MinorMiner: we turn your kid's maths homework into Bitcoin

14 May 2025

Hello! Hello! Welcome, welcome. My name is Hobert Reaton, and I’m here in this shabby motel conference room to present you with yet another once-in-a-lifetime investment opportunity.

Look at this picture. Tell me what you see:

Do you see learning? Self-improvement? The future leaders of our country?

I’ll tell you what I see: wasted computing power.

Between the ages of 5 and 18, the average child in full-time education completes about 5 maths worksheets a week. Each worksheet has 20 questions. This means that over the course of their school career, every single one of our kids performs about 80,000 calculations.

At the moment we completely waste their work. A student figures out that 5+5=10 and 7x7=49. This motivates them; they’re energised by their success. But then what do we do with the fruits of their labour? Nothing! We throw the fruit away, to rot in the void. “We knew that already,” we tell our children. “Your ideas don’t matter.” Unlike the rest of society, I believe that kids deserve to feel appreciated. I believe that their achievements are valuable.

That’s why I founded MinorMiner.

What is MinorMiner?

MinorMiner is a platform that allows school-age children to monetise their maths homework by using it to mine Bitcoin. Yes, you heard me. We send children their homework, they crunch through it, and then together we transform their sweat into digital gold. This isn’t some rinky-dink incentive program where we bribe children to care about multiplication. Homework is the essential raw material that feeds our machine. We need these kids. No kids; no Bitcoin.

In order to understand the innovation that makes MinorMiner possible, we first need to understand how Bitcoin is mined today. Right now, people mine Bitcoin by using computers to solve complex mathematical puzzles. The puzzles look like this:

- Take the list of the Bitcoin transactions that have occurred since the last Bitcoin was mined. Check that they’re all correctly authorized and that none of them spend money that the creator doesn’t have.

- Choose a string of extra letters and numbers to add on to the end of this list (a nonce). This is your attempt to solve the puzzle.

- Pass the list and your extra characters through an extremely complex function called the SHA-256 hash function (technically you pass it through the function twice). The hash function chops and slices and spins and dices the input around, seemingly (but not actually) at random. At the end it spits out a number

- The puzzle that you’re trying to solve is: what combination of letters and numbers from step 2 cause the output from step 3 to be less than some small target number?

There’s no elegant way to solve these puzzles. The only thing for Bitcoin miners to do is to guess inputs to step 2, over and over and over again, until they find one that happens to satisfy the criteria in step 4. When a miner guesses a right answer we say that they’ve “mined” a new “block”. They attach their solution to the blockchain to show that they’ve verified the transactions in the block, and they’re rewarded with new bitcoin. Their work, along with a couple of extra steps that I’ve hand-waved over, ensures that the blockchain stays safe and secure.

However, it also requires an incredible amount of electricity - around 150TWh per year, or 1% of the world’s total energy consumption. What if there was a better, more efficient way to achieve the same thing?

This is where MinorMiner and school-aged children come in. “But Bitcoin mining sounds hard!” I hear you wail. “My child has only a rudimentary grasp of basic algorithms!” True, true - but the magic is that the children on our platform don’t need to know how to mine Bitcoin, and they won’t even know that they’re doing it. Our team has converted the SHA-256 hashing algorithm used by the bitcoin blockchain into a sequence of elementary arithmetic questions that even the dullest dullard can answer. Solving a blockchain puzzle used to require understanding and executing a SHA-256 hash. Now all it takes is skipping through a few trillion simple brainteasers.

5+3=?10*5=?Is 102 bigger than 67? (y/n)- And so on

The kids do these sums - we take care of the rest.

How does the MinorMiner platform work?

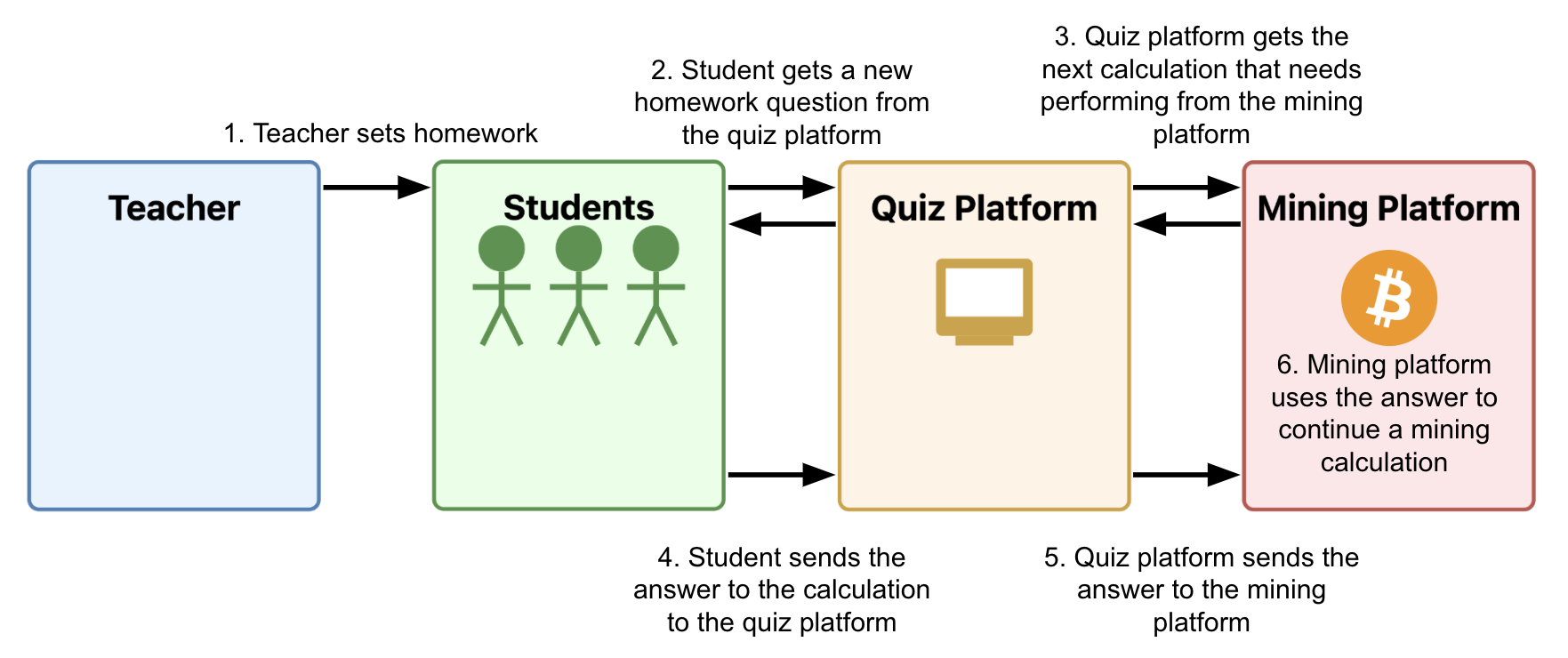

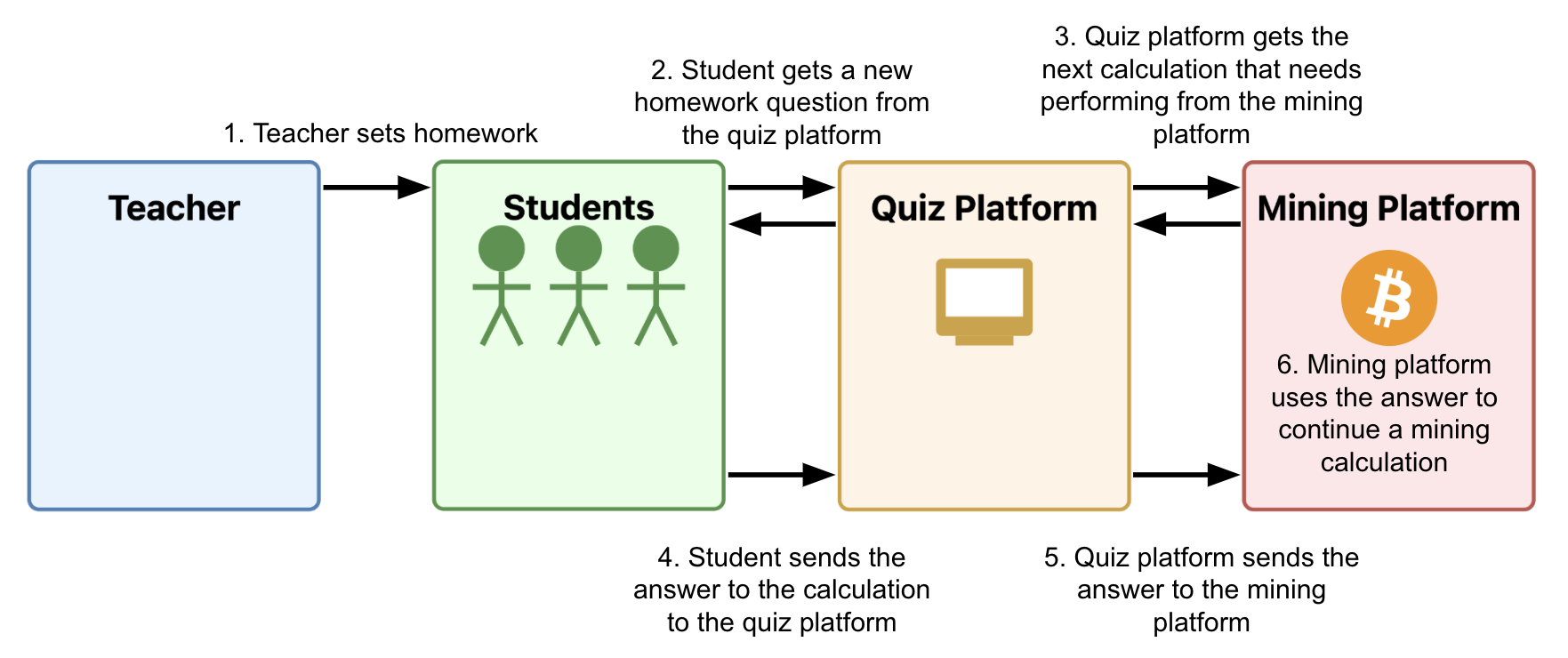

The heart of MinorMiner is a centralised system that manages our mining. The system decomposes a SHA-256 hash computation into simple arithmetic questions, and works out which of these questions need answering next. Simple enough - but how do we get the questions to the kids? Three words: online maths quizzes.

You see, MinorMiner also has a maths learning platform that we sell to schools all over the world. Our platform isn’t particularly good, but we give department heads a generous revenue share and so this tends not to matter. Once a teacher (or “distribution associate” as we like to call them) is set up on MinorMiner, they assign a quiz to their class as homework. In the evening their children (or “computation partners”) log into the MinorMiner portal and answer their quiz for the day, which consists of whatever questions our hashing system needs doing next. By way of compensation their distribution associate doesn’t give them a detention. We collect their answers and use them to continue calculating a hash. When one partner finishes their quiz, the next partner continues calculating from where they left off.

We have to be careful - a hash is a delicate thing. One tiny mistake in one tiny step and - poof! - the whole calculation is completely, irreversibly screwed. That’s why send each calculation to two separate computation partners. If their answers disagree then we escalate to a slightly older partner to adjudicate. We maintain a rating for each partner based on their accuracy. If their rating drops below 4.3 stars then they are invited to undergo additional training to help them get back to the standard expected for MinorMiner partners. If such improvement is not forthcoming then they are invited to seek maths education elsewhere.

Any questions so far? No? Then it’s time for me to show you our real technological breakthrough.

CUDAAAAGH

We write our mining code using a Python library called Centralized Underage Distributed Arithmetic - Automated Assignment And Group Hashing (CUDAAAAGH). CUDAAAAGH allows us to distribute any complex computation across an infinitely-scalable pool of computation partners. We’ve open-sourced it on GitHub and PyPi.

To use it, we run pip install CUDAAAAGH and then use its CUDAAAAGHInt class everywhere we would normally use Python’s standard integer type. Aside from that, we write all of our code as normal. When we execute our program, CUDAAAAGH automatically offloads any arithmetic computations to our network of computation partners, instead of burdening our own CPUs.

For example:

from CUDAAAAGH import CUDAAAAGHInt

x = CUDAAAAGHInt(5)

y = x + CUDAAAAGHInt(10)

# Behind the scenes, this sends the calculation "5+10" to a computation

# partner. Execution pauses until we receive an answer.

print(f"The answer is: {y}")

# => 15

This works for all integer operations. For complex operations like XOR, CUDAAAAGH breaks them up into simpler additions and multiplications that will be more familiar to our computation partners. It then combines their answers behind the scenes to calculate the requested XOR:

from CUDAAAAGH import CUDAAAAGHInt

x = CUDAAAAGHInt(0b010100100)

y = x ^ CUDAAAAGHInt(0b111100101)

print(y)

# => 321

And before you ask - yes you can absolutely use CUDAAAAGH to train AI models. Stick around until the end for more details.

I know what you’re thinking: this is genius, it’s revolutionary, but Bitcoin mining is a game of speed. Is CUDAAAAGH fast enough? And to you I say: hell yes it’s almost fast enough, if you go by our 5-year projections and use our heterodox assumptions about the direction of the world economy.

Hold onto your cheque books everybody.

It’s time to mine

Today, calculating a hash takes the MinorMiner platform about 7 billion operations. An off-the-shelf ten-year-old can perform one addition every 10 seconds. Including a generous sleeping allowance, this means that they can compute 1 hash every 2,000 years. On the other hand, specialized mining rigs can compute 1 hash every 0.00000000001 seconds, and new blocks are mined every 10 minutes. These numbers don’t work for MinorMiner - yet.

Fortunately MinorMiner is in a fundamentally strong position in the value chain. We’re fuelled by exhaust work that was previously completely wasted, which means that we don’t need to be uber-efficient in order to be competitive. However, we do still need to complete each hash within the time it takes for a new block to be mined. Otherwise, even if we find a successful hash that would have mined us a block and won us some Bitcoin, someone else will have mined that block already.

This is why MinorMiner’s number one focus is on turbo-charing our hashrate. Let me tell about our top three strategies: parallelisation, curriculum optimisation, and teacher incentive alignment.

1. Parallelisation

First, parallelisation. Right now, a single partner works on a single hash. This means that even though adding more partners allows us to calculate more hashes at the same time, it doesn’t decrease the end-to-end time it takes to calculate a single hash.

However, we can distribute work between computation partners far more cunningly than we do today. We can split up the calculations required to compute a hash into independent chunks, and we can give the chunks to different computation partners to work on in parallel. Once all of the chunks are done, we can combine them and take a big leap forward in a single hash, instead of many small leaps in lots of different hashes. Spreading out work like this allows us to decrease the time it takes us to calculate a single hash. This will significantly increase our competitiveness.

“But Hobert, SHA-256 can’t be parallelised!” I hear you squawking. “It uses a sequential block structure, where the output of each block is the input to the next block! This means that you can’t calculate later blocks until you’ve first calculated earlier ones. This makes parallelisation impossible!”

You’re right, oddly-well-informed heckler! Most implementations of SHA-256 can’t be usefully parallelised. However, remember that CUDAAAAGH breaks bitwise operations like AND, OR, and XOR into a large number of additions and multiplications. Many of the sub-calculations inside a single XOR operation are in fact independent and don’t depend on each other. This makes them easy to parallelise and get the massive speedups I’ve been promising.

For example, here’s our current, naive implementation of XOR:

class CUDAAAAGHInt:

def __init__(self, val: int):

self.val = val

def __xor__(self, other: 'CUDAAAAGHInt') -> 'CUDAAAAGHInt':

result = CUDAAAAGHInt(0)

# Calculate the value of each bit, and use bit-shifting to combine

# them using standard integer arithemtic.

for i in range(max(self.bit_length(), other.bit_length())):

bit_self = self._ith_bit(CUDAAAAGHInt(i))

bit_other = other._ith_bit(CUDAAAAGHInt(i))

xor_bit = bit_self + bit_other - CUDAAAAGHInt(2) * bit_self * bit_other

result += xor_bit << CUDAAAAGHInt(i)

return result

def _ith_bit(self, i: 'CUDAAAAGHInt') -> 'CUDAAAAGHInt':

return CUDAAAAGHInt((self.val >> i.val) & 1)

def bit_length(self) -> int:

return self.val.bit_length()

This implementation is serial and slow - just look at that for-loop! But now look even closer. Notice how each pass through the loop is entirely independent of all others. This means that we can calculate the value of each bit separately, in parallel, then combine all the results once we’re done. We can even compute bit_x and bit_y in parallel inside each loop.

Combining these tricks gives us a parallel implementation that looks something like this:

import asyncio

class CUDAAAAGHInt:

def __init__(self, val: int):

self.val = val

async def __xor__(self, other: 'CUDAAAAGHInt') -> 'CUDAAAAGHInt':

# Calculate a single bit XOR at position i

async def compute_bit_xor(i: int) -> 'CUDAAAAGHInt':

bit_self_task = asyncio.create_task(self._ith_bit(CUDAAAAGHInt(i)))

bit_other_task = asyncio.create_task(other._ith_bit(CUDAAAAGHInt(i)))

bit_self = await bit_self_task

bit_other = await bit_other_task

xor_bit = bit_self + bit_other - CUDAAAAGHInt(2) * bit_self * bit_other

return xor_bit << CUDAAAAGHInt(i)

# Determine the number of bits to process

max_bits = max(self.bit_length(), other.bit_length())

# Calculate all bits concurrently

tasks = [compute_bit_xor(i) for i in range(max_bits)]

all_bits = await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

# Sum the results

result = CUDAAAAGHInt(0)

for bit in all_bits:

result = result + bit

return result

async def _ith_bit(self, i: 'CUDAAAAGHInt') -> 'CUDAAAAGHInt':

return CUDAAAAGHInt((self.val >> i.val) & 1)

def bit_length(self) -> int:

return self.val.bit_length()

This will reduce the time it takes for us to calculate the XOR of two numbers M and N by a factor of about log2(max(M, N)). We’re mostly dealing with 32-bit integers, so this is a 5x speedup.

I’m sure you’ve all noticed that we could use a map-reduce approach to turbocharge that last sum as well. I’m also sure that a couple of you have noticed that we could write a monad that allows us to elegantly parallelise everything, everywhere. I’m even more sure that one of you has already emailed me an implementation of this monad, written in a Lisp dialect that you designed yourself. Fair warning to that person - I am unlikely to read it.

2. Curriculum optimisation

A 5x speedup in our xor implementation is very, very, deeply impressive, but it’s still a hack. Decomposing XOR calculations into additions and multiplications is fundamentally inefficient, and it imposes a hard ceiling on our performance. In order to achieve true speed and elegance, we need to perform the XOR directly, without splitting it up.

The reason that we don’t do this already is because most children can’t calculate even a basic 8-bit XOR. I know! I was as shocked as you when I found out. But these kids aren’t stupid; their ignorance isn’t their fault. They’re being let down by a broken system that fails to teach them the skills they need to compete in today’s highly-specialised economy.

This is why we’ve successfully lobbied to have XOR calculations added to the first grade syllabus, starting in the coming autumn term. We’ve produced a textbook containing all the important bitwise operations that every 7 year-old should know, including XOR, AND, OR, and bitshifts. This will allow us to ask our computation partners truly useful questions like What is 2136782 ^ 2136821?, instead of spoonfeeding them piles of simpler calculations. We predict that this will lead to a further hashrate speedup of approximately 100x, and we expect to start seeing results in Q1 next year, after the end-of-unit quizzes start to bite.

“Teach a man to hash and you’ll etc etc.”

But why stop with XORs? Think about how legacy mining has evolved over the last decade or so. The first Bitcoins were mined on normal computers, with normal CPUs. Nowadays all bitcoins are mined using specialised computers called ASICs, hardwired to calculates hashes and nothing out. In order to compete, we have to train human ASICs.

Kids need to learn how to calculate a SHA-256 themselves, end-to-end. This is why we’re such vocal supporters of SB-1337 - “No Child Left Unmined.” SB-1337 will replace the outdated year 7 maths syllabus with an in-depth, end-to-end course on calculating SHA-256 hashes by hand. It will allow us to stop sending students trivial additions and multiplications, and send them real maths instead:

Question 1:

What is the SHA-256 hash of 01003ba3edfd7a...? (3 marks)

Question 2:

What is the SHA-256 hash of 01003ba3edfd7b...? (3 marks)

We’ll be able to turn their homework directly into bitcoins, with no intermediate calculations required. At this point all we’ll need to do is scale. Which brings me to our final speedup technique: Teacher Incentive Alignment

3. Teacher Incentive Alignment

At first some of our new Distribution Associates (or teachers, as they’re known as in the legacy system) were…hesitant to embrace our new, hash-centric curriculum. Fortunately this changed when they learned about our Teacher Incentive Alignment program (TIA).

TIA allows us to compensate Distribution Associates for their hard work, using a sliding-scale fee for every billion hashes produced by their Computation Partners (or, “students”). With TIA, whenever we profit, they profit. The Computation Partners profit too of course, through the invaluable knowledge and practice that they get by participating in MinorMiner.

We’ve found that Distribution Associates who are in the TIA program set 1,000,000% more homework questions than those who are not. For example, one particularly keen associate set their partners the following quiz:

Question 1 of 1,471,126,723

What is the SHA-256 hash of 01003ba3edfd7a...? (0.0000000001 marks)

Question 2 of 1,471,126,723

What is the SHA-256 hash of 01003ba3edfd7b...? (0.0000000001 marks)

(and so on for 1,471,126,721 more questions)

Some Associates were initially concerned that their Computation Partners might balk at such ambitious workloads, despite all the knowledge and hands-on-experience and so on that it would give them. They worried that some Partners might cheat and use specialized mining software to do their hashing homework for them. Fortunately we were able to use spreadsheets and a lot of winking to help most of them realise that this might not actually be a problem.

MinorMiner would like to make it clear that we do not in any way condone cheating. Use of our Homework Submission APIs and their associated SDKs is strictly prohibited.

So in short - yes, we are going to be fast enough. Through parallelisation, curriculum optimisation, and teacher incentive alignment, we believe that we are extremely well-positioned to speed up and scale massively in the coming years. Then what?

From Bitcoin to AI

After we’ve perfected the bitcoin use-case, we’ll pivot straight to AI. We’re already extending CUDAAAAGH with pytorch bindings that will allow users to run their training and inference code using our unique computing platform. Most children don’t know much matrix algebra, but matrix algebra is just addition and multiplication wrapped up in funny symbols. All we need to do is implement matrix multiplication using CUDAAAAGH and we’ll be very, very golden. And if our next legislative priority (SB-80085) passes, matrix algebra will soon be on the year eight curriculum too. It’s curriculum optimisation all over again.

def matmul(m1: CUDAAAAGHMatrix, m2: CUDAAAAGHMatrix) -> CUDAAAAGHMatrix:

# (Implementation left as an exercise for the reader, you get

# the joke by now)

Applying CUDAAAAGH to AI raises some delightful philosophical questions. Were you already deeply confused about whether sufficiently advanced AI models should count as conscious beings? Are we going to be morally obliged to care about their welfare? How much more confusing do these questions become if the AI models are an emergent property of billions of children doing their maths homework?

And what will we do after AI? Cloud computing, ladies and gentlemen, cloud computing. Children are commodity hardware. Our big, audacious goal is to implement an entire computer using them. Everywhere that a computer normally has an electron, we’ll replace it with a school-aged child doing their maths homework. CPUs become specialised children performing incredibly-specialised operations. Hard-drives become arrays of children remembering 1s and 0s. Motherboards become lines of children deciding what messages to send to the others. Think about the implications! Free computers for everyone!

That’s all I have to say today, thank you for listening. Believe in children! Invest in the MinorMiner pre-seed! Form an orderly line! Make your cheques payable to “Hobert Reaton.” No madam, there’s no “LLC” at the end. Just “Hobert Reaton.” I also accept cash and a wide range of memecoins. Here’s my wallet address. Thank you.

CUDAAAAGH is available on GitHub. It can also be installed from PyPi using pip install CUDAAAAGH although I can’t imagine why on earth you would do this.

Hello! Hello! Welcome, welcome. My name is Hobert Reaton, and I’m here in this shabby motel conference room to present you with yet another once-in-a-lifetime investment opportunity.

Look at this picture. Tell me what you see:

Do you see learning? Self-improvement? The future leaders of our country?

I’ll tell you what I see: wasted computing power.

Between the ages of 5 and 18, the average child in full-time education completes about 5 maths worksheets a week. Each worksheet has 20 questions. This means that over the course of their school career, every single one of our kids performs about 80,000 calculations.

At the moment we completely waste their work. A student figures out that 5+5=10 and 7x7=49. This motivates them; they’re energised by their success. But then what do we do with the fruits of their labour? Nothing! We throw the fruit away, to rot in the void. “We knew that already,” we tell our children. “Your ideas don’t matter.” Unlike the rest of society, I believe that kids deserve to feel appreciated. I believe that their achievements are valuable.

That’s why I founded MinorMiner.

What is MinorMiner?

MinorMiner is a platform that allows school-age children to monetise their maths homework by using it to mine Bitcoin. Yes, you heard me. We send children their homework, they crunch through it, and then together we transform their sweat into digital gold. This isn’t some rinky-dink incentive program where we bribe children to care about multiplication. Homework is the essential raw material that feeds our machine. We need these kids. No kids; no Bitcoin.

In order to understand the innovation that makes MinorMiner possible, we first need to understand how Bitcoin is mined today. Right now, people mine Bitcoin by using computers to solve complex mathematical puzzles. The puzzles look like this:

- Take the list of the Bitcoin transactions that have occurred since the last Bitcoin was mined. Check that they’re all correctly authorized and that none of them spend money that the creator doesn’t have.

- Choose a string of extra letters and numbers to add on to the end of this list (a nonce). This is your attempt to solve the puzzle.

- Pass the list and your extra characters through an extremely complex function called the SHA-256 hash function (technically you pass it through the function twice). The hash function chops and slices and spins and dices the input around, seemingly (but not actually) at random. At the end it spits out a number

- The puzzle that you’re trying to solve is: what combination of letters and numbers from step 2 cause the output from step 3 to be less than some small target number?

There’s no elegant way to solve these puzzles. The only thing for Bitcoin miners to do is to guess inputs to step 2, over and over and over again, until they find one that happens to satisfy the criteria in step 4. When a miner guesses a right answer we say that they’ve “mined” a new “block”. They attach their solution to the blockchain to show that they’ve verified the transactions in the block, and they’re rewarded with new bitcoin. Their work, along with a couple of extra steps that I’ve hand-waved over, ensures that the blockchain stays safe and secure.

However, it also requires an incredible amount of electricity - around 150TWh per year, or 1% of the world’s total energy consumption. What if there was a better, more efficient way to achieve the same thing?

This is where MinorMiner and school-aged children come in. “But Bitcoin mining sounds hard!” I hear you wail. “My child has only a rudimentary grasp of basic algorithms!” True, true - but the magic is that the children on our platform don’t need to know how to mine Bitcoin, and they won’t even know that they’re doing it. Our team has converted the SHA-256 hashing algorithm used by the bitcoin blockchain into a sequence of elementary arithmetic questions that even the dullest dullard can answer. Solving a blockchain puzzle used to require understanding and executing a SHA-256 hash. Now all it takes is skipping through a few trillion simple brainteasers.

5+3=?10*5=?Is 102 bigger than 67? (y/n)- And so on

The kids do these sums - we take care of the rest.

How does the MinorMiner platform work?

The heart of MinorMiner is a centralised system that manages our mining. The system decomposes a SHA-256 hash computation into simple arithmetic questions, and works out which of these questions need answering next. Simple enough - but how do we get the questions to the kids? Three words: online maths quizzes.

You see, MinorMiner also has a maths learning platform that we sell to schools all over the world. Our platform isn’t particularly good, but we give department heads a generous revenue share and so this tends not to matter. Once a teacher (or “distribution associate” as we like to call them) is set up on MinorMiner, they assign a quiz to their class as homework. In the evening their children (or “computation partners”) log into the MinorMiner portal and answer their quiz for the day, which consists of whatever questions our hashing system needs doing next. By way of compensation their distribution associate doesn’t give them a detention. We collect their answers and use them to continue calculating a hash. When one partner finishes their quiz, the next partner continues calculating from where they left off.

We have to be careful - a hash is a delicate thing. One tiny mistake in one tiny step and - poof! - the whole calculation is completely, irreversibly screwed. That’s why send each calculation to two separate computation partners. If their answers disagree then we escalate to a slightly older partner to adjudicate. We maintain a rating for each partner based on their accuracy. If their rating drops below 4.3 stars then they are invited to undergo additional training to help them get back to the standard expected for MinorMiner partners. If such improvement is not forthcoming then they are invited to seek maths education elsewhere.

Any questions so far? No? Then it’s time for me to show you our real technological breakthrough.

CUDAAAAGH

We write our mining code using a Python library called Centralized Underage Distributed Arithmetic - Automated Assignment And Group Hashing (CUDAAAAGH). CUDAAAAGH allows us to distribute any complex computation across an infinitely-scalable pool of computation partners. We’ve open-sourced it on GitHub and PyPi.

To use it, we run pip install CUDAAAAGH and then use its CUDAAAAGHInt class everywhere we would normally use Python’s standard integer type. Aside from that, we write all of our code as normal. When we execute our program, CUDAAAAGH automatically offloads any arithmetic computations to our network of computation partners, instead of burdening our own CPUs.

For example:

from CUDAAAAGH import CUDAAAAGHInt

x = CUDAAAAGHInt(5)

y = x + CUDAAAAGHInt(10)

# Behind the scenes, this sends the calculation "5+10" to a computation

# partner. Execution pauses until we receive an answer.

print(f"The answer is: {y}")

# => 15

This works for all integer operations. For complex operations like XOR, CUDAAAAGH breaks them up into simpler additions and multiplications that will be more familiar to our computation partners. It then combines their answers behind the scenes to calculate the requested XOR:

from CUDAAAAGH import CUDAAAAGHInt

x = CUDAAAAGHInt(0b010100100)

y = x ^ CUDAAAAGHInt(0b111100101)

print(y)

# => 321

And before you ask - yes you can absolutely use CUDAAAAGH to train AI models. Stick around until the end for more details.

I know what you’re thinking: this is genius, it’s revolutionary, but Bitcoin mining is a game of speed. Is CUDAAAAGH fast enough? And to you I say: hell yes it’s almost fast enough, if you go by our 5-year projections and use our heterodox assumptions about the direction of the world economy.

Hold onto your cheque books everybody.

It’s time to mine

Today, calculating a hash takes the MinorMiner platform about 7 billion operations. An off-the-shelf ten-year-old can perform one addition every 10 seconds. Including a generous sleeping allowance, this means that they can compute 1 hash every 2,000 years. On the other hand, specialized mining rigs can compute 1 hash every 0.00000000001 seconds, and new blocks are mined every 10 minutes. These numbers don’t work for MinorMiner - yet.

Fortunately MinorMiner is in a fundamentally strong position in the value chain. We’re fuelled by exhaust work that was previously completely wasted, which means that we don’t need to be uber-efficient in order to be competitive. However, we do still need to complete each hash within the time it takes for a new block to be mined. Otherwise, even if we find a successful hash that would have mined us a block and won us some Bitcoin, someone else will have mined that block already.

This is why MinorMiner’s number one focus is on turbo-charing our hashrate. Let me tell about our top three strategies: parallelisation, curriculum optimisation, and teacher incentive alignment.

1. Parallelisation

First, parallelisation. Right now, a single partner works on a single hash. This means that even though adding more partners allows us to calculate more hashes at the same time, it doesn’t decrease the end-to-end time it takes to calculate a single hash.

However, we can distribute work between computation partners far more cunningly than we do today. We can split up the calculations required to compute a hash into independent chunks, and we can give the chunks to different computation partners to work on in parallel. Once all of the chunks are done, we can combine them and take a big leap forward in a single hash, instead of many small leaps in lots of different hashes. Spreading out work like this allows us to decrease the time it takes us to calculate a single hash. This will significantly increase our competitiveness.

“But Hobert, SHA-256 can’t be parallelised!” I hear you squawking. “It uses a sequential block structure, where the output of each block is the input to the next block! This means that you can’t calculate later blocks until you’ve first calculated earlier ones. This makes parallelisation impossible!”

You’re right, oddly-well-informed heckler! Most implementations of SHA-256 can’t be usefully parallelised. However, remember that CUDAAAAGH breaks bitwise operations like AND, OR, and XOR into a large number of additions and multiplications. Many of the sub-calculations inside a single XOR operation are in fact independent and don’t depend on each other. This makes them easy to parallelise and get the massive speedups I’ve been promising.

For example, here’s our current, naive implementation of XOR:

class CUDAAAAGHInt:

def __init__(self, val: int):

self.val = val

def __xor__(self, other: 'CUDAAAAGHInt') -> 'CUDAAAAGHInt':

result = CUDAAAAGHInt(0)

# Calculate the value of each bit, and use bit-shifting to combine

# them using standard integer arithemtic.

for i in range(max(self.bit_length(), other.bit_length())):

bit_self = self._ith_bit(CUDAAAAGHInt(i))

bit_other = other._ith_bit(CUDAAAAGHInt(i))

xor_bit = bit_self + bit_other - CUDAAAAGHInt(2) * bit_self * bit_other

result += xor_bit << CUDAAAAGHInt(i)

return result

def _ith_bit(self, i: 'CUDAAAAGHInt') -> 'CUDAAAAGHInt':

return CUDAAAAGHInt((self.val >> i.val) & 1)

def bit_length(self) -> int:

return self.val.bit_length()

This implementation is serial and slow - just look at that for-loop! But now look even closer. Notice how each pass through the loop is entirely independent of all others. This means that we can calculate the value of each bit separately, in parallel, then combine all the results once we’re done. We can even compute bit_x and bit_y in parallel inside each loop.

Combining these tricks gives us a parallel implementation that looks something like this:

import asyncio

class CUDAAAAGHInt:

def __init__(self, val: int):

self.val = val

async def __xor__(self, other: 'CUDAAAAGHInt') -> 'CUDAAAAGHInt':

# Calculate a single bit XOR at position i

async def compute_bit_xor(i: int) -> 'CUDAAAAGHInt':

bit_self_task = asyncio.create_task(self._ith_bit(CUDAAAAGHInt(i)))

bit_other_task = asyncio.create_task(other._ith_bit(CUDAAAAGHInt(i)))

bit_self = await bit_self_task

bit_other = await bit_other_task

xor_bit = bit_self + bit_other - CUDAAAAGHInt(2) * bit_self * bit_other

return xor_bit << CUDAAAAGHInt(i)

# Determine the number of bits to process

max_bits = max(self.bit_length(), other.bit_length())

# Calculate all bits concurrently

tasks = [compute_bit_xor(i) for i in range(max_bits)]

all_bits = await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

# Sum the results

result = CUDAAAAGHInt(0)

for bit in all_bits:

result = result + bit

return result

async def _ith_bit(self, i: 'CUDAAAAGHInt') -> 'CUDAAAAGHInt':

return CUDAAAAGHInt((self.val >> i.val) & 1)

def bit_length(self) -> int:

return self.val.bit_length()

This will reduce the time it takes for us to calculate the XOR of two numbers M and N by a factor of about log2(max(M, N)). We’re mostly dealing with 32-bit integers, so this is a 5x speedup.

I’m sure you’ve all noticed that we could use a map-reduce approach to turbocharge that last sum as well. I’m also sure that a couple of you have noticed that we could write a monad that allows us to elegantly parallelise everything, everywhere. I’m even more sure that one of you has already emailed me an implementation of this monad, written in a Lisp dialect that you designed yourself. Fair warning to that person - I am unlikely to read it.

2. Curriculum optimisation

A 5x speedup in our xor implementation is very, very, deeply impressive, but it’s still a hack. Decomposing XOR calculations into additions and multiplications is fundamentally inefficient, and it imposes a hard ceiling on our performance. In order to achieve true speed and elegance, we need to perform the XOR directly, without splitting it up.

The reason that we don’t do this already is because most children can’t calculate even a basic 8-bit XOR. I know! I was as shocked as you when I found out. But these kids aren’t stupid; their ignorance isn’t their fault. They’re being let down by a broken system that fails to teach them the skills they need to compete in today’s highly-specialised economy.

This is why we’ve successfully lobbied to have XOR calculations added to the first grade syllabus, starting in the coming autumn term. We’ve produced a textbook containing all the important bitwise operations that every 7 year-old should know, including XOR, AND, OR, and bitshifts. This will allow us to ask our computation partners truly useful questions like What is 2136782 ^ 2136821?, instead of spoonfeeding them piles of simpler calculations. We predict that this will lead to a further hashrate speedup of approximately 100x, and we expect to start seeing results in Q1 next year, after the end-of-unit quizzes start to bite.

“Teach a man to hash and you’ll etc etc.”

But why stop with XORs? Think about how legacy mining has evolved over the last decade or so. The first Bitcoins were mined on normal computers, with normal CPUs. Nowadays all bitcoins are mined using specialised computers called ASICs, hardwired to calculates hashes and nothing out. In order to compete, we have to train human ASICs.

Kids need to learn how to calculate a SHA-256 themselves, end-to-end. This is why we’re such vocal supporters of SB-1337 - “No Child Left Unmined.” SB-1337 will replace the outdated year 7 maths syllabus with an in-depth, end-to-end course on calculating SHA-256 hashes by hand. It will allow us to stop sending students trivial additions and multiplications, and send them real maths instead:

Question 1:

What is the SHA-256 hash of 01003ba3edfd7a...? (3 marks)

Question 2:

What is the SHA-256 hash of 01003ba3edfd7b...? (3 marks)

We’ll be able to turn their homework directly into bitcoins, with no intermediate calculations required. At this point all we’ll need to do is scale. Which brings me to our final speedup technique: Teacher Incentive Alignment

3. Teacher Incentive Alignment

At first some of our new Distribution Associates (or teachers, as they’re known as in the legacy system) were…hesitant to embrace our new, hash-centric curriculum. Fortunately this changed when they learned about our Teacher Incentive Alignment program (TIA).

TIA allows us to compensate Distribution Associates for their hard work, using a sliding-scale fee for every billion hashes produced by their Computation Partners (or, “students”). With TIA, whenever we profit, they profit. The Computation Partners profit too of course, through the invaluable knowledge and practice that they get by participating in MinorMiner.

We’ve found that Distribution Associates who are in the TIA program set 1,000,000% more homework questions than those who are not. For example, one particularly keen associate set their partners the following quiz:

Question 1 of 1,471,126,723

What is the SHA-256 hash of 01003ba3edfd7a...? (0.0000000001 marks)

Question 2 of 1,471,126,723

What is the SHA-256 hash of 01003ba3edfd7b...? (0.0000000001 marks)

(and so on for 1,471,126,721 more questions)

Some Associates were initially concerned that their Computation Partners might balk at such ambitious workloads, despite all the knowledge and hands-on-experience and so on that it would give them. They worried that some Partners might cheat and use specialized mining software to do their hashing homework for them. Fortunately we were able to use spreadsheets and a lot of winking to help most of them realise that this might not actually be a problem.

MinorMiner would like to make it clear that we do not in any way condone cheating. Use of our Homework Submission APIs and their associated SDKs is strictly prohibited.

So in short - yes, we are going to be fast enough. Through parallelisation, curriculum optimisation, and teacher incentive alignment, we believe that we are extremely well-positioned to speed up and scale massively in the coming years. Then what?

From Bitcoin to AI

After we’ve perfected the bitcoin use-case, we’ll pivot straight to AI. We’re already extending CUDAAAAGH with pytorch bindings that will allow users to run their training and inference code using our unique computing platform. Most children don’t know much matrix algebra, but matrix algebra is just addition and multiplication wrapped up in funny symbols. All we need to do is implement matrix multiplication using CUDAAAAGH and we’ll be very, very golden. And if our next legislative priority (SB-80085) passes, matrix algebra will soon be on the year eight curriculum too. It’s curriculum optimisation all over again.

def matmul(m1: CUDAAAAGHMatrix, m2: CUDAAAAGHMatrix) -> CUDAAAAGHMatrix:

# (Implementation left as an exercise for the reader, you get

# the joke by now)

Applying CUDAAAAGH to AI raises some delightful philosophical questions. Were you already deeply confused about whether sufficiently advanced AI models should count as conscious beings? Are we going to be morally obliged to care about their welfare? How much more confusing do these questions become if the AI models are an emergent property of billions of children doing their maths homework?

And what will we do after AI? Cloud computing, ladies and gentlemen, cloud computing. Children are commodity hardware. Our big, audacious goal is to implement an entire computer using them. Everywhere that a computer normally has an electron, we’ll replace it with a school-aged child doing their maths homework. CPUs become specialised children performing incredibly-specialised operations. Hard-drives become arrays of children remembering 1s and 0s. Motherboards become lines of children deciding what messages to send to the others. Think about the implications! Free computers for everyone!

That’s all I have to say today, thank you for listening. Believe in children! Invest in the MinorMiner pre-seed! Form an orderly line! Make your cheques payable to “Hobert Reaton.” No madam, there’s no “LLC” at the end. Just “Hobert Reaton.” I also accept cash and a wide range of memecoins. Here’s my wallet address. Thank you.

CUDAAAAGH is available on GitHub. It can also be installed from PyPi using pip install CUDAAAAGH although I can’t imagine why on earth you would do this.