Making peace with Simpson's Paradox

24 Feb 2019

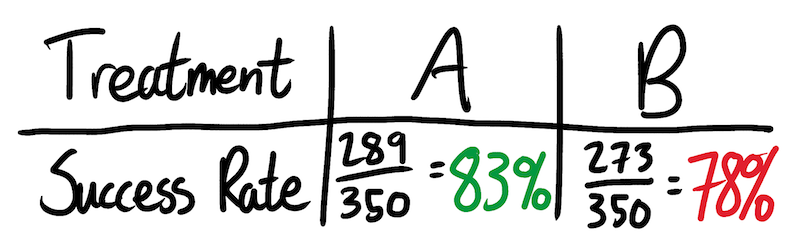

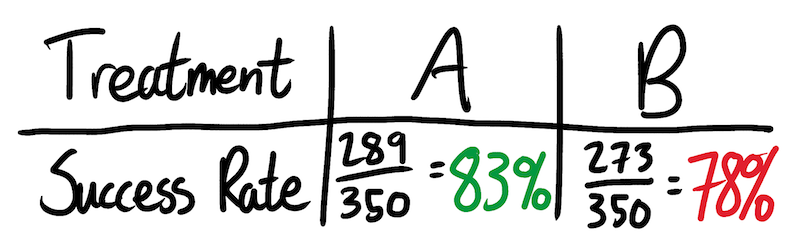

Two years ago you were diagnosed with a kidney stone. You went to see your town’s most famous kidney doctor, Dr. Alpha. She explained that you had two options - Treatment A or Treatment B. She recommended Treatment A, and justified her choice with a detailed data table.

Since you are respectful to the point of deference to people in white coats wielding numbers, you agreed immediately. As the anesthetist put you under, you began to wonder “I hope those stats were properly controlled for confounding…”

Despite Dr. Alpha’s favorable numbers, the operation was a failure. The stone eventually passed out of your body naturally, but you were still pretty peeved about the whole experience.

And that wasn’t the end of the story. Despite sticking rigidly with a good 40% of Dr. Alpha’s advice for preventing future kidney stones, a year later you were diagnosed with a second stone. Unimpressed with Dr. Alpha, this time you went to see Dr. Beta. He explained that you still had the same two options - Treatment A or Treatment B. However, whereas Dr.Alpha had recommended Treatment A, Dr. Beta recommended Treatment B. He justified his choice with his own data table.

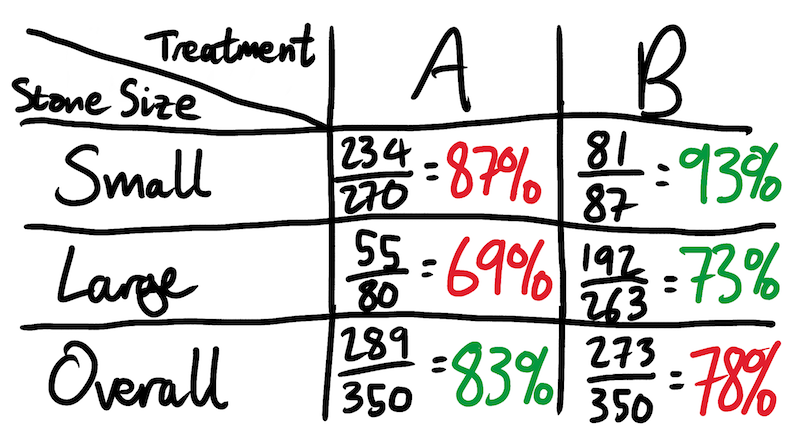

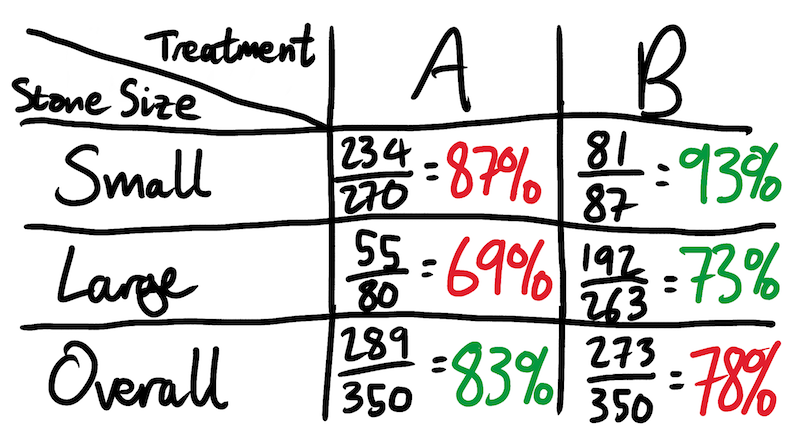

Dr. Beta reasoned that even though Treatment A’s overall success rate was indeed higher, Treatment B’s individual success rates were higher for both small and large kidney stones. Since by definition you must have either a small or a large kidney stone, and the success rates for both sizes are higher with Treatment B, you should go with Treatment B.

You felt quite strongly that something impossible was happening to you. How could Treatment B have higher individual success rates for both large and small kidney stones, yet have a lower success rate overall? Didn’t that mean that if you didn’t know whether you had a small or large stone then you should choose Treatment A, but as soon as you were told what size stone you had you should choose Treatment B, regardless of the size of the stone? But you didn’t have a pen and paper handy, and Dr. Beta was getting impatient. Bamboozled and surrounded by white coats and contradictory numbers, you opted for the path of least resistance and agreed with the white coat in front of you.

Treatment B was a complete success. You were happy, but haunted by the impossible numbers that you had seen. You resolved to get to the bottom of the mater. You searched the internet for cut-price algebra assistance and found Steve Steveington, Statistician to the Stars, 3.8 miles from you, average 1.5/5 from 4 ratings. You hoped that he could help you understand whether you were crazy or whether maths was. Even if he couldn’t, he really was very cheap, especially for someone whose Yelp profile claimed that he regularly ran ridge regressions for Rhianna.

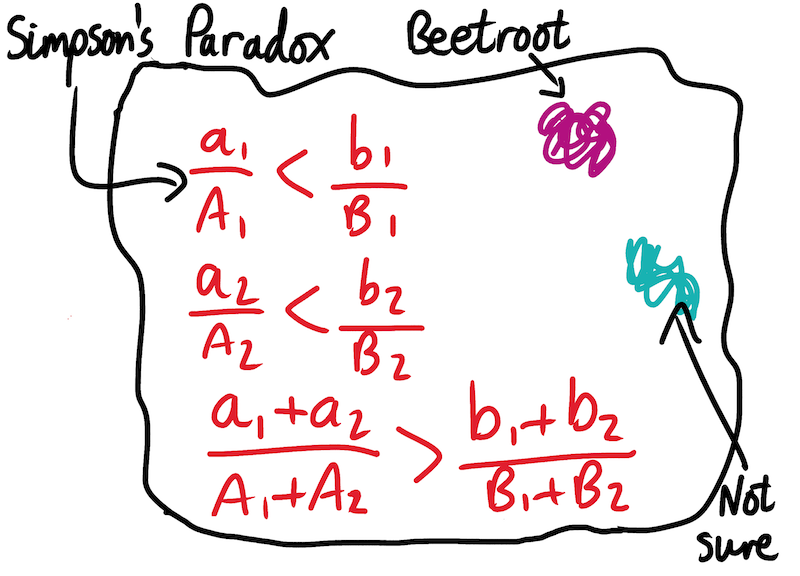

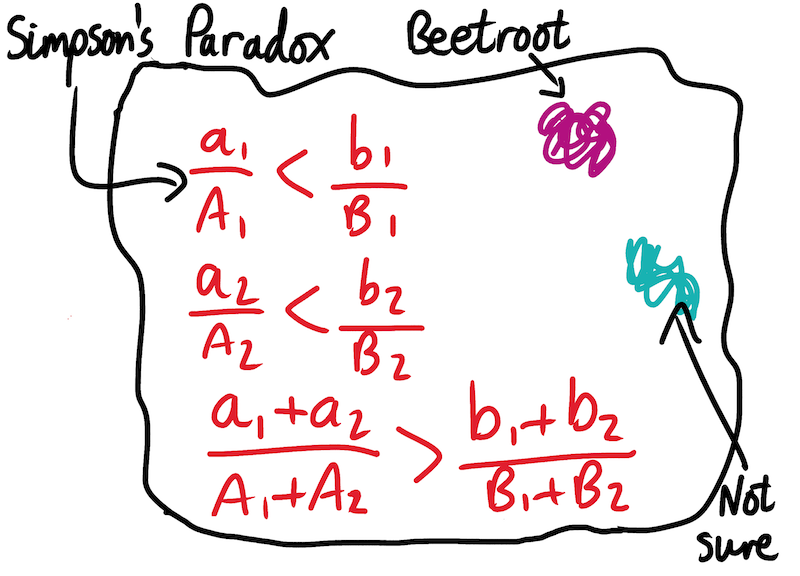

“This is just Simpson’s Paradox,” Steveington says, brusquely. “The maths behind it is insanely boring. It’s just a mathematical fact that all of the following inequalities can be true simultaneously.” He scrawls some barely legible equations on a food-stained napkin:

“The only thing that I find interesting about Simpson’s Paradox is why people are always so surprised by it in the first place. It really shows how unintuitive and unhelpful statistics can be without a story to explain them. Take your kidney stone situation. I can tell you for certain that Dr. Beta was right, and Treatment B is simply the better treatment in all situations. The reason I am so confident about this is because I know the narrative behind the numbers.

“I happen to know that Treatment A is cheaper than Treatment B. This means that doctors tend to recommend Treatment A for small kidney stones. Even though it’s a bit worse than Treatment B, Treatment A will still perform pretty well for a lot less money. Doctors therefore typically reserve Treatment B for only the larger, trickier stones.

“This means that Treatment A gets to rack up a large number of easy wins on small kidney stones, whereas Treatment B performs admirably but relatively worse on the larger, more difficult ones. When you come to calculate overall rates, Treatment A’s success rate is dominated by all the easy stones it got to work on. Treatment B’s success rate is higher on both small and large stones, but since it is mostly used on larger, more difficult stones, its overall rate looks superficially worse.

“So as a patient your ideal outcome is that your doctor says ‘I think you should do Treatment A’ - which suggests they think you are an easy case - but then you threaten to sue them unless they give you Treatment B, so you get the best treatment.”

“The apparent paradox occurs when people try to directly combine numbers that shouldn’t be combined, or that at least should only be combined with great care and control variables. Such mistakes can be partially prevented by presentation. Your doctors both said to you ‘you can choose either Treatment A or Treatment B’. Suppose they had instead said ‘you can choose either Treatment-Mostly-Used-For-Small-Stones-Because-Its-Cheap or Treatment-Mostly-Used-For-Large-Stones-Because-Its-Expensive,’ and had presented you with each of their combined success rates for small and large stones. You’d probably have demanded to know which type of stone you were suffering from before you made your choice. As soon as a property is given salience somehow, you become wise to the possibility that it might be a confounding variable. You start looking for how it might have been stomping around in your statistics and fiddling with your filing system.

“Maybe even this example would be too subtle. What if your doctor said ‘I’ve reviewed your test results, and I’ve narrowed it down to two options. Either you need to have a kidney stone out, or you need a haircut. You can either choose Surgeon A or Surgeon B. Here is a combined percentage for the success rates of their operations and their haircuts.’ I think this time you really would ask for these two statistics to be split out. It’s immediately obvious that you shouldn’t be choosing your medical treatment based on your surgeon’s barbershop prowess.

“But there’s no real difference between the kidney stone size and the haircut scenarios, other than an increase in absurdity. In the first scenario the confounding variable is whether you need to get a small or a large kidney stone removed. In the second it’s whether you need to get a kidney stone removed or a short back and sides. The only thing that changed is the story and the labels.

“We can also dissolve other common examples of Simpson’s Paradox with nothing more than better framing. One often-quoted example is the fact that baseball player David Justice hit higher batting averages than baseball player Derek Jeter in both the 1995 and 1996 seasons, but Jeter hit the higher average overall. Without any extra color this sounds just as impossible as the kidney stones situations.

“So what if I told you that 1995 was a great year for batters overall, but David Justice was injured for most of the season? What if I made it even starker and told you that in 1995 the MLB decided to award two points for every hit, and David Justice was still injured for most of the season? You might start to think that maybe we should be careful when combining data from two different years. I haven’t changed the mathematics at all, but I’ve added enough extra color to make you question whether the naive comparisons that we’re making are really sensible and warranted.

“There are some quantities that our brains know instinctively shouldn’t be aggregated, with no need for any extra narrative. Another sports example - suppose that you and I are both training for the 100m and 400m sprints. I’m faster than you over both distances, but I mostly run the 400m, whereas you mostly run the 100m. If you wanted to “prove” that you were faster than me, you could calculate our average race times across both distances combined. Your average would be dominated by all your 100m times, whereas mine would be dominated by my impressive but obviously longer 400m times. You could draw a table just like the ones that we’ve seen already, and boast about your superior average speed.

“But no one would listen to you. Even though there’s once again no functional difference between this example and your kidney stones one, now the hoodwinkery is easy to spot. It’s obvious that you shouldn’t directly combine and compare 100m and 400m sprint times, and so our minds instinctively and immediately go looking for the statistical fiddle.

“There’s another formulation of Simpson’s Paradox that I’d love to talk about - but oh look our hour is up. Do you want to…?”

You pay him another goddamn seven dollars.

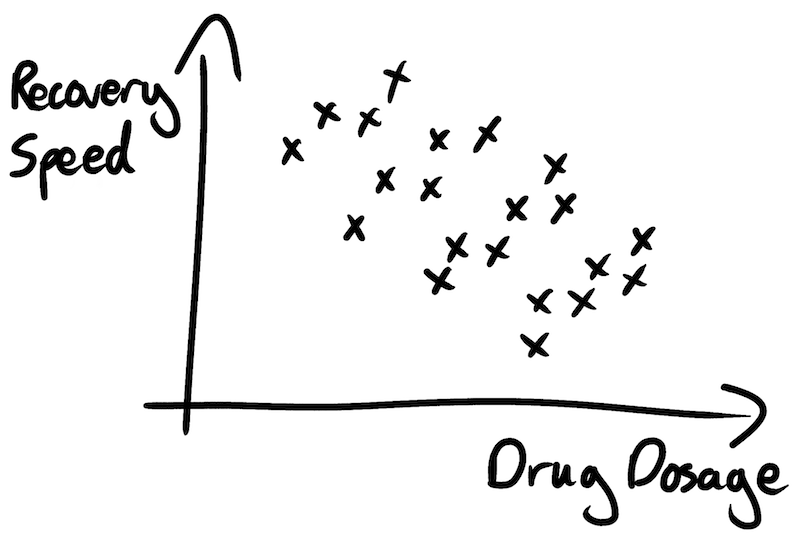

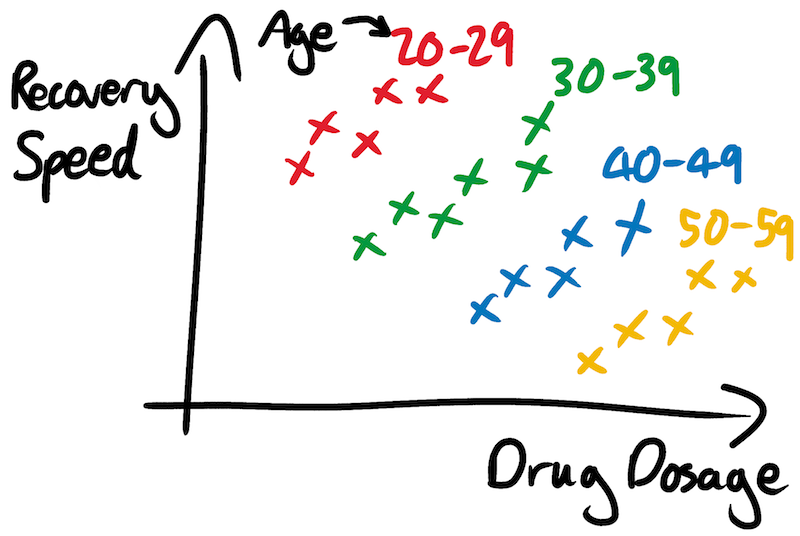

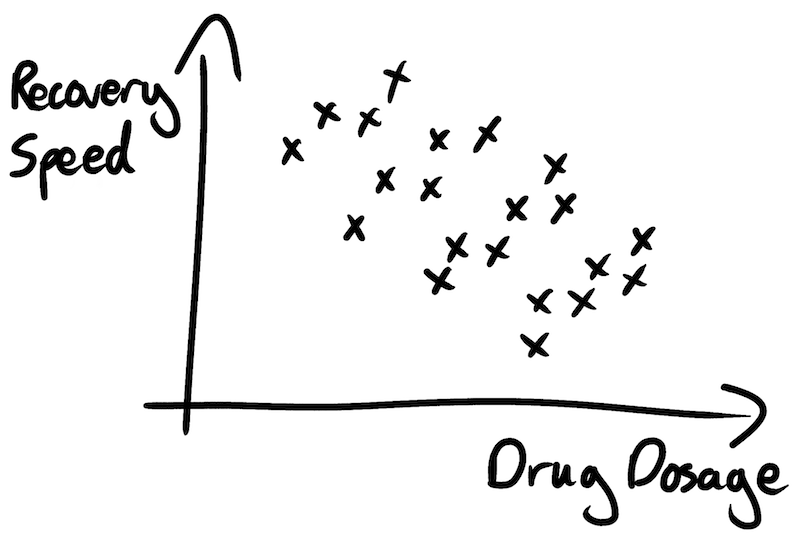

“Thank you kindly. Suppose you have an illness, and you’re trying to work out what level of drug dosage will help you recover the fastest. You find the following graph of drug dosage against recovery speed:”

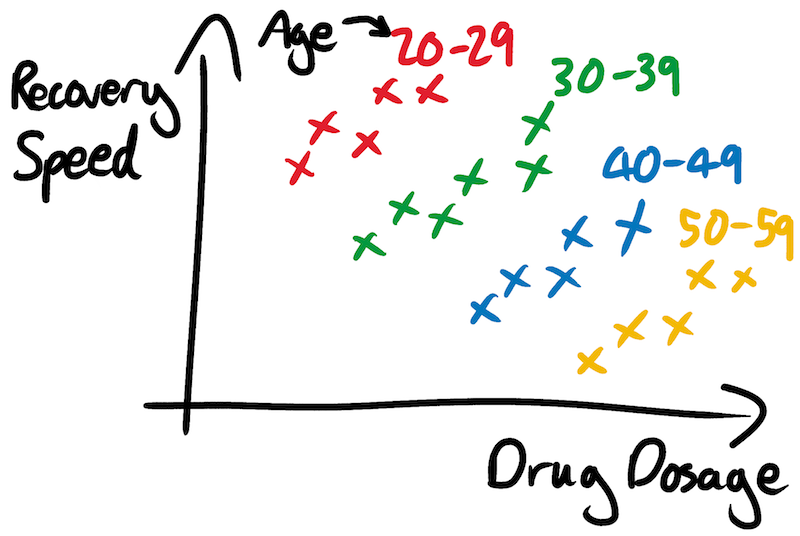

“The overall trend is clearly down. This implies that high drug dosages cause slow recoveries - right? But what if we group people by age?”

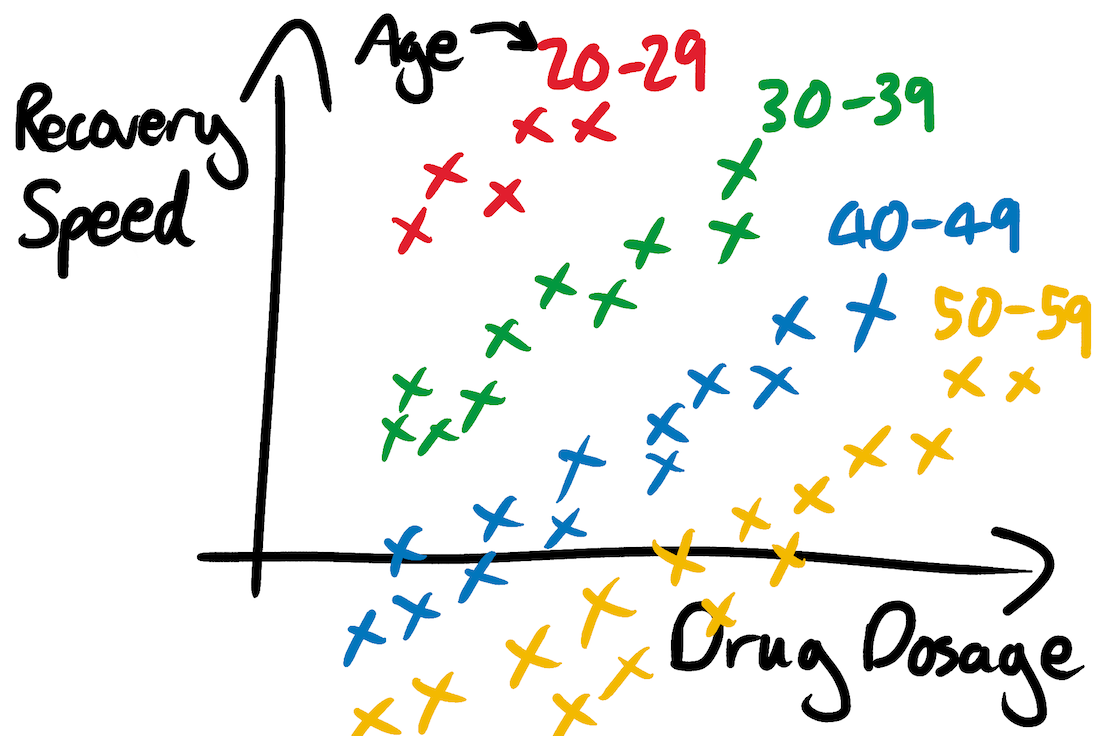

“If you’re 20 years old, you want more drugs. If you’re 30 years old, you want more drugs. If you’re 40 years old, you want more drugs. But if you don’t know how old you are, it seems like you want fewer drugs. It’s Simpson’s Paradox again, but wearing a slightly different hat.

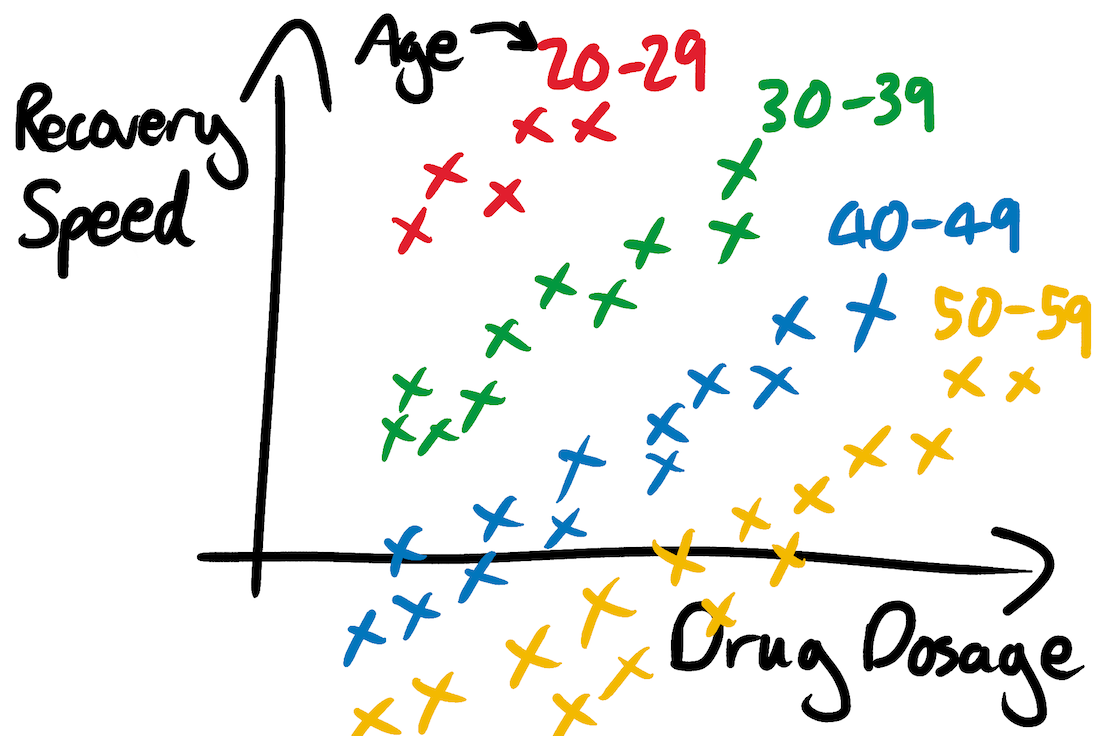

“This time the confounder is age. When you say ‘I want fewer drugs so that I recover faster’, what you really mean is ‘I want to be one of these little crosses up in the top-left.’ However, all of those dots in the top-left are 20 years old. If you’re 50 then the way to become one of those dots isn’t to take fewer drugs. It’s to become 20 years old again. There aren’t any dots for 50 year olds who got low doses because doctors know that 50 year olds need high doses in order to recover at all. The graph might become less paradoxical if doctors started experimenting more, but also much much more unethical:

“All this means that you don’t want to ask your doctor to give you a low dose. Instead, you want to be someone who your doctor thinks should have a low dose. Sadly, by the time you’ve been admitted to the ER, you’re all out of agency in that regard.”

You still have twenty-five minutes out of your second one hour statistical session left. You ask Steveington if you can get a $7 * 25/60 = $2.92 refund for the unused time. He says that he’s sorry but he’s unable to bill for fractions of an hour. You fill the time by asking him some questions about Natural Experiments that had been on your mind for a while.

A year later you get a third kidney stone. Sadly there is still no Treatment C, with a 100% success rate for all stones, no questions asked. But you are at least able to choose Treatment B confidently. As the anesthetist puts you under yet again, you feel as content as it is possible to be, given the circumstances.

Two years ago you were diagnosed with a kidney stone. You went to see your town’s most famous kidney doctor, Dr. Alpha. She explained that you had two options - Treatment A or Treatment B. She recommended Treatment A, and justified her choice with a detailed data table.

Since you are respectful to the point of deference to people in white coats wielding numbers, you agreed immediately. As the anesthetist put you under, you began to wonder “I hope those stats were properly controlled for confounding…”

Despite Dr. Alpha’s favorable numbers, the operation was a failure. The stone eventually passed out of your body naturally, but you were still pretty peeved about the whole experience.

And that wasn’t the end of the story. Despite sticking rigidly with a good 40% of Dr. Alpha’s advice for preventing future kidney stones, a year later you were diagnosed with a second stone. Unimpressed with Dr. Alpha, this time you went to see Dr. Beta. He explained that you still had the same two options - Treatment A or Treatment B. However, whereas Dr.Alpha had recommended Treatment A, Dr. Beta recommended Treatment B. He justified his choice with his own data table.

Dr. Beta reasoned that even though Treatment A’s overall success rate was indeed higher, Treatment B’s individual success rates were higher for both small and large kidney stones. Since by definition you must have either a small or a large kidney stone, and the success rates for both sizes are higher with Treatment B, you should go with Treatment B.

You felt quite strongly that something impossible was happening to you. How could Treatment B have higher individual success rates for both large and small kidney stones, yet have a lower success rate overall? Didn’t that mean that if you didn’t know whether you had a small or large stone then you should choose Treatment A, but as soon as you were told what size stone you had you should choose Treatment B, regardless of the size of the stone? But you didn’t have a pen and paper handy, and Dr. Beta was getting impatient. Bamboozled and surrounded by white coats and contradictory numbers, you opted for the path of least resistance and agreed with the white coat in front of you.

Treatment B was a complete success. You were happy, but haunted by the impossible numbers that you had seen. You resolved to get to the bottom of the mater. You searched the internet for cut-price algebra assistance and found Steve Steveington, Statistician to the Stars, 3.8 miles from you, average 1.5/5 from 4 ratings. You hoped that he could help you understand whether you were crazy or whether maths was. Even if he couldn’t, he really was very cheap, especially for someone whose Yelp profile claimed that he regularly ran ridge regressions for Rhianna.

“This is just Simpson’s Paradox,” Steveington says, brusquely. “The maths behind it is insanely boring. It’s just a mathematical fact that all of the following inequalities can be true simultaneously.” He scrawls some barely legible equations on a food-stained napkin:

“The only thing that I find interesting about Simpson’s Paradox is why people are always so surprised by it in the first place. It really shows how unintuitive and unhelpful statistics can be without a story to explain them. Take your kidney stone situation. I can tell you for certain that Dr. Beta was right, and Treatment B is simply the better treatment in all situations. The reason I am so confident about this is because I know the narrative behind the numbers.

“I happen to know that Treatment A is cheaper than Treatment B. This means that doctors tend to recommend Treatment A for small kidney stones. Even though it’s a bit worse than Treatment B, Treatment A will still perform pretty well for a lot less money. Doctors therefore typically reserve Treatment B for only the larger, trickier stones.

“This means that Treatment A gets to rack up a large number of easy wins on small kidney stones, whereas Treatment B performs admirably but relatively worse on the larger, more difficult ones. When you come to calculate overall rates, Treatment A’s success rate is dominated by all the easy stones it got to work on. Treatment B’s success rate is higher on both small and large stones, but since it is mostly used on larger, more difficult stones, its overall rate looks superficially worse.

“So as a patient your ideal outcome is that your doctor says ‘I think you should do Treatment A’ - which suggests they think you are an easy case - but then you threaten to sue them unless they give you Treatment B, so you get the best treatment.”

“The apparent paradox occurs when people try to directly combine numbers that shouldn’t be combined, or that at least should only be combined with great care and control variables. Such mistakes can be partially prevented by presentation. Your doctors both said to you ‘you can choose either Treatment A or Treatment B’. Suppose they had instead said ‘you can choose either Treatment-Mostly-Used-For-Small-Stones-Because-Its-Cheap or Treatment-Mostly-Used-For-Large-Stones-Because-Its-Expensive,’ and had presented you with each of their combined success rates for small and large stones. You’d probably have demanded to know which type of stone you were suffering from before you made your choice. As soon as a property is given salience somehow, you become wise to the possibility that it might be a confounding variable. You start looking for how it might have been stomping around in your statistics and fiddling with your filing system.

“Maybe even this example would be too subtle. What if your doctor said ‘I’ve reviewed your test results, and I’ve narrowed it down to two options. Either you need to have a kidney stone out, or you need a haircut. You can either choose Surgeon A or Surgeon B. Here is a combined percentage for the success rates of their operations and their haircuts.’ I think this time you really would ask for these two statistics to be split out. It’s immediately obvious that you shouldn’t be choosing your medical treatment based on your surgeon’s barbershop prowess.

“But there’s no real difference between the kidney stone size and the haircut scenarios, other than an increase in absurdity. In the first scenario the confounding variable is whether you need to get a small or a large kidney stone removed. In the second it’s whether you need to get a kidney stone removed or a short back and sides. The only thing that changed is the story and the labels.

“We can also dissolve other common examples of Simpson’s Paradox with nothing more than better framing. One often-quoted example is the fact that baseball player David Justice hit higher batting averages than baseball player Derek Jeter in both the 1995 and 1996 seasons, but Jeter hit the higher average overall. Without any extra color this sounds just as impossible as the kidney stones situations.

“So what if I told you that 1995 was a great year for batters overall, but David Justice was injured for most of the season? What if I made it even starker and told you that in 1995 the MLB decided to award two points for every hit, and David Justice was still injured for most of the season? You might start to think that maybe we should be careful when combining data from two different years. I haven’t changed the mathematics at all, but I’ve added enough extra color to make you question whether the naive comparisons that we’re making are really sensible and warranted.

“There are some quantities that our brains know instinctively shouldn’t be aggregated, with no need for any extra narrative. Another sports example - suppose that you and I are both training for the 100m and 400m sprints. I’m faster than you over both distances, but I mostly run the 400m, whereas you mostly run the 100m. If you wanted to “prove” that you were faster than me, you could calculate our average race times across both distances combined. Your average would be dominated by all your 100m times, whereas mine would be dominated by my impressive but obviously longer 400m times. You could draw a table just like the ones that we’ve seen already, and boast about your superior average speed.

“But no one would listen to you. Even though there’s once again no functional difference between this example and your kidney stones one, now the hoodwinkery is easy to spot. It’s obvious that you shouldn’t directly combine and compare 100m and 400m sprint times, and so our minds instinctively and immediately go looking for the statistical fiddle.

“There’s another formulation of Simpson’s Paradox that I’d love to talk about - but oh look our hour is up. Do you want to…?”

You pay him another goddamn seven dollars.

“Thank you kindly. Suppose you have an illness, and you’re trying to work out what level of drug dosage will help you recover the fastest. You find the following graph of drug dosage against recovery speed:”

“The overall trend is clearly down. This implies that high drug dosages cause slow recoveries - right? But what if we group people by age?”

“If you’re 20 years old, you want more drugs. If you’re 30 years old, you want more drugs. If you’re 40 years old, you want more drugs. But if you don’t know how old you are, it seems like you want fewer drugs. It’s Simpson’s Paradox again, but wearing a slightly different hat.

“This time the confounder is age. When you say ‘I want fewer drugs so that I recover faster’, what you really mean is ‘I want to be one of these little crosses up in the top-left.’ However, all of those dots in the top-left are 20 years old. If you’re 50 then the way to become one of those dots isn’t to take fewer drugs. It’s to become 20 years old again. There aren’t any dots for 50 year olds who got low doses because doctors know that 50 year olds need high doses in order to recover at all. The graph might become less paradoxical if doctors started experimenting more, but also much much more unethical:

“All this means that you don’t want to ask your doctor to give you a low dose. Instead, you want to be someone who your doctor thinks should have a low dose. Sadly, by the time you’ve been admitted to the ER, you’re all out of agency in that regard.”

You still have twenty-five minutes out of your second one hour statistical session left. You ask Steveington if you can get a $7 * 25/60 = $2.92 refund for the unused time. He says that he’s sorry but he’s unable to bill for fractions of an hour. You fill the time by asking him some questions about Natural Experiments that had been on your mind for a while.

A year later you get a third kidney stone. Sadly there is still no Treatment C, with a 100% success rate for all stones, no questions asked. But you are at least able to choose Treatment B confidently. As the anesthetist puts you under yet again, you feel as content as it is possible to be, given the circumstances.