PyMyFlySpy: track your flight using its headrest data

04 Dec 2024

“Where are we daddy?” asked my five-year-old.

“We’ll land in about an hour,” I said.

“No I mean where are we? Are we flying over Italy yet?”

I wasn’t sure. Our flight was short and cheap and the seats didn’t have TV screens in the headrests. I looked around. I noticed a sticker encouraging me to connect to the in-flight wi-fi. That would do it, I thought. A site like FlightRadar would answer my little man’s question, down to the nearest few meters.

But unfortunately for him I’m the creator of PySkyWiFi (“completely free, unbelievably stupid wi-fi on long-haul flights”). Not paying for airplane internet is kind of my signature move. We’d need a different, offline strategy.

I had a think. When you connect to an airplane wi-fi network, you’re usually met with a payment page where you can purchase access to the internet. The page also usually gives you the same flight information that you’d find in the back of your headrest, like speed, direction, and estimated flight length. Perhaps it would have a map as well, I thought.

I pulled out my laptop, connected to the network, and loaded up the payment page. It did indeed show our wind speed, direction, and estimated time of arrival. But no map.

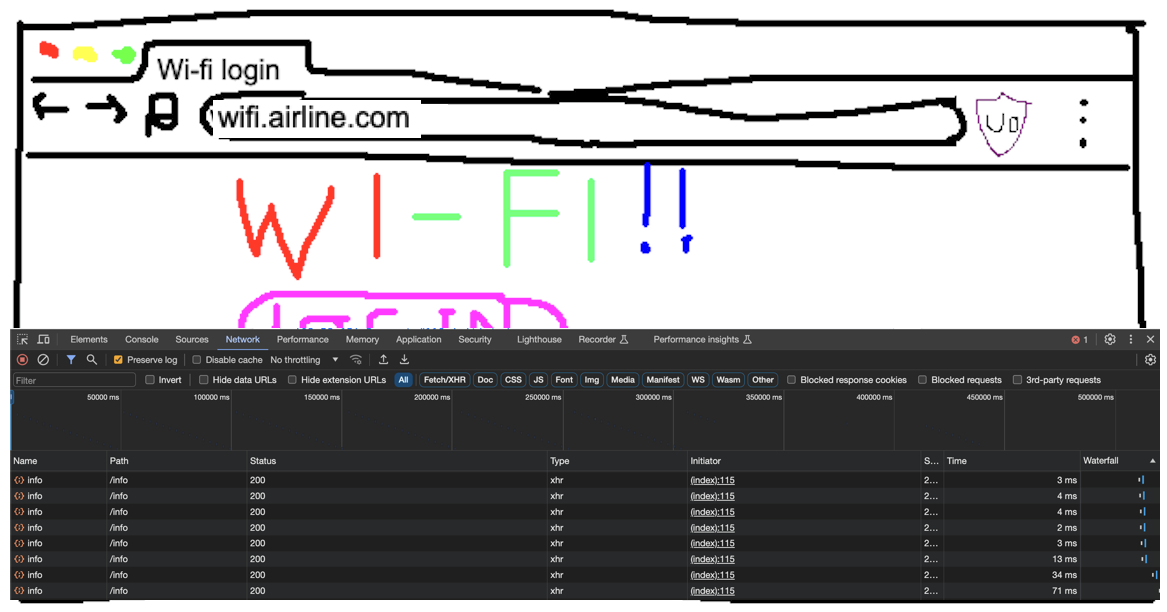

(It didn’t occur to me to screenshot the page so here’s an artist’s impression)

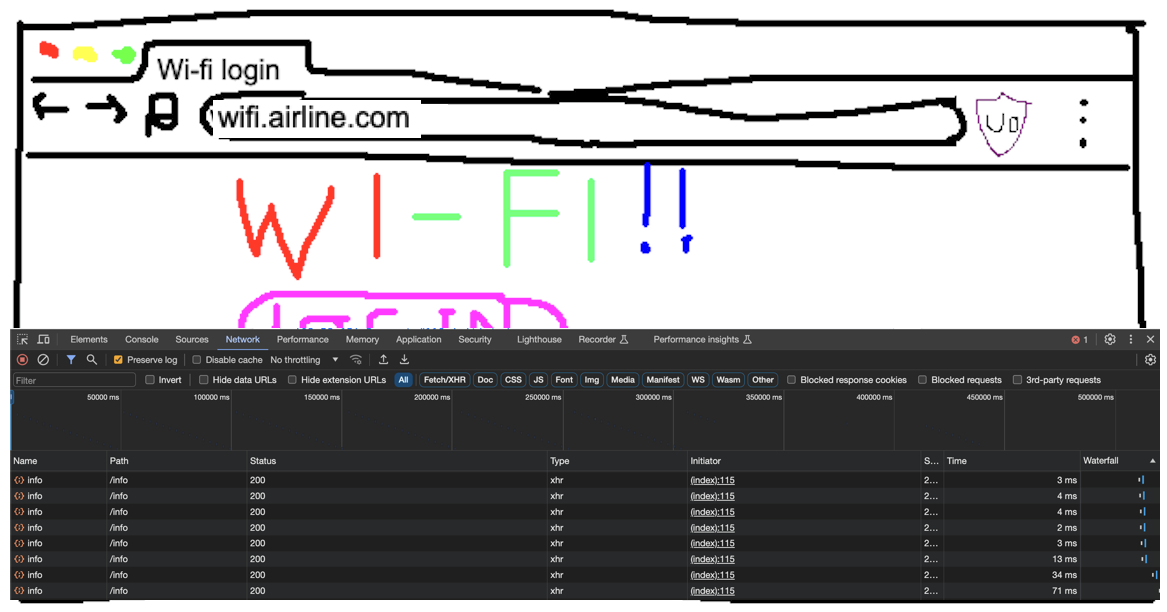

“Maybe the server that’s sending us this data is actually also sending us our location, but the web page isn’t displaying it,” I thought. I opened up the Chrome developer tools. I saw that my browser was making regular requests to a /info endpoint.

I clicked on one of the requests. This /info endpoint was indeed sending us a huge pile of data, including fields for ground_speed, wind_speed, and estimated_arrival_time. At the bottom of the response I noticed fields for latitude and longitude. My heart leapt. But then I looked closer. They were both null. Aerofoiled.

This looked like the end of the line. I was about to give up and tell my son that we were somewhere just north of Italy, probably…Europe somewhere. But then I was hit by two fantastic ideas.

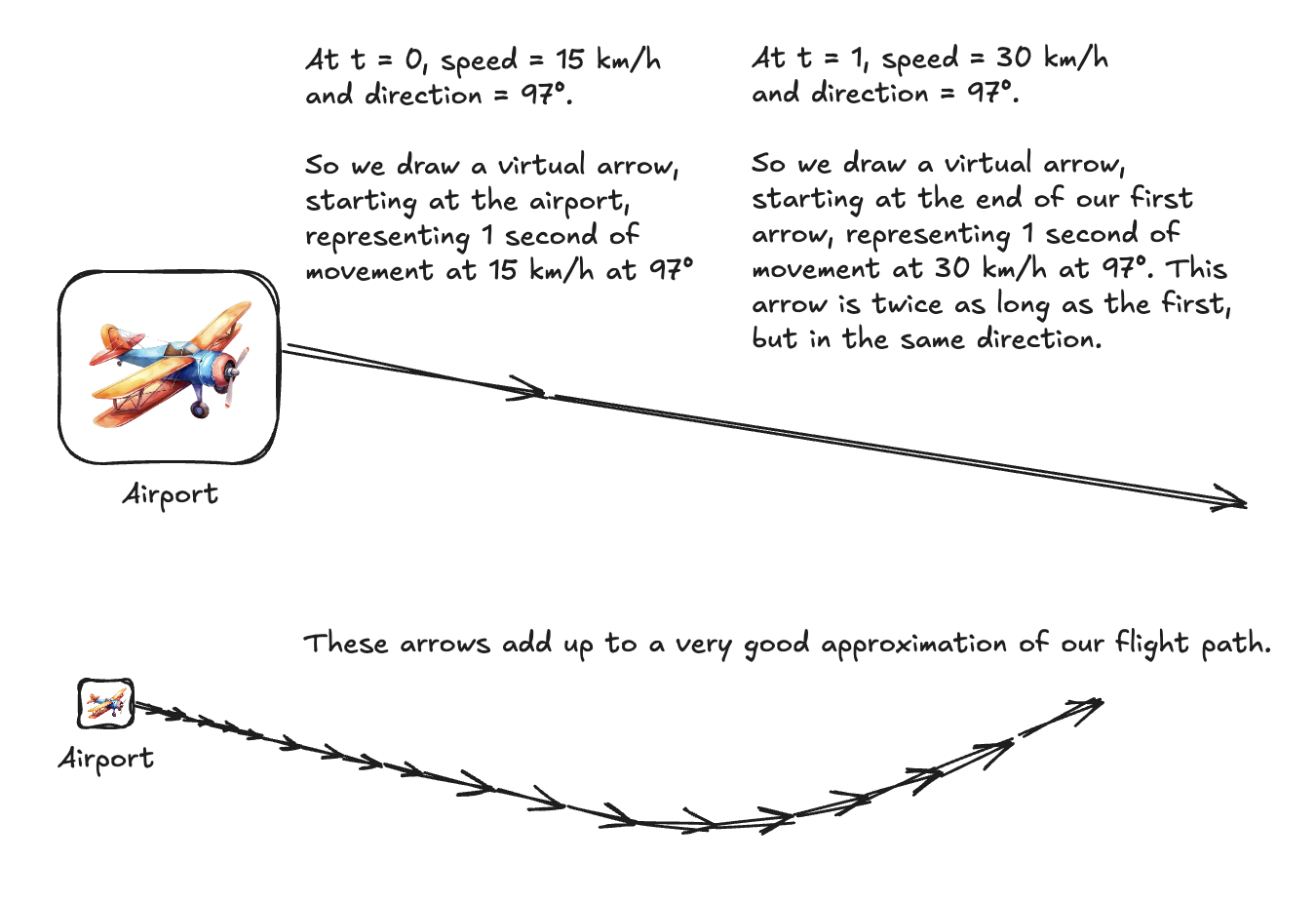

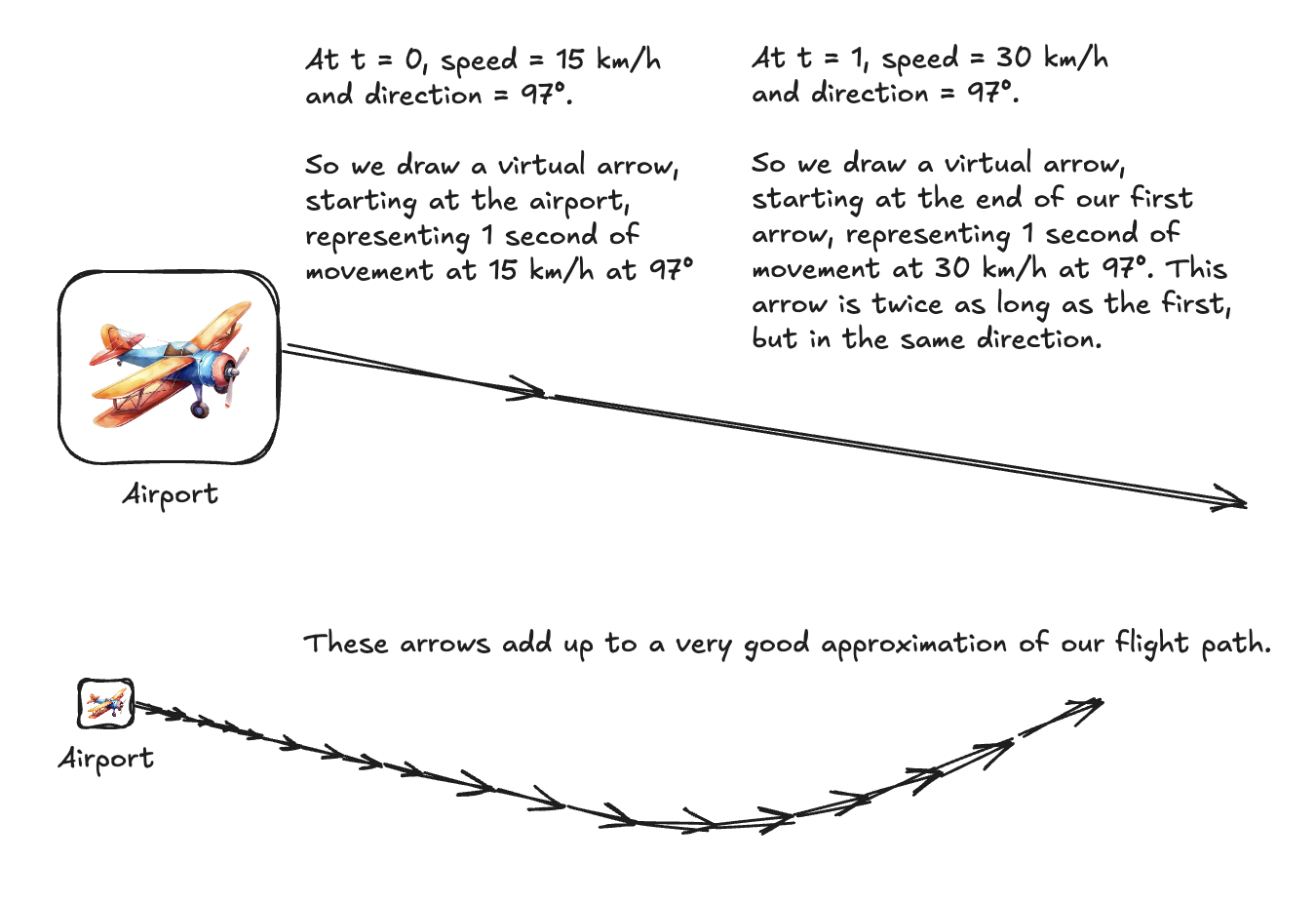

Fantastic idea number 1: the /info endpoint didn’t tell us our location, but it did tell us our precise, regularly-updated speed and direction. On our flight home I could track and save our speed and direction every second or so for the whole flight. I could use this information to estimate how far we had traveled in each second, and in which direction. I could dynamically calculate our position by starting at our airport’s co-ordinates, then adding on each second’s step.

Fantastic idea number 2: even if I had been able to find our latitude and longitude in the /info response, it wouldn’t have meant much to either me or my son. However, I could build a web app that ran on my laptop and showed us our dynamically calculated position on a map, in real time. The app could have automatically updating graphs of our ETA, wind direction, speed, altitude, and so on. Ooh and an interface for running arbitrary queries against the data. And event callbacks to allow me to programmatically trigger code based on flight info (“when our ETA is 2 hours exactly, block my access to netflix.com and open the latest draft of my unfinished novel”). My son would know where he was. I’d be a Good Dad.

I decided to call the app PyMyFlySpy in order to give it some brand association with PySkyWiFi, my airplane-related project. I couldn’t wait to get started. Unfortunately right now I was wedged in between a five-year-old and a two-year-old and we were all terrible at JavaScript. I waited, impatiently.

PyMyFlySpy

Eventually we landed. I built PyMyFlySpy during our holiday, over late evenings and one or two derelict afternoons while the rest of my family did normal-person fun things. I couldn’t figure out whether it was bad manners to use your laptop in artisanal Italian coffee shops, or which of them had wi-fi, so to my eternal shame I googled “starbucks near me” and planted myself in a corner with a skinny mochachino and typed away.

I finished PyMyFlySpy the day before we left. The code is available on GitHub and it’s easy to setup and run. It even has a “dummy” mode that allows you to demo it without being inside a plane, using a made-up flight.

Here’s what PyMyFlySpy can do:

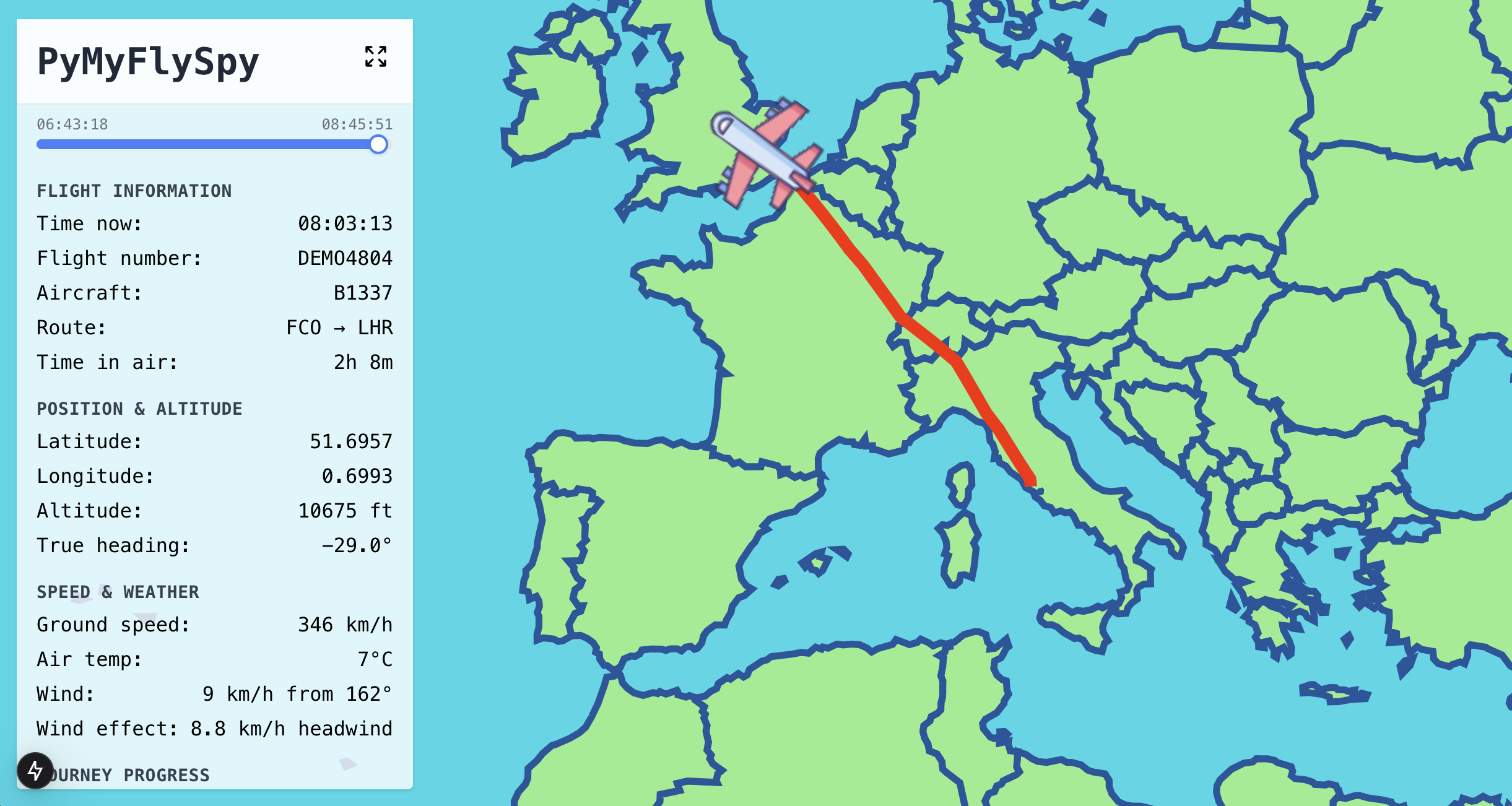

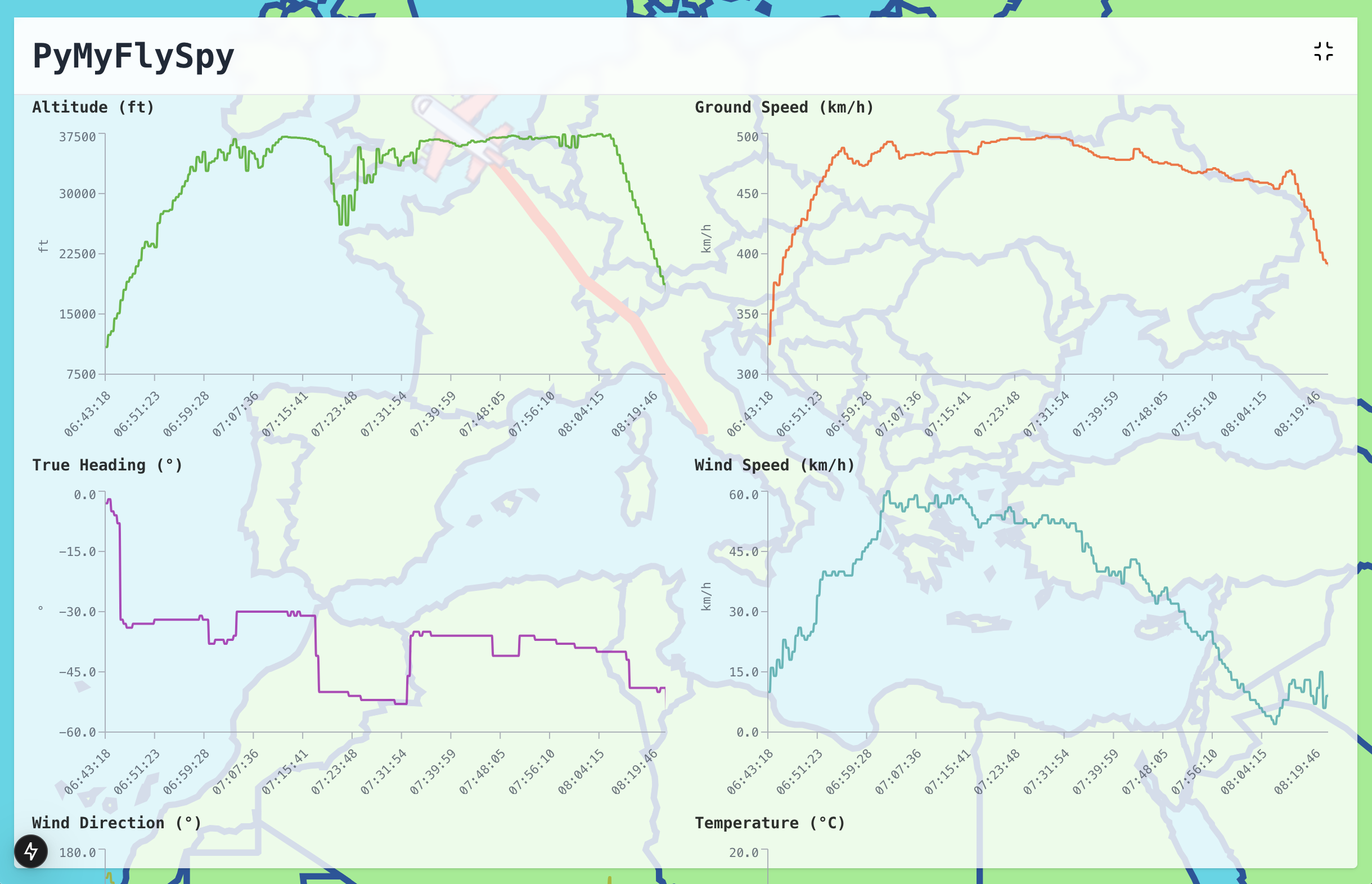

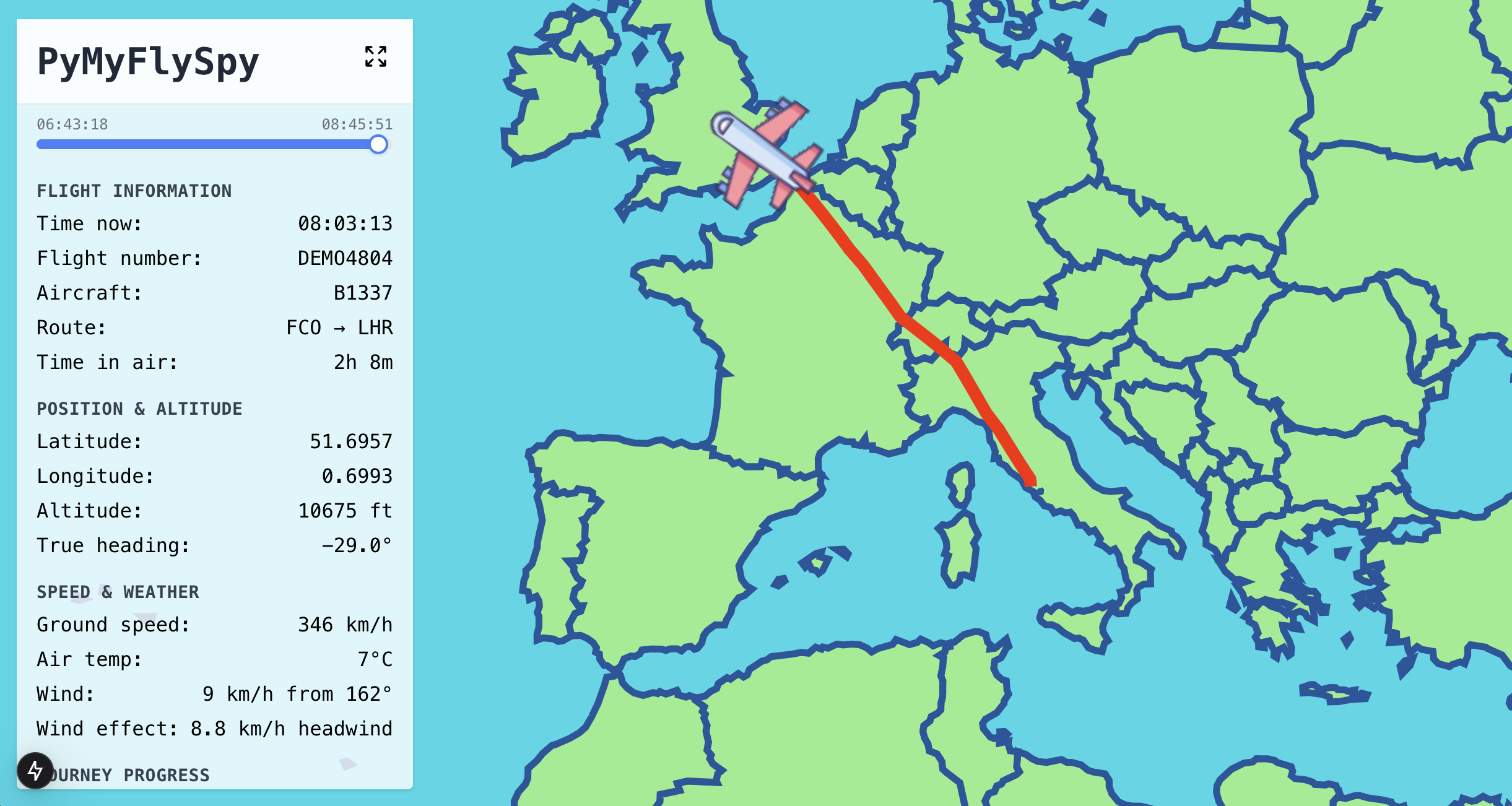

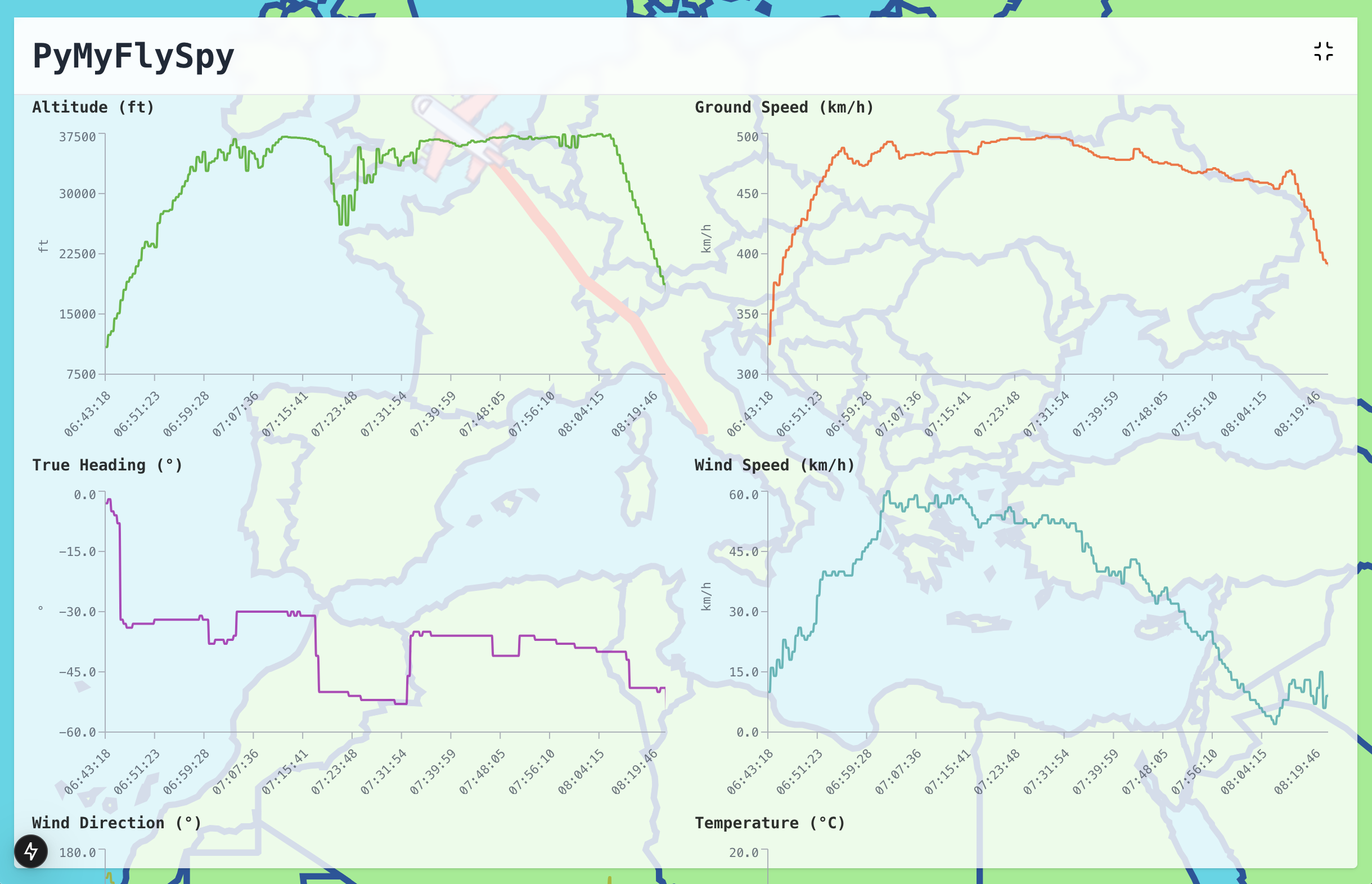

Maps and graphs

PyMySkySpy shows a map of your flightpath so far. It also shows your current flight metrics and how these metrics have changed over the course of your flight. It does this for all data available from the in-flight wi-fi, even data that isn’t usually displayed on the website or headrest screen. You can see exactly where you are and feel a bit like a pilot.

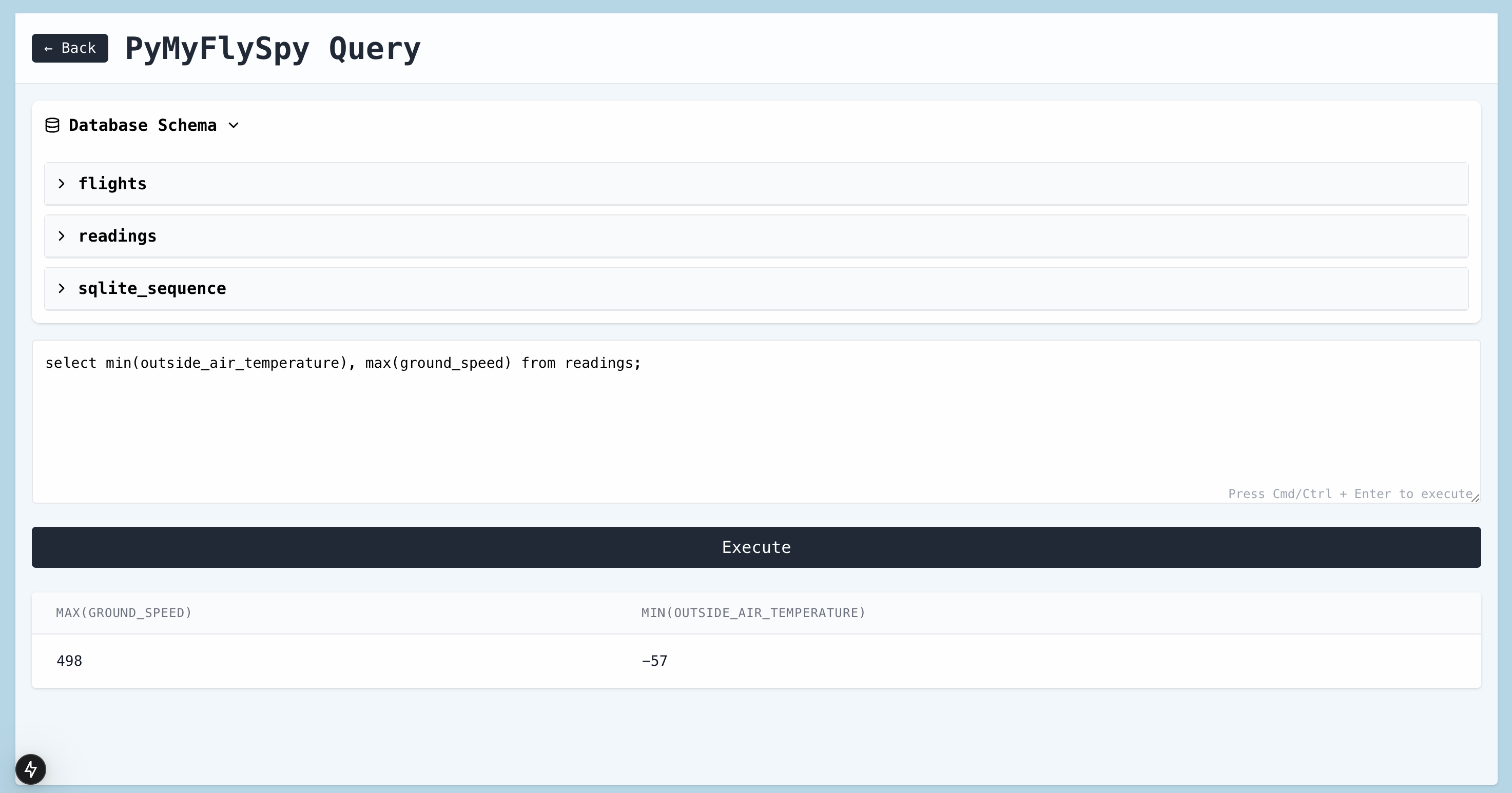

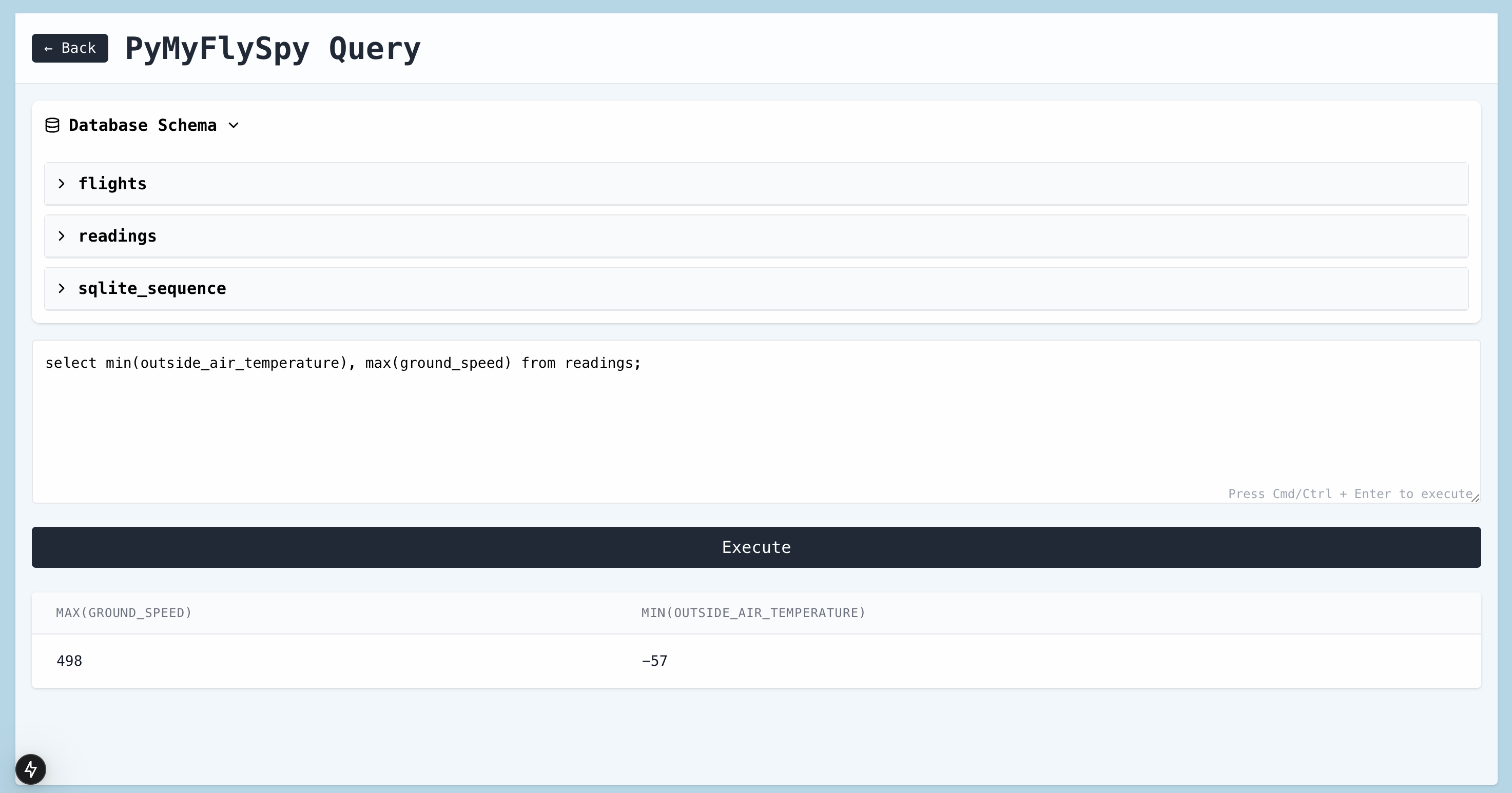

Query interface

PyMySkySpy saves all the data that it records to a database. Its UI has a page that allows you to write queries against the data to answer questions like “what’s our maximum speed so far, and when did we hit it?” or “how fast was the wind during that turbulence we just went through?”

I’m not claiming that this is hugely useful, but I do think it’s cool.

Multi-airline support

Different airlines have different wi-fi systems. A recorder for a JetBlue flight won’t work on AirFrance. Fortunately, PyMySkySpy allows you to easily add and use recorders for different airlines. You just have to load up their wi-fi landing page, open your browser’s developer tools, and figure out how to parse their page’s data like I did above. Then you add your new code to the PyMySkySpy config, and tell the recorder to use it. Everything else continues to work just the same.

System design

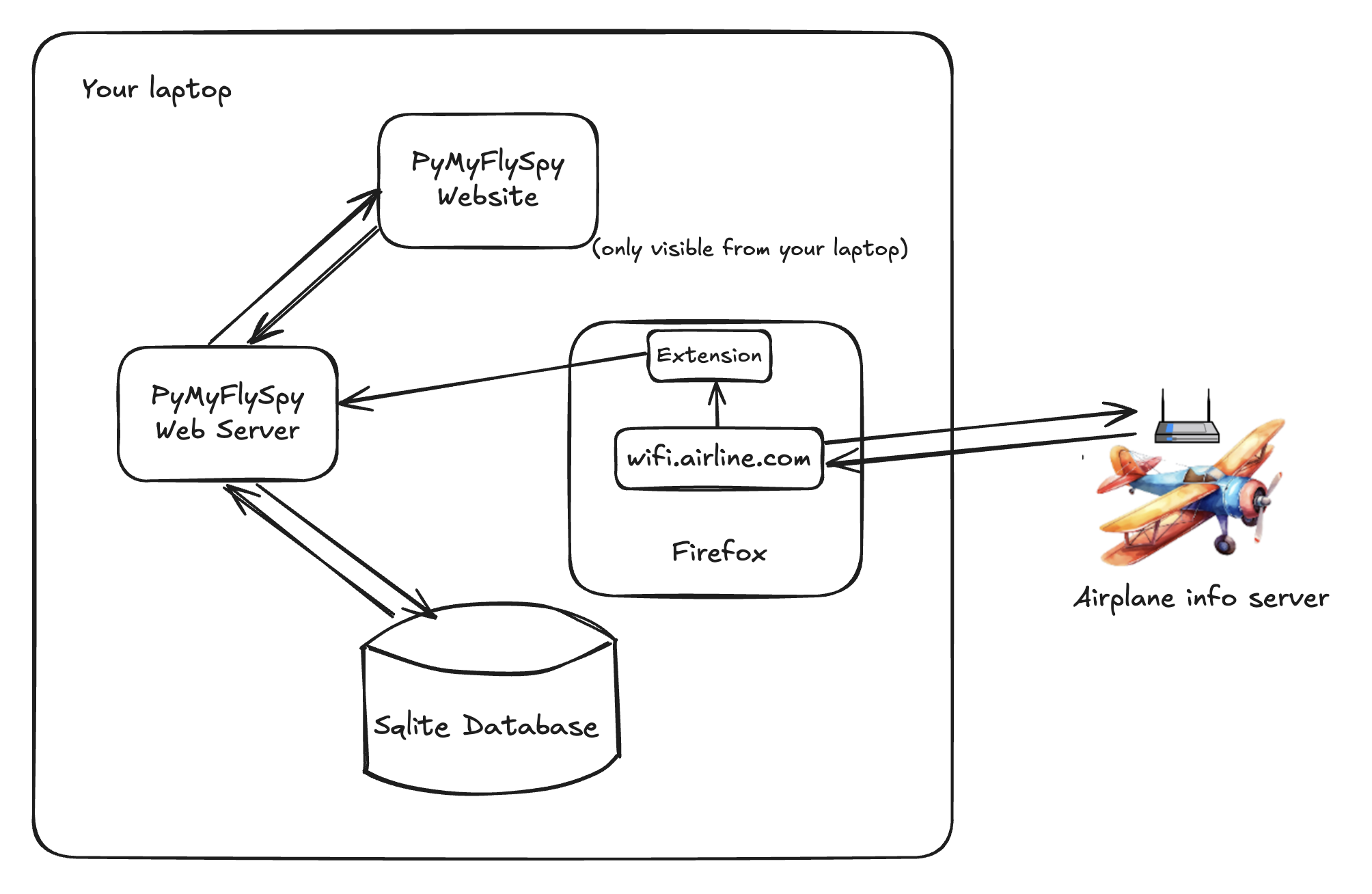

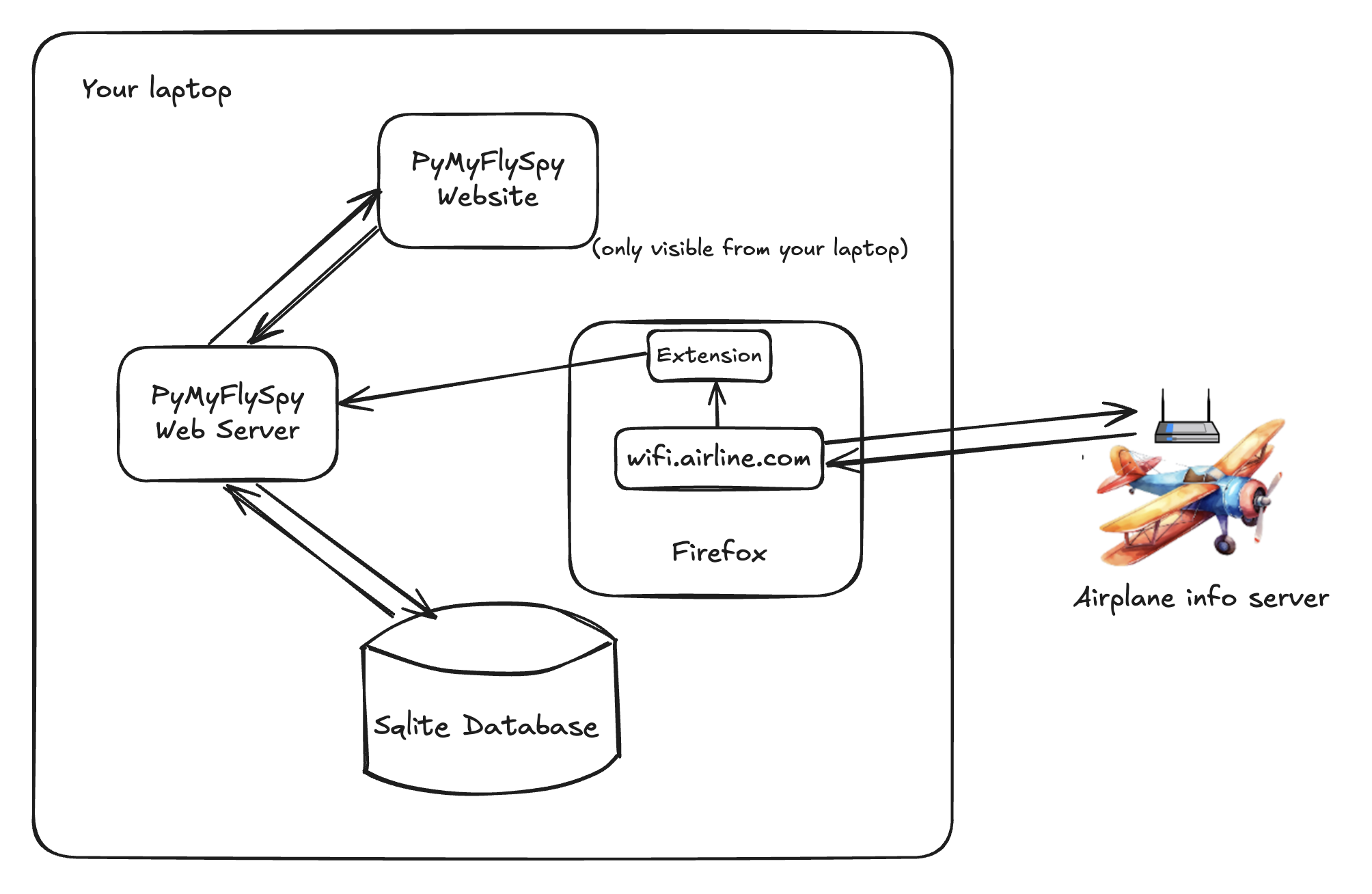

The system is very simple. It has 4 parts:

- Firefox Extension - reads flight info from the airline’s website and sends it to the PyMySkySpy web server

- Local web server - saves data that the extension sends to it, and makes it available to the frontend

- Sqlite Database - stores data

- Web frontend - displays data using maps and graphs

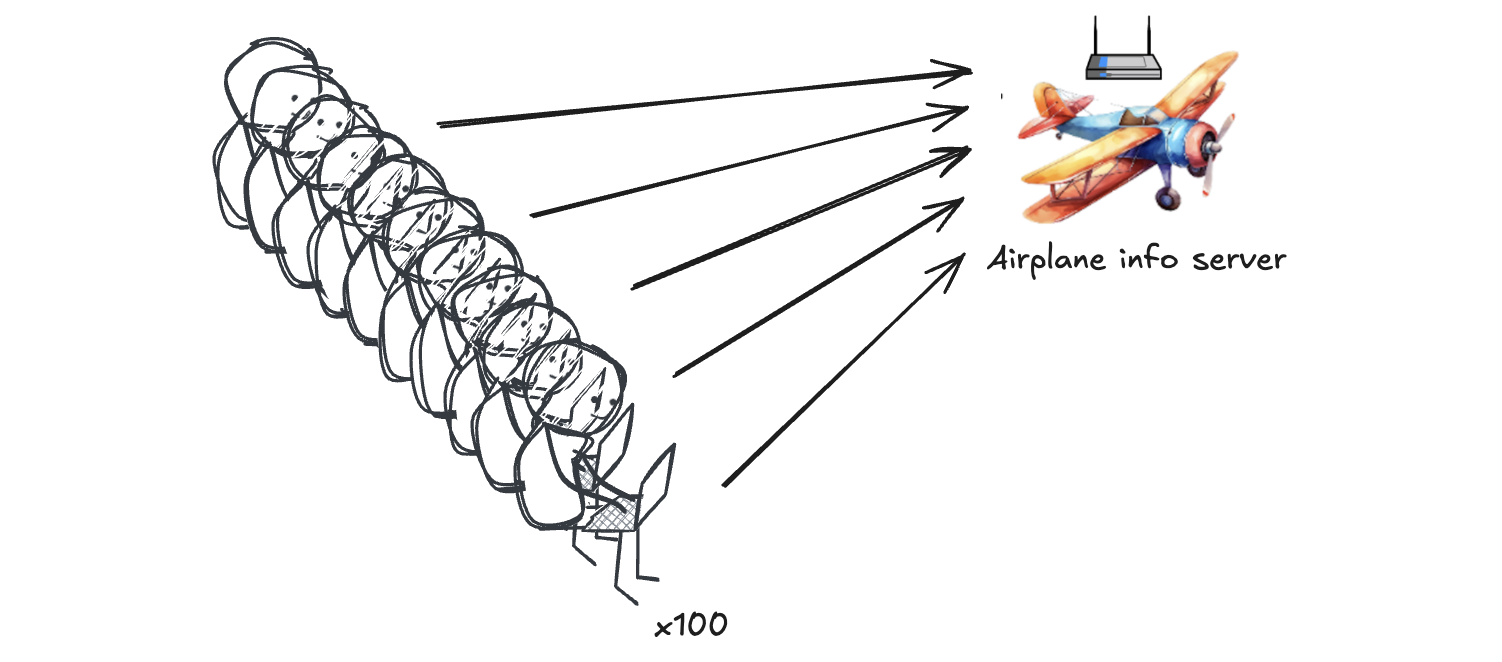

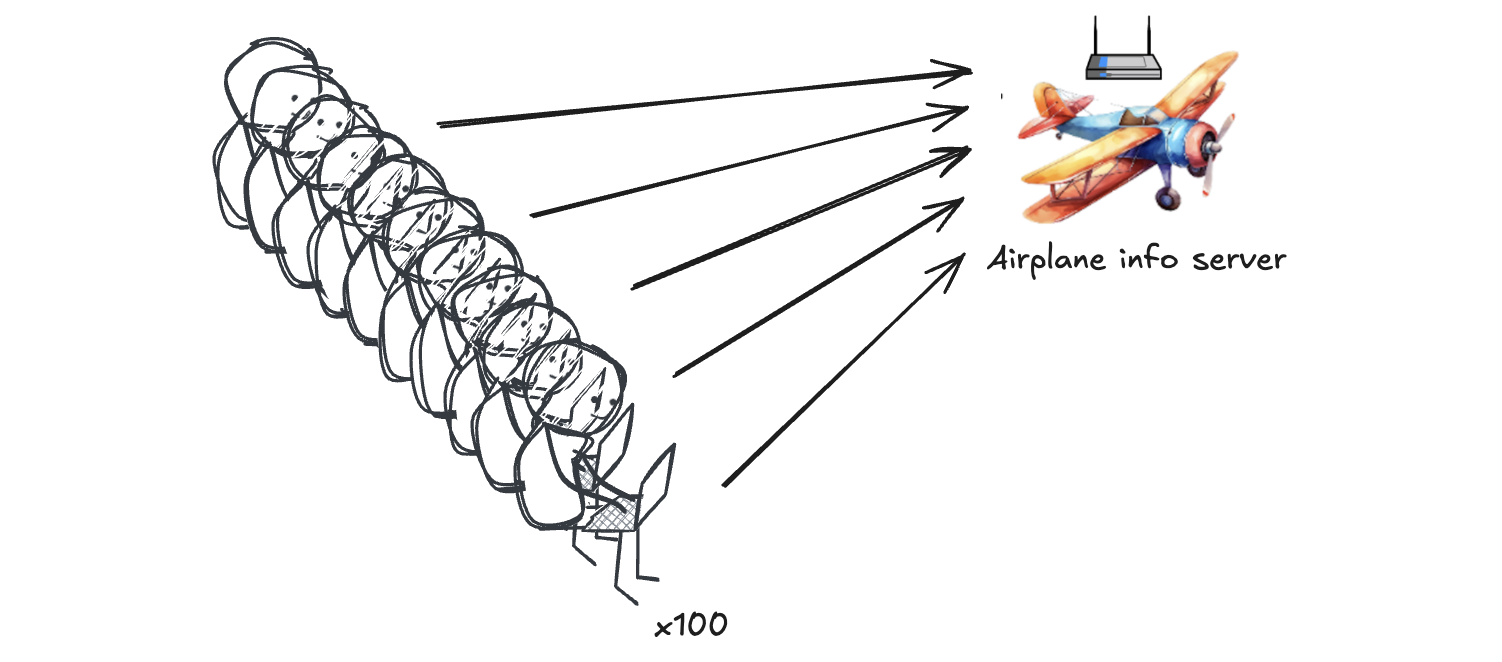

The one strange design choice I made was to use a Firefox Extension to read the flight data, instead of writing a scraper that makes its own data requests directly. Scraping the information like this would have been easier and more flexible, as well as completely harmless. Hundreds of people were already connected to the wifi, and the airline’s own landing page hits the /info endpoint once every couple of seconds. Adding one more request from a scraper would have been entirely safe.

However, I’m sure that airlines would rather people didn’t poke around at their onboard servers, even if those people are very careful and well-intentioned and handsome. To make sure I didn’t irritate them, I came up with an even more judicious approach.

Instead of scraping the data endpoint, I wrote a Firefox Extension. The extension sits there while the airline’s wi-fi landing page requests the latest data from the /info endpoint, just like normal, every few seconds. The extension peeks at the data that’s returned; sends the data to the PyMyFlySpy web server; and finally the web server writes it to the PyMyFlySpy database, to serve to the web frontend. Using a Firefox Extension like this means that PyMyFlySpy never interacts with the plane’s info server directly. This means that PyMyFlySpy can provably never harm the server.

I had to write the extension for Firefox instead of Chrome, because Chrome is in the process of reducing extensions’ ability to interact with requests made by a website (like requests made to the /info endpoint). In particular, Chrome is going to prevent extensions from easily reading the responses to HTTP requests made by a website, which would prevent the PyMyFlySpy from reading the data returned by the /info endpoint. As far as I can tell these restrictions are half for security reasons, and half to make it harder to develop adblockers. Either way, PyMyFlySpy requires Firefox.

Future work - event subscriptions

PyMySkySpy gives us programmatic access to data about our flight. It would be fun to use this to trigger events, like:

- “For the first half of the flight, only let me open the big report that I need to finish by 5pm today.”

- “When our location is within 10 miles of the Grand Canyon, send the kids a Slack message to look out the window. Also send me a Slack message to bug them to look out the window.”

- “If our altitude drops by more than 300ft in 1 second then play a reassuring but really quite urgent sound on all of my devices.”

Next holiday, perhaps.

The flight home

Our flight home was in the late afternoon. We shuffled on board and took off. I pulled out my laptop, connected to the wi-fi, and booted up PyMySkySpy. I turned to my son to show him where we were. I’d shown him the prototype every day for the last week and I though he seemed to be somewhere between “tolerant” and “mildly interested.” But he’d already fallen asleep. I took some screenshots to show him later.

I spent the next few hours monitoring and debugging the recorder to make sure that it stayed up. My two-year-old screamed the whole flight and kept trying to throw himself on the floor. I made supportive faces at my wife across the aisle and pretended to offer to take him, but she shook her head. She knew that this was important.

I watched the graphs. Temperature within normal range. Wind speed stable. Suddenly our altitude dropped by a fifty feet. I wondered if I should tell the pilots. I decided that they probably had it under control. I kept watching, just in case.

“Where are we daddy?” asked my five-year-old.

“We’ll land in about an hour,” I said.

“No I mean where are we? Are we flying over Italy yet?”

I wasn’t sure. Our flight was short and cheap and the seats didn’t have TV screens in the headrests. I looked around. I noticed a sticker encouraging me to connect to the in-flight wi-fi. That would do it, I thought. A site like FlightRadar would answer my little man’s question, down to the nearest few meters.

But unfortunately for him I’m the creator of PySkyWiFi (“completely free, unbelievably stupid wi-fi on long-haul flights”). Not paying for airplane internet is kind of my signature move. We’d need a different, offline strategy.

I had a think. When you connect to an airplane wi-fi network, you’re usually met with a payment page where you can purchase access to the internet. The page also usually gives you the same flight information that you’d find in the back of your headrest, like speed, direction, and estimated flight length. Perhaps it would have a map as well, I thought.

I pulled out my laptop, connected to the network, and loaded up the payment page. It did indeed show our wind speed, direction, and estimated time of arrival. But no map.

(It didn’t occur to me to screenshot the page so here’s an artist’s impression)

“Maybe the server that’s sending us this data is actually also sending us our location, but the web page isn’t displaying it,” I thought. I opened up the Chrome developer tools. I saw that my browser was making regular requests to a /info endpoint.

I clicked on one of the requests. This /info endpoint was indeed sending us a huge pile of data, including fields for ground_speed, wind_speed, and estimated_arrival_time. At the bottom of the response I noticed fields for latitude and longitude. My heart leapt. But then I looked closer. They were both null. Aerofoiled.

This looked like the end of the line. I was about to give up and tell my son that we were somewhere just north of Italy, probably…Europe somewhere. But then I was hit by two fantastic ideas.

Fantastic idea number 1: the /info endpoint didn’t tell us our location, but it did tell us our precise, regularly-updated speed and direction. On our flight home I could track and save our speed and direction every second or so for the whole flight. I could use this information to estimate how far we had traveled in each second, and in which direction. I could dynamically calculate our position by starting at our airport’s co-ordinates, then adding on each second’s step.

Fantastic idea number 2: even if I had been able to find our latitude and longitude in the /info response, it wouldn’t have meant much to either me or my son. However, I could build a web app that ran on my laptop and showed us our dynamically calculated position on a map, in real time. The app could have automatically updating graphs of our ETA, wind direction, speed, altitude, and so on. Ooh and an interface for running arbitrary queries against the data. And event callbacks to allow me to programmatically trigger code based on flight info (“when our ETA is 2 hours exactly, block my access to netflix.com and open the latest draft of my unfinished novel”). My son would know where he was. I’d be a Good Dad.

I decided to call the app PyMyFlySpy in order to give it some brand association with PySkyWiFi, my airplane-related project. I couldn’t wait to get started. Unfortunately right now I was wedged in between a five-year-old and a two-year-old and we were all terrible at JavaScript. I waited, impatiently.

PyMyFlySpy

Eventually we landed. I built PyMyFlySpy during our holiday, over late evenings and one or two derelict afternoons while the rest of my family did normal-person fun things. I couldn’t figure out whether it was bad manners to use your laptop in artisanal Italian coffee shops, or which of them had wi-fi, so to my eternal shame I googled “starbucks near me” and planted myself in a corner with a skinny mochachino and typed away.

I finished PyMyFlySpy the day before we left. The code is available on GitHub and it’s easy to setup and run. It even has a “dummy” mode that allows you to demo it without being inside a plane, using a made-up flight.

Here’s what PyMyFlySpy can do:

Maps and graphs

PyMySkySpy shows a map of your flightpath so far. It also shows your current flight metrics and how these metrics have changed over the course of your flight. It does this for all data available from the in-flight wi-fi, even data that isn’t usually displayed on the website or headrest screen. You can see exactly where you are and feel a bit like a pilot.

Query interface

PyMySkySpy saves all the data that it records to a database. Its UI has a page that allows you to write queries against the data to answer questions like “what’s our maximum speed so far, and when did we hit it?” or “how fast was the wind during that turbulence we just went through?”

I’m not claiming that this is hugely useful, but I do think it’s cool.

Multi-airline support

Different airlines have different wi-fi systems. A recorder for a JetBlue flight won’t work on AirFrance. Fortunately, PyMySkySpy allows you to easily add and use recorders for different airlines. You just have to load up their wi-fi landing page, open your browser’s developer tools, and figure out how to parse their page’s data like I did above. Then you add your new code to the PyMySkySpy config, and tell the recorder to use it. Everything else continues to work just the same.

System design

The system is very simple. It has 4 parts:

- Firefox Extension - reads flight info from the airline’s website and sends it to the PyMySkySpy web server

- Local web server - saves data that the extension sends to it, and makes it available to the frontend

- Sqlite Database - stores data

- Web frontend - displays data using maps and graphs

The one strange design choice I made was to use a Firefox Extension to read the flight data, instead of writing a scraper that makes its own data requests directly. Scraping the information like this would have been easier and more flexible, as well as completely harmless. Hundreds of people were already connected to the wifi, and the airline’s own landing page hits the /info endpoint once every couple of seconds. Adding one more request from a scraper would have been entirely safe.

However, I’m sure that airlines would rather people didn’t poke around at their onboard servers, even if those people are very careful and well-intentioned and handsome. To make sure I didn’t irritate them, I came up with an even more judicious approach.

Instead of scraping the data endpoint, I wrote a Firefox Extension. The extension sits there while the airline’s wi-fi landing page requests the latest data from the /info endpoint, just like normal, every few seconds. The extension peeks at the data that’s returned; sends the data to the PyMyFlySpy web server; and finally the web server writes it to the PyMyFlySpy database, to serve to the web frontend. Using a Firefox Extension like this means that PyMyFlySpy never interacts with the plane’s info server directly. This means that PyMyFlySpy can provably never harm the server.

I had to write the extension for Firefox instead of Chrome, because Chrome is in the process of reducing extensions’ ability to interact with requests made by a website (like requests made to the /info endpoint). In particular, Chrome is going to prevent extensions from easily reading the responses to HTTP requests made by a website, which would prevent the PyMyFlySpy from reading the data returned by the /info endpoint. As far as I can tell these restrictions are half for security reasons, and half to make it harder to develop adblockers. Either way, PyMyFlySpy requires Firefox.

Future work - event subscriptions

PyMySkySpy gives us programmatic access to data about our flight. It would be fun to use this to trigger events, like:

- “For the first half of the flight, only let me open the big report that I need to finish by 5pm today.”

- “When our location is within 10 miles of the Grand Canyon, send the kids a Slack message to look out the window. Also send me a Slack message to bug them to look out the window.”

- “If our altitude drops by more than 300ft in 1 second then play a reassuring but really quite urgent sound on all of my devices.”

Next holiday, perhaps.

The flight home

Our flight home was in the late afternoon. We shuffled on board and took off. I pulled out my laptop, connected to the wi-fi, and booted up PyMySkySpy. I turned to my son to show him where we were. I’d shown him the prototype every day for the last week and I though he seemed to be somewhere between “tolerant” and “mildly interested.” But he’d already fallen asleep. I took some screenshots to show him later.

I spent the next few hours monitoring and debugging the recorder to make sure that it stayed up. My two-year-old screamed the whole flight and kept trying to throw himself on the floor. I made supportive faces at my wife across the aisle and pretended to offer to take him, but she shook her head. She knew that this was important.

I watched the graphs. Temperature within normal range. Wind speed stable. Suddenly our altitude dropped by a fifty feet. I wondered if I should tell the pilots. I decided that they probably had it under control. I kept watching, just in case.