How to write better sentences: 6 examples

30 Nov 2021

You want to improve your writing. You’ve read a few style guides and remember several of their principles, but you’re not sure what to do next. You know that you should “know your audience” and “omit needless words.” But how?

You need more practice and more examples.

To help, here are 6 real-world sentences that I’ve made shorter, clearer, and more engaging. The improvements cover techniques like resolutions, eliminating pointless phrases, and choosing assertive and kooky words to keep your readers awake. Most of the examples come from essays I’ve written on subjects including computer programming, parenthood, and cryptography, but you don’t need to care about these things in order for the lessons to be useful. The changes are small, but add up quickly over the course of a full essay.

Who am I?

I’m a computer programmer who writes a lot about programming, security, and a few other things. If you’d like some testimonials about why you should take writing advice from me then do what I do when I’m low on self-esteem and search “@robjheaton hilarious” on Twitter.

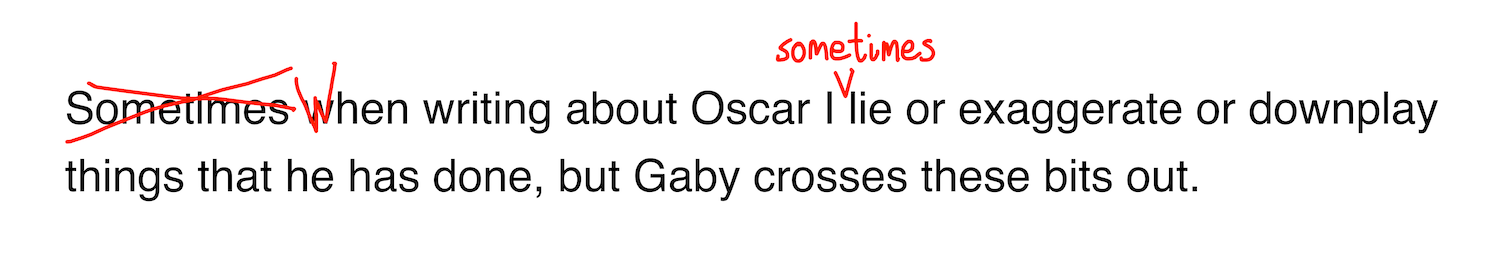

1. Resolve ideas quickly

Ideas in a sentence can come in any order, and related words don’t have to fall near each other. However, putting related clauses far away from each other requires readers to carry unbound information in their head without knowing where it’s going to land. This leaves them with less focus for the words in between.

For example, at the end of a post about parenting I wrote:

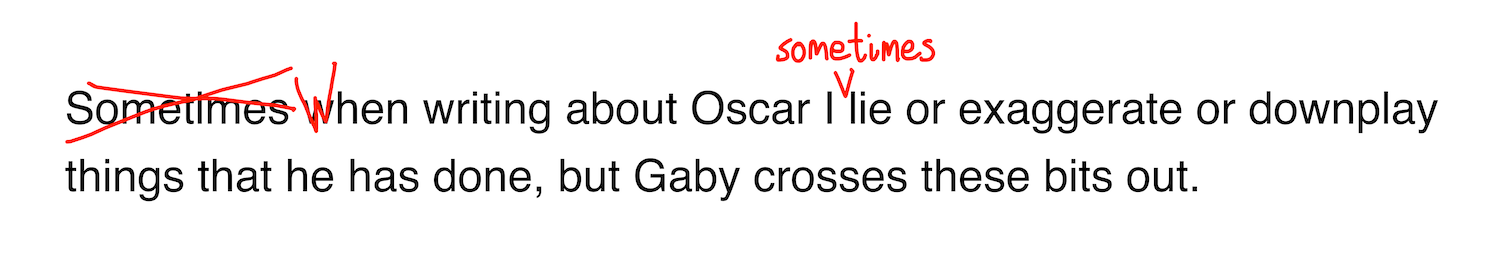

Sometimes when writing about Oscar I lie or exaggerate or downplay things that he has done, but Gaby crosses these bits out.

In this version the reader has to hold the opening “[s]ometimes” in their mind for 5 words before they can bind it to “lie or exaggerate”, which is the thing that I “sometimes” do. When reading the words “when writing about Oscar” the reader has to hold in their mind the fact that whatever follows them is going to be something that only happens occasionally. I think it’s better to push these two elements closer together:

When writing about Oscar I sometimes lie or exaggerate or downplay things that he has done, but Gaby crosses these bits out.

This is a small but I think clear-cut illustration of the benefit of quick resolutions.

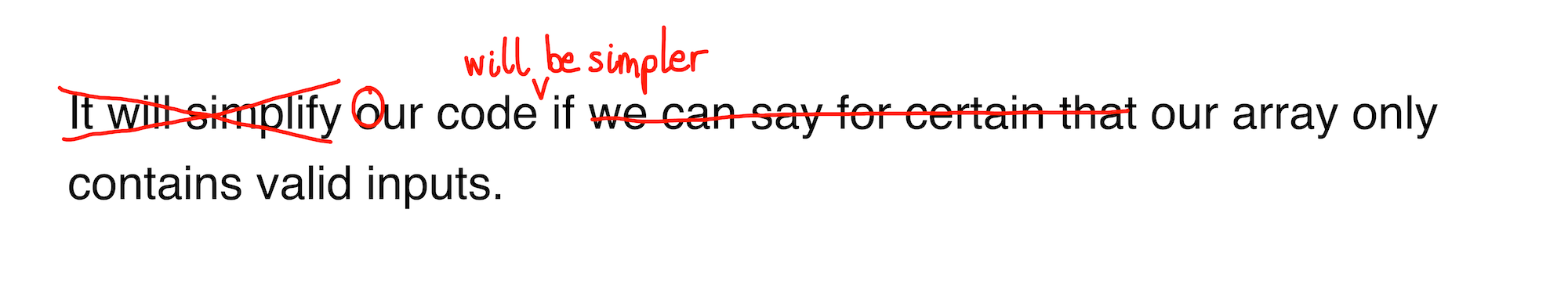

2. Beware the disembodied “it”

Avoid using “it” when it’s not obvious what “it” refers to. It’s a waste of a word and a wooly way to frame a sentence. For example, in a computer programming guide I wrote:

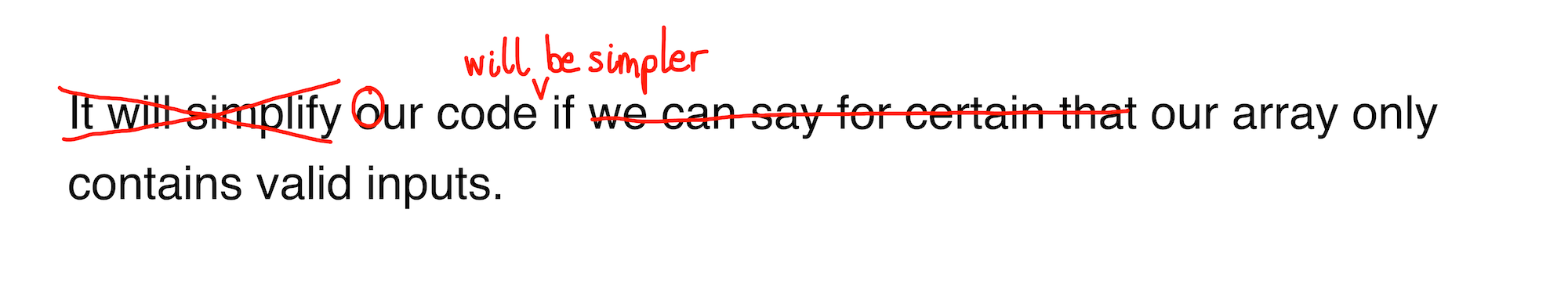

It will simplify our code if we can say for certain that our array only contains valid inputs.

What does that “it” at the start of the sentence refer to? I’m not certain, but I think it’s “the action of saying for certain that our array only contains valid inputs.” We should remove this ambiguity by swapping out the abstract “It will simplify our code if” for the concrete “Our code will be simpler if”. This gives us:

Our code will be simpler if we can say for certain that our array only contains valid inputs.

In addition, “if we can say for certain that” is a lot of words to say little. We can safely get rid of it:

Our code will be simpler if our array only contains valid inputs.

Now our writing is simpler too.

3. Keep editing

Even after several rounds of editing you can still make big improvements. In a blog post called “How I Motivate Myself to Write” by Gergely Orosz, the author describes how he edited one of his own paragraphs. His first attempt was:

In the past I used Hemingway Editor [a piece of writing software] to spot overly complex sentences which I would then proceed to make shorter, but over time I learned to write shorter sentences myself.

He improved this meandering sentence by splitting it into three:

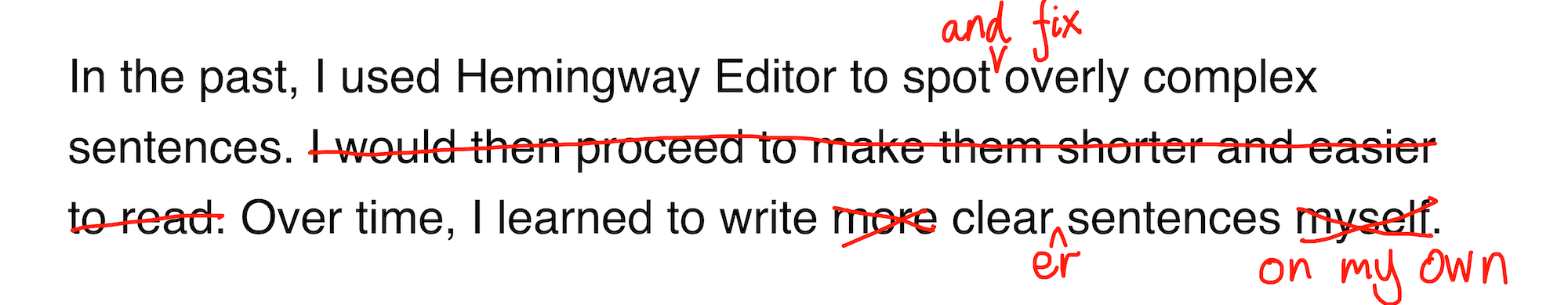

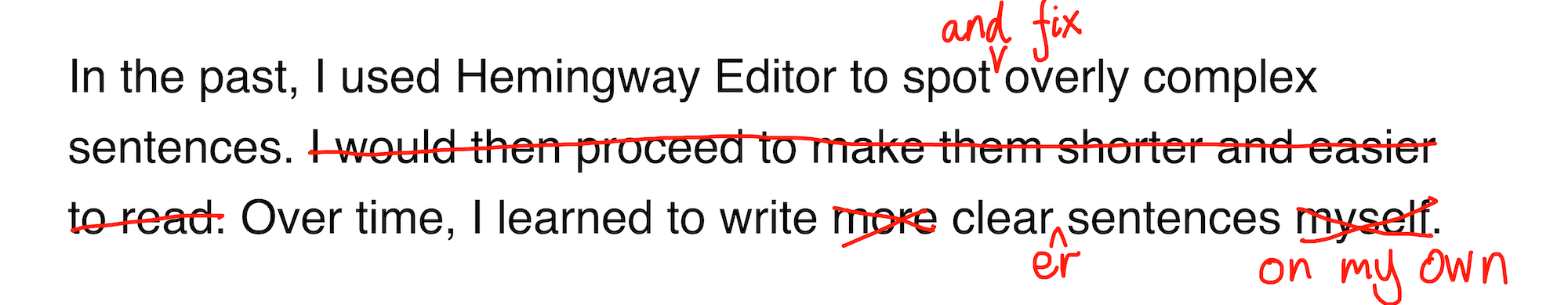

In the past, I used Hemingway Editor to spot overly complex sentences. I would then proceed to make them shorter and easier to read. Over time, I learned to write more clear sentences myself.

This is a good start, but I think we can do better.

First, I dislike the phrase “I would then proceed” in the second sentence. Neither “then” nor “proceed” are useful words. If sentence 2 follows sentence 1 then it’s usually obvious that it happened later. You rarely need a “then”, and we certainly don’t need one here. The phrase “I proceeded to” is similarly meaningless and usually sounds like a poor attempt at being funny, although here I suspect that here it’s just one of the author’s tics.

All of this said, I can’t see a simple way to excise both “then” and “proceed” from the second sentence. In the absence of better options we should at least get rid of one of them, leaving either:

I would proceed to make them shorter and easier to read.

Or:

I would then make them shorter and easier to read.

However, even better would be to rethink whether we need this second sentence at all. The author wants to say that he used Hemingway Editor to identify complex sentences so that he could improve them. I don’t think we need to specify that the way he did this was by making them “shorter and easier to read”; that’s obvious from context. So how about simply:

In the past I used Hemingway Editor to spot and fix overly complex sentences.

We save 12 words and get rid of 2 clunkers. We do have to be careful though. This new wording arguably implies that Hemingway Editor actually rewrote the sentences for the author, whereas I imagine that the author did the rewriting himself before merely asking Hemingway what it thought of the new version. If we were worried about this confusion then I would also be OK with:

In the past I used Hemingway Editor to spot overly complex sentences so that I could fix them.

Or:

In the past I used Hemingway Editor to spot and help fix overly complex sentences.

If we stick with the original redraft then we get:

In the past I used Hemingway Editor to spot and fix overly complex sentences. Over time, I learned to write more clear sentences myself.

Finally, let’s look at the last sentence. It contrasts the author’s past and present methodologies, which is a good technique, but I don’t think that “myself” is the right word to do this. It implies that previously Hemingway Editor was writing the author’s sentences for him, even though we’re pretty sure that it was just helping him out. This is like writing “Previously Gary did my homework. Now I do it myself.”

Since we’re going from a situation where the author and Hemingway were working together to one where the author is working solo, I think that “on my own” is a better contraster. This is more like “Previously Gary and I did my homework together. Now I do it on my own.” Making this substitution and swapping in “clearer” for “more clear” gives my proposed final edit:

In the past I used Hemingway Editor to spot and fix overly complex sentences. Over time I learned to write clearer sentences on my own.

The version that the original author wrote is perfectly reasonable too and the overall post it comes from is very good. I hope it’s clear that I mean this nitpicking as a sincere form of flattery.

4. Use assertive words

Use assertive words that unapologetically say what you mean. Don’t hedge unless you truly are uncertain, because hedging consumes time and words that dilute your point. Hedging can become a default mode of writing, not because you have any important doubts, but because you don’t want to deal with the hassle of someone disagreeing with you even when you think you’re right.

It’s easy to hedge without noticing it. Hedging isn’t just writing “I could be wrong but”; it’s also choosing weak words and mealy-mouthed phrasing. When writing about a cryptography protocol called Off-The-Record Messaging (OTR), I wrote:

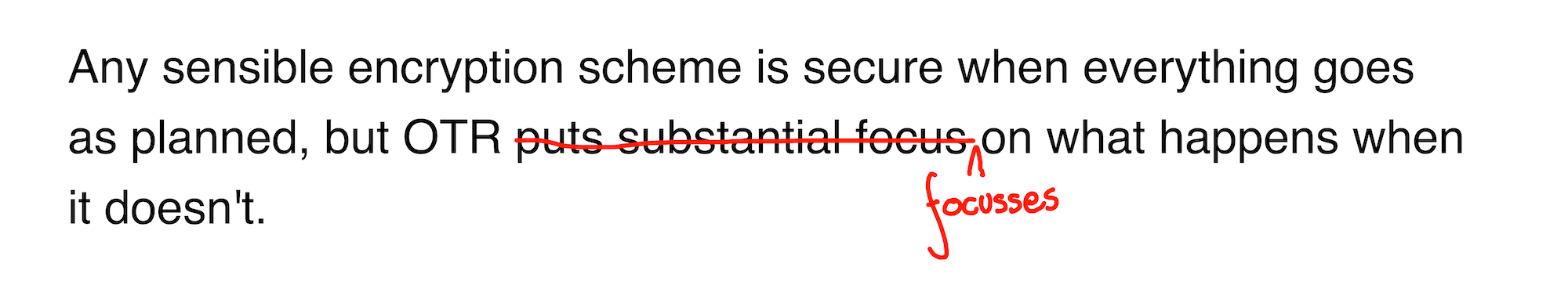

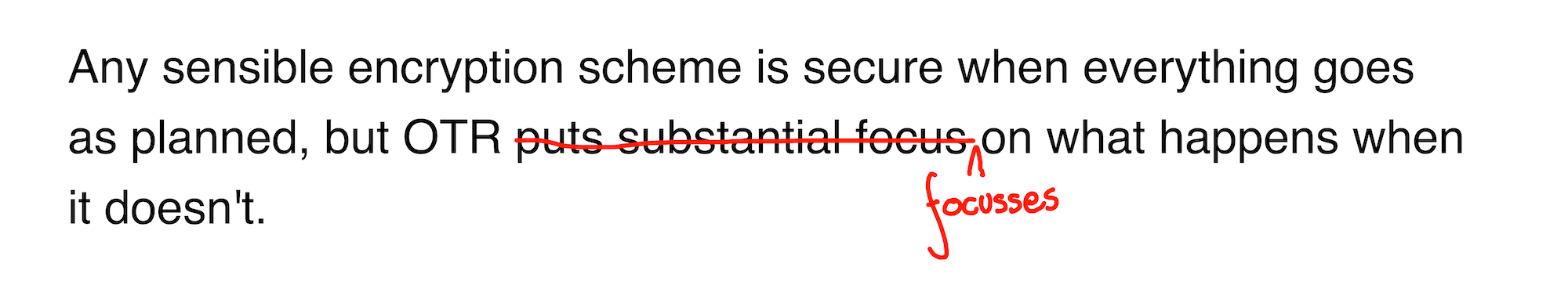

Any sensible encryption scheme is secure when everything goes as planned, but OTR puts substantial focus on what happens when it doesn’t.

Makes sense, but “puts substantial focus on” is unnecessarily hesitant. Why not just “focusses on”?

Any sensible encryption scheme is secure when everything goes as planned, but OTR focusses on what happens when it doesn’t.

When writing the first version of this sentence I was probably scared of “focusses on” because it implies that OTR has a single, main concern. “[P]uts substantial focus on” is comparatively muted, since you can put substantial focus on multiple things. It’s less risky to claim that something is one priority out of many, rather than the top priority. But I do think that what happens when things go wrong is the main thing that OTR cares about, and I shouldn’t be afraid of saying so. The second version is more direct and easier to understand, and I think even conveys better information than the hedged version.

5. Look for quirky words

I like finding quirky words that keep the reader awake. They make for refreshing writing and often carry more meaning than the pedestrian alternatives. These words don’t have to be fancy or anfractuous; I prefer straightforward words in unexpected contexts. Restrained use of a thesaurus often helps.

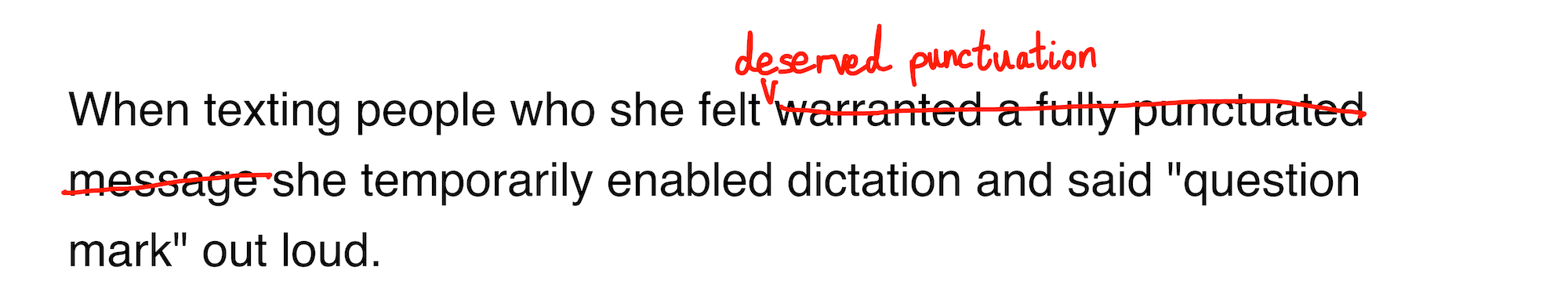

For example, I was writing a post about being a parent. The previous week my wife’s phone had broken and she was unable to press her question mark key. I wanted to write about the fact that for some people she took the effort to add question marks, but for me she didn’t bother. I wrote:

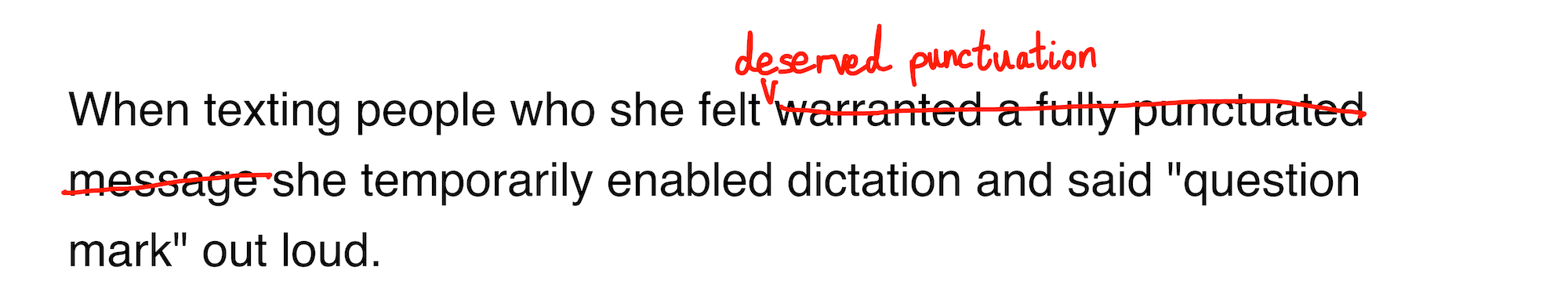

When texting people who she felt required a fully punctuated message she temporarily enabled dictation and said “question mark” out loud.

“people who she felt required a fully punctuated message” felt stodgy, so I changed it to “people who deserved punctuation”:

When texting people who deserved punctuation she temporarily enabled dictation and said “question mark” out loud.

This is an odd use of the word “deserved”, but I think it’s clear that I’m being facetious. It implies the playfulness in our relationship and saves a handsome 4 words and 10 syllables.

6. Use the active voice like your teachers told you

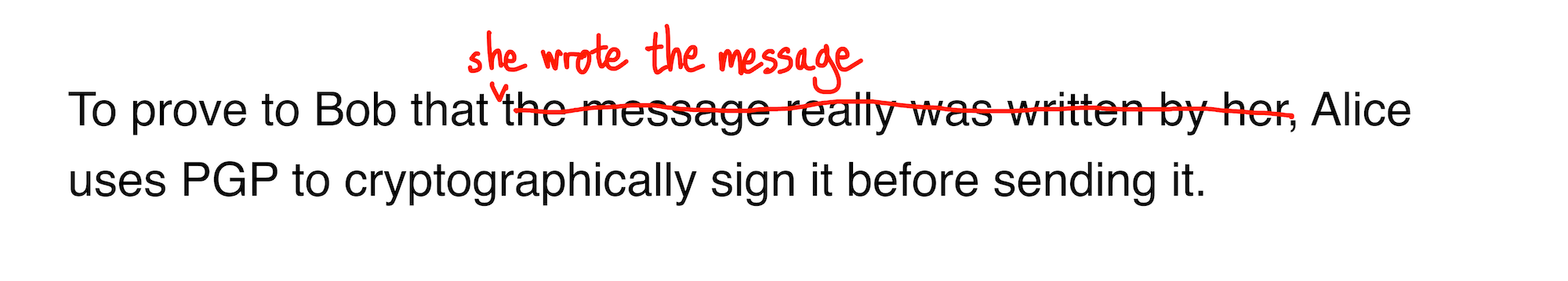

One of the most common pieces of writing advice is to use the active voice (“I did this”) rather than the passive (“this was done by me”). Despite this, I still wrote:

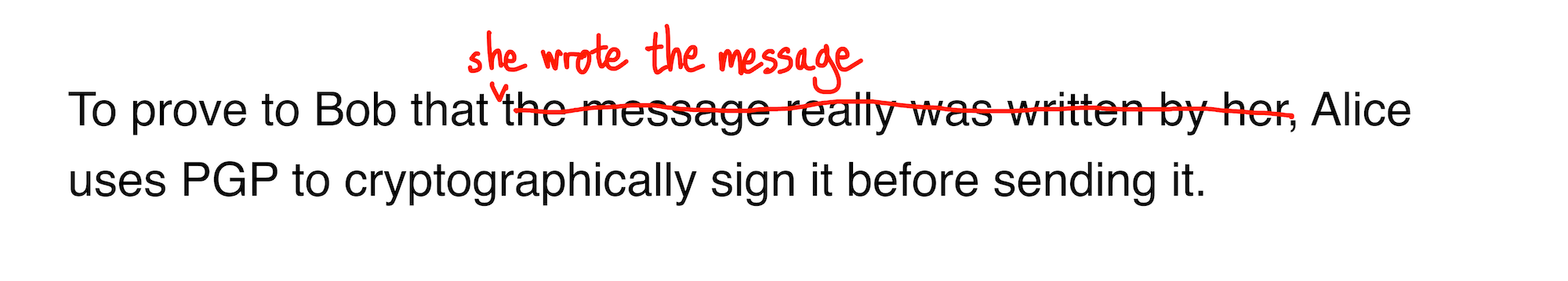

To prove to Bob that the message really was written by her, Alice uses PGP to cryptographically sign it before sending it.

Rewriting this in the active voice is an easy improvement:

To prove to Bob that she wrote the message, Alice uses PGP to cryptographically sign it before sending it.

That said, Bob is sceptical that Alice wrote the message, so perhaps the emphasising “really” in the original version has some value. If we wanted to retain this accent then we could write:

To prove to Bob that she really did write the message, Alice uses PGP to cryptographically sign it before sending it.

However, I think that intensifiers like “really” should be avoided where possible. Better to choose strong words and phrasing that make your emphasis for you.

I hope these examples have been useful. Choose offbeat words when they aren’t distracting, and don’t soften or hedge your language without a reason. Say what you mean. Edit a lot.

Style is always a matter of taste to some degree, and writing firmly about writing exposes an author to criticism and disagreement. If you do object to any of my claimed improvements then please do let me know why, and if you found any examples particularly useful then please let me know about that too.

You want to improve your writing. You’ve read a few style guides and remember several of their principles, but you’re not sure what to do next. You know that you should “know your audience” and “omit needless words.” But how?

You need more practice and more examples.

To help, here are 6 real-world sentences that I’ve made shorter, clearer, and more engaging. The improvements cover techniques like resolutions, eliminating pointless phrases, and choosing assertive and kooky words to keep your readers awake. Most of the examples come from essays I’ve written on subjects including computer programming, parenthood, and cryptography, but you don’t need to care about these things in order for the lessons to be useful. The changes are small, but add up quickly over the course of a full essay.

Who am I?

I’m a computer programmer who writes a lot about programming, security, and a few other things. If you’d like some testimonials about why you should take writing advice from me then do what I do when I’m low on self-esteem and search “@robjheaton hilarious” on Twitter.

1. Resolve ideas quickly

Ideas in a sentence can come in any order, and related words don’t have to fall near each other. However, putting related clauses far away from each other requires readers to carry unbound information in their head without knowing where it’s going to land. This leaves them with less focus for the words in between.

For example, at the end of a post about parenting I wrote:

Sometimes when writing about Oscar I lie or exaggerate or downplay things that he has done, but Gaby crosses these bits out.

In this version the reader has to hold the opening “[s]ometimes” in their mind for 5 words before they can bind it to “lie or exaggerate”, which is the thing that I “sometimes” do. When reading the words “when writing about Oscar” the reader has to hold in their mind the fact that whatever follows them is going to be something that only happens occasionally. I think it’s better to push these two elements closer together:

When writing about Oscar I sometimes lie or exaggerate or downplay things that he has done, but Gaby crosses these bits out.

This is a small but I think clear-cut illustration of the benefit of quick resolutions.

2. Beware the disembodied “it”

Avoid using “it” when it’s not obvious what “it” refers to. It’s a waste of a word and a wooly way to frame a sentence. For example, in a computer programming guide I wrote:

It will simplify our code if we can say for certain that our array only contains valid inputs.

What does that “it” at the start of the sentence refer to? I’m not certain, but I think it’s “the action of saying for certain that our array only contains valid inputs.” We should remove this ambiguity by swapping out the abstract “It will simplify our code if” for the concrete “Our code will be simpler if”. This gives us:

Our code will be simpler if we can say for certain that our array only contains valid inputs.

In addition, “if we can say for certain that” is a lot of words to say little. We can safely get rid of it:

Our code will be simpler if our array only contains valid inputs.

Now our writing is simpler too.

3. Keep editing

Even after several rounds of editing you can still make big improvements. In a blog post called “How I Motivate Myself to Write” by Gergely Orosz, the author describes how he edited one of his own paragraphs. His first attempt was:

In the past I used Hemingway Editor [a piece of writing software] to spot overly complex sentences which I would then proceed to make shorter, but over time I learned to write shorter sentences myself.

He improved this meandering sentence by splitting it into three:

In the past, I used Hemingway Editor to spot overly complex sentences. I would then proceed to make them shorter and easier to read. Over time, I learned to write more clear sentences myself.

This is a good start, but I think we can do better.

First, I dislike the phrase “I would then proceed” in the second sentence. Neither “then” nor “proceed” are useful words. If sentence 2 follows sentence 1 then it’s usually obvious that it happened later. You rarely need a “then”, and we certainly don’t need one here. The phrase “I proceeded to” is similarly meaningless and usually sounds like a poor attempt at being funny, although here I suspect that here it’s just one of the author’s tics.

All of this said, I can’t see a simple way to excise both “then” and “proceed” from the second sentence. In the absence of better options we should at least get rid of one of them, leaving either:

I would proceed to make them shorter and easier to read.

Or:

I would then make them shorter and easier to read.

However, even better would be to rethink whether we need this second sentence at all. The author wants to say that he used Hemingway Editor to identify complex sentences so that he could improve them. I don’t think we need to specify that the way he did this was by making them “shorter and easier to read”; that’s obvious from context. So how about simply:

In the past I used Hemingway Editor to spot and fix overly complex sentences.

We save 12 words and get rid of 2 clunkers. We do have to be careful though. This new wording arguably implies that Hemingway Editor actually rewrote the sentences for the author, whereas I imagine that the author did the rewriting himself before merely asking Hemingway what it thought of the new version. If we were worried about this confusion then I would also be OK with:

In the past I used Hemingway Editor to spot overly complex sentences so that I could fix them.

Or:

In the past I used Hemingway Editor to spot and help fix overly complex sentences.

If we stick with the original redraft then we get:

In the past I used Hemingway Editor to spot and fix overly complex sentences. Over time, I learned to write more clear sentences myself.

Finally, let’s look at the last sentence. It contrasts the author’s past and present methodologies, which is a good technique, but I don’t think that “myself” is the right word to do this. It implies that previously Hemingway Editor was writing the author’s sentences for him, even though we’re pretty sure that it was just helping him out. This is like writing “Previously Gary did my homework. Now I do it myself.”

Since we’re going from a situation where the author and Hemingway were working together to one where the author is working solo, I think that “on my own” is a better contraster. This is more like “Previously Gary and I did my homework together. Now I do it on my own.” Making this substitution and swapping in “clearer” for “more clear” gives my proposed final edit:

In the past I used Hemingway Editor to spot and fix overly complex sentences. Over time I learned to write clearer sentences on my own.

The version that the original author wrote is perfectly reasonable too and the overall post it comes from is very good. I hope it’s clear that I mean this nitpicking as a sincere form of flattery.

4. Use assertive words

Use assertive words that unapologetically say what you mean. Don’t hedge unless you truly are uncertain, because hedging consumes time and words that dilute your point. Hedging can become a default mode of writing, not because you have any important doubts, but because you don’t want to deal with the hassle of someone disagreeing with you even when you think you’re right.

It’s easy to hedge without noticing it. Hedging isn’t just writing “I could be wrong but”; it’s also choosing weak words and mealy-mouthed phrasing. When writing about a cryptography protocol called Off-The-Record Messaging (OTR), I wrote:

Any sensible encryption scheme is secure when everything goes as planned, but OTR puts substantial focus on what happens when it doesn’t.

Makes sense, but “puts substantial focus on” is unnecessarily hesitant. Why not just “focusses on”?

Any sensible encryption scheme is secure when everything goes as planned, but OTR focusses on what happens when it doesn’t.

When writing the first version of this sentence I was probably scared of “focusses on” because it implies that OTR has a single, main concern. “[P]uts substantial focus on” is comparatively muted, since you can put substantial focus on multiple things. It’s less risky to claim that something is one priority out of many, rather than the top priority. But I do think that what happens when things go wrong is the main thing that OTR cares about, and I shouldn’t be afraid of saying so. The second version is more direct and easier to understand, and I think even conveys better information than the hedged version.

5. Look for quirky words

I like finding quirky words that keep the reader awake. They make for refreshing writing and often carry more meaning than the pedestrian alternatives. These words don’t have to be fancy or anfractuous; I prefer straightforward words in unexpected contexts. Restrained use of a thesaurus often helps.

For example, I was writing a post about being a parent. The previous week my wife’s phone had broken and she was unable to press her question mark key. I wanted to write about the fact that for some people she took the effort to add question marks, but for me she didn’t bother. I wrote:

When texting people who she felt required a fully punctuated message she temporarily enabled dictation and said “question mark” out loud.

“people who she felt required a fully punctuated message” felt stodgy, so I changed it to “people who deserved punctuation”:

When texting people who deserved punctuation she temporarily enabled dictation and said “question mark” out loud.

This is an odd use of the word “deserved”, but I think it’s clear that I’m being facetious. It implies the playfulness in our relationship and saves a handsome 4 words and 10 syllables.

6. Use the active voice like your teachers told you

One of the most common pieces of writing advice is to use the active voice (“I did this”) rather than the passive (“this was done by me”). Despite this, I still wrote:

To prove to Bob that the message really was written by her, Alice uses PGP to cryptographically sign it before sending it.

Rewriting this in the active voice is an easy improvement:

To prove to Bob that she wrote the message, Alice uses PGP to cryptographically sign it before sending it.

That said, Bob is sceptical that Alice wrote the message, so perhaps the emphasising “really” in the original version has some value. If we wanted to retain this accent then we could write:

To prove to Bob that she really did write the message, Alice uses PGP to cryptographically sign it before sending it.

However, I think that intensifiers like “really” should be avoided where possible. Better to choose strong words and phrasing that make your emphasis for you.

I hope these examples have been useful. Choose offbeat words when they aren’t distracting, and don’t soften or hedge your language without a reason. Say what you mean. Edit a lot.

Style is always a matter of taste to some degree, and writing firmly about writing exposes an author to criticism and disagreement. If you do object to any of my claimed improvements then please do let me know why, and if you found any examples particularly useful then please let me know about that too.