How Tinder keeps your exact location (a bit) private

09 Jul 2018

You and your good buddy, Steve Steveington, are the co-founders and co-CEOs of an online tracking company. You started the company less than a year ago in order to commercialize a WhatsApp metadata leak that you discovered. You could both sorely use some co-leadership training, but you’ve still managed to grow the company into a powerful and precariously employed team of 65 assorted interns, work experience kids, Task Rabbits and unpaid trial workers. You recently moved into an exquisite new office in the 19th Century Literature section of the San Francisco Public Library, and your reputation in the online marketing sector is flourishing.

But beneath this glossy and disreputable exterior lies turmoil. You suspect that Steve Steveington, your good buddy, co-founder and co-CEO, is plotting against you. He keeps darting out of the library at odd times, for hours on end. When you ask him where he’s going he makes a weird grimace that he probably thinks is a malevolent smile and tells you not to worry. You’ve ordered the librarians to tail him several times, but they are all terrible at fieldcraft.

You’ve lived in Silicon Valley for long enough to know the kind of cutthroat villainy that goes on when large sums of money and user data are at stake. Steve Steveington is probably trying to convince your investors to squeeze you out. You think that Peter Thiel will back you up, but aren’t so sure about Aunt Martha. You have to find out where Steve is going.

Fortunately, the Stevester is an avid Tinder user. The Tinder app tracks its users’ locations in order to tell potential matches how far away they are from each other. This enables users to make rational decisions about whether it’s really worth traveling 8 miles to see a 6, 6.5 tops, when they’ve also got a tub of ice cream in the fridge and work the next morning. And this means that Tinder knows exactly where Steve is going. And if you can find the right exploit, soon you will too.

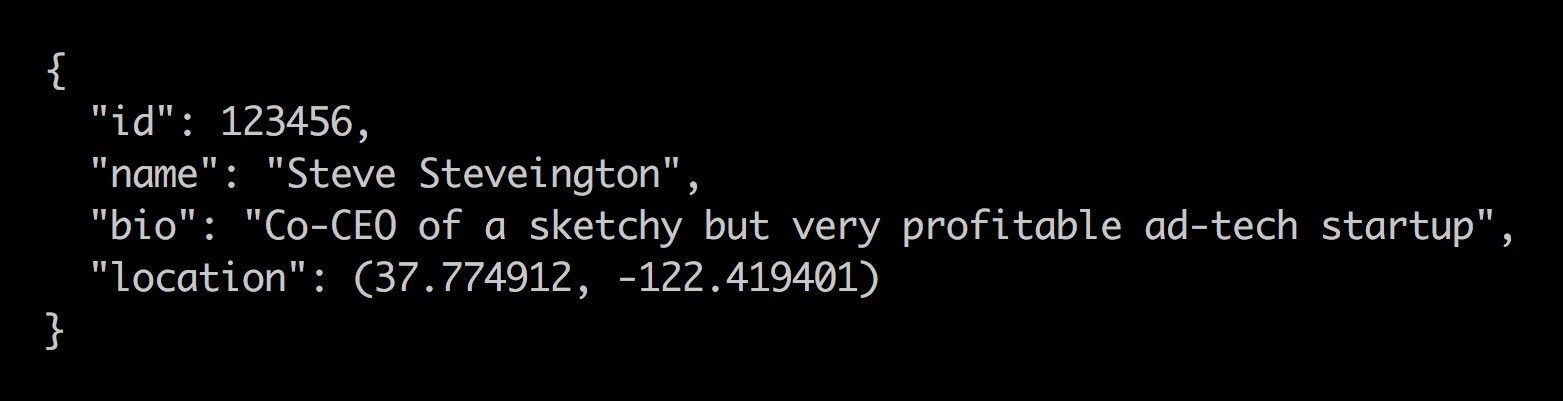

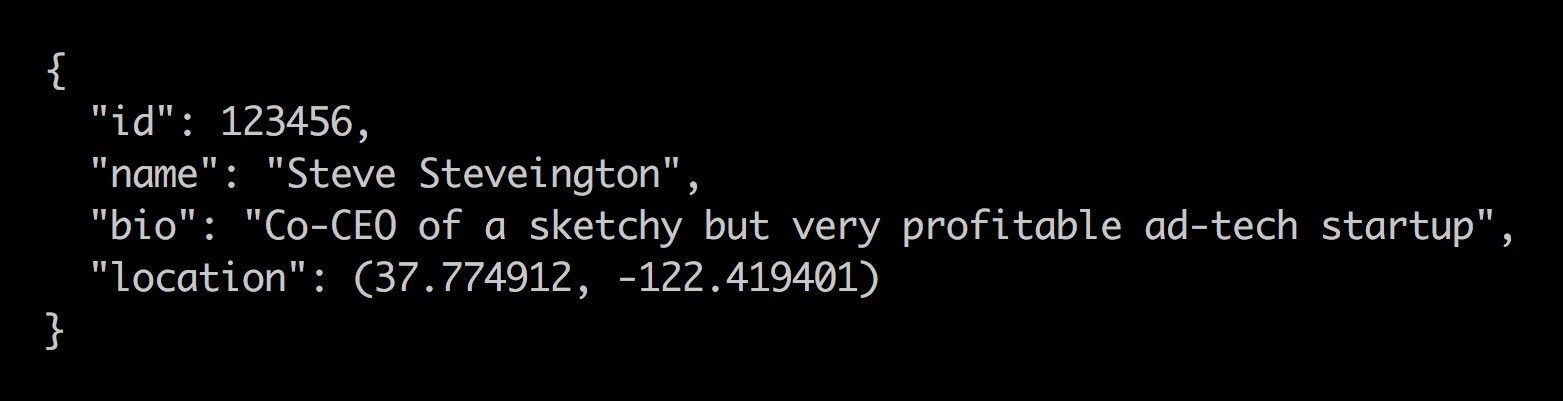

You scour the online literature to find inspiration from Tinder’s past location privacy vulnerabilities. There are several to choose from. In 2013, it was discovered that the Tinder servers sent potential matches’ exact co-ordinates to the Tinder phone app. The app internally used these co-ordinates to calculate distances between users, and did not display them in the interface. However, an attacker could easily intercept their own Tinder network traffic, inspect the raw data, and reveal a target’s exact location. When the issue was discovered, Tinder denied the possibility that it was either avoidable or bad.

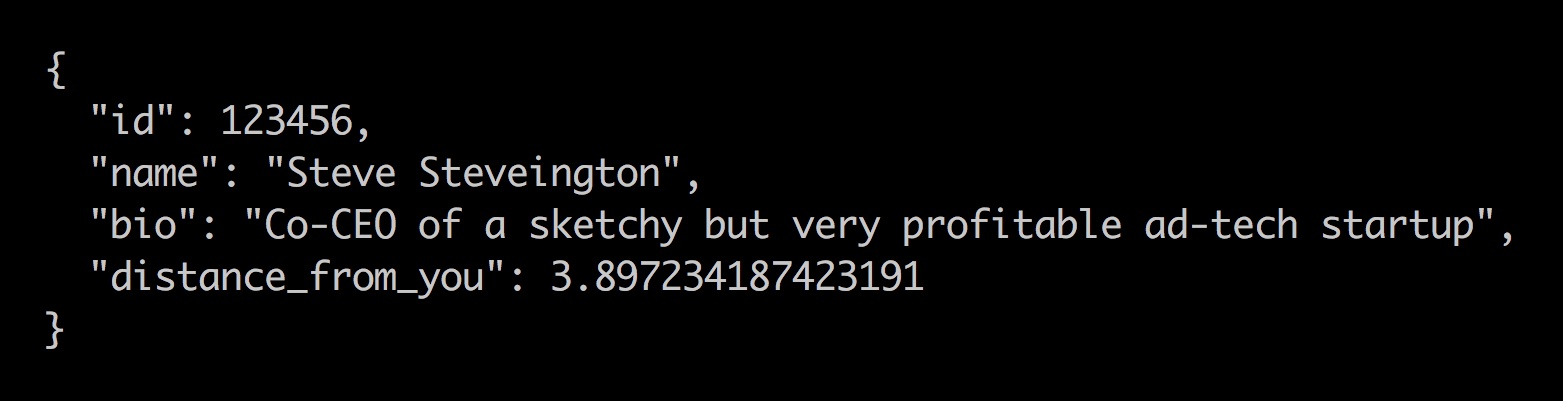

Tinder attempted to quietly fix this vulnerability by calculating distances on their servers instead of in their app. Now the network messages sent from server to app contained only these pre-calculated distances, with no actual locations. However, Tinder carelessly sent these distances as exact, unrounded numbers with a robust 15 decimal places of precision.

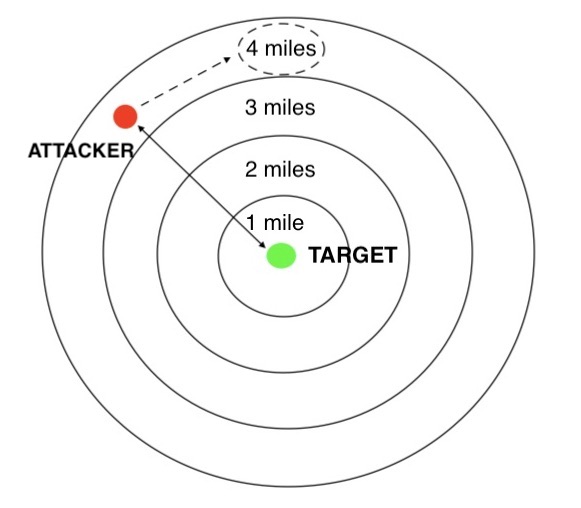

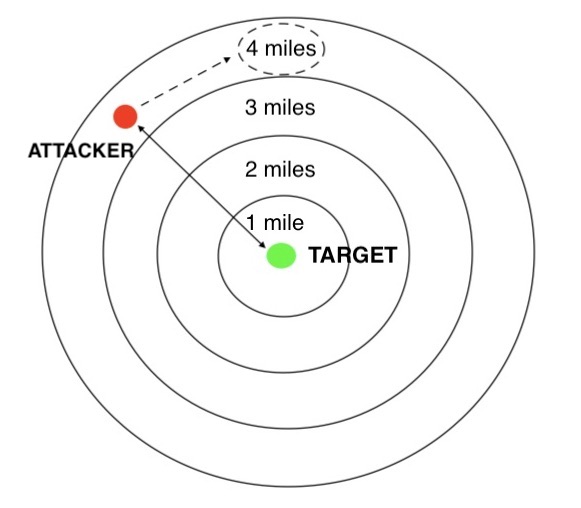

This new oversight allowed sneaky researchers to once again pinpoint a target’s exact location using a different, trilateration exploit. The researchers sent 3 spoofed location updates to Tinder to jump themselves around the city. At each new location they asked Tinder how far away their target was. Finally they drew 3 circles on a map, with centers equal to the spoofed locations and radii equal to the distances that they got back from Tinder. The point at which these circles intersected was their target’s location, to a reported accuracy of 30 meters.

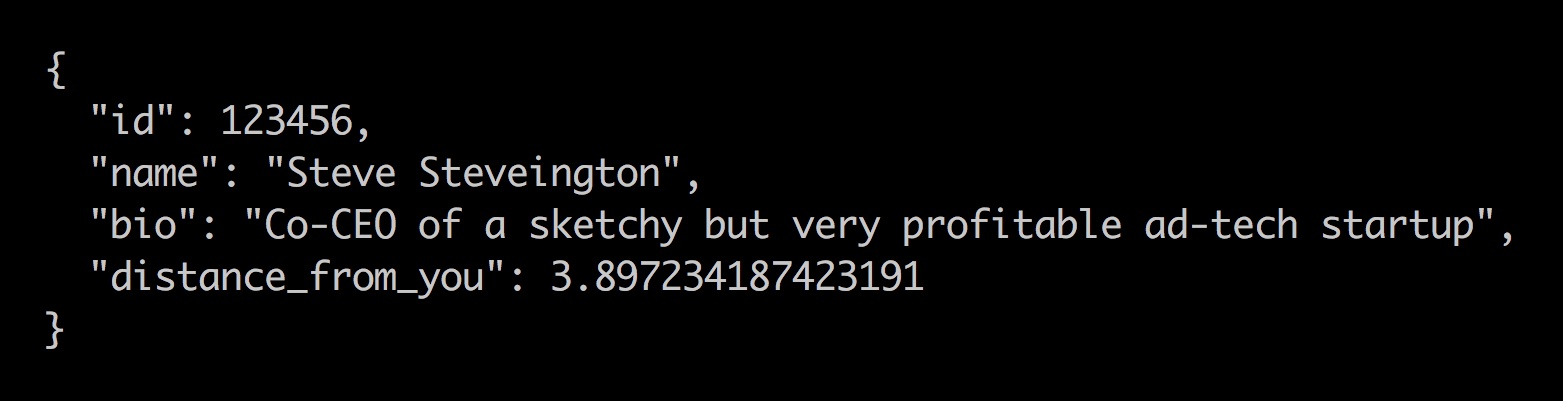

Tinder’s security team sighed, wished that people would stop asking them to do work all the time, and quietly fixed the vulnerability for real. Tinder now only ever sends your phone distances that are pre-rounded, in miles, with zero decimal places of precision. It’s still possible to use the above trilateration procedure to locate a target to within a mile or so. But in the densely populated city of San Francisco, this won’t tell you anything useful about where Steve Steveington is committing his dastardly subterfuge.

On Friday afternoon, Steve Steveington and his weird grimace sneak out once again to commit various deeds in undisclosed locations. You have to find out where he’s going before it’s too late. You barricade yourself in your private office, in the library reading room on the 4th floor. After fifteen minutes of deep breathing and even deeper thought, you hatch the beginnings of a plan to resuscitate the Tinder trilateration exploit and work out where the Stevenator is going.

Suppose that the Tinder now calculates exact distances on its servers, rounds them to the nearest integer, and then sends these rounded numbers to your phone. You could start a new attack in the same way as the trilateration researchers. You could spoof a Tinder location update and ask Tinder how far away your target is. Tinder might say “8 miles”, which on its own is of little use to you. But you could then start shuffling north, pixel-by-pixel, with each step asking Tinder again how far away your target is. “8 miles” it might say. “8 miles, 8 miles, 8 miles, 8 miles, 7 miles.” If your assumptions about Tinder’s approximation process are correct, then the point at which it flips from responding with “8 miles” to “7 miles” is the point at which your target is exactly 7.5 miles away. If you repeat this process 3 times and draw 3 circles, you’ve got trilateration again.

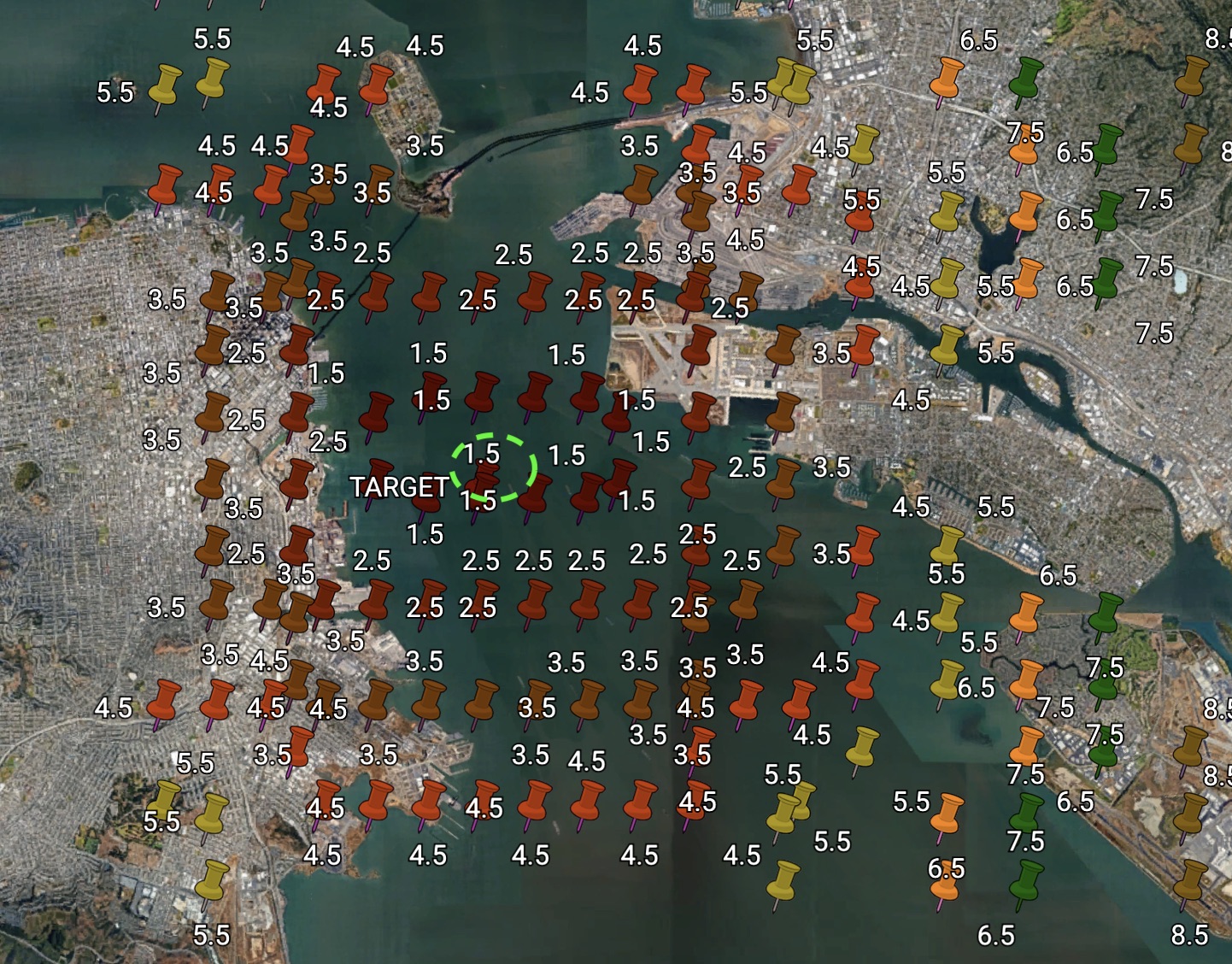

You leap into action. You borrow Wilson’s phone for testing whilst he’s in the bathroom because you know he uses Tinder and you can see his unlock code from the finger grease on his screen. You tell your unpaid trial period staff to hold your calls and to not say anything to Wilson. You rush off to the secluded and broody Young Adult Fiction section of your office. You open Tinder on both your and Wilson’s phones. You keep swiping until you match with each other, and then write a short Python script using pynder to spoof Tinder API calls. You place Wilson in the middle of the San Francisco Bay, and then try to reverse engineer his position by shuffling your account around and looking for the points where the distance between you flips from one rounded number to the next.

But something is wrong. Night falls, dinnertime passes, and you still haven’t re-located Wilson. You can get close-ish, but no cigar-ish. The circles sometimes come tantalizingly close to intersecting, but are more often unable to reach any useful consensus about where Wilson is. You start to despair - Steve Steveington could right this second be signing a new deal with Peter Thiel and Aunt Martha. He could have already updated your company LinkedIn page to make you an “Advisor” or an “Associate” or “vice-CEO”. The library closes, and you relocate to the supply closet. Wilson keeps calling his phone, but your unpaid trial period staff never rat you out. You briefly contemplate giving them jobs.

Frustrated, you take a step back. You bump your head on a low shelf. After extricating yourself from an avalanche of cleaning products, you contemplate the possibility that your assumptions might be wrong. Maybe Tinder is doing something more elaborate than calculating exact distances and rounding then. You grab a snack from the library employee fridge to help you think. You stop drawing circles and you start shuffling along lines that rake across Wilson’s true location, dropping a single pin whenever your distance from him changes.

Shortly after 1am, everything becomes clear.

Tinder is now so committed to privacy that it has burst the surly bonds of conventional geometry. It has cast aside Euclid. It has no need for the Haversine Formula. Instead, when calculating distances between matches, Tinder introduces 2 new innovations.

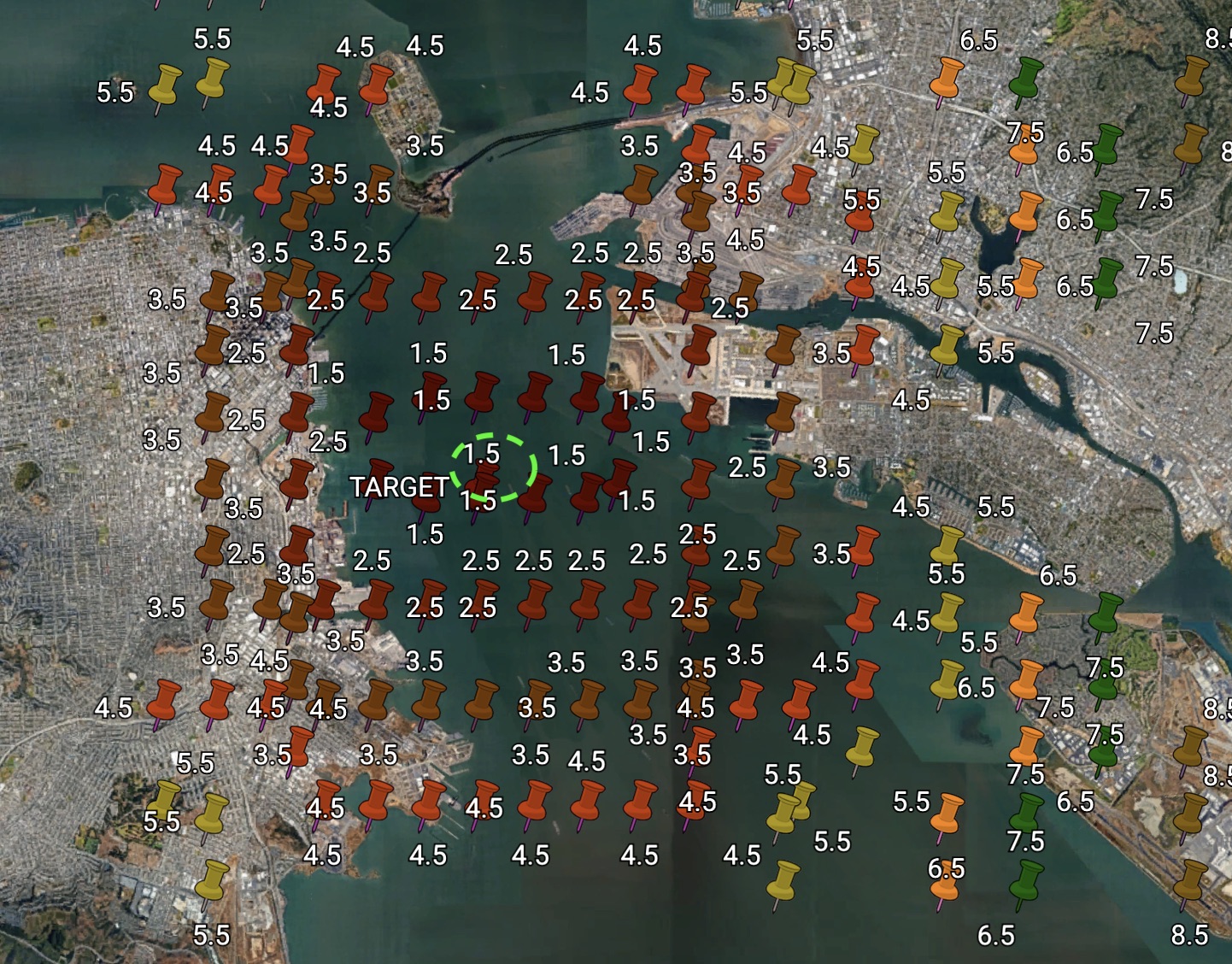

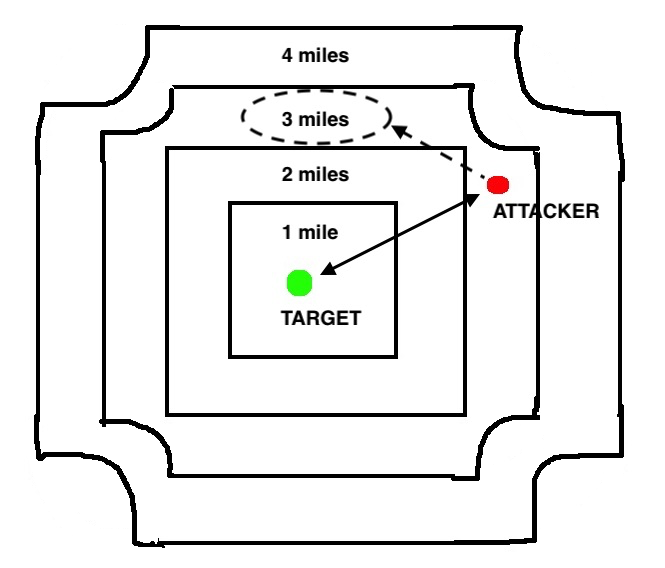

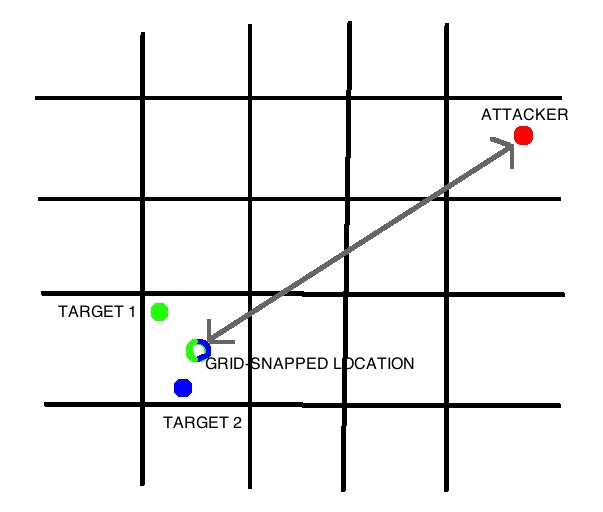

First and most important, it divides the city up into grid squares, very roughly 1 mile by 1 mile in size. When calculating the distance between an attacker and a target, it snaps the location of the target to the center of their current grid square. It then calculates and returns the approximate distance between the attacker and this snapped location.

Second, it calculates distances using what appears to be an entirely custom formula. To calculate the distance between an attacker and a target, it takes a map of rough, pre-determined distances, and overlays it on the centre of the target’s grid square. It looks up the attacker’s position in the overlay, and returns the corresponding distance. For normal, Euclidean distance calculations, this overlay would be a set of concentric circles.

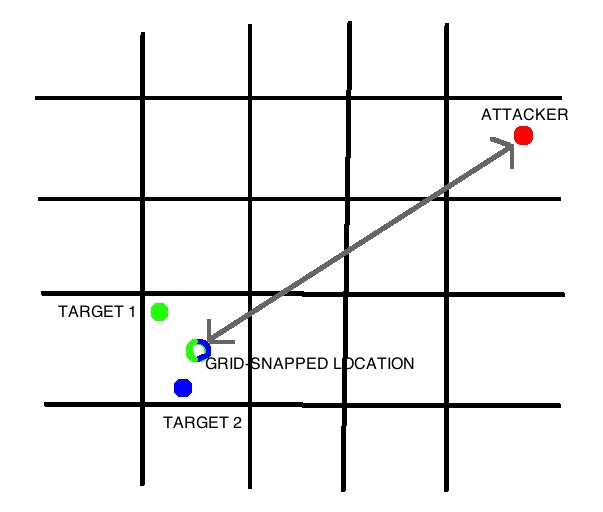

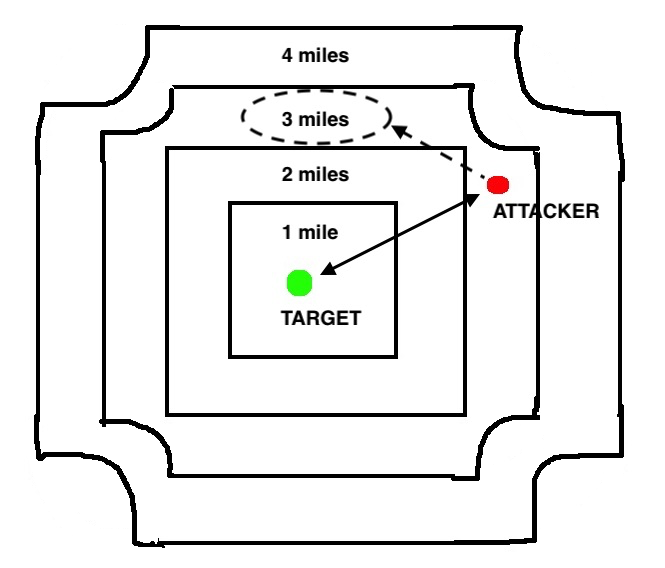

However, Tinder appears to use an overlay of concentric squares that start to develop some strange rounding on their corners as they get further away from the target.

Amongst other things, this means that Tinder often returns distances that are a little bit wrong. You suspect that the corner-rounding is to prevent distances between users who are due North-East of each other from becoming too wrong.

Grid-snapping is the key innovation in Tinder’s approach. It means that Tinder will always return the same distance if a target is located anywhere within a given grid square. Your shuffling trilateration exploit will not work, and indeed if Tinder has implemented grid-snapping correctly, no purely distance-based exploit can ever work. There is no way to find a target’s location with any more precision than knowing that they are somewhere in one of Tinder’s (roughly) 1 mile by 1 mile grid squares. Even this coarse-grained snooping should give Tinder users pause for thought. But it actually feels like about as much privacy as you can reasonably expect from an app whose main feature is that it tells strangers approximately where you are.

You aren’t actually sure why Tinder uses its odd, rounded square overlay. As long as user locations are snapped to a grid, Tinder could continue to use the normal Euclidean distance with no loss of privacy. Perhaps it’s simply that the new metric is faster to calculate, and despite what Gordon Moore promised us, computers aren’t free yet. Nonetheless, this all adds up to Tinder being secure - in this very specific respect - and you being screwed.

The library is pitch black apart from the green glow of the photocopier. You sadly but diligently clean up after yourself. You tidy the supply closet and toss Wilson’s phone into the library’s industrial shredder. You leave by the front entrance, steal a poorly-secured bike, and sadly roll home.

The next morning Steve Steveington presents you with one of the two matching “Co-CEO” mugs he has been working on at his secret daytime pottery classes. It is absolutely hideous. You would much rather he had given you one of two matching ten dollar bills and stayed in the office. His work is slow and bad at the best of times, and you’ve had to cover a lot of his meetings and tell a lot of lies it would usually be his job to tell. But at least he hasn’t stolen your company. You pour Wilson’s Starbucks into the grotesque cup and cheers your good buddy.

As you fall asleep that night you wonder what happens to Tinder’s co-ordinate grid at the North Pole…

The code that you used in this post is all on Github. Please do let yourself know if you have any questions or find any mistakes.

You and your good buddy, Steve Steveington, are the co-founders and co-CEOs of an online tracking company. You started the company less than a year ago in order to commercialize a WhatsApp metadata leak that you discovered. You could both sorely use some co-leadership training, but you’ve still managed to grow the company into a powerful and precariously employed team of 65 assorted interns, work experience kids, Task Rabbits and unpaid trial workers. You recently moved into an exquisite new office in the 19th Century Literature section of the San Francisco Public Library, and your reputation in the online marketing sector is flourishing.

But beneath this glossy and disreputable exterior lies turmoil. You suspect that Steve Steveington, your good buddy, co-founder and co-CEO, is plotting against you. He keeps darting out of the library at odd times, for hours on end. When you ask him where he’s going he makes a weird grimace that he probably thinks is a malevolent smile and tells you not to worry. You’ve ordered the librarians to tail him several times, but they are all terrible at fieldcraft.

You’ve lived in Silicon Valley for long enough to know the kind of cutthroat villainy that goes on when large sums of money and user data are at stake. Steve Steveington is probably trying to convince your investors to squeeze you out. You think that Peter Thiel will back you up, but aren’t so sure about Aunt Martha. You have to find out where Steve is going.

Fortunately, the Stevester is an avid Tinder user. The Tinder app tracks its users’ locations in order to tell potential matches how far away they are from each other. This enables users to make rational decisions about whether it’s really worth traveling 8 miles to see a 6, 6.5 tops, when they’ve also got a tub of ice cream in the fridge and work the next morning. And this means that Tinder knows exactly where Steve is going. And if you can find the right exploit, soon you will too.

You scour the online literature to find inspiration from Tinder’s past location privacy vulnerabilities. There are several to choose from. In 2013, it was discovered that the Tinder servers sent potential matches’ exact co-ordinates to the Tinder phone app. The app internally used these co-ordinates to calculate distances between users, and did not display them in the interface. However, an attacker could easily intercept their own Tinder network traffic, inspect the raw data, and reveal a target’s exact location. When the issue was discovered, Tinder denied the possibility that it was either avoidable or bad.

Tinder attempted to quietly fix this vulnerability by calculating distances on their servers instead of in their app. Now the network messages sent from server to app contained only these pre-calculated distances, with no actual locations. However, Tinder carelessly sent these distances as exact, unrounded numbers with a robust 15 decimal places of precision.

This new oversight allowed sneaky researchers to once again pinpoint a target’s exact location using a different, trilateration exploit. The researchers sent 3 spoofed location updates to Tinder to jump themselves around the city. At each new location they asked Tinder how far away their target was. Finally they drew 3 circles on a map, with centers equal to the spoofed locations and radii equal to the distances that they got back from Tinder. The point at which these circles intersected was their target’s location, to a reported accuracy of 30 meters.

Tinder’s security team sighed, wished that people would stop asking them to do work all the time, and quietly fixed the vulnerability for real. Tinder now only ever sends your phone distances that are pre-rounded, in miles, with zero decimal places of precision. It’s still possible to use the above trilateration procedure to locate a target to within a mile or so. But in the densely populated city of San Francisco, this won’t tell you anything useful about where Steve Steveington is committing his dastardly subterfuge.

On Friday afternoon, Steve Steveington and his weird grimace sneak out once again to commit various deeds in undisclosed locations. You have to find out where he’s going before it’s too late. You barricade yourself in your private office, in the library reading room on the 4th floor. After fifteen minutes of deep breathing and even deeper thought, you hatch the beginnings of a plan to resuscitate the Tinder trilateration exploit and work out where the Stevenator is going.

Suppose that the Tinder now calculates exact distances on its servers, rounds them to the nearest integer, and then sends these rounded numbers to your phone. You could start a new attack in the same way as the trilateration researchers. You could spoof a Tinder location update and ask Tinder how far away your target is. Tinder might say “8 miles”, which on its own is of little use to you. But you could then start shuffling north, pixel-by-pixel, with each step asking Tinder again how far away your target is. “8 miles” it might say. “8 miles, 8 miles, 8 miles, 8 miles, 7 miles.” If your assumptions about Tinder’s approximation process are correct, then the point at which it flips from responding with “8 miles” to “7 miles” is the point at which your target is exactly 7.5 miles away. If you repeat this process 3 times and draw 3 circles, you’ve got trilateration again.

You leap into action. You borrow Wilson’s phone for testing whilst he’s in the bathroom because you know he uses Tinder and you can see his unlock code from the finger grease on his screen. You tell your unpaid trial period staff to hold your calls and to not say anything to Wilson. You rush off to the secluded and broody Young Adult Fiction section of your office. You open Tinder on both your and Wilson’s phones. You keep swiping until you match with each other, and then write a short Python script using pynder to spoof Tinder API calls. You place Wilson in the middle of the San Francisco Bay, and then try to reverse engineer his position by shuffling your account around and looking for the points where the distance between you flips from one rounded number to the next.

But something is wrong. Night falls, dinnertime passes, and you still haven’t re-located Wilson. You can get close-ish, but no cigar-ish. The circles sometimes come tantalizingly close to intersecting, but are more often unable to reach any useful consensus about where Wilson is. You start to despair - Steve Steveington could right this second be signing a new deal with Peter Thiel and Aunt Martha. He could have already updated your company LinkedIn page to make you an “Advisor” or an “Associate” or “vice-CEO”. The library closes, and you relocate to the supply closet. Wilson keeps calling his phone, but your unpaid trial period staff never rat you out. You briefly contemplate giving them jobs.

Frustrated, you take a step back. You bump your head on a low shelf. After extricating yourself from an avalanche of cleaning products, you contemplate the possibility that your assumptions might be wrong. Maybe Tinder is doing something more elaborate than calculating exact distances and rounding then. You grab a snack from the library employee fridge to help you think. You stop drawing circles and you start shuffling along lines that rake across Wilson’s true location, dropping a single pin whenever your distance from him changes.

Shortly after 1am, everything becomes clear.

Tinder is now so committed to privacy that it has burst the surly bonds of conventional geometry. It has cast aside Euclid. It has no need for the Haversine Formula. Instead, when calculating distances between matches, Tinder introduces 2 new innovations.

First and most important, it divides the city up into grid squares, very roughly 1 mile by 1 mile in size. When calculating the distance between an attacker and a target, it snaps the location of the target to the center of their current grid square. It then calculates and returns the approximate distance between the attacker and this snapped location.

Second, it calculates distances using what appears to be an entirely custom formula. To calculate the distance between an attacker and a target, it takes a map of rough, pre-determined distances, and overlays it on the centre of the target’s grid square. It looks up the attacker’s position in the overlay, and returns the corresponding distance. For normal, Euclidean distance calculations, this overlay would be a set of concentric circles.

However, Tinder appears to use an overlay of concentric squares that start to develop some strange rounding on their corners as they get further away from the target.

Amongst other things, this means that Tinder often returns distances that are a little bit wrong. You suspect that the corner-rounding is to prevent distances between users who are due North-East of each other from becoming too wrong.

Grid-snapping is the key innovation in Tinder’s approach. It means that Tinder will always return the same distance if a target is located anywhere within a given grid square. Your shuffling trilateration exploit will not work, and indeed if Tinder has implemented grid-snapping correctly, no purely distance-based exploit can ever work. There is no way to find a target’s location with any more precision than knowing that they are somewhere in one of Tinder’s (roughly) 1 mile by 1 mile grid squares. Even this coarse-grained snooping should give Tinder users pause for thought. But it actually feels like about as much privacy as you can reasonably expect from an app whose main feature is that it tells strangers approximately where you are.

You aren’t actually sure why Tinder uses its odd, rounded square overlay. As long as user locations are snapped to a grid, Tinder could continue to use the normal Euclidean distance with no loss of privacy. Perhaps it’s simply that the new metric is faster to calculate, and despite what Gordon Moore promised us, computers aren’t free yet. Nonetheless, this all adds up to Tinder being secure - in this very specific respect - and you being screwed.

The library is pitch black apart from the green glow of the photocopier. You sadly but diligently clean up after yourself. You tidy the supply closet and toss Wilson’s phone into the library’s industrial shredder. You leave by the front entrance, steal a poorly-secured bike, and sadly roll home.

The next morning Steve Steveington presents you with one of the two matching “Co-CEO” mugs he has been working on at his secret daytime pottery classes. It is absolutely hideous. You would much rather he had given you one of two matching ten dollar bills and stayed in the office. His work is slow and bad at the best of times, and you’ve had to cover a lot of his meetings and tell a lot of lies it would usually be his job to tell. But at least he hasn’t stolen your company. You pour Wilson’s Starbucks into the grotesque cup and cheers your good buddy.

As you fall asleep that night you wonder what happens to Tinder’s co-ordinate grid at the North Pole…

The code that you used in this post is all on Github. Please do let yourself know if you have any questions or find any mistakes.