How to read

25 Jun 2018

Five years ago I realized that I remembered almost nothing about most books that I read. I was reading all kinds of non-fiction - pop-psychology, pop-economics, pop-sociology, you name it - and felt like quite the polymath auto-didact. But one day, after I had finished blathering at a friend about how much I had enjoyed Thinking, Fast and Slow, they asked for a quick summary of the book’s overall thesis. I thought for a while, mumbled something about System 1 and System 2 and how I had only really read it for background knowledge, and adroitly changed the subject. As I was falling asleep that night it occurred to me that calling yourself an auto-didact doesn’t mean you actually know anything.

People laugh about how they don’t remember anything they learned in school. If you went to college then you probably haven’t used anything you learned there for quite some time, and have rationalized those years as something between a valuable lesson in learning how to think and a stupid but required passport to professionalism. I know that Pauli had an Exclusion Principle, but I could not tell you anything about who he was excluding or why. We generally seem to be OK with this.

As adults we read non-fiction books because they are fun, and because we want to know and remember the things inside them. However, it’s not surprising that we don’t remember much about what we read. Learning comes from repetition, and few people have occasion to think about capital-income ratios after finishing Capital In The Twenty-First Century. Even fewer spend much time immersed in black holes post-A Brief History of Time.

One completely valid way to deal with this fact is to decide that you are fine with it. Reading Manufacturing Consent is an enjoyable experience and worth doing for its own sake; you don’t want to be viewing all of your leisure activities through the lens of a strict cost-benefit analysis. You don’t care how much of Judge Judy you remember, and Noam Chomsky doesn’t get any special treatment. I should note that I have not actually read any books by Noam Chomsky, and I chose him as an example for reasons of intellectual signaling.

I’m currently trying to learn a lot about economics. I care a lot about this project, and find it sufficiently compelling that I’m willing to spend my limited reading time for it in a way that optimizes for learning over fun. I’ve evolved a system to help me remember more of what I read. It’s proven quite successful, and has won me such plaudits as “Where did you regurgitate all that from?” and “Well someone clearly just read ‘Why Nations Fail’”. It’s obviously completely made up and not the result of years of (or indeed any) scientific verification, but I have found it to be effective. Here’s a brief summary.

The basic idea

Learning comes from repetition, but books are long and verbose and not designed with this in mind. You can get a macro, high-level form of repetition by reading multiple books about the same topic, but even this doesn’t guarantee that you will remember the specific things that you want to or how it all hangs together.

To try and get more reps in, I think that books should be read in two phases:

- Read and annotate the book in a way that makes it easy to scan and digest once you have finished

- Once you have finished the book, make a “writeup”. This involves summarizing the book, doing further research and making flashcards (using Anki)

The writeup usually takes between one and four hours, and it serves three functions:

- It is a single, big repetition of the entire book

- It distills the important parts of the book into flashcards that you can keep repeating forever

- It gives you a condensed summary of the contents of a book and what you thought of it that you can refer back to

That said, you do have to start by actually doing some reading.

1. Reading the book

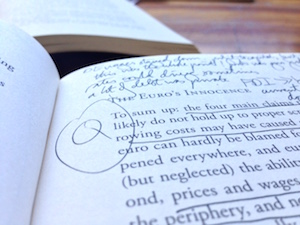

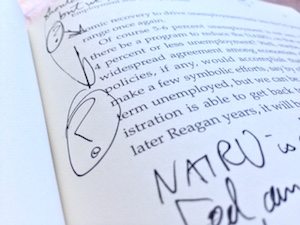

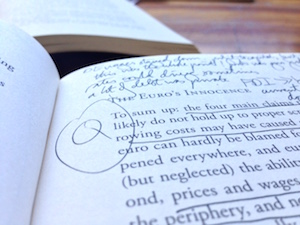

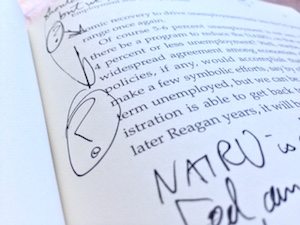

Always read with a pen. Scribbling over a book makes your actual reading more interactive and effective, but it also, more importantly, makes it much easier to create a writeup. With good annotations to guide you, scanning and summarizing a book for a writeup becomes a matter of collecting and actioning the clear hints that you have already left yourself.

The most straightforward and fundamental form of annotation is underlining. When a sentence, word or section catches your eye, put a big line under it. But we can do better than this. Make a note of why it caught your eye and what (if anything) you want to do with it. Is it a standalone fact that you want to remember? Is it an interesting lead for future research? Is it just a nice sentence, or a critical point that brings together the last ten pages?

I find that I can answer these questions using a small set of symbols:

Q

add this fact as a flashcard during the writeup

?

add this point as a flashcard during the writeup after doing some extra research

r?

Research this more

*

important point. Probably too broad to frame as a flashcard, but should be noted down in the Summary section of the writeup

…

this is complicated - think about it some more during the writeup

lol

nice quote - copy it down during the writeup and add to the universal "nice quotes" list. (I started using this symbol just for funny quotes, but then it evolved to signify all types of nice quotes. This has lead to a stack of evidence that will no doubt one day come to haunt me in court - "With his heart falling into a black abyss, Thomas pulled the trigger" LOL)

I also have a few symbols I use as shorthand for common notes:

orly

I don’t believe you

R

section that is particularly relevant if you’re planning on

writing

a

review. Probably contains something very good or very stupid

In addition, write your own longform sentences in the margins, with big arrows pointing at the section of the text they are referring to. Use them to:

- Rephrase or copy out verbatim important points

- “Poor EU countries pissed that they had to bailout richer Greece and fund their seniors’ lavish pensions”

- Write down any additional thoughts or connections that come to mind

- “I guess that bad things will happen if you over-estimate the power of your risk management models, no matter how good those models are”

- Write down any questions you have that the author hasn’t answered. Put the question mark in a square (see below)

- “Why did small economies want to join the Euro?”

These handwritten notes force you to engage more with what you are reading and will form the basis of the Summary section of your writeup. Finally, at the end of each chapter, flip back through it and scribble down a quick outline of what was in it. Don’t stop a reading session at the end of a chapter without writing the summary - if you don’t do it straightaway then you never will.

Once you have finished the book and are armed with symbols, sentences, summaries and some understanding of what you have just read, you are ready to begin consolidating your new knowledge in the writeup.

2. The writeup

The best time to start (and ideally finish) a writeup is the same day, or at most the day after you finish a book and the knowledge is still fresh in your mind and ready for repetition. Starting a writeup is much harder work than just moving on to the next book on your list, so it’s important to keep up momentum.

Begin your writeup with a template. I use one with headings for:

- Reviews

- Summary

- Quotes

- Questions

- My thoughts

Start by reading reviews and making brief notes on them. Next, thumb through the book and sweep up all of the annotations that you left for yourself. The bulk of this should be a stream of consciousness summary (written in the “Summary” section), guided by the points in the book that you either put a big * next to or wrote out yourself in longhand in the margins. I distinguish between notes that are coming straight from the text and those that are my interpretation of it by adding an arrow (=>) before the latter. I use quotation marks to signify a point that the author makes but that I don’t necessarilly agree with. You can add chapter headings and the occasional page number to help map from your notes back to the relevant section of the book if you ever need to.

“These affluent Democrats do not give a damn about inequality except as an election year slogan” (p92)

=> This is SUCH a strong statement - how does he know?

As well as writing a Summary, you should:

- Add each nice quote (marked in the book with a lol) to the “Quotes” section

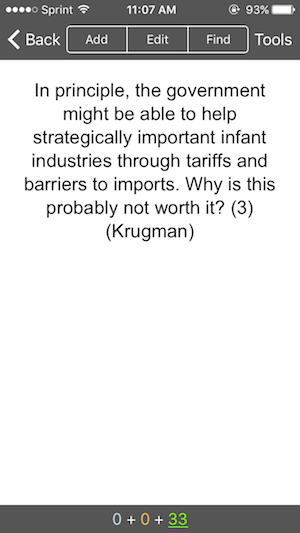

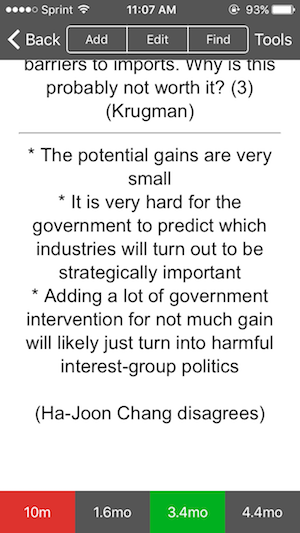

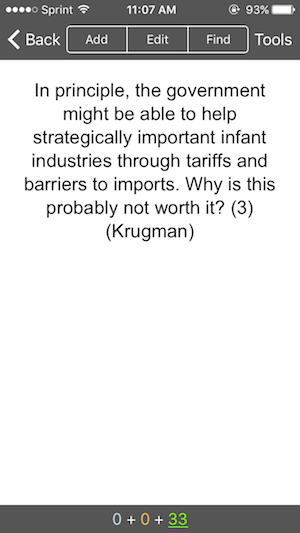

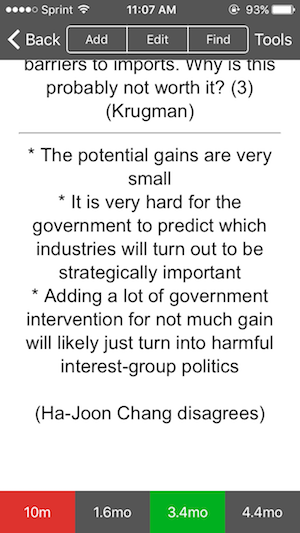

- Add each point to remember (marked with a Q) as a flashcard in Anki

- Add each point to research (marked with a ?) to the “Questions” section

After this, go back through your list of “Questions”, researching each one and making more flash cards. If you feel so moved then you can finish with a stream of consciousness of your overall reaction to the book in the “Thoughts” section. I also like to copy the list of “Quotes” into a master list of nice snippets, with a note of where they came from.

Everyone should keep a pile of aphorisms lying around - you never know when you’ll need one.

- Robert Heaton

Conclusion

If you follow this process and keep up with reviewing your flashcards, you will remember more of what you read. You can also find other ways to increase your reps. Find people to yammer at about what you are learning. If my experience if anything to go by then my wife would be very happy to talk to you, especially if you remember her father’s birthday. If you can think of something coherent to say about a book, write a review. If a book was good enough then read it again a year later (I have not done this very often).

On the other hand, if a book was boring or shallow then you don’t have to spend any more time on it. If you decide that you don’t care about remembering any of what you just read, don’t bother writing it up and just move onto a better book. If you want to read a book as “general background” and not spend too much time on it, then whilst I think you’re probably deceiving yourself somehow, that’s still totally fine with me. I listen to several hours of podcasts a week and feel good if I remember the name of one senator and the rough state of the Malaysian economy according to some woman whose name I don’t recall. But I am fine with this - I like the presenters’ voices and maybe there is such a thing as “general background” after all.

I do think that the most important thing is being honest with yourself. If you’re reading purely for fun, go and have as much fun as you possibly can and never look back. But if you’re reading for knowledge, be aware that this is quite a different thing.

Five years ago I realized that I remembered almost nothing about most books that I read. I was reading all kinds of non-fiction - pop-psychology, pop-economics, pop-sociology, you name it - and felt like quite the polymath auto-didact. But one day, after I had finished blathering at a friend about how much I had enjoyed Thinking, Fast and Slow, they asked for a quick summary of the book’s overall thesis. I thought for a while, mumbled something about System 1 and System 2 and how I had only really read it for background knowledge, and adroitly changed the subject. As I was falling asleep that night it occurred to me that calling yourself an auto-didact doesn’t mean you actually know anything.

People laugh about how they don’t remember anything they learned in school. If you went to college then you probably haven’t used anything you learned there for quite some time, and have rationalized those years as something between a valuable lesson in learning how to think and a stupid but required passport to professionalism. I know that Pauli had an Exclusion Principle, but I could not tell you anything about who he was excluding or why. We generally seem to be OK with this.

As adults we read non-fiction books because they are fun, and because we want to know and remember the things inside them. However, it’s not surprising that we don’t remember much about what we read. Learning comes from repetition, and few people have occasion to think about capital-income ratios after finishing Capital In The Twenty-First Century. Even fewer spend much time immersed in black holes post-A Brief History of Time.

One completely valid way to deal with this fact is to decide that you are fine with it. Reading Manufacturing Consent is an enjoyable experience and worth doing for its own sake; you don’t want to be viewing all of your leisure activities through the lens of a strict cost-benefit analysis. You don’t care how much of Judge Judy you remember, and Noam Chomsky doesn’t get any special treatment. I should note that I have not actually read any books by Noam Chomsky, and I chose him as an example for reasons of intellectual signaling.

I’m currently trying to learn a lot about economics. I care a lot about this project, and find it sufficiently compelling that I’m willing to spend my limited reading time for it in a way that optimizes for learning over fun. I’ve evolved a system to help me remember more of what I read. It’s proven quite successful, and has won me such plaudits as “Where did you regurgitate all that from?” and “Well someone clearly just read ‘Why Nations Fail’”. It’s obviously completely made up and not the result of years of (or indeed any) scientific verification, but I have found it to be effective. Here’s a brief summary.

The basic idea

Learning comes from repetition, but books are long and verbose and not designed with this in mind. You can get a macro, high-level form of repetition by reading multiple books about the same topic, but even this doesn’t guarantee that you will remember the specific things that you want to or how it all hangs together.

To try and get more reps in, I think that books should be read in two phases:

- Read and annotate the book in a way that makes it easy to scan and digest once you have finished

- Once you have finished the book, make a “writeup”. This involves summarizing the book, doing further research and making flashcards (using Anki)

The writeup usually takes between one and four hours, and it serves three functions:

- It is a single, big repetition of the entire book

- It distills the important parts of the book into flashcards that you can keep repeating forever

- It gives you a condensed summary of the contents of a book and what you thought of it that you can refer back to

That said, you do have to start by actually doing some reading.

1. Reading the book

Always read with a pen. Scribbling over a book makes your actual reading more interactive and effective, but it also, more importantly, makes it much easier to create a writeup. With good annotations to guide you, scanning and summarizing a book for a writeup becomes a matter of collecting and actioning the clear hints that you have already left yourself.

The most straightforward and fundamental form of annotation is underlining. When a sentence, word or section catches your eye, put a big line under it. But we can do better than this. Make a note of why it caught your eye and what (if anything) you want to do with it. Is it a standalone fact that you want to remember? Is it an interesting lead for future research? Is it just a nice sentence, or a critical point that brings together the last ten pages?

I find that I can answer these questions using a small set of symbols:

| Q | add this fact as a flashcard during the writeup |

|---|---|

| ? | add this point as a flashcard during the writeup after doing some extra research |

| r? | Research this more |

| * | important point. Probably too broad to frame as a flashcard, but should be noted down in the Summary section of the writeup |

| … | this is complicated - think about it some more during the writeup |

| lol | nice quote - copy it down during the writeup and add to the universal "nice quotes" list. (I started using this symbol just for funny quotes, but then it evolved to signify all types of nice quotes. This has lead to a stack of evidence that will no doubt one day come to haunt me in court - "With his heart falling into a black abyss, Thomas pulled the trigger" LOL) |

I also have a few symbols I use as shorthand for common notes:

| orly | I don’t believe you |

|---|---|

| R | section that is particularly relevant if you’re planning on writing a review. Probably contains something very good or very stupid |

In addition, write your own longform sentences in the margins, with big arrows pointing at the section of the text they are referring to. Use them to:

- Rephrase or copy out verbatim important points

- “Poor EU countries pissed that they had to bailout richer Greece and fund their seniors’ lavish pensions”

- Write down any additional thoughts or connections that come to mind

- “I guess that bad things will happen if you over-estimate the power of your risk management models, no matter how good those models are”

- Write down any questions you have that the author hasn’t answered. Put the question mark in a square (see below)

- “Why did small economies want to join the Euro?”

These handwritten notes force you to engage more with what you are reading and will form the basis of the Summary section of your writeup. Finally, at the end of each chapter, flip back through it and scribble down a quick outline of what was in it. Don’t stop a reading session at the end of a chapter without writing the summary - if you don’t do it straightaway then you never will.

Once you have finished the book and are armed with symbols, sentences, summaries and some understanding of what you have just read, you are ready to begin consolidating your new knowledge in the writeup.

2. The writeup

The best time to start (and ideally finish) a writeup is the same day, or at most the day after you finish a book and the knowledge is still fresh in your mind and ready for repetition. Starting a writeup is much harder work than just moving on to the next book on your list, so it’s important to keep up momentum.

Begin your writeup with a template. I use one with headings for:

- Reviews

- Summary

- Quotes

- Questions

- My thoughts

Start by reading reviews and making brief notes on them. Next, thumb through the book and sweep up all of the annotations that you left for yourself. The bulk of this should be a stream of consciousness summary (written in the “Summary” section), guided by the points in the book that you either put a big * next to or wrote out yourself in longhand in the margins. I distinguish between notes that are coming straight from the text and those that are my interpretation of it by adding an arrow (=>) before the latter. I use quotation marks to signify a point that the author makes but that I don’t necessarilly agree with. You can add chapter headings and the occasional page number to help map from your notes back to the relevant section of the book if you ever need to.

“These affluent Democrats do not give a damn about inequality except as an election year slogan” (p92)

=> This is SUCH a strong statement - how does he know?

As well as writing a Summary, you should:

- Add each nice quote (marked in the book with a lol) to the “Quotes” section

- Add each point to remember (marked with a Q) as a flashcard in Anki

- Add each point to research (marked with a ?) to the “Questions” section

After this, go back through your list of “Questions”, researching each one and making more flash cards. If you feel so moved then you can finish with a stream of consciousness of your overall reaction to the book in the “Thoughts” section. I also like to copy the list of “Quotes” into a master list of nice snippets, with a note of where they came from.

Everyone should keep a pile of aphorisms lying around - you never know when you’ll need one.

- Robert Heaton

Conclusion

If you follow this process and keep up with reviewing your flashcards, you will remember more of what you read. You can also find other ways to increase your reps. Find people to yammer at about what you are learning. If my experience if anything to go by then my wife would be very happy to talk to you, especially if you remember her father’s birthday. If you can think of something coherent to say about a book, write a review. If a book was good enough then read it again a year later (I have not done this very often).

On the other hand, if a book was boring or shallow then you don’t have to spend any more time on it. If you decide that you don’t care about remembering any of what you just read, don’t bother writing it up and just move onto a better book. If you want to read a book as “general background” and not spend too much time on it, then whilst I think you’re probably deceiving yourself somehow, that’s still totally fine with me. I listen to several hours of podcasts a week and feel good if I remember the name of one senator and the rough state of the Malaysian economy according to some woman whose name I don’t recall. But I am fine with this - I like the presenters’ voices and maybe there is such a thing as “general background” after all.

I do think that the most important thing is being honest with yourself. If you’re reading purely for fun, go and have as much fun as you possibly can and never look back. But if you’re reading for knowledge, be aware that this is quite a different thing.