Introducing Afl-Ruby: fuzz your Ruby programs using afl

16 Feb 2019

American Fuzzy Lop (afl) is a popular fuzzer, traditionally used to find bugs in C and C++ code. python-afl and aflgo have adapted afl for use with python and go, and now afl-ruby (written by Richo Healey, with contributions from myself) allows you to use afl to fuzz Ruby programs too.

Here’s how it works.

Usage

1. Write a harness for your code

Fuzzing any piece of code requires a harness program that can be invoked by afl. You’ll need to write a harness that:

- Initializes the afl forkserver using

AFL.init

- Wraps the fuzzable piece of your harness in an

AFL.with_exceptions_as_crashes { ... } block

- Reads bytes from

stdin and uses them as input to your program

For example:

def next_byte

$stdin.read(1)

end

def c; r() if next_byte() == 'r'; end

def r; s() if next_byte() == 's'; end

def s; h() if next_byte() == 'h'; end

def h; raise "Crashed"; end

require 'afl'

AFL.init unless ENV['NO_AFL']

AFL.with_exceptions_as_crashes do

c() if next_byte() == 'c'

exit!(0)

end

2. Patch afl

Next you’ll need to apply a tiny patch to afl itself - for quick instructions see the afl-ruby README. The patch comments out afl’s check that the target you give it has been instrumented properly. We are still going to instrument your code, but in a different way to how afl normally does it. See below for more details.

3. Build the afl-ruby gem

Afl-ruby is not yet available on Ruby gems, so you’ll need to clone and build it yourself. This should be straightforward; once again the README has instructions.

4. Fuzz your program as normal using afl-fuzz

/path/to/afl/afl-fuzz \

-i work/input \

-o work/output \

-- /usr/bin/ruby example/harness.rb

Afl finds the crash in the above example program in about 30 seconds on my laptop. Inspecting the queue/ directory shows the points along the way at which afl realized it had found an interesting new branch.

Technical discussion

Afl was originally written to be run against C and C++ targets. In order to understand how it can it be adapted for use with Ruby, Python, and go, we’ll need to spend a few paragraphs understanding how afl works.

Afl observes how different test cases change the execution path of your program, and uses this information to skillfully generate further interesting test cases. For example, afl might notice that if it twiddles the 10th byte of a test case just so then it triggers a new branch of a switch-statement inside your program. It will remember this useful nugget, and use it to design new test cases that continue to explore this uncharted section of your program.

The execution path of your program is not available to afl by default. In order to get this information, afl needs to augment your program with additional instrumentation that records (a representative sample of) the files and line numbers that get executed.

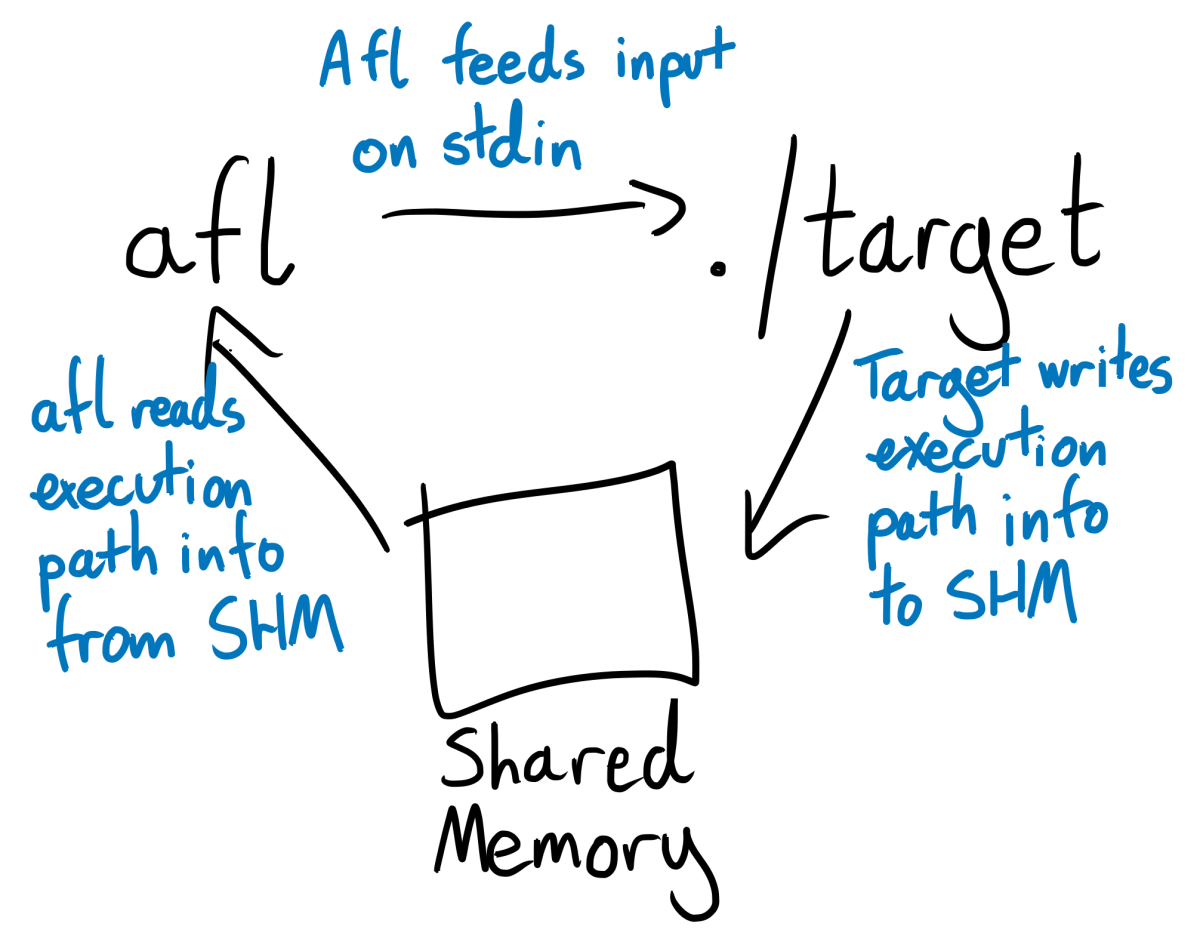

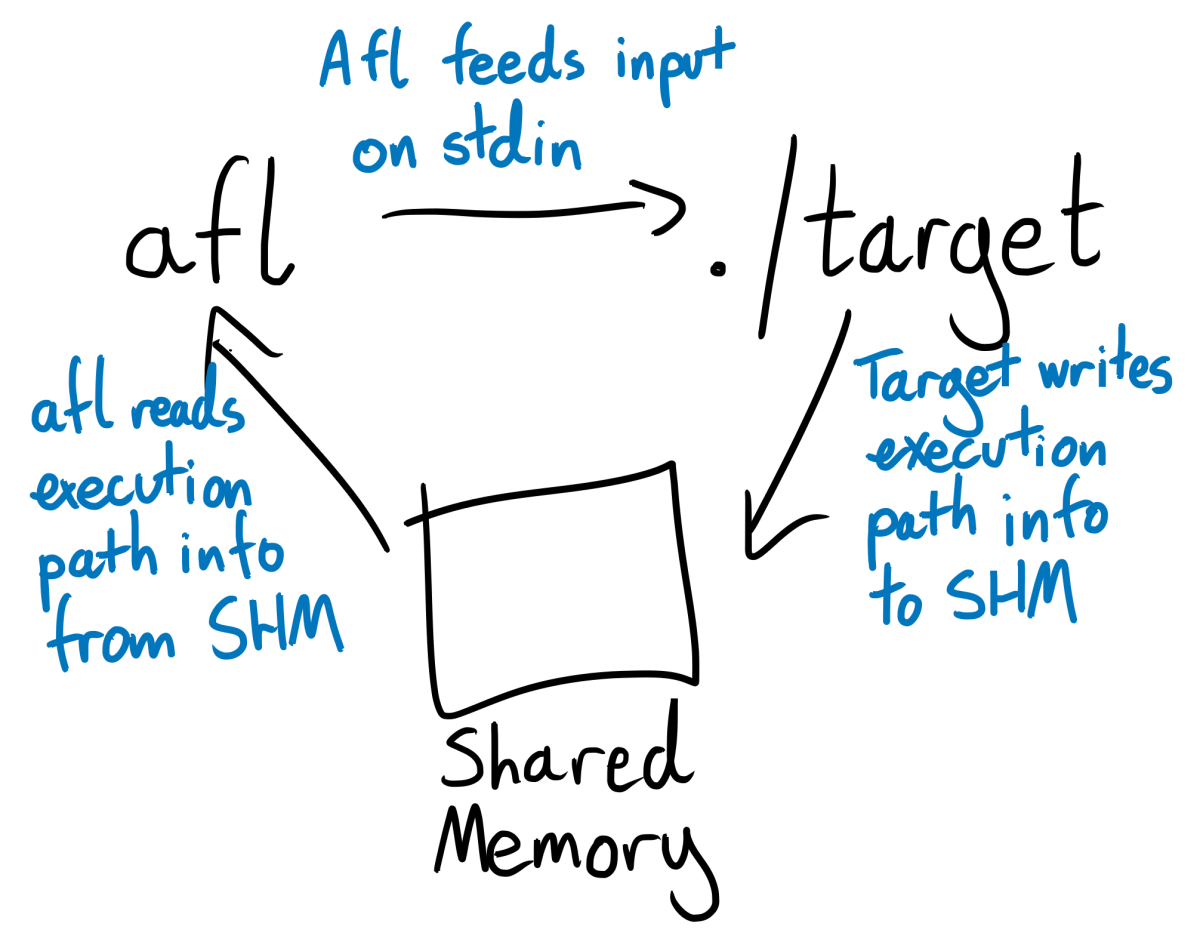

Afl instruments C and C++ programs by requiring them to be compiled with one of its custom compilers (afl-clang, afl-gcc, afl-clang-fast, or their C++ equivalents). These custom compilers compile your program as normal, but also inject afl’s instrumentation. Then, whenever your program executes an instrumented line of code, it also writes information about the line’s number and filename to a shared memory segment. This memory segment is shared with the afl process that is fuzzing your program, which means that the afl can see how different test case affects the internal behavior of your program.

A crucial consequence of this approach to instrumentation is that the afl-fuzz command doesn’t actually need to “know” anything about C or C++. When invoking afl-fuzz, you pass afl the shell command that it should use to invoke your program. afl-fuzz then runs your program by shelling out to it, feeds your program test cases via stdin, and reads information about your program’s execution path directly from its shared memory segment. These are all completely language agnostic processes. Since afl doesn’t know or care how data gets into the shared memory segment, we can adapt it to work with a new language by re-implementing its instrumentation in that language.

This typically requires a little rooting around in internals, searching for tools that allow us to hooking into the new language’s compiler or interpreter. Ruby has TracePoint, a module in the standard library that allows us to register callbacks that run whenever the Ruby interpreter performs a particular action, such as running a line of code, entering a function, or returning from one. Afl-ruby uses TracePoint to register a callback that writes out information about executed files and line numbers to afl’s shared memory segment.

For now afl-ruby only invokes this callback when a new function is entered. This felt like a good balance between high-fidelity recording and overwhelming afl with too much detail that it doesn’t need. It’s certainly possible that a more frequent; infrequent; or nuanced scheme would produce better results. More research required.

Differences and similarities between fuzzing Ruby and C

There are two main differences between the businesses of fuzzing Ruby and C programs. The first is in the bugclasses that you can expect or hope to find. Most of the bugs that fuzzing shakes out of low-level programs are related to memory-mismanagement, such as overflows, underflows, and segfaults. This is probably because fuzzers are more likely than humans to hammer programs with 1024 letter “A”s followed by a null byte, and so are more likely to find any bugs that doing so might reveal.

Ruby is a higher-level language than both C and C++, and so is less vulnerable to this kind of low-level goof. That doesn’t mean there aren’t plenty of errors waiting to be found though. Can users make your program throw an exception? Is it possible for a nil sneak into a place where a nil is not meant to be?

You’ll also likely want to make more use of property-based-testing-style assertions. These are business logic statements that should always be true for every execution of your program, for example “money in should always equal money out” or “non-admins should never perform an admin action”. After invoking the main body of your program, you can add if-statements to verify that these statements are indeed true. For example:

AFL.init

AFL.with_exceptions_as_crashes do

money_in, money_out = run_my_program()

if money_in != money_out

raise "Money in should always equal money out!"

end

end

lcamtuf, the creator of afl, discusses this approach briefly in the afl docs. It’s also possible that you made a pure programming error and allowed a nil to sneak into a place where a nil was never meant to be, but business-logic assertions are likely to be where you’ll find the juiciest bugs.

Second - Ruby is very slow, at least when compared to C and C++. Even the trivial example harness at the start of this post only reached 100 execs/second on my laptop, compared to C programs that comfortably hit one or two thousand. You can either wait longer for your results, or look into a distributed fuzzer like roving, also originally built by Richo Healey and developed further by me as part of my work at Stripe.

On the other hand, fuzzing Ruby and C programs still remain broadly similar endeavors. Traditional afl can improve its test case generation by using a user-supplied set of example inputs or dictionary of common tokens. These mechanisms still work with afl-ruby. All of the usual principles of writing good fuzzing harnesses still apply - stub out network calls and non-determinism, and try not to force the fuzzer to guess magic strings or checksums. Read the very clear and well-written afl docs.

Take afl-ruby for a spin, let us know what you find, and submit a PR if you have any improvements!

Thanks to Jakub Wilk for writing python-afl, on which much of afl-ruby is based. Thanks also to Richo Healey for writing the bulk of afl-ruby, and to Stripe for letting both Richo and I work on it on company time.

American Fuzzy Lop (afl) is a popular fuzzer, traditionally used to find bugs in C and C++ code. python-afl and aflgo have adapted afl for use with python and go, and now afl-ruby (written by Richo Healey, with contributions from myself) allows you to use afl to fuzz Ruby programs too.

Here’s how it works.

Usage

1. Write a harness for your code

Fuzzing any piece of code requires a harness program that can be invoked by afl. You’ll need to write a harness that:

- Initializes the afl forkserver using

AFL.init - Wraps the fuzzable piece of your harness in an

AFL.with_exceptions_as_crashes { ... }block - Reads bytes from

stdinand uses them as input to your program

For example:

def next_byte

$stdin.read(1)

end

def c; r() if next_byte() == 'r'; end

def r; s() if next_byte() == 's'; end

def s; h() if next_byte() == 'h'; end

def h; raise "Crashed"; end

require 'afl'

AFL.init unless ENV['NO_AFL']

AFL.with_exceptions_as_crashes do

c() if next_byte() == 'c'

exit!(0)

end

2. Patch afl

Next you’ll need to apply a tiny patch to afl itself - for quick instructions see the afl-ruby README. The patch comments out afl’s check that the target you give it has been instrumented properly. We are still going to instrument your code, but in a different way to how afl normally does it. See below for more details.

3. Build the afl-ruby gem

Afl-ruby is not yet available on Ruby gems, so you’ll need to clone and build it yourself. This should be straightforward; once again the README has instructions.

4. Fuzz your program as normal using afl-fuzz

/path/to/afl/afl-fuzz \

-i work/input \

-o work/output \

-- /usr/bin/ruby example/harness.rb

Afl finds the crash in the above example program in about 30 seconds on my laptop. Inspecting the queue/ directory shows the points along the way at which afl realized it had found an interesting new branch.

Technical discussion

Afl was originally written to be run against C and C++ targets. In order to understand how it can it be adapted for use with Ruby, Python, and go, we’ll need to spend a few paragraphs understanding how afl works.

Afl observes how different test cases change the execution path of your program, and uses this information to skillfully generate further interesting test cases. For example, afl might notice that if it twiddles the 10th byte of a test case just so then it triggers a new branch of a switch-statement inside your program. It will remember this useful nugget, and use it to design new test cases that continue to explore this uncharted section of your program.

The execution path of your program is not available to afl by default. In order to get this information, afl needs to augment your program with additional instrumentation that records (a representative sample of) the files and line numbers that get executed.

Afl instruments C and C++ programs by requiring them to be compiled with one of its custom compilers (afl-clang, afl-gcc, afl-clang-fast, or their C++ equivalents). These custom compilers compile your program as normal, but also inject afl’s instrumentation. Then, whenever your program executes an instrumented line of code, it also writes information about the line’s number and filename to a shared memory segment. This memory segment is shared with the afl process that is fuzzing your program, which means that the afl can see how different test case affects the internal behavior of your program.

A crucial consequence of this approach to instrumentation is that the afl-fuzz command doesn’t actually need to “know” anything about C or C++. When invoking afl-fuzz, you pass afl the shell command that it should use to invoke your program. afl-fuzz then runs your program by shelling out to it, feeds your program test cases via stdin, and reads information about your program’s execution path directly from its shared memory segment. These are all completely language agnostic processes. Since afl doesn’t know or care how data gets into the shared memory segment, we can adapt it to work with a new language by re-implementing its instrumentation in that language.

This typically requires a little rooting around in internals, searching for tools that allow us to hooking into the new language’s compiler or interpreter. Ruby has TracePoint, a module in the standard library that allows us to register callbacks that run whenever the Ruby interpreter performs a particular action, such as running a line of code, entering a function, or returning from one. Afl-ruby uses TracePoint to register a callback that writes out information about executed files and line numbers to afl’s shared memory segment.

For now afl-ruby only invokes this callback when a new function is entered. This felt like a good balance between high-fidelity recording and overwhelming afl with too much detail that it doesn’t need. It’s certainly possible that a more frequent; infrequent; or nuanced scheme would produce better results. More research required.

Differences and similarities between fuzzing Ruby and C

There are two main differences between the businesses of fuzzing Ruby and C programs. The first is in the bugclasses that you can expect or hope to find. Most of the bugs that fuzzing shakes out of low-level programs are related to memory-mismanagement, such as overflows, underflows, and segfaults. This is probably because fuzzers are more likely than humans to hammer programs with 1024 letter “A”s followed by a null byte, and so are more likely to find any bugs that doing so might reveal.

Ruby is a higher-level language than both C and C++, and so is less vulnerable to this kind of low-level goof. That doesn’t mean there aren’t plenty of errors waiting to be found though. Can users make your program throw an exception? Is it possible for a nil sneak into a place where a nil is not meant to be?

You’ll also likely want to make more use of property-based-testing-style assertions. These are business logic statements that should always be true for every execution of your program, for example “money in should always equal money out” or “non-admins should never perform an admin action”. After invoking the main body of your program, you can add if-statements to verify that these statements are indeed true. For example:

AFL.init

AFL.with_exceptions_as_crashes do

money_in, money_out = run_my_program()

if money_in != money_out

raise "Money in should always equal money out!"

end

end

lcamtuf, the creator of afl, discusses this approach briefly in the afl docs. It’s also possible that you made a pure programming error and allowed a nil to sneak into a place where a nil was never meant to be, but business-logic assertions are likely to be where you’ll find the juiciest bugs.

Second - Ruby is very slow, at least when compared to C and C++. Even the trivial example harness at the start of this post only reached 100 execs/second on my laptop, compared to C programs that comfortably hit one or two thousand. You can either wait longer for your results, or look into a distributed fuzzer like roving, also originally built by Richo Healey and developed further by me as part of my work at Stripe.

On the other hand, fuzzing Ruby and C programs still remain broadly similar endeavors. Traditional afl can improve its test case generation by using a user-supplied set of example inputs or dictionary of common tokens. These mechanisms still work with afl-ruby. All of the usual principles of writing good fuzzing harnesses still apply - stub out network calls and non-determinism, and try not to force the fuzzer to guess magic strings or checksums. Read the very clear and well-written afl docs.

Take afl-ruby for a spin, let us know what you find, and submit a PR if you have any improvements!

Thanks to Jakub Wilk for writing python-afl, on which much of afl-ruby is based. Thanks also to Richo Healey for writing the bulk of afl-ruby, and to Stripe for letting both Richo and I work on it on company time.