Migrating bajillions of database records at Stripe

31 Aug 2015

There are roughly ten thousand bajillion (to the nearest bajillion) merchants registered with Stripe. We recently finished a Very Big Migration of Large Amounts Of Data between several database tables for every single one of them, without losing any of it, without any downtime, mis-reads or mis-writes, whilst running a system that is responsible for the transfer of squillions of dollars every single day.

This was conceptually relatively simple, but the devil and the ability to sleep at night is in the details. Here’s how we did it.

0. The principle.

At Stripe we have a Merchant table and an AccountApplication table. Every Merchant has an AccountApplication, and once upon a time these tables contained every single one of a merchant’s details. This included both trivial information like email_font_color and self_estimated_yearly_turnover, and very very important, legally-required “Know Your Customer” information like business_name and tax_id_number.

For the recent launch of Stripe Connect, we needed to build out a new system that would tell Connect Applications exactly what “KYC” information is currently required for each of their connected merchants. This is a complicated process that varies by country, business type and other factors. To make the new system as simple, modular and generally tractable as possible, we needed to extract all of these “KYC” fields into a single, seperate LegalEntity table.

If we could temporarily take down our entire system for a while, and if we were programming robots who never made anything remotely close to a mistake, we would simply turn off our servers, tell all of our merchants not to sell anything for a while, move all the data from the Merchant and AccountApplication tables to the LegalEntity table, convert all of our code to read and write to this new table, turn our servers on again, and give the all clear that the internet can start selling again.

But we obviously cannot take down our system at all. This means that during the time we are migrating all of this data, we are going to have ten thousand bajillion pesky users wanting to read and write new information. If we’re not careful then we could easily end up reading old data and failing to write new data. This would be Really Really Bad.

And we are not programming robots, and if we try and change many thousands of lines of code that touch every single part of our system all at once, at some point we are inevitably going to miss something. Instead of one enormous “pleaseworkpleaseworkpleaswork” change, we want to make a long series of many small changes so that we can easily A) monitor each small change in production for correctness, preferably “in the dark” alongside our old code and B) easily recover from any mistakes that we do make.

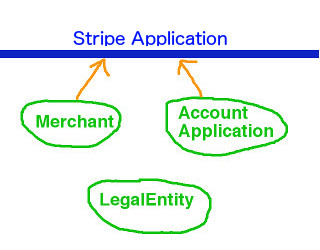

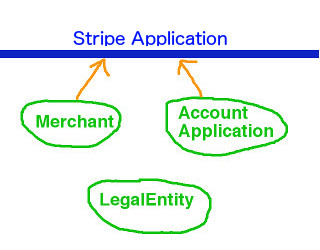

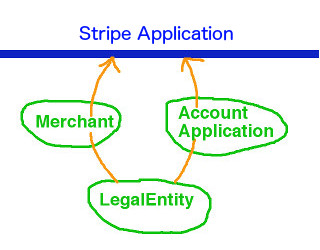

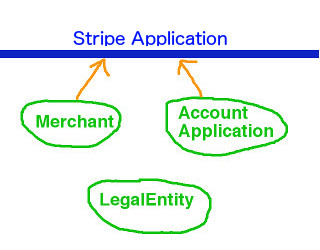

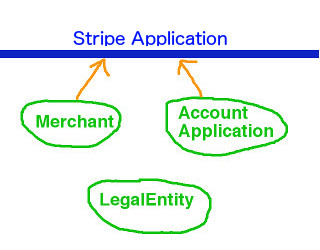

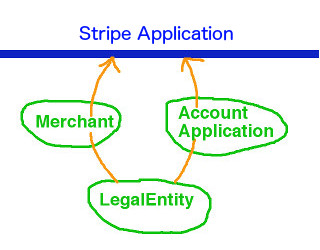

The entire migration is essentially a transition of data reading from:

to:

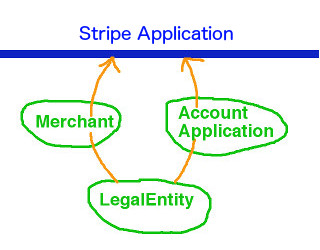

and data writing from:

to:

This is done in 4 phases:

- Migrate all old data to the LegalEntity. Use double-writing to make sure it stays in sync.

- Proxy all reads to the Merchant and AccountApplication through to the LegalEntity.

- Read and write all data to only the LegalEntity directly.

- Miscellaneous but surprisingly challenging cleanup.

Read on to find out both the nitty and the gritty details.

1. Data migration

1.1 Make the LegalEntity model

We start by making the LegalEntity model in our ORM, and the associated table in our database. So far it contains no data, and does absolutely nothing.

class LegalEntity

end

1.2 Start double-writing to the LegalEntity

We begin by double-writing all writes to the relevant Merchant and AccountApplication properties to the LegalEntity equivalent. For example, when we write to Merchant#owner_first_name, we also write to LegalEntity#first_name. Note that we have not yet migrated old data to the LegalEntity, so the Merchant and AccountApplication remain the source of truth.

With the utmost of care, we use some meta-programming magic:

class Merchant

# Each Merchant has a LegalEntity

prop :legal_entity, foreign: LegalEntity

def self.legal_entity_proxy(merchant_prop_name, legal_entity_prop_name)

# Redefine the Merchant setter method to also write to the LegalEntity

merchant_prop_name_set = :"#{merchant_prop_name}="

original_merchant_prop_name_set = :"original_#{merchant_prop_name_set}"

alias_method original_merchant_prop_name_set, merchant_prop_name_set if method_defined?(merchant_prop_name_set)

define_method(merchant_prop_name_set) do |val|

self.public_send(original_merchant_prop_name_set, val)

self.legal_entity.public_send(:"#{legal_entity_prop_name}=", val)

end

end

legal_entity_proxy :owner_first_name, :first_name

before_save do

# Make sure that we actually save our LegalEntity double-write.

# This "multi-save" can cause confusion and unnecessary database calls,

# but is a necessary evil and will be unwound later

self.legal_entity.save

end

end

merchant.owner_first_name = 'Barry'

merchant.save

merchant.legal_entity.first_name

# => Also 'Barry'

We let this run in production for a few days, and verify that the data is consistent between tables. If it is not then that we can debug and fix at our leisure, since the Merchant and AccountApplication tables are still the source of truth and we are not relying on the data in the LegalEntity for anything at this point.

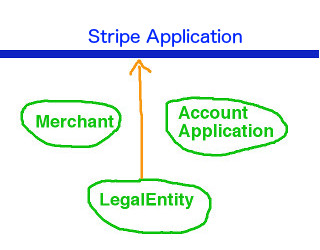

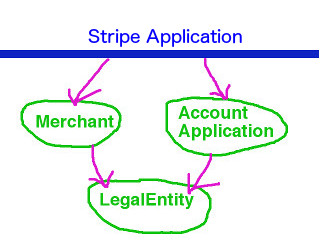

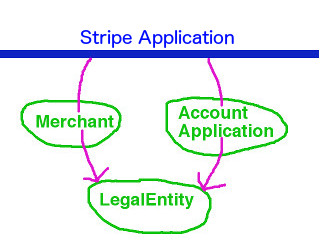

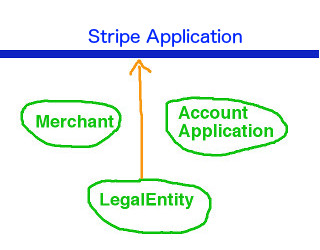

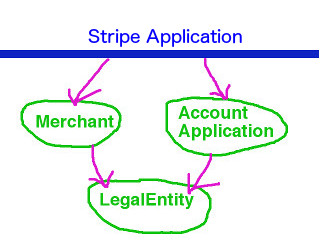

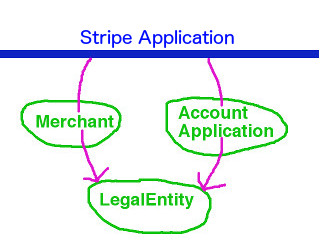

This updates our data-flows to:

Read:

Write:

1.3 Migrate old data to the LegalEntity

Next, we iterate through every single Merchant and AccountApplication record and migrate the relevant properties over to the LegalEntity. Our double-writing code ensures that whilst this (long-running) migration is in progress, we stay in sync even as data is added and updated.

We once again check that the relevant Merchant, AccountApplication and LegalEntity fields contain exactly the same data.

2. Start reading from the LegalEntity

2.1 Proxy reads to the Merchant/AccountApplication through to the LegalEntity

We are now very confident that the LegalEntity table is in sync with and just as reliable as the Merchant and AccountApplication tables. Carefully using some more meta-programming magic, we make all calls to eg. merchant.owner_first_name proxy through to read their data from the associated LegalEntity. We continue to write data to both tables and put this proxying behind a feature flag. This is a simple flag that can be instantly toggled from a UI. When deciding whether to read data from the LegalEntity or from one of our old models, we first check to see if the feature flag is set to “on”. This means that if we discover an inconsistency or other error we can instantly flip the feature flag off and switch back to reading directly from the Merchant table whilst we debug.

class Merchant

prop :legal_entity, foreign: LegalEntity

def self.legal_entity_proxy(merchant_prop_name, legal_entity_prop_name)

#

# UPDATED: Now we also redefine the Merchant getter method to read from the LegalEntity

#

alias_method :"original_#{merchant_prop_name}", merchant_prop_name if method_defined?(merchant_prop_name)

define_method(merchant_prop_name) do

self.legal_entity.public_send(legal_entity_prop_name)

end

# We continue to write to both tables for safety

merchant_prop_name_set = :"#{merchant_prop_name}="

original_merchant_prop_name_set = :"original_#{merchant_prop_name_set}"

alias_method original_merchant_prop_name_set, merchant_prop_name_set if method_defined?(merchant_prop_name_set)

define_method(merchant_prop_name_set) do |val|

self.public_send(original_merchant_prop_name_set, val)

self.legal_entity.public_send(:"#{legal_entity_prop_name}=", val)

end

end

legal_entity_proxy :owner_first_name, :first_name

before_save do

self.legal_entity.save

end

end

merchant.owner_first_name

# => calls legal_entity.first_name, which should be the same as Merchant#owner_first_name anyway

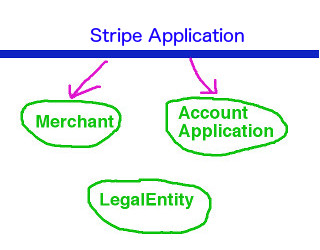

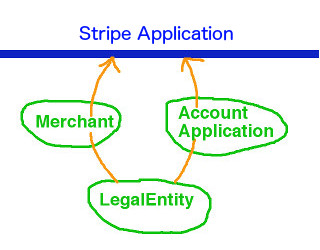

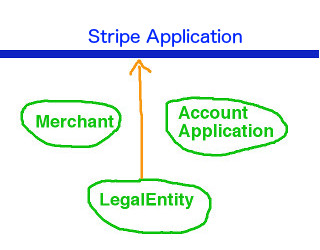

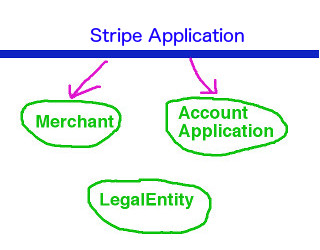

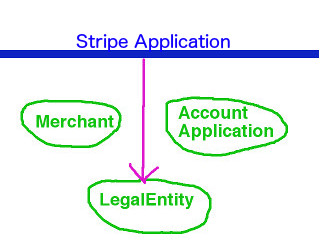

This updates our data-flows to:

Read:

Write:

We let this code run in production for a few days, stay vigilant for any strange bug reports, and check regularly that all of our data continues to be in sync. The LegalEntity is now the source of truth.

2.2 Stop writing to the Merchant/AccountApplication altogether

We are now reading all of our data from the LegalEntity, and are no longer using the data stored in the corresponding Merchant or AccountApplication fields. Once we are sufficiently confident in our setup, we remove the Merchant and AccountApplication fields and database columns altogether and stop writing to them. merchant.owner_first_name now both reads and writes only to the LegalEntity, and the Merchant no longer has a real owner_first_name property.

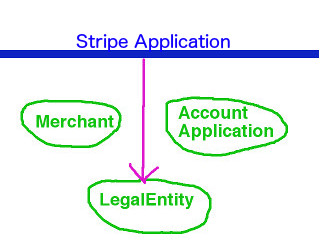

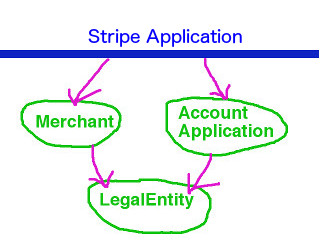

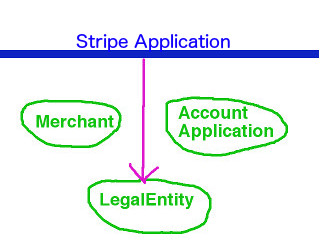

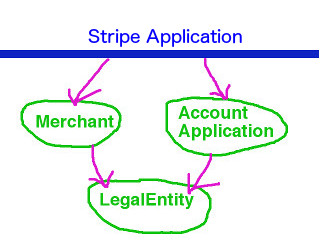

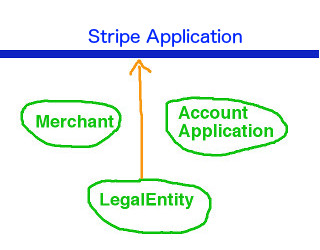

This updates our data-flows to:

Read:

Write:

Our data is now fully migrated, and all that remains is to clean up our codebase to reflect this. We are still making multiple database calls every time we save our objects, and we are still relying on a non-obvious chain of meta-programming and indirection to proxy and glue everything together.

3. Read and write to the LegalEntity directly

3.1 Grep grep grep grep

This step requires us to be particularly methodical, and is best carried out from within some kind of isolation tank or spiritual mountain retreat. For each Merchant or AccountApplication property that is being proxied through to the LegalEntity, we grep the entire codebase for every single read or write of it, and change to read or write to the LegalEntity directly. For example:

merchant.owner_first_name = 'Barry'

becomes:

legal_entity.first_name = 'Barry'

We touch a lot of unfamiliar code that we have never seen before, so we are thankful for our extensive and reliable test suite and ask the people with the most context on the code we are updating to review our changes.. We migrate each property in a separate pull request that can be reviewed, monitored and reverted (if necessary) individually.

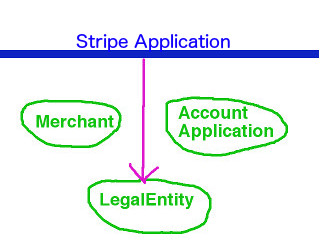

This updates our data-flows to:

Read:

Write:

3.2 Use logging to track down stragglers

Whilst we are of course hyper-focussed programming demigods, there is nonetheless a small chance that we may miss the odd call to Merchant#owner_favorite_type_of_fruit (NB we are not legally required to collect this information outside of New Mexico). It is also very probable that our blissfully unaware colleagues may have added new calls to the very fields we are trying to remove. This is fine, since these calls will still correctly proxy through to the relevant LegalEntity properties.

However, in order to make sure we have tracked down everything before we turn off read-proxying completely, we log whenever a deprecated Merchant or AccountApplication field is accessed, and add in an assertion that will make tests fail whenever they are called (but will not throw errors in production).

class Merchant

prop :legal_entity, foreign: LegalEntity

def self.legal_entity_proxy(merchant_prop_name, legal_entity_prop_name)

alias_method :"original_#{merchant_prop_name}", merchant_prop_name if method_defined?(merchant_prop_name)

define_method(merchant_prop_name) do

#

# UPDATED: We add in logging

#

log.info('Deprecated method called')

self.legal_entity.public_send(legal_entity_prop_name)

end

merchant_prop_name_set = :"#{merchant_prop_name}="

original_merchant_prop_name_set = :"original_#{merchant_prop_name_set}"

alias_method original_merchant_prop_name_set, merchant_prop_name_set if method_defined?(merchant_prop_name_set)

define_method(merchant_prop_name_set) do |val|

#

# UPDATED: We add in logging

#

log.info('Deprecated method called')

self.legal_entity.public_send(:"#{legal_entity_prop_name}=", val)

end

end

end

We let this run in production, search our logs for 'Deprecated method called', and remove every instance we find.

3.3 Remove proxying altogether

Once our logging has been silent for for a suitable amount of time (say 2-7 days, depending on how paranoid we are), we remove the proxying layer altogether. All being well it is no longer being used and this should be a no-op, although we nonetheless remove proxying for one or small groups of properties at a time, rather than all of them at once. Just in case.

class Merchant

prop :legal_entity, foreign: LegalEntity

# REMOVED

#

# def self.legal_entity_proxy(merchant_prop_name, legal_entity_prop_name)

# # etc

# end

#

# legal_entity_proxy :owner_first_name, :first_name

before_save do

self.legal_entity.save

end

end

4. Stop multi-saving

4.1 Log where the multi-save is needed

All of our data is now being read and written directly to the LegalEntity. However, we are still chaining saves through our models, and saving the Merchant still secretly saves the LegalEntity (see the above before_save block). We will most likely have a large number of slightly obtuse looking sections along the lines of:

legal_entity.first_name = 'Barry'

merchant.save

This still works, but is not a tidy state of affairs. We would like to remove the confusing and obfuscating save-chaining and explicitly save everything we need to save ourselves. We therefore log all places where our merchant.save (or whatever) is also actually causing fields on the legal_entity to be changed (as above). We update our before_save blocks to look like:

class Merchant

prop :legal_entity, foreign: LegalEntity

before_save do

# Our ORM's implementation of "dirty" fields

unless self.legal_entity.updated_fields.empty?

self.legal_entity.save

log.info('Multi-saved an updated model')

end

end

end

We also add a feature flag to allow us to force multi-saving, even when there are apparently no updated fields. We can panic-turn this on if we believe that it is necessary.

4.2 Good Hunting

For the next few days, we search our logs for 'Multi-saved an updated model' to track down all places where saving the Merchant or AccountApplication is also responsible for saving new data on the LegalEntity. We save the LegalEntity ourselves, just before saving the other model, which sets legal_entity.updated_fields to be empty, preventing our log-line from being hit.

legal_entity.first_name = 'Barry'

merchant.business_url = 'http://foobar.com'

merchant.save

will trigger our log-line, since merchant.save will also save the new LegalEntity#owner_name. It becomes:

legal_entity.first_name = 'Barry'

legal_entity.save

merchant.business_url = 'http://foobar.com'

merchant.save

which will not, since legal_entity has already saved itself. We add assertions in our before_save block that will make tests that rely on the multi-save to fail, and clean them up too.

4.3 Remove the multi-save

Once our log-line has stopped being triggered and we are confident that every model with updated data is correctly saving itself, we pull the final trigger and remove the multi-save. All of our data is where it is supposed to be, we are not proxying any reads or writes, and we are not using any meta-programming.

class Merchant

prop :legal_entity, foreign: LegalEntity

end

It is over. We feel human once again.

5. Conclusion

Throughout the entire migration, we never made a change that we didn’t have strong, empirical evidence to believe was correct. We were almost always making small, incremental updates that were never in danger of seriously breaking our system. This pattern of migrating data by double-writing to both the old and the new sources, then gradually switching over all of your reads to the new source and turning off the old one, is a very common and safe one.

On the other hand, by far the most awkward part of the process is “The Multi-Save”. Having an innocent merchant.save trigger saving multiple different models as well is Not Intuitive, and requires you to be very precise and clear that the LegalEntity object in memory you are updating is the same one that is being multi-saved. ORM’s are a wonderful thing, but can start to creak a little when you rely on them too much.

If you ever find yourself writing a single, enormous yolo-pull-request to migrate a very large amount of anything, think hard about whether it is possible to make the moment of deploying less pant-wettingly terrifying. If the answer is “no”, be sure to come up with your new fake identity and backstory for when you inevitably have to flee the country and start a new life in Brazil.

Thanks to Brian Krausz for devising the entire migration. Thanks also to Sandy Wu, Avi Itskovich, Maher Beg, Julia Evans, Tim Drinian and Darragh Buckley for reading and improving drafts of this post.

There are roughly ten thousand bajillion (to the nearest bajillion) merchants registered with Stripe. We recently finished a Very Big Migration of Large Amounts Of Data between several database tables for every single one of them, without losing any of it, without any downtime, mis-reads or mis-writes, whilst running a system that is responsible for the transfer of squillions of dollars every single day.

This was conceptually relatively simple, but the devil and the ability to sleep at night is in the details. Here’s how we did it.

0. The principle.

At Stripe we have a Merchant table and an AccountApplication table. Every Merchant has an AccountApplication, and once upon a time these tables contained every single one of a merchant’s details. This included both trivial information like email_font_color and self_estimated_yearly_turnover, and very very important, legally-required “Know Your Customer” information like business_name and tax_id_number.

For the recent launch of Stripe Connect, we needed to build out a new system that would tell Connect Applications exactly what “KYC” information is currently required for each of their connected merchants. This is a complicated process that varies by country, business type and other factors. To make the new system as simple, modular and generally tractable as possible, we needed to extract all of these “KYC” fields into a single, seperate LegalEntity table.

If we could temporarily take down our entire system for a while, and if we were programming robots who never made anything remotely close to a mistake, we would simply turn off our servers, tell all of our merchants not to sell anything for a while, move all the data from the Merchant and AccountApplication tables to the LegalEntity table, convert all of our code to read and write to this new table, turn our servers on again, and give the all clear that the internet can start selling again.

But we obviously cannot take down our system at all. This means that during the time we are migrating all of this data, we are going to have ten thousand bajillion pesky users wanting to read and write new information. If we’re not careful then we could easily end up reading old data and failing to write new data. This would be Really Really Bad.

And we are not programming robots, and if we try and change many thousands of lines of code that touch every single part of our system all at once, at some point we are inevitably going to miss something. Instead of one enormous “pleaseworkpleaseworkpleaswork” change, we want to make a long series of many small changes so that we can easily A) monitor each small change in production for correctness, preferably “in the dark” alongside our old code and B) easily recover from any mistakes that we do make.

The entire migration is essentially a transition of data reading from:

to:

and data writing from:

to:

This is done in 4 phases:

- Migrate all old data to the LegalEntity. Use double-writing to make sure it stays in sync.

- Proxy all reads to the Merchant and AccountApplication through to the LegalEntity.

- Read and write all data to only the LegalEntity directly.

- Miscellaneous but surprisingly challenging cleanup.

Read on to find out both the nitty and the gritty details.

1. Data migration

1.1 Make the LegalEntity model

We start by making the LegalEntity model in our ORM, and the associated table in our database. So far it contains no data, and does absolutely nothing.

class LegalEntity

end

1.2 Start double-writing to the LegalEntity

We begin by double-writing all writes to the relevant Merchant and AccountApplication properties to the LegalEntity equivalent. For example, when we write to Merchant#owner_first_name, we also write to LegalEntity#first_name. Note that we have not yet migrated old data to the LegalEntity, so the Merchant and AccountApplication remain the source of truth.

With the utmost of care, we use some meta-programming magic:

class Merchant

# Each Merchant has a LegalEntity

prop :legal_entity, foreign: LegalEntity

def self.legal_entity_proxy(merchant_prop_name, legal_entity_prop_name)

# Redefine the Merchant setter method to also write to the LegalEntity

merchant_prop_name_set = :"#{merchant_prop_name}="

original_merchant_prop_name_set = :"original_#{merchant_prop_name_set}"

alias_method original_merchant_prop_name_set, merchant_prop_name_set if method_defined?(merchant_prop_name_set)

define_method(merchant_prop_name_set) do |val|

self.public_send(original_merchant_prop_name_set, val)

self.legal_entity.public_send(:"#{legal_entity_prop_name}=", val)

end

end

legal_entity_proxy :owner_first_name, :first_name

before_save do

# Make sure that we actually save our LegalEntity double-write.

# This "multi-save" can cause confusion and unnecessary database calls,

# but is a necessary evil and will be unwound later

self.legal_entity.save

end

end

merchant.owner_first_name = 'Barry'

merchant.save

merchant.legal_entity.first_name

# => Also 'Barry'

We let this run in production for a few days, and verify that the data is consistent between tables. If it is not then that we can debug and fix at our leisure, since the Merchant and AccountApplication tables are still the source of truth and we are not relying on the data in the LegalEntity for anything at this point.

This updates our data-flows to:

Read:

Write:

1.3 Migrate old data to the LegalEntity

Next, we iterate through every single Merchant and AccountApplication record and migrate the relevant properties over to the LegalEntity. Our double-writing code ensures that whilst this (long-running) migration is in progress, we stay in sync even as data is added and updated.

We once again check that the relevant Merchant, AccountApplication and LegalEntity fields contain exactly the same data.

2. Start reading from the LegalEntity

2.1 Proxy reads to the Merchant/AccountApplication through to the LegalEntity

We are now very confident that the LegalEntity table is in sync with and just as reliable as the Merchant and AccountApplication tables. Carefully using some more meta-programming magic, we make all calls to eg. merchant.owner_first_name proxy through to read their data from the associated LegalEntity. We continue to write data to both tables and put this proxying behind a feature flag. This is a simple flag that can be instantly toggled from a UI. When deciding whether to read data from the LegalEntity or from one of our old models, we first check to see if the feature flag is set to “on”. This means that if we discover an inconsistency or other error we can instantly flip the feature flag off and switch back to reading directly from the Merchant table whilst we debug.

class Merchant

prop :legal_entity, foreign: LegalEntity

def self.legal_entity_proxy(merchant_prop_name, legal_entity_prop_name)

#

# UPDATED: Now we also redefine the Merchant getter method to read from the LegalEntity

#

alias_method :"original_#{merchant_prop_name}", merchant_prop_name if method_defined?(merchant_prop_name)

define_method(merchant_prop_name) do

self.legal_entity.public_send(legal_entity_prop_name)

end

# We continue to write to both tables for safety

merchant_prop_name_set = :"#{merchant_prop_name}="

original_merchant_prop_name_set = :"original_#{merchant_prop_name_set}"

alias_method original_merchant_prop_name_set, merchant_prop_name_set if method_defined?(merchant_prop_name_set)

define_method(merchant_prop_name_set) do |val|

self.public_send(original_merchant_prop_name_set, val)

self.legal_entity.public_send(:"#{legal_entity_prop_name}=", val)

end

end

legal_entity_proxy :owner_first_name, :first_name

before_save do

self.legal_entity.save

end

end

merchant.owner_first_name

# => calls legal_entity.first_name, which should be the same as Merchant#owner_first_name anyway

This updates our data-flows to:

Read:

Write:

We let this code run in production for a few days, stay vigilant for any strange bug reports, and check regularly that all of our data continues to be in sync. The LegalEntity is now the source of truth.

2.2 Stop writing to the Merchant/AccountApplication altogether

We are now reading all of our data from the LegalEntity, and are no longer using the data stored in the corresponding Merchant or AccountApplication fields. Once we are sufficiently confident in our setup, we remove the Merchant and AccountApplication fields and database columns altogether and stop writing to them. merchant.owner_first_name now both reads and writes only to the LegalEntity, and the Merchant no longer has a real owner_first_name property.

This updates our data-flows to:

Read:

Write:

Our data is now fully migrated, and all that remains is to clean up our codebase to reflect this. We are still making multiple database calls every time we save our objects, and we are still relying on a non-obvious chain of meta-programming and indirection to proxy and glue everything together.

3. Read and write to the LegalEntity directly

3.1 Grep grep grep grep

This step requires us to be particularly methodical, and is best carried out from within some kind of isolation tank or spiritual mountain retreat. For each Merchant or AccountApplication property that is being proxied through to the LegalEntity, we grep the entire codebase for every single read or write of it, and change to read or write to the LegalEntity directly. For example:

merchant.owner_first_name = 'Barry'

becomes:

legal_entity.first_name = 'Barry'

We touch a lot of unfamiliar code that we have never seen before, so we are thankful for our extensive and reliable test suite and ask the people with the most context on the code we are updating to review our changes.. We migrate each property in a separate pull request that can be reviewed, monitored and reverted (if necessary) individually.

This updates our data-flows to:

Read:

Write:

3.2 Use logging to track down stragglers

Whilst we are of course hyper-focussed programming demigods, there is nonetheless a small chance that we may miss the odd call to Merchant#owner_favorite_type_of_fruit (NB we are not legally required to collect this information outside of New Mexico). It is also very probable that our blissfully unaware colleagues may have added new calls to the very fields we are trying to remove. This is fine, since these calls will still correctly proxy through to the relevant LegalEntity properties.

However, in order to make sure we have tracked down everything before we turn off read-proxying completely, we log whenever a deprecated Merchant or AccountApplication field is accessed, and add in an assertion that will make tests fail whenever they are called (but will not throw errors in production).

class Merchant

prop :legal_entity, foreign: LegalEntity

def self.legal_entity_proxy(merchant_prop_name, legal_entity_prop_name)

alias_method :"original_#{merchant_prop_name}", merchant_prop_name if method_defined?(merchant_prop_name)

define_method(merchant_prop_name) do

#

# UPDATED: We add in logging

#

log.info('Deprecated method called')

self.legal_entity.public_send(legal_entity_prop_name)

end

merchant_prop_name_set = :"#{merchant_prop_name}="

original_merchant_prop_name_set = :"original_#{merchant_prop_name_set}"

alias_method original_merchant_prop_name_set, merchant_prop_name_set if method_defined?(merchant_prop_name_set)

define_method(merchant_prop_name_set) do |val|

#

# UPDATED: We add in logging

#

log.info('Deprecated method called')

self.legal_entity.public_send(:"#{legal_entity_prop_name}=", val)

end

end

end

We let this run in production, search our logs for 'Deprecated method called', and remove every instance we find.

3.3 Remove proxying altogether

Once our logging has been silent for for a suitable amount of time (say 2-7 days, depending on how paranoid we are), we remove the proxying layer altogether. All being well it is no longer being used and this should be a no-op, although we nonetheless remove proxying for one or small groups of properties at a time, rather than all of them at once. Just in case.

class Merchant

prop :legal_entity, foreign: LegalEntity

# REMOVED

#

# def self.legal_entity_proxy(merchant_prop_name, legal_entity_prop_name)

# # etc

# end

#

# legal_entity_proxy :owner_first_name, :first_name

before_save do

self.legal_entity.save

end

end

4. Stop multi-saving

4.1 Log where the multi-save is needed

All of our data is now being read and written directly to the LegalEntity. However, we are still chaining saves through our models, and saving the Merchant still secretly saves the LegalEntity (see the above before_save block). We will most likely have a large number of slightly obtuse looking sections along the lines of:

legal_entity.first_name = 'Barry'

merchant.save

This still works, but is not a tidy state of affairs. We would like to remove the confusing and obfuscating save-chaining and explicitly save everything we need to save ourselves. We therefore log all places where our merchant.save (or whatever) is also actually causing fields on the legal_entity to be changed (as above). We update our before_save blocks to look like:

class Merchant

prop :legal_entity, foreign: LegalEntity

before_save do

# Our ORM's implementation of "dirty" fields

unless self.legal_entity.updated_fields.empty?

self.legal_entity.save

log.info('Multi-saved an updated model')

end

end

end

We also add a feature flag to allow us to force multi-saving, even when there are apparently no updated fields. We can panic-turn this on if we believe that it is necessary.

4.2 Good Hunting

For the next few days, we search our logs for 'Multi-saved an updated model' to track down all places where saving the Merchant or AccountApplication is also responsible for saving new data on the LegalEntity. We save the LegalEntity ourselves, just before saving the other model, which sets legal_entity.updated_fields to be empty, preventing our log-line from being hit.

legal_entity.first_name = 'Barry'

merchant.business_url = 'http://foobar.com'

merchant.save

will trigger our log-line, since merchant.save will also save the new LegalEntity#owner_name. It becomes:

legal_entity.first_name = 'Barry'

legal_entity.save

merchant.business_url = 'http://foobar.com'

merchant.save

which will not, since legal_entity has already saved itself. We add assertions in our before_save block that will make tests that rely on the multi-save to fail, and clean them up too.

4.3 Remove the multi-save

Once our log-line has stopped being triggered and we are confident that every model with updated data is correctly saving itself, we pull the final trigger and remove the multi-save. All of our data is where it is supposed to be, we are not proxying any reads or writes, and we are not using any meta-programming.

class Merchant

prop :legal_entity, foreign: LegalEntity

end

It is over. We feel human once again.

5. Conclusion

Throughout the entire migration, we never made a change that we didn’t have strong, empirical evidence to believe was correct. We were almost always making small, incremental updates that were never in danger of seriously breaking our system. This pattern of migrating data by double-writing to both the old and the new sources, then gradually switching over all of your reads to the new source and turning off the old one, is a very common and safe one.

On the other hand, by far the most awkward part of the process is “The Multi-Save”. Having an innocent merchant.save trigger saving multiple different models as well is Not Intuitive, and requires you to be very precise and clear that the LegalEntity object in memory you are updating is the same one that is being multi-saved. ORM’s are a wonderful thing, but can start to creak a little when you rely on them too much.

If you ever find yourself writing a single, enormous yolo-pull-request to migrate a very large amount of anything, think hard about whether it is possible to make the moment of deploying less pant-wettingly terrifying. If the answer is “no”, be sure to come up with your new fake identity and backstory for when you inevitably have to flee the country and start a new life in Brazil.

Thanks to Brian Krausz for devising the entire migration. Thanks also to Sandy Wu, Avi Itskovich, Maher Beg, Julia Evans, Tim Drinian and Darragh Buckley for reading and improving drafts of this post.