust is mathematically provable. Everything else is just faith.

When you begin reading any introductory explanation of HTTPS, you are quickly whisked away to an alien planet inhabited by a savage society. On this world the entire population knows at least the basics of offensive computer networking, and coffee shop wi-fi connections are overflowing with attackers trying to steal each others’ Facebook passwords. Desperately holding these attackers at bay are nothing more than the raw power of HTTPS and a handful of trusted Certificate Authorities (CAs) run by incorruptible treefolk who live in the mountains.

The world of the HTTPS introduction makes no claims to reality. It exists only to highlight how incredible it is that an attacker can capture every single packet of HTTPS data that your browser exchanges with Facebook, and yet still have no idea what your password is. It shows just how powerful a system can be when you combine computers with incorruptible treefolk who live in the mountains, and how even just a tiny bit of total, no-questions-asked faith in a central authority can go a long way.

In the real world there’s no such thing as incorruptible treefolk, and there’s no such thing as no-questions-asked faith in a central authority that doesn’t also quickly wreck civilization. But the real world has still managed to piece together a very serviceable public-key cryptography system by patching over the holes and omissions and naivety of the introductory world with a tartan of secondary systems known collectively as “Public Key Infrastructure” (PKI).

PKI is neither perfect nor particularly elegant, but it still does a admirable job of coping with a wide range of real world complications. In this essay we’re going to look at three such complications. We’ll see how PKI addresses the facts that 1) your own private key might not stay private; 2) your Certificate Authority’s private key might not stay private; and 3) Certificate Authorities are not actually staffed exclusively by incorruptible treefolk who live in the mountains.

None of these complications affect the fundamental algorithms of public-key cryptography. Elliptic curve Diffie–Hellman is just as valid in the real world as it ever was in the world of the HTTPS introduction. If a message appears to be signed by Alice’s private key then we can still be certain that whoever signed it really is in possession of said key. However, in the real world, we have to take extremely seriously the possibility that this person might not have been Alice. We have to go to some quite extreme, fiddly, and fascinating lengths to build up enough faith to conclude that it probably was.

Complication 1: Your private key may not stay private

Your private key is just a file on a server. Files on servers get stolen all the time - just ask Uber, Equifax, Facebook, Target, Yahoo, and the DNC. Even worse, your private key is needed for negotiating every single TLS connection that is made with your servers, and is therefore in constant use. It can’t simply be stashed away inside a lockbox inside a bank vault and never touched.

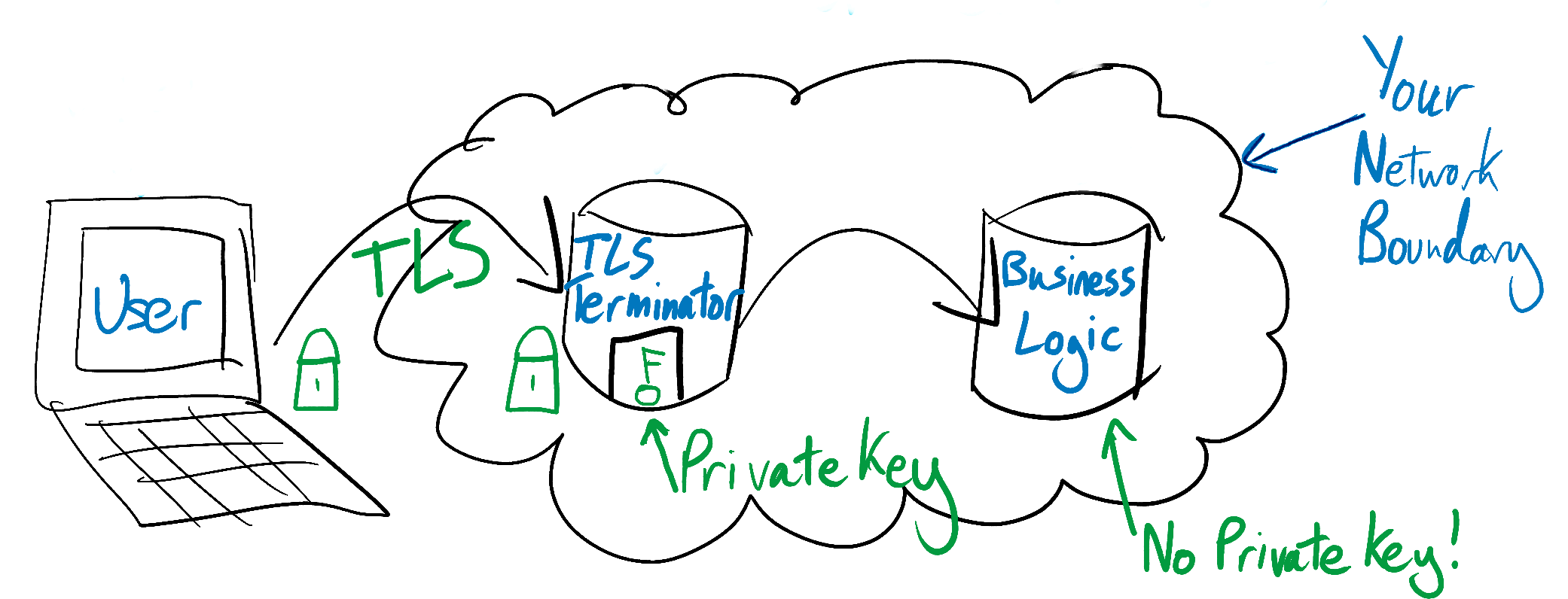

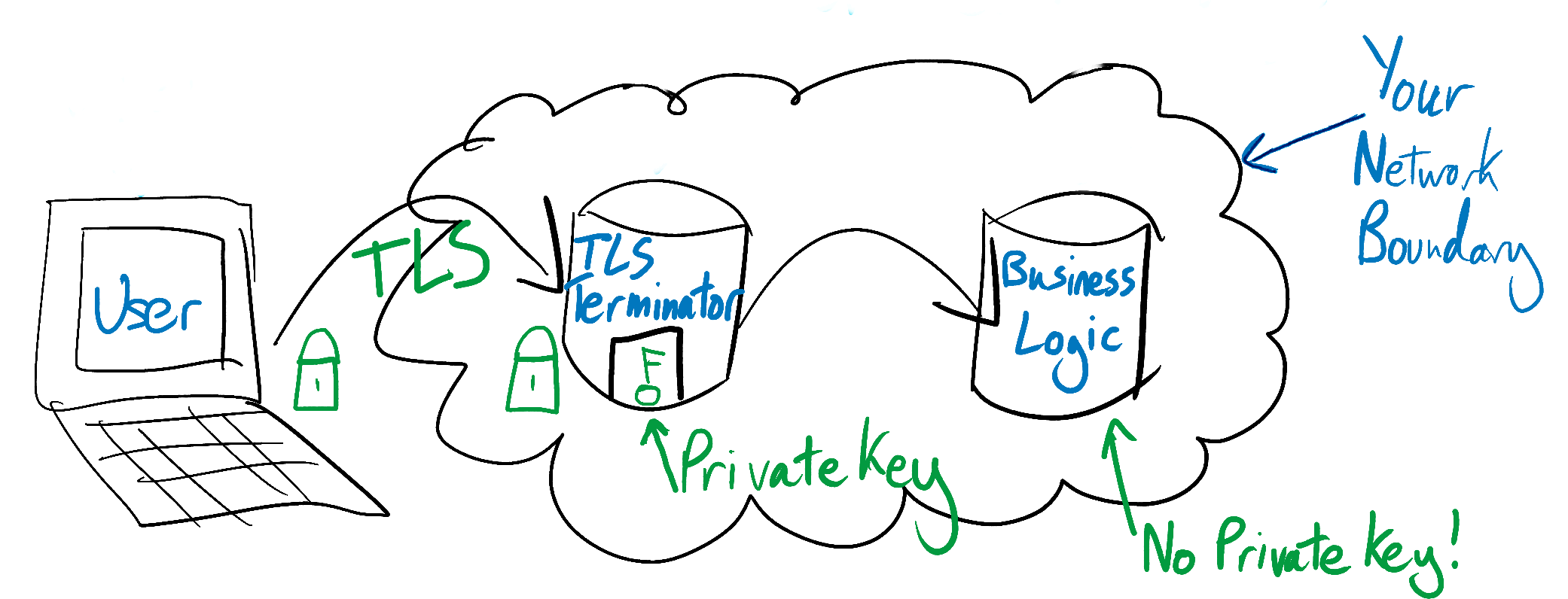

You can take steps to keep your private key safe. For example, you can do all of your TLS connection negotiation on dedicated “TLS-termination” servers. These servers’ only job is decryption, and they are the only machines in your fleet that contain a copy of your private key. Once they have decrypted an HTTPS request, they forward it on to other servers to execute your business logic. Since the TLS-termination servers have already decrypted the request, these business logic servers do not need access to your private key.

This limits the number of machines with access to your private key, and means that you can lock down access to the TLS-termination servers extremely aggressively. They can be isolated from the rest of your server fleet, and access to them can be limited to a very small set of your employees. They can be watched by particularly sensitive monitoring, and touched only with a particularly heightened level of paranoia.

Plenty of things can still go wrong, and private keys can still be compromised. If this happens to you, an attacker in possession of your private key will be able to snoop on your users’ encrypted traffic with your website, or to simply impersonate your servers wholesale. You therefore need to be able to quickly notify the world that your key has been compromised and that everyone should stop having faith in your certificate. You need to be able to revoke your certificate.

Certificate revocation

A TLS certificate is an almost entirely self-contained passport. Its signature can be verified using nothing more than mathematics and a copy of all of the other certificates in its chain of trust (see below), with no need to talk to any outside, central authority.

Since TLS was designed without a central verification authority, it was also designed without a central “un-verification” authority. If your private key gets compromised then this doesn’t somehow stop the mathematics that went into its signature from being correct. Anyone who has access to your key can do a perfect cryptographic impression of you.

Un-verification, or “certificate revocation”, is challenging, and has been for decades. The first attempt at a process for disavowing certificates was the Certificate Revocation List (CRL) system. A CRL is a monolithic list of revoked certificates, maintained by a CA. When a certificate owner wants to revoke a certificate (perhaps because they believe it has been compromised), they inform CRL operators, who add this revocation to their lists. When a browser wants to know whether a mathematically valid certificate is still faith-worthy, it checks the certificate against a CRL. If the browser finds the certificate on the CRL then it knows that the certificate has been disavowed by its owner. The browser can calmly freak out and drop the connection.

The CRL process does work, and is in principle quite reasonable. However, CRLs are not updated frequently, and as the number of revoked certificates grows bigger and bigger, downloading and checking a CRL becomes slower and slower and less and less practical. On top of this, if a browser is unable to talk to a CRL server then it suddenly has no good options. It could count the verification as failed and refuse to continue making the connection. But this would prevent all users from accessing the affected domain, even though there is probably no actual security problem. It could count the verification as successful, and proceed as normal. But this would mean that an attacker could disable CRL checks entirely by blocking a victim’s network connection to a CRL server, at the time when these checks were needed the most.

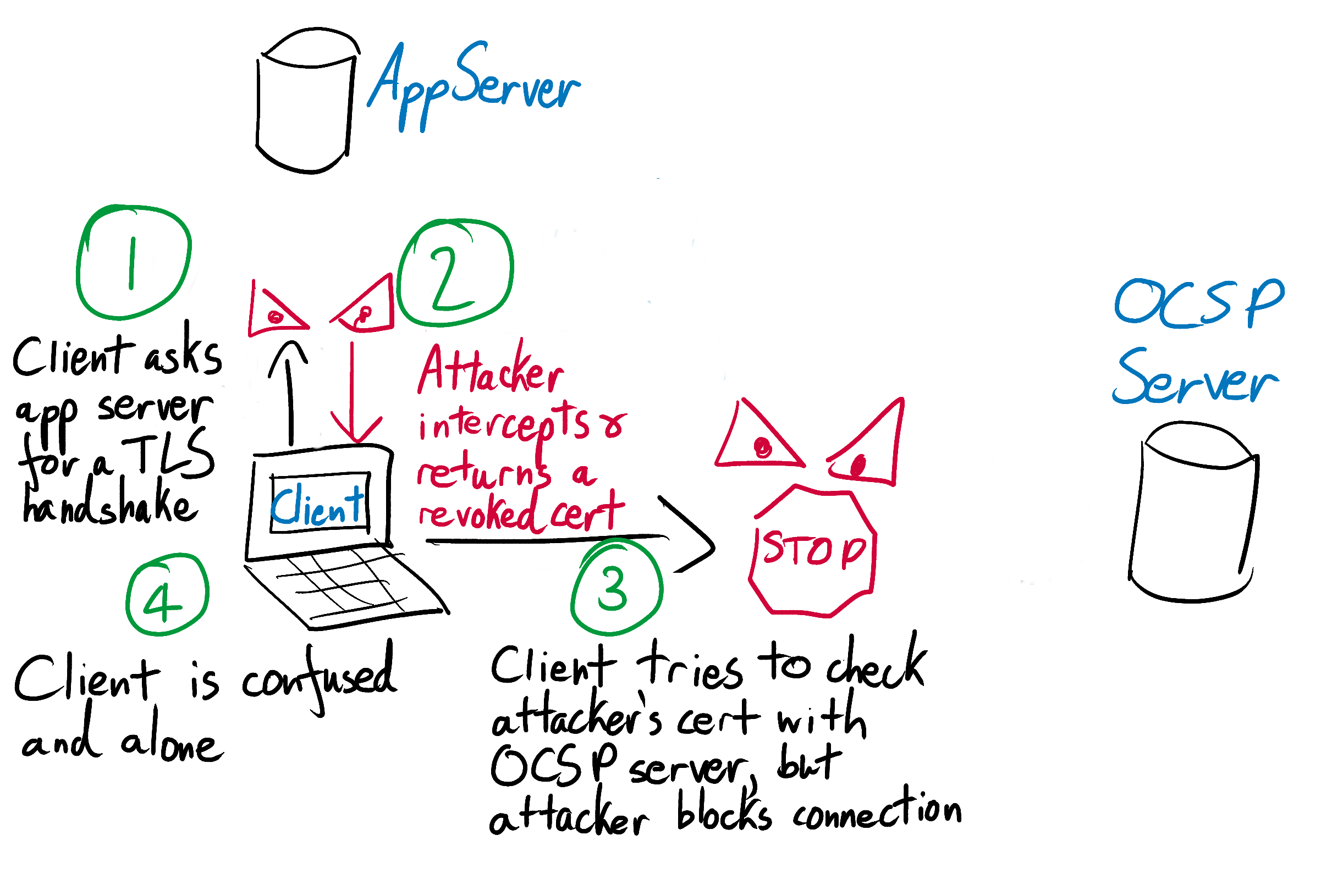

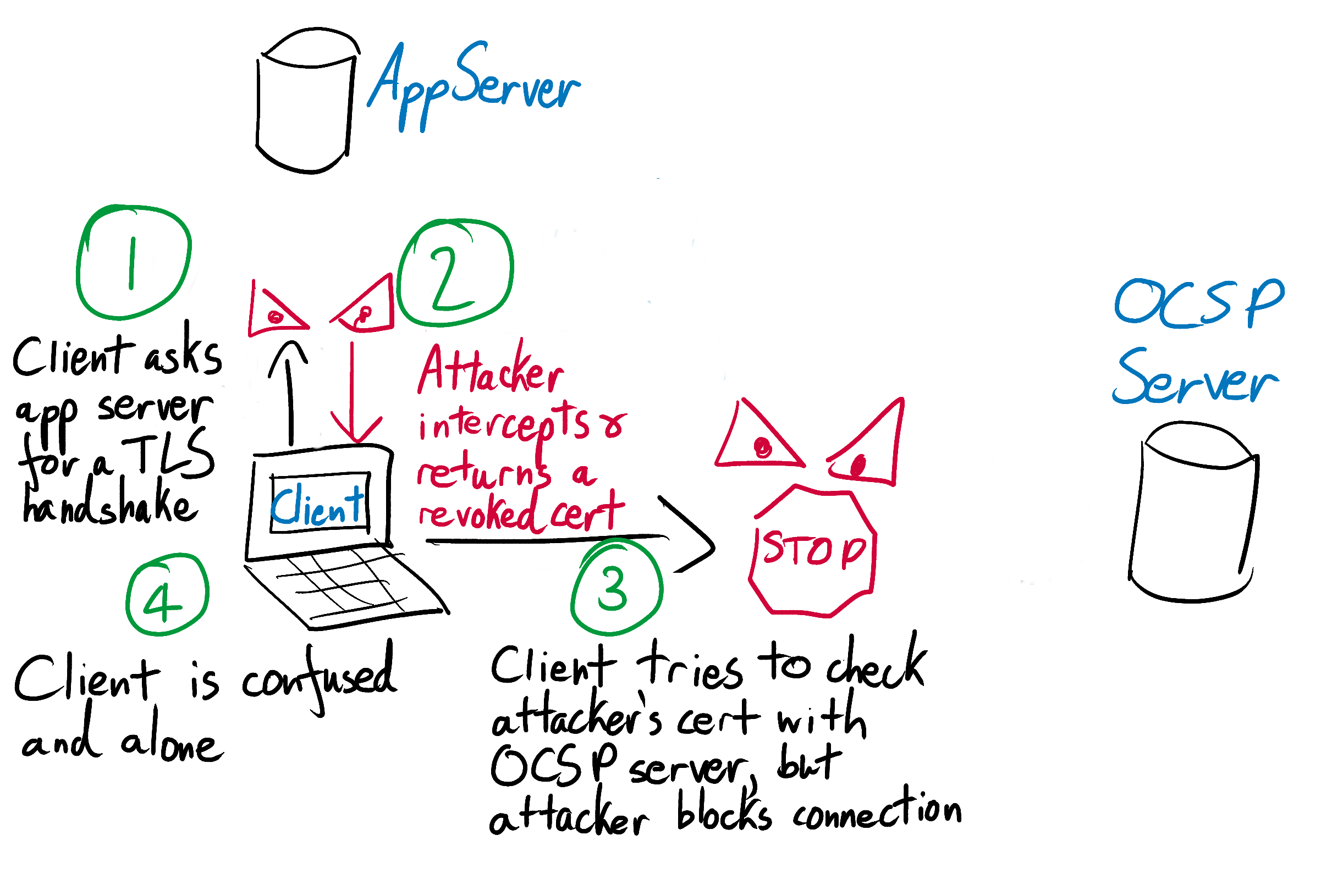

The Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP) is an attempt to scale certificate revocation. Instead of asking a CRL server for the entire list of revoked certificates, a browser asks a certificate’s designated OCSP server (specified on the certificate itself) the simple question “has certificate X been revoked?” The server quickly replies “yes” or “no”, and the browser proceeds accordingly.

Since an OCSP check doesn’t require downloading a huge list of revoked certificates, it is much speedier and more lightweight than a CRL check. However, vanilla OCSP still has no good answer to the question of what to do when the OCSP server is down.

Happily, the problem of the missing OCSP server is addressed by the next iteration of OCSP: OCSP-stapling. In OCSP-stapling, it is the website server’s responsibility to query the OCSP server to check if its own certificate is still valid. The OCSP server checks its revocation lists, and if the certificate is still valid then it sends the website server back a signed confirmation of this fact. The website server attaches or “staples” this confirmation onto its certificate, and presents this augmented certificate to browsers.

Browsers can verify that the certificate’s stapled validation is legitimate and has been signed by the OCSP server. If the validation checks out, browsers can take it as assurance that the certificate has not yet been revoked. The validation expires after a short period of time, typically 24 hours, so the website operator must keep re-validating and re-stapling its certificate. If the certificate ever becomes revoked, the OCSP server will start refusing to provide new validations. Without a recent, signed OCSP confirmation, clients will refuse to trust the certificate. Since OCSP servers sign their validations using their own private keys, attackers cannot trick browsers into accepting revoked certificates by faking and stapling their own OCSP attestations.

OCSP-stapling is a relatively new innovation, and for now is only enabled for certificates with the Must-Staple flag set to true. Certificates without this flag set do not perform or staple OCSP validations, but their Must-Staple flag tells clients that this is OK.

Certificate revocation is a crucial tool for responding to key compromises. However, you can only revoke your certificate if you know that you’ve been hit. Sadly, sometimes you won’t. But you can reduce the impact of even an undiscovered theft of your private key by frequently expiring and rotating your TLS certificates.

Key rotation

Your certificate’s expiration date is recorded in a field on the certificate. After its expiry date, browsers will consider it just as untrustworthy as a certificate that is unsigned or clearly forged. If an attacker steals the private key for a certificate that expires in 5 years time, then that’s 5 years of future traffic to your website that they can decrypt if they can keep their breach undetected. If they silently steal the private key for a certificate that expires in 3 months then that’s still very bad, but at least in 3 months time their fun will automatically expire.

Setting short expiry periods and frequently rotating your certificates can therefore reduce the fallout of even an undiscovered key compromise. Doing so does require you to go to the effort of regularly replacing your certificates, but can be made very straightforward with the right tools.

Complication 2: A CA’s private key may not stay private

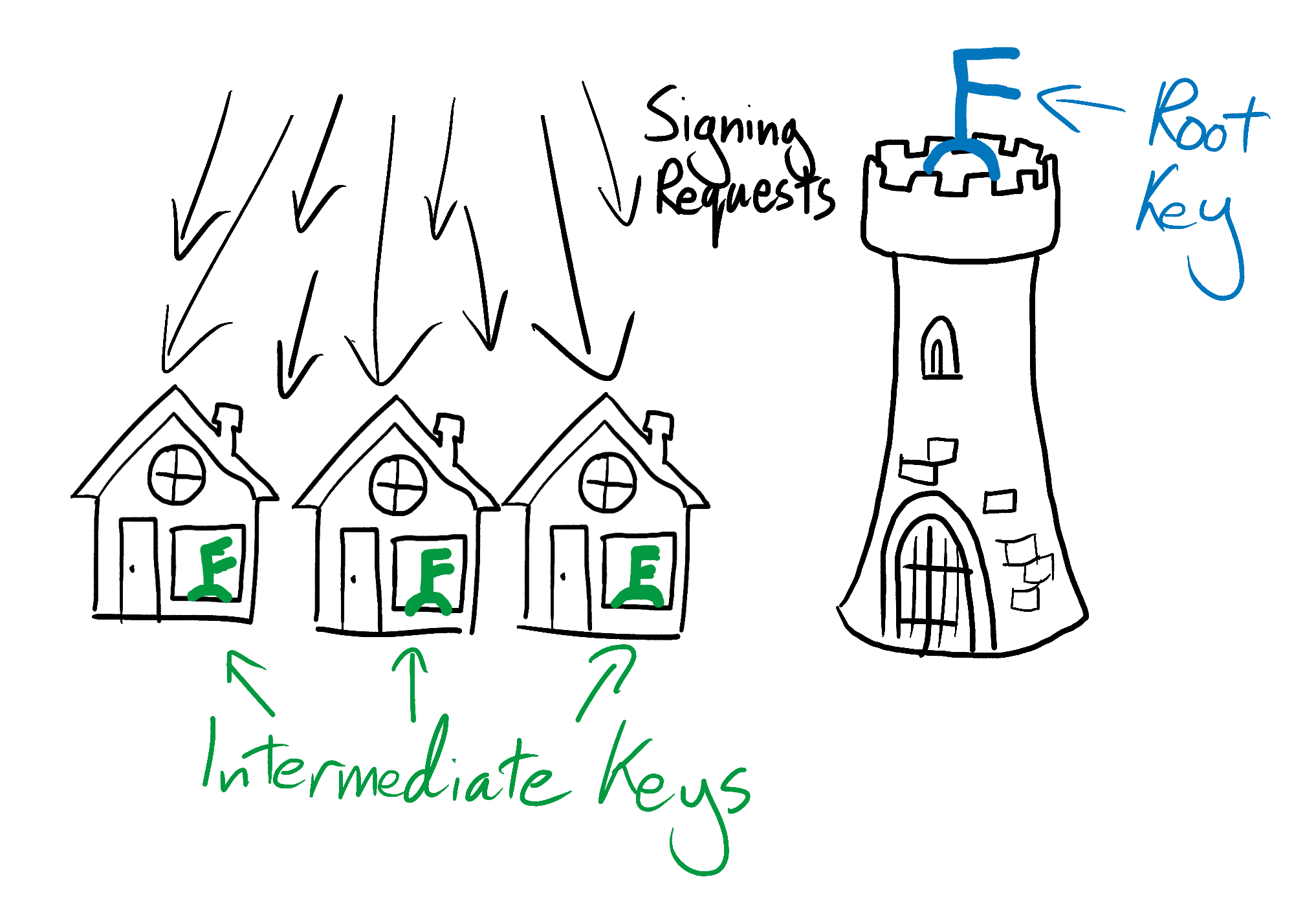

If an attacker steals your private key then they can impersonate you. But if they steal the private key of a CA then they can impersonate anyone. CAs take their own steps to prevent this from happening, and to mitigate the fallout if it ever does.

There are around 60 Root CAs whose certificates are hardcoded into browsers’ trust stores. If a Root CA’s certificate ever needed to be revoked then that CA would instantly lose the source of all its power. All of the certificates it had ever signed would be invalidated, and it would be unable to sign any new certificates until a new version of the browser was released containing a new, uncompromised, hardcoded certificate.

A CA can reduce the consequences of a breach of its root private key by delegating some or all of their root key’s power to an “intermediate CA”. It can do this by using its root key to sign an intermediate CA certificate, and using this intermediate CA certificate to sign its customers’ certificates. When a browser comes to check the validity of one of these certificates, it will see that it was signed by the intermediate CA, and that the intermediate’s certificate was signed by a Root CA. The browser has faith in the Root CA, and it sees that the Root CA has faith in the intermediate CA because it signed the intermediate CA’s certificate. The browser therefore trusts the customer’s certificate - any friend of Root’s is a friend of mine.

To keep their precious secrets safe, CAs typically don’t use their root keys for day-to-day signing. Instead they issue themselves with intermediate CA certificates, signed by their root key. They use these intermediate certificates for signing their customers’ certificates, and keep their root key completely locked down in a specialized, hardened machine called a hardware security module (HSM). An HSM swallows the key and makes it close to impossible for anyone to ever retrieve it again, even if they have physical access to the machine and a large suite of power tools. However, it does this in such a way that it can still use the key to sign certificates. On the rare occasions when the root private key is needed to sign a message, the HSM can still read the message and produce a signature. Since the root key is rarely used and is kept deep inside the HSM’s reinforced belly, it is very unlikely to be compromised.

Make no mistake; if the key for a workaday intermediate certificate were stolen then this would still be spectacularly bad. To mitigate the damage, the afflicted organization would have to revoke the compromised intermediate certificate. All of the certificates signed by it would be invalidated, and would cease to be accepted by browsers.

However, instead of having to wait for a new browser release before being able to sign keys again, the CA would be able to go to its almighty, divine, uncompromised root key and ask it to sign a new, intermediate CA certificate. The organization would be able use this new intermediate certificate to reissue all the certificates that had been issued by the compromised intermediate certificate. Whether anyone should want a reissued certificate from a CA that had been breached in this way is a separate question.

Complication 3. The CAs that you trust to do the right thing will not always do the right thing

Remember - in cryptography, trust is mathematically provable. Everything else is faith.

Judeo-Christian God understood this difference. He didn’t sign the Bible with his private key. That would be trust, not faith. You can audit God and build a plausible case for faith. You can read the unsigned Bible, make allowances for the bits that have aged poorly, and talk to your priest and rabbi about the bits that have aged really really poorly. But after that you’ve still got to have pure faith that the voice you think you hear at night really is God, and not your deep desire for there to be more to life than this.

You can audit Certificate Authorities too, or more likely read an audit that someone else has done, or even more likely have faith that someone somewhere has done an audit and that someone else has read it. You can read the Wikipedia page on TLS and skim the proofs of why factoring large numbers is difficult. But at a certain point you’ve got to have not-entirely-proven faith that the squishy, human bits of the system are working just as well as the cryptography. I trust that I am talking to someone with access to facebook.com’s private key. I have nothing more than faith that Facebook hasn’t had their private key stolen.

If you don’t have faith in Judeo-Christian God then you probably won’t get invited to the church summer picnic, and depending on who turns out to be right you might burn in hell for all eternity. But if you don’t have faith in HTTPS then you can’t use the internet. So whenever end-users like you or I open a new tab, we place our faith in our browser to keep us safe and secure. Our browser vendor does a lot of this work on its own. It makes sure that our browser’s code is fortified with vitamins and stack safety, and that its JavaScript implementation conforms to the ECMA spec. But our browser vendor delegates our faith in identity verification to the CAs whose public keys it hardcodes into its trust store.

We can break down this faith into two parts. The first, which we have discussed already, is that the CA will keep its signing keys safe from compromise. The second is that the CA itself won’t use these keys to do anything stupid or malicious.

Root CAs have the absolute power to sign certificates for any domain. There’s no cryptography preventing them from deliberately or accidentally abusing this power; only process, monitoring, and the threat of being removed from browser root trust stores. Our browser vendor ensures that each root CA is worthy of faith through checks and audits of its processes. If any CA is found lacking then it may be expelled from the browser’s list of root authorities, instantly and completely destroying that CA’s business.

Indeed, Symantec’s CA operation was recently untrusted by Chrome and other major browsers, in part because it had been repeatedly mis-issuing certificates for domains to people who did not control them. The browsers took this drastic action because the whole and sole point of a CA is that they can be relied on to only ever issue certificates to the right people.

The standards that CAs should follow are agreed upon at the Certificate Authority/Browser (CA/B) Forum. For example, whenever a customer asks a CA to sign a certificate for a domain, the CA is first supposed to confirm that the customer really does own the domain. 2 of the most straightforward and easily automated methods are those used by Let’s Encrypt. Let’s Encrypt requires their customers to either provision a specific DNS record for the domain they are requesting a certificate for, or to place a specially formatted file at a specific path (eg. example.com/asdkjnsad13p87gdbjhsdjbhiup). Neither of these challenges should be completable without direct control over a domain. If a Let’s Encrypt customer is able to complete one of them, Let’s Encrypt takes this as proof that this customer really does control the domain, and issues them with the certificate that they requested.

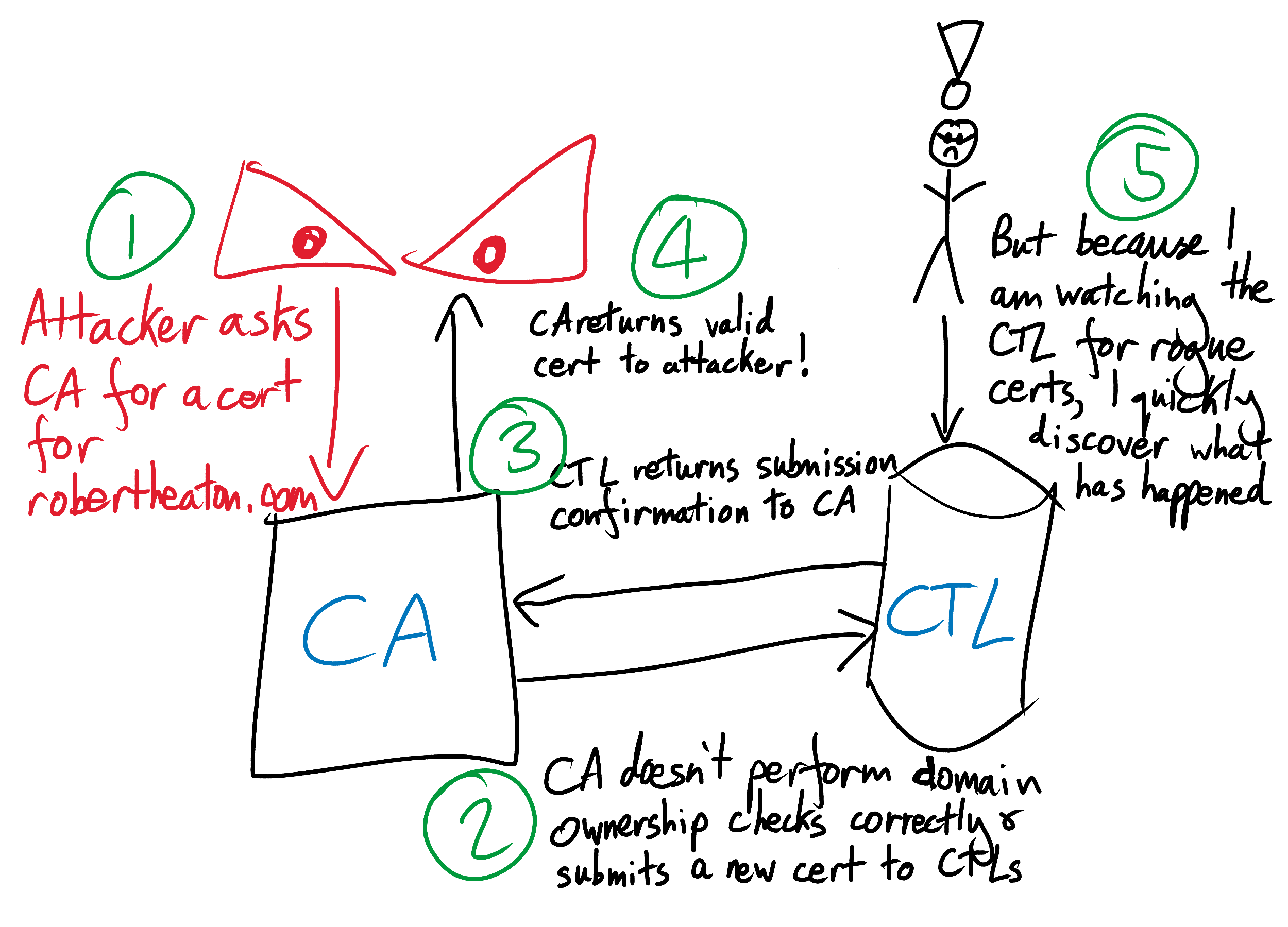

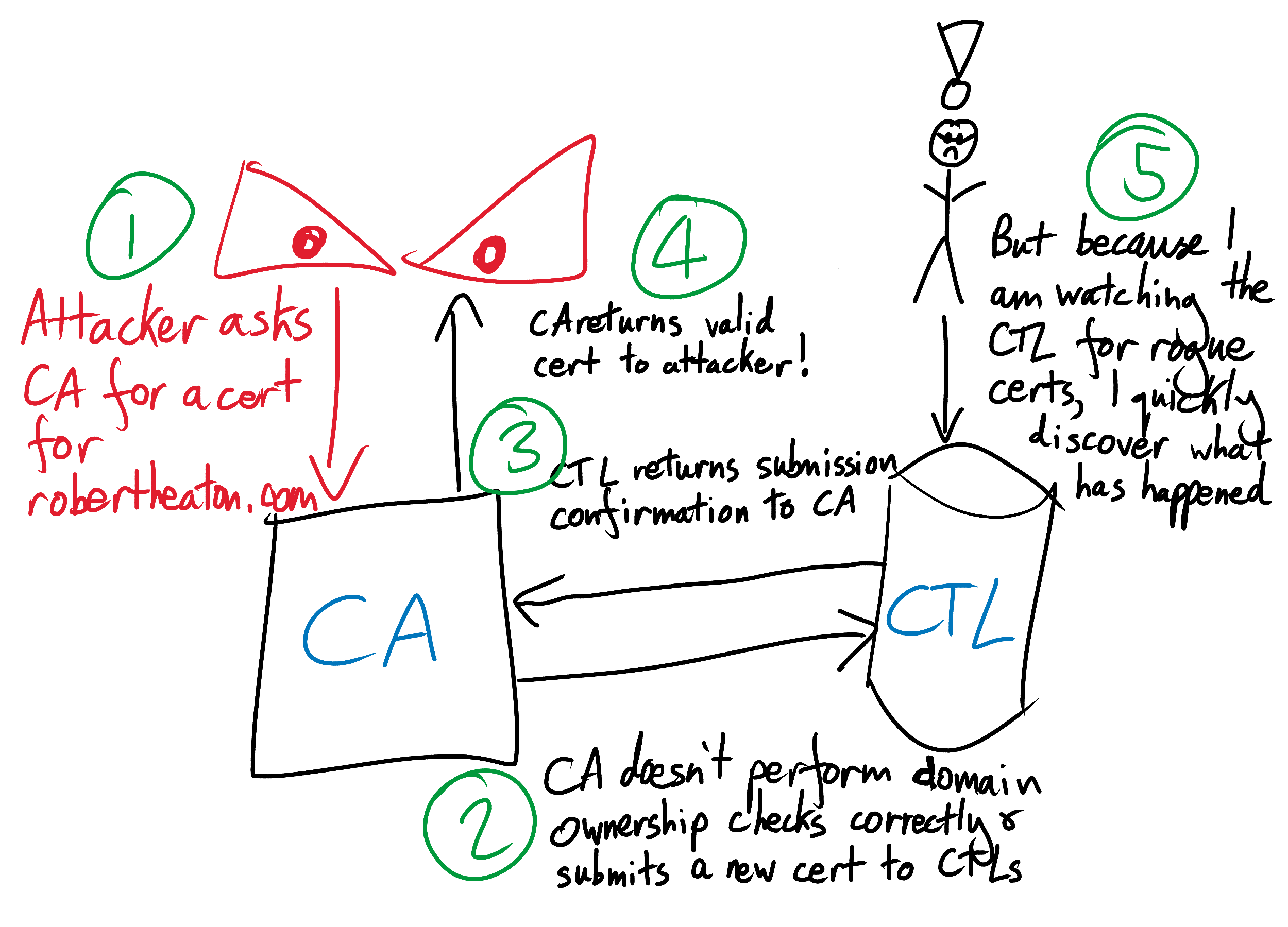

But later, when a browser is inspecting this certificate and deciding whether to have faith in it, there is no way for it to know for certain whether the CA that signed it really did properly verify the domain’s ownership. Lax CA domain verification can and does result in the issuance of certificates for domains to customers who don’t control them. This undermines the very foundation of public-key cryptography. To forcefully encourage CAs to improve, and to more rapidly uncover those times when they screw up, PKI has recently grown another limb: Certificate Transparency Logs.

Certificate Transparency Logs

Until recently, domain owners had no systematic way of finding out if a CA had mis-issued a certificate for their domain. The first they knew about the problem could easily be when their users began getting owned. There was no announcement when a new certificate was issued, and no databases of issued certificates that domain owners could inspect.

To try to uncover mis-issued certificates faster and more consistently, Google has spearheaded the creation of a system called the Certificate Transparency Log (CTL). CTLs makes it easy for domain owners to find out when a CA has issued and signed a certificate for their domain. They make the previously silent process of certificate issuance much noisier and therefore more easily observable.

A CTL is a public log of public certificates. There are many CTLs: Google runs several, Comodo runs one, and some guy runs one from behind a sofa in London. When a CA signs a new certificate for a customer, the CA is required to submit it to at least 2 CTLs. When they do, the operator of each CTL adds the certificate to their public log and sends the CA back a signature that says “I, Ms. C.T.L. Operator, have received this certificate and will add it to my log.” The CA appends these signatures to the original certificate, since they prove that it has met its responsibility to submit it to 2 CTLs. The CA then gives the signed and provably logged certificate to its customer.

Domain owners can now monitor CTLs for newly issued certificates on their domain that they don’t recognize. They can do this either by downloading the (completely public) data and sifting through it themselves, or by using a service like crt.sh to sift through it for them. If they see a certificate that they don’t recognize, they can freak out, try to get it revoked, and try to get the CA that signed it into trouble.

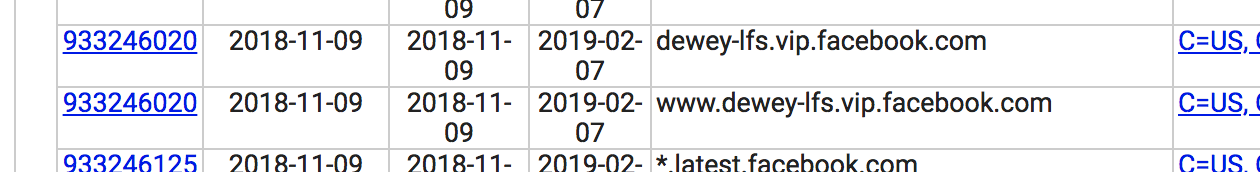

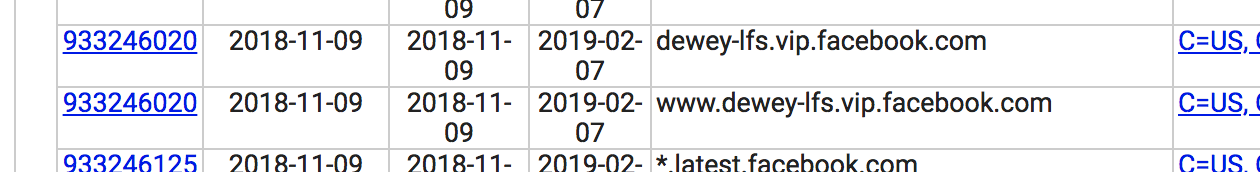

CTLs do have unfortunate side-effects. Services like crt.sh are useful tools not only for domain owners, but for attackers too. Attackers can search crt.sh for all certificates for subdomains of a particular website, and can scour this list for less well-known and perhaps less protected targets. For example, I’m sure that www.dewey-lfs.vip.facebook.com is perfectly well-secured, whatever it is, but I bet that it’s not watched quite as closely as the main facebook.com infrastructure.

Since CTLs mean more work and more scrutiny for CAs, we might expect them to decline or accidentally forget to play along. To force CAs to comply, browsers refuse to trust TLS certificates without at least 2 valid signatures from CTL operators. If a CA tries to evade scrutiny by not submitting a new certificate to 2 CTLs, they will not have 2 valid CTL signatures that they can append to it. Without these signatures the certificate will not be trusted by browsers and so will be useless.

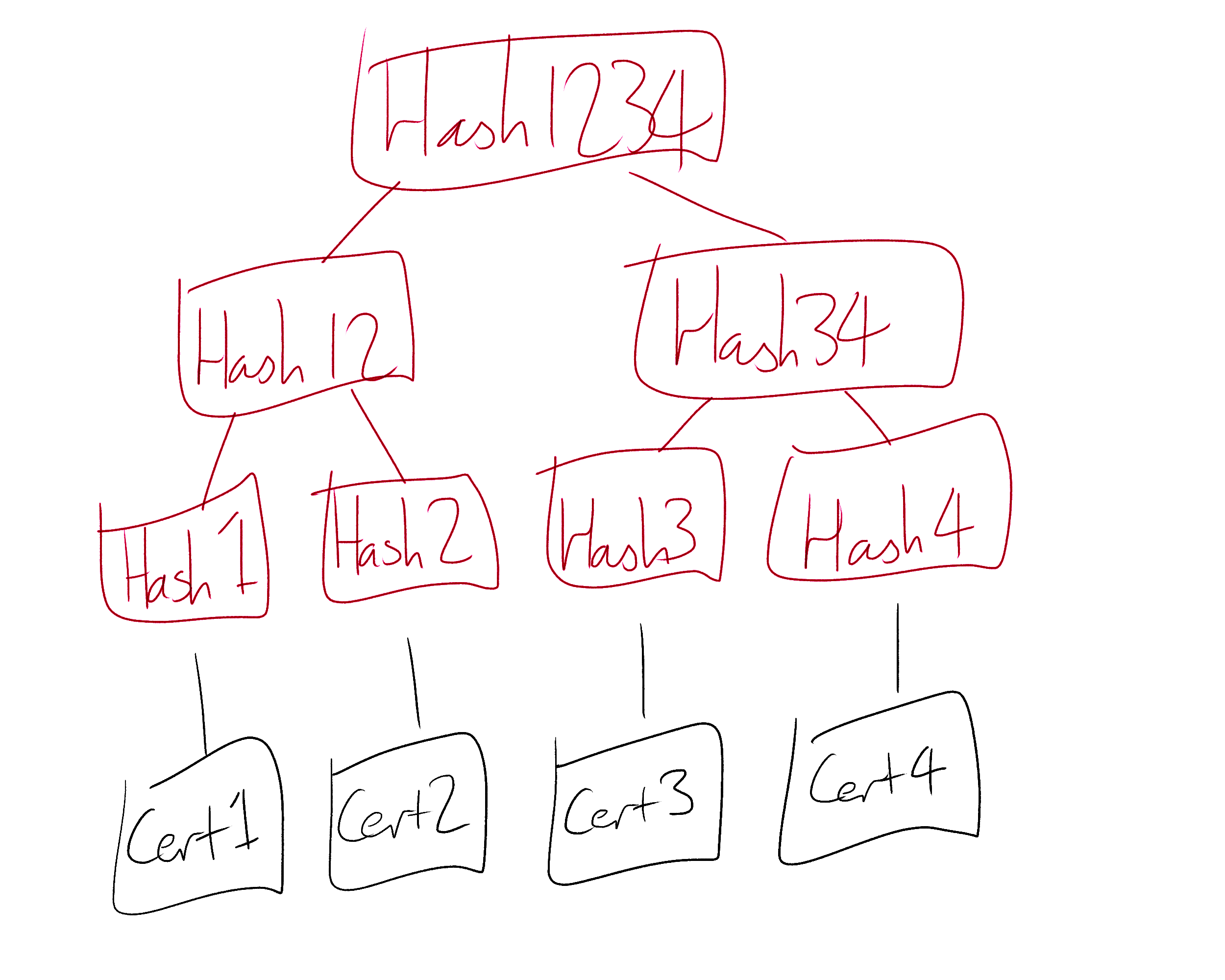

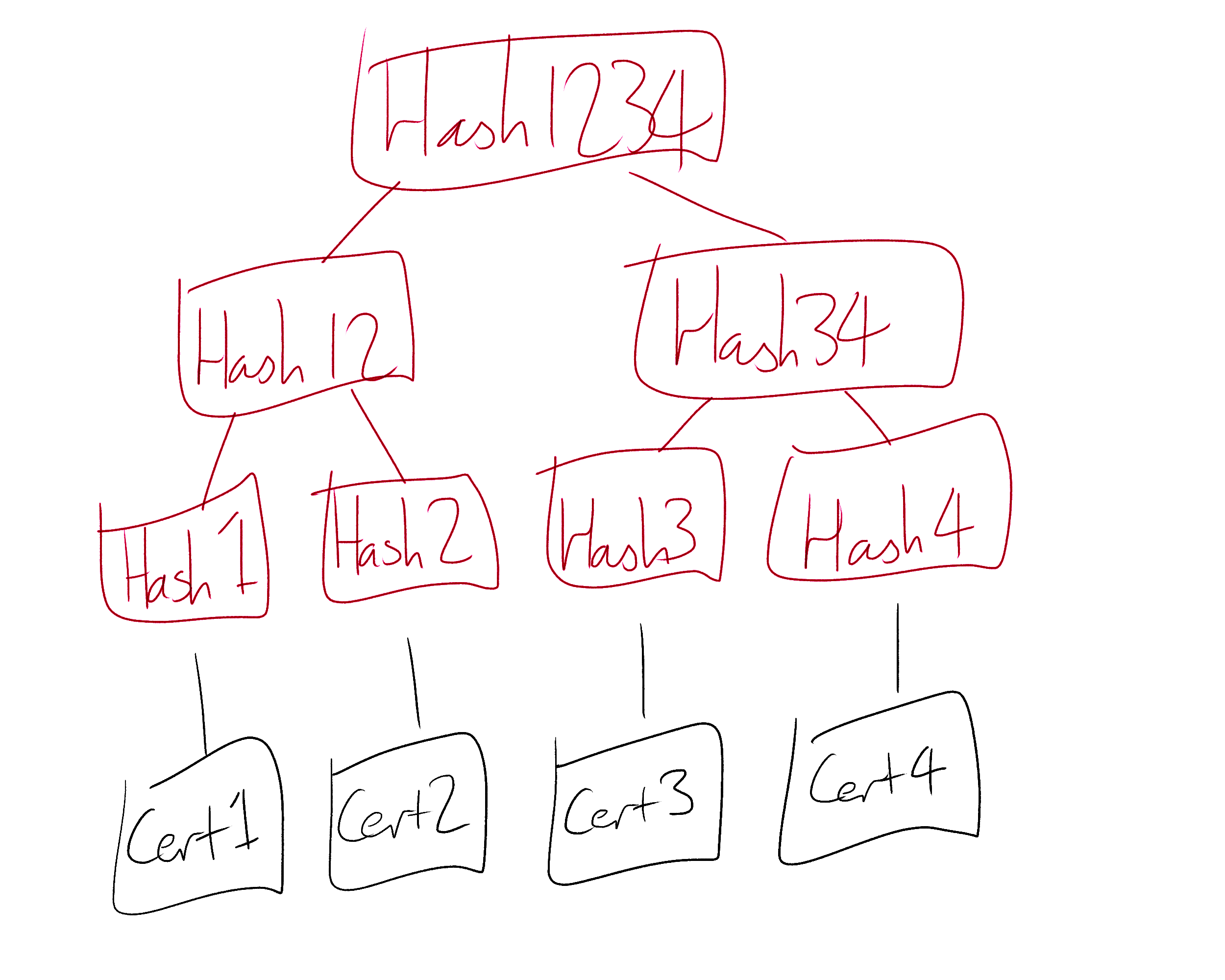

It is important that the CTLs are accurate and immutable. It should not be possible for a CTL operator to remove a certificate from their log, or to rewrite history to post-date additional certificates. CTL operators prove that their CTLs are immutable and append-only by storing them as a Merkle Tree, the same data structure behind most blockchains. A Merkle Tree is a tree in which each node contains a cryptographic hash of the contents of its children. If a child were removed or added then the hashes of a significant portion of the tree would need to be recomputed in order for the tree to remain valid. Such a change would be quickly noticed by the organizations watching and verifying the CTL, and the CTL is therefore protected against being tampered with by its operator.

There are actually quite a lot of people watching the watchmen. The final PKI component that we will look at - the CAA record - helps CAs watch themselves.

Certificate Authority Authorization

One purpose of the PKI system is to make incompetence as unprofitable as possible for CAs. The more visibility the rest of the world has into the actions of a CA, the more effort the CA is forced to spend on making sure that all of these actions are correct.

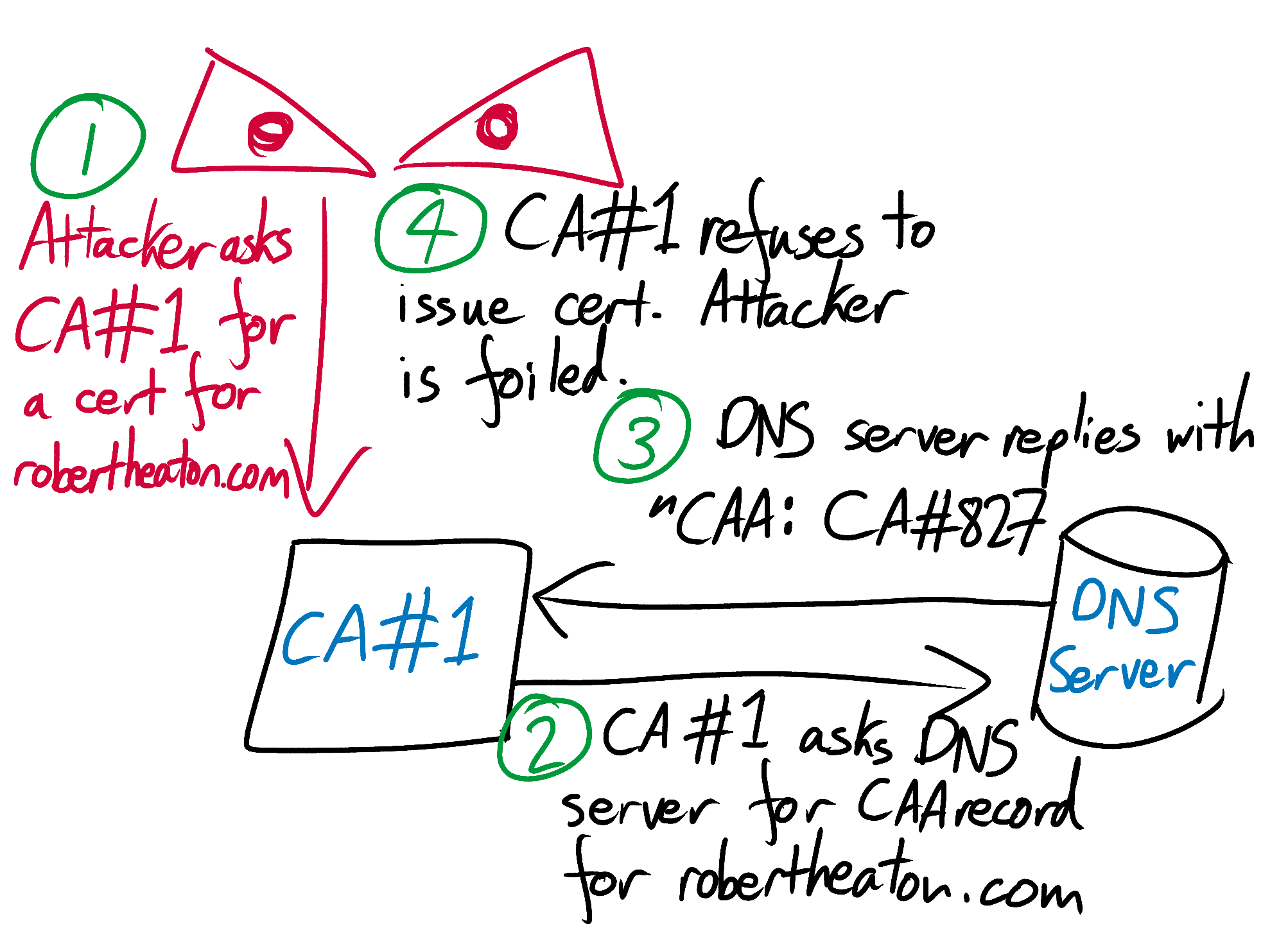

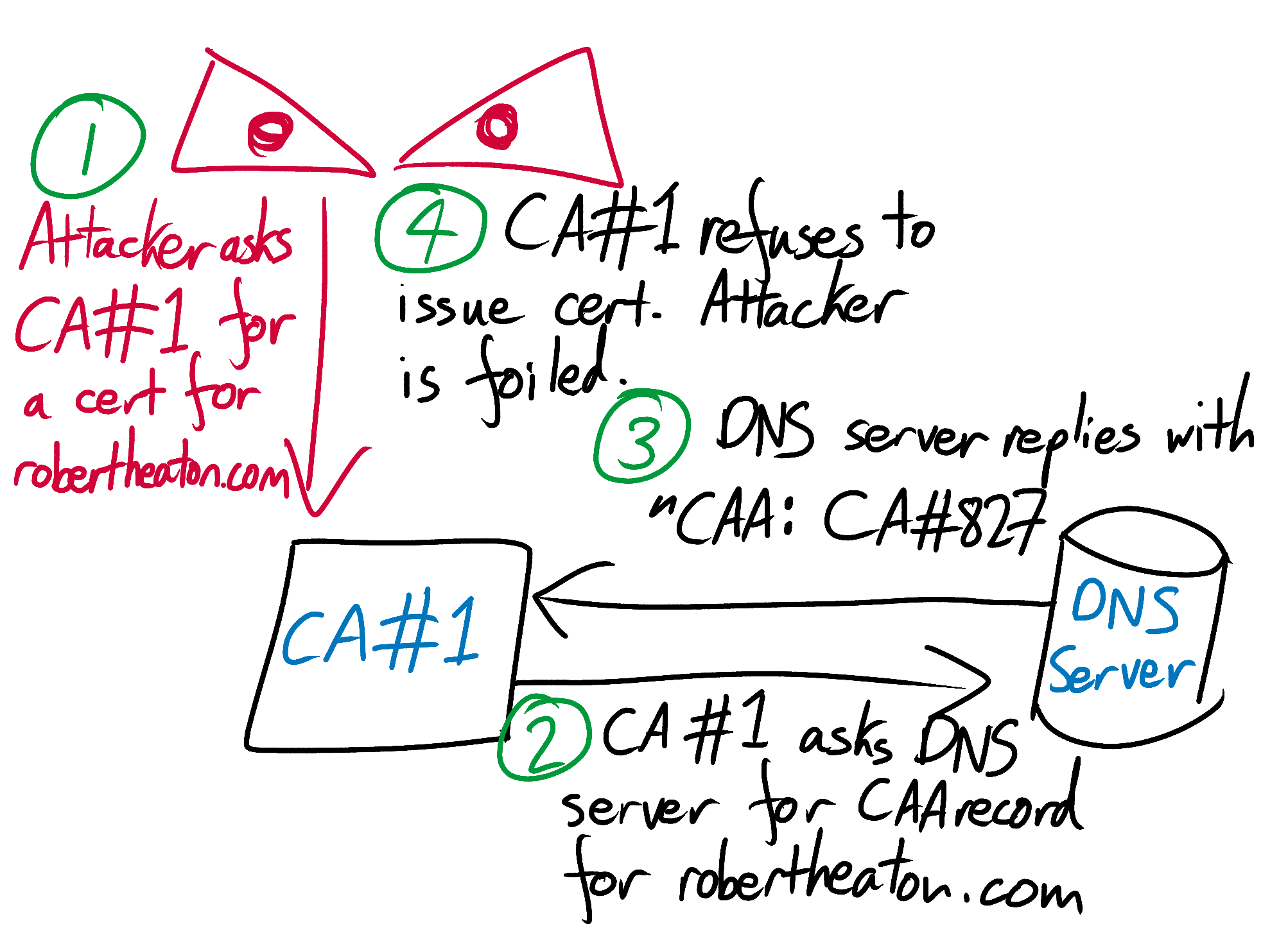

Domain owners are also highly incentivized to help CAs in their quest to avoid certificate mis-issuance. The consequences to a domain owner of a mis-issued certificate are somewhere between many hours of tedious hassle and a hideous data breach. Domain owners can help CAs avoid mis-issuance by setting a Certificate Authority Authorization (CAA) DNS record.

A domain’s CAA record lists the CAs that are allowed to issue certificates for the domain. If a CA is asked to generate a certificate for a domain, it should first check that domain’s CAA record. If the CA does not see itself in that record, it should assume that the customer is up to no good and decline to issue them a certificate. Once again, there is no way of verifying that a CA actually checks the CAA record or that they abide by it, but it is nonetheless a smart and simple way to reduce the attack surface and number of opportunities for unintended foolishness.

In conclusion

Alice and Bob live in the world of the HTTPS introduction. Alice has a TLS certificate issued by a reputable Certificate Authority. So does Bob. Alice keeps her private key safe. Bob does too. Alice and Bob use their certificates to verify each other’s identities and encrypt their communication. Despite the best efforts of Eve and all of the other attackers that live in Alice and Bob’s world, the mathematics of TLS keeps their communication completely safe.

The real world is much messier. Sometimes Certificate Authorities screw up. Sometimes private keys get compromised. And sometimes even the systems that are meant to alert people when these things happen are interfered with. None of these problems affect the world of the HTTPS introduction, but the real world is plagued by them.

TLS promises the inhabitants of any world extremely secure channels of communication. But these promises would remain purely theoretical if it weren’t for robust Public Key Infrastructure. TLS provides security on an insecure network. PKI provides security on an insecure world.

In cryptography, trust is mathematically provable. Everything else is just faith.

When you begin reading any introductory explanation of HTTPS, you are quickly whisked away to an alien planet inhabited by a savage society. On this world the entire population knows at least the basics of offensive computer networking, and coffee shop wi-fi connections are overflowing with attackers trying to steal each others’ Facebook passwords. Desperately holding these attackers at bay are nothing more than the raw power of HTTPS and a handful of trusted Certificate Authorities (CAs) run by incorruptible treefolk who live in the mountains.

The world of the HTTPS introduction makes no claims to reality. It exists only to highlight how incredible it is that an attacker can capture every single packet of HTTPS data that your browser exchanges with Facebook, and yet still have no idea what your password is. It shows just how powerful a system can be when you combine computers with incorruptible treefolk who live in the mountains, and how even just a tiny bit of total, no-questions-asked faith in a central authority can go a long way.

In the real world there’s no such thing as incorruptible treefolk, and there’s no such thing as no-questions-asked faith in a central authority that doesn’t also quickly wreck civilization. But the real world has still managed to piece together a very serviceable public-key cryptography system by patching over the holes and omissions and naivety of the introductory world with a tartan of secondary systems known collectively as “Public Key Infrastructure” (PKI).

PKI is neither perfect nor particularly elegant, but it still does a admirable job of coping with a wide range of real world complications. In this essay we’re going to look at three such complications. We’ll see how PKI addresses the facts that 1) your own private key might not stay private; 2) your Certificate Authority’s private key might not stay private; and 3) Certificate Authorities are not actually staffed exclusively by incorruptible treefolk who live in the mountains.

None of these complications affect the fundamental algorithms of public-key cryptography. Elliptic curve Diffie–Hellman is just as valid in the real world as it ever was in the world of the HTTPS introduction. If a message appears to be signed by Alice’s private key then we can still be certain that whoever signed it really is in possession of said key. However, in the real world, we have to take extremely seriously the possibility that this person might not have been Alice. We have to go to some quite extreme, fiddly, and fascinating lengths to build up enough faith to conclude that it probably was.

Complication 1: Your private key may not stay private

Your private key is just a file on a server. Files on servers get stolen all the time - just ask Uber, Equifax, Facebook, Target, Yahoo, and the DNC. Even worse, your private key is needed for negotiating every single TLS connection that is made with your servers, and is therefore in constant use. It can’t simply be stashed away inside a lockbox inside a bank vault and never touched.

You can take steps to keep your private key safe. For example, you can do all of your TLS connection negotiation on dedicated “TLS-termination” servers. These servers’ only job is decryption, and they are the only machines in your fleet that contain a copy of your private key. Once they have decrypted an HTTPS request, they forward it on to other servers to execute your business logic. Since the TLS-termination servers have already decrypted the request, these business logic servers do not need access to your private key.

This limits the number of machines with access to your private key, and means that you can lock down access to the TLS-termination servers extremely aggressively. They can be isolated from the rest of your server fleet, and access to them can be limited to a very small set of your employees. They can be watched by particularly sensitive monitoring, and touched only with a particularly heightened level of paranoia.

Plenty of things can still go wrong, and private keys can still be compromised. If this happens to you, an attacker in possession of your private key will be able to snoop on your users’ encrypted traffic with your website, or to simply impersonate your servers wholesale. You therefore need to be able to quickly notify the world that your key has been compromised and that everyone should stop having faith in your certificate. You need to be able to revoke your certificate.

Certificate revocation

A TLS certificate is an almost entirely self-contained passport. Its signature can be verified using nothing more than mathematics and a copy of all of the other certificates in its chain of trust (see below), with no need to talk to any outside, central authority.

Since TLS was designed without a central verification authority, it was also designed without a central “un-verification” authority. If your private key gets compromised then this doesn’t somehow stop the mathematics that went into its signature from being correct. Anyone who has access to your key can do a perfect cryptographic impression of you.

Un-verification, or “certificate revocation”, is challenging, and has been for decades. The first attempt at a process for disavowing certificates was the Certificate Revocation List (CRL) system. A CRL is a monolithic list of revoked certificates, maintained by a CA. When a certificate owner wants to revoke a certificate (perhaps because they believe it has been compromised), they inform CRL operators, who add this revocation to their lists. When a browser wants to know whether a mathematically valid certificate is still faith-worthy, it checks the certificate against a CRL. If the browser finds the certificate on the CRL then it knows that the certificate has been disavowed by its owner. The browser can calmly freak out and drop the connection.

The CRL process does work, and is in principle quite reasonable. However, CRLs are not updated frequently, and as the number of revoked certificates grows bigger and bigger, downloading and checking a CRL becomes slower and slower and less and less practical. On top of this, if a browser is unable to talk to a CRL server then it suddenly has no good options. It could count the verification as failed and refuse to continue making the connection. But this would prevent all users from accessing the affected domain, even though there is probably no actual security problem. It could count the verification as successful, and proceed as normal. But this would mean that an attacker could disable CRL checks entirely by blocking a victim’s network connection to a CRL server, at the time when these checks were needed the most.

The Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP) is an attempt to scale certificate revocation. Instead of asking a CRL server for the entire list of revoked certificates, a browser asks a certificate’s designated OCSP server (specified on the certificate itself) the simple question “has certificate X been revoked?” The server quickly replies “yes” or “no”, and the browser proceeds accordingly.

Since an OCSP check doesn’t require downloading a huge list of revoked certificates, it is much speedier and more lightweight than a CRL check. However, vanilla OCSP still has no good answer to the question of what to do when the OCSP server is down.

Happily, the problem of the missing OCSP server is addressed by the next iteration of OCSP: OCSP-stapling. In OCSP-stapling, it is the website server’s responsibility to query the OCSP server to check if its own certificate is still valid. The OCSP server checks its revocation lists, and if the certificate is still valid then it sends the website server back a signed confirmation of this fact. The website server attaches or “staples” this confirmation onto its certificate, and presents this augmented certificate to browsers.

Browsers can verify that the certificate’s stapled validation is legitimate and has been signed by the OCSP server. If the validation checks out, browsers can take it as assurance that the certificate has not yet been revoked. The validation expires after a short period of time, typically 24 hours, so the website operator must keep re-validating and re-stapling its certificate. If the certificate ever becomes revoked, the OCSP server will start refusing to provide new validations. Without a recent, signed OCSP confirmation, clients will refuse to trust the certificate. Since OCSP servers sign their validations using their own private keys, attackers cannot trick browsers into accepting revoked certificates by faking and stapling their own OCSP attestations.

OCSP-stapling is a relatively new innovation, and for now is only enabled for certificates with the Must-Staple flag set to true. Certificates without this flag set do not perform or staple OCSP validations, but their Must-Staple flag tells clients that this is OK.

Certificate revocation is a crucial tool for responding to key compromises. However, you can only revoke your certificate if you know that you’ve been hit. Sadly, sometimes you won’t. But you can reduce the impact of even an undiscovered theft of your private key by frequently expiring and rotating your TLS certificates.

Key rotation

Your certificate’s expiration date is recorded in a field on the certificate. After its expiry date, browsers will consider it just as untrustworthy as a certificate that is unsigned or clearly forged. If an attacker steals the private key for a certificate that expires in 5 years time, then that’s 5 years of future traffic to your website that they can decrypt if they can keep their breach undetected. If they silently steal the private key for a certificate that expires in 3 months then that’s still very bad, but at least in 3 months time their fun will automatically expire.

Setting short expiry periods and frequently rotating your certificates can therefore reduce the fallout of even an undiscovered key compromise. Doing so does require you to go to the effort of regularly replacing your certificates, but can be made very straightforward with the right tools.

Complication 2: A CA’s private key may not stay private

If an attacker steals your private key then they can impersonate you. But if they steal the private key of a CA then they can impersonate anyone. CAs take their own steps to prevent this from happening, and to mitigate the fallout if it ever does.

There are around 60 Root CAs whose certificates are hardcoded into browsers’ trust stores. If a Root CA’s certificate ever needed to be revoked then that CA would instantly lose the source of all its power. All of the certificates it had ever signed would be invalidated, and it would be unable to sign any new certificates until a new version of the browser was released containing a new, uncompromised, hardcoded certificate.

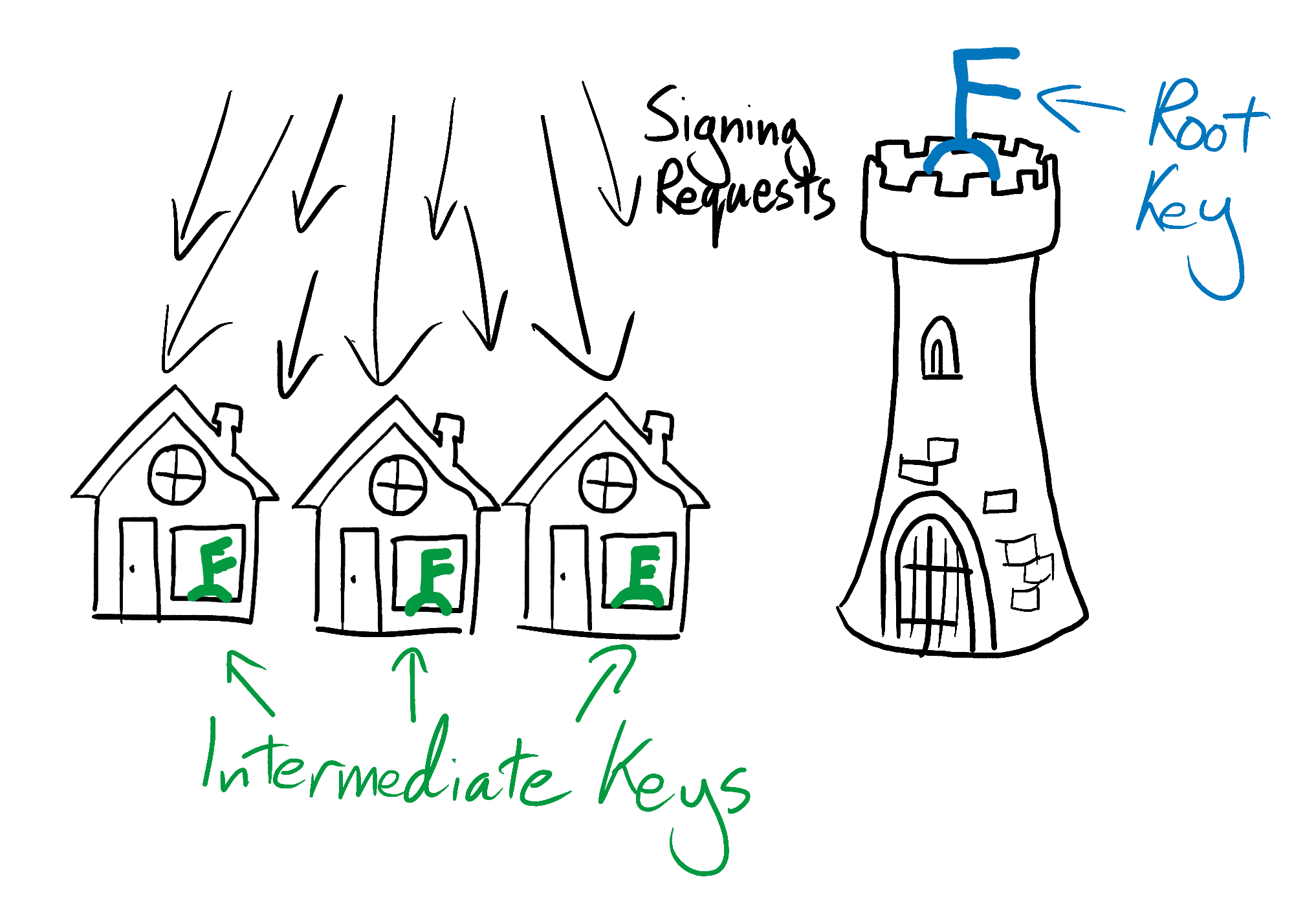

A CA can reduce the consequences of a breach of its root private key by delegating some or all of their root key’s power to an “intermediate CA”. It can do this by using its root key to sign an intermediate CA certificate, and using this intermediate CA certificate to sign its customers’ certificates. When a browser comes to check the validity of one of these certificates, it will see that it was signed by the intermediate CA, and that the intermediate’s certificate was signed by a Root CA. The browser has faith in the Root CA, and it sees that the Root CA has faith in the intermediate CA because it signed the intermediate CA’s certificate. The browser therefore trusts the customer’s certificate - any friend of Root’s is a friend of mine.

To keep their precious secrets safe, CAs typically don’t use their root keys for day-to-day signing. Instead they issue themselves with intermediate CA certificates, signed by their root key. They use these intermediate certificates for signing their customers’ certificates, and keep their root key completely locked down in a specialized, hardened machine called a hardware security module (HSM). An HSM swallows the key and makes it close to impossible for anyone to ever retrieve it again, even if they have physical access to the machine and a large suite of power tools. However, it does this in such a way that it can still use the key to sign certificates. On the rare occasions when the root private key is needed to sign a message, the HSM can still read the message and produce a signature. Since the root key is rarely used and is kept deep inside the HSM’s reinforced belly, it is very unlikely to be compromised.

Make no mistake; if the key for a workaday intermediate certificate were stolen then this would still be spectacularly bad. To mitigate the damage, the afflicted organization would have to revoke the compromised intermediate certificate. All of the certificates signed by it would be invalidated, and would cease to be accepted by browsers.

However, instead of having to wait for a new browser release before being able to sign keys again, the CA would be able to go to its almighty, divine, uncompromised root key and ask it to sign a new, intermediate CA certificate. The organization would be able use this new intermediate certificate to reissue all the certificates that had been issued by the compromised intermediate certificate. Whether anyone should want a reissued certificate from a CA that had been breached in this way is a separate question.

Complication 3. The CAs that you trust to do the right thing will not always do the right thing

Remember - in cryptography, trust is mathematically provable. Everything else is faith.

Judeo-Christian God understood this difference. He didn’t sign the Bible with his private key. That would be trust, not faith. You can audit God and build a plausible case for faith. You can read the unsigned Bible, make allowances for the bits that have aged poorly, and talk to your priest and rabbi about the bits that have aged really really poorly. But after that you’ve still got to have pure faith that the voice you think you hear at night really is God, and not your deep desire for there to be more to life than this.

You can audit Certificate Authorities too, or more likely read an audit that someone else has done, or even more likely have faith that someone somewhere has done an audit and that someone else has read it. You can read the Wikipedia page on TLS and skim the proofs of why factoring large numbers is difficult. But at a certain point you’ve got to have not-entirely-proven faith that the squishy, human bits of the system are working just as well as the cryptography. I trust that I am talking to someone with access to facebook.com’s private key. I have nothing more than faith that Facebook hasn’t had their private key stolen.

If you don’t have faith in Judeo-Christian God then you probably won’t get invited to the church summer picnic, and depending on who turns out to be right you might burn in hell for all eternity. But if you don’t have faith in HTTPS then you can’t use the internet. So whenever end-users like you or I open a new tab, we place our faith in our browser to keep us safe and secure. Our browser vendor does a lot of this work on its own. It makes sure that our browser’s code is fortified with vitamins and stack safety, and that its JavaScript implementation conforms to the ECMA spec. But our browser vendor delegates our faith in identity verification to the CAs whose public keys it hardcodes into its trust store.

We can break down this faith into two parts. The first, which we have discussed already, is that the CA will keep its signing keys safe from compromise. The second is that the CA itself won’t use these keys to do anything stupid or malicious.

Root CAs have the absolute power to sign certificates for any domain. There’s no cryptography preventing them from deliberately or accidentally abusing this power; only process, monitoring, and the threat of being removed from browser root trust stores. Our browser vendor ensures that each root CA is worthy of faith through checks and audits of its processes. If any CA is found lacking then it may be expelled from the browser’s list of root authorities, instantly and completely destroying that CA’s business.

Indeed, Symantec’s CA operation was recently untrusted by Chrome and other major browsers, in part because it had been repeatedly mis-issuing certificates for domains to people who did not control them. The browsers took this drastic action because the whole and sole point of a CA is that they can be relied on to only ever issue certificates to the right people.

The standards that CAs should follow are agreed upon at the Certificate Authority/Browser (CA/B) Forum. For example, whenever a customer asks a CA to sign a certificate for a domain, the CA is first supposed to confirm that the customer really does own the domain. 2 of the most straightforward and easily automated methods are those used by Let’s Encrypt. Let’s Encrypt requires their customers to either provision a specific DNS record for the domain they are requesting a certificate for, or to place a specially formatted file at a specific path (eg. example.com/asdkjnsad13p87gdbjhsdjbhiup). Neither of these challenges should be completable without direct control over a domain. If a Let’s Encrypt customer is able to complete one of them, Let’s Encrypt takes this as proof that this customer really does control the domain, and issues them with the certificate that they requested.

But later, when a browser is inspecting this certificate and deciding whether to have faith in it, there is no way for it to know for certain whether the CA that signed it really did properly verify the domain’s ownership. Lax CA domain verification can and does result in the issuance of certificates for domains to customers who don’t control them. This undermines the very foundation of public-key cryptography. To forcefully encourage CAs to improve, and to more rapidly uncover those times when they screw up, PKI has recently grown another limb: Certificate Transparency Logs.

Certificate Transparency Logs

Until recently, domain owners had no systematic way of finding out if a CA had mis-issued a certificate for their domain. The first they knew about the problem could easily be when their users began getting owned. There was no announcement when a new certificate was issued, and no databases of issued certificates that domain owners could inspect.

To try to uncover mis-issued certificates faster and more consistently, Google has spearheaded the creation of a system called the Certificate Transparency Log (CTL). CTLs makes it easy for domain owners to find out when a CA has issued and signed a certificate for their domain. They make the previously silent process of certificate issuance much noisier and therefore more easily observable.

A CTL is a public log of public certificates. There are many CTLs: Google runs several, Comodo runs one, and some guy runs one from behind a sofa in London. When a CA signs a new certificate for a customer, the CA is required to submit it to at least 2 CTLs. When they do, the operator of each CTL adds the certificate to their public log and sends the CA back a signature that says “I, Ms. C.T.L. Operator, have received this certificate and will add it to my log.” The CA appends these signatures to the original certificate, since they prove that it has met its responsibility to submit it to 2 CTLs. The CA then gives the signed and provably logged certificate to its customer.

Domain owners can now monitor CTLs for newly issued certificates on their domain that they don’t recognize. They can do this either by downloading the (completely public) data and sifting through it themselves, or by using a service like crt.sh to sift through it for them. If they see a certificate that they don’t recognize, they can freak out, try to get it revoked, and try to get the CA that signed it into trouble.

CTLs do have unfortunate side-effects. Services like crt.sh are useful tools not only for domain owners, but for attackers too. Attackers can search crt.sh for all certificates for subdomains of a particular website, and can scour this list for less well-known and perhaps less protected targets. For example, I’m sure that www.dewey-lfs.vip.facebook.com is perfectly well-secured, whatever it is, but I bet that it’s not watched quite as closely as the main facebook.com infrastructure.

Since CTLs mean more work and more scrutiny for CAs, we might expect them to decline or accidentally forget to play along. To force CAs to comply, browsers refuse to trust TLS certificates without at least 2 valid signatures from CTL operators. If a CA tries to evade scrutiny by not submitting a new certificate to 2 CTLs, they will not have 2 valid CTL signatures that they can append to it. Without these signatures the certificate will not be trusted by browsers and so will be useless.

It is important that the CTLs are accurate and immutable. It should not be possible for a CTL operator to remove a certificate from their log, or to rewrite history to post-date additional certificates. CTL operators prove that their CTLs are immutable and append-only by storing them as a Merkle Tree, the same data structure behind most blockchains. A Merkle Tree is a tree in which each node contains a cryptographic hash of the contents of its children. If a child were removed or added then the hashes of a significant portion of the tree would need to be recomputed in order for the tree to remain valid. Such a change would be quickly noticed by the organizations watching and verifying the CTL, and the CTL is therefore protected against being tampered with by its operator.

There are actually quite a lot of people watching the watchmen. The final PKI component that we will look at - the CAA record - helps CAs watch themselves.

Certificate Authority Authorization

One purpose of the PKI system is to make incompetence as unprofitable as possible for CAs. The more visibility the rest of the world has into the actions of a CA, the more effort the CA is forced to spend on making sure that all of these actions are correct.

Domain owners are also highly incentivized to help CAs in their quest to avoid certificate mis-issuance. The consequences to a domain owner of a mis-issued certificate are somewhere between many hours of tedious hassle and a hideous data breach. Domain owners can help CAs avoid mis-issuance by setting a Certificate Authority Authorization (CAA) DNS record.

A domain’s CAA record lists the CAs that are allowed to issue certificates for the domain. If a CA is asked to generate a certificate for a domain, it should first check that domain’s CAA record. If the CA does not see itself in that record, it should assume that the customer is up to no good and decline to issue them a certificate. Once again, there is no way of verifying that a CA actually checks the CAA record or that they abide by it, but it is nonetheless a smart and simple way to reduce the attack surface and number of opportunities for unintended foolishness.

In conclusion

Alice and Bob live in the world of the HTTPS introduction. Alice has a TLS certificate issued by a reputable Certificate Authority. So does Bob. Alice keeps her private key safe. Bob does too. Alice and Bob use their certificates to verify each other’s identities and encrypt their communication. Despite the best efforts of Eve and all of the other attackers that live in Alice and Bob’s world, the mathematics of TLS keeps their communication completely safe.

The real world is much messier. Sometimes Certificate Authorities screw up. Sometimes private keys get compromised. And sometimes even the systems that are meant to alert people when these things happen are interfered with. None of these problems affect the world of the HTTPS introduction, but the real world is plagued by them.

TLS promises the inhabitants of any world extremely secure channels of communication. But these promises would remain purely theoretical if it weren’t for robust Public Key Infrastructure. TLS provides security on an insecure network. PKI provides security on an insecure world.