It's not cheating if you write the video game solver yourself

11 Mar 2025

My wife and two little boys sometimes go on trips to see friends or family for whom my presence isn’t strictly required. While my wife books the flights I make a show of weighing up my options and asking if it’s really OK if I don’t come. Eventually I’m persuaded that it truly would be the best thing for all of us for me to have five to seven days to myself with no nappies and all Nintendo.

My wife hits the “Pay Now” button and when the confirmation email comes through I call my secretary and tell him to clear my calendar. When no one answers I remember that I have neither a secretary nor all that much going on, so instead I find a prestige TV series, a selection of local takeaway menus, and a short but immersive video game. This time I messaged my buddies and asked them what I should play. Steve gushed about a game called Cocoon; Morris said that he’d played it a year ago and it was “alright.” Sold.

One month later there were hugs, kisses, wave goodbye to taxi, shut the door, where’s the HDMI cable, how did it get under the sink, do I have a Nintendo Account, what’s my password, whatever I’ll make a new one, right let’s do this, estimated download time 45 minutes, start on tax returns, am I relaxed yet?

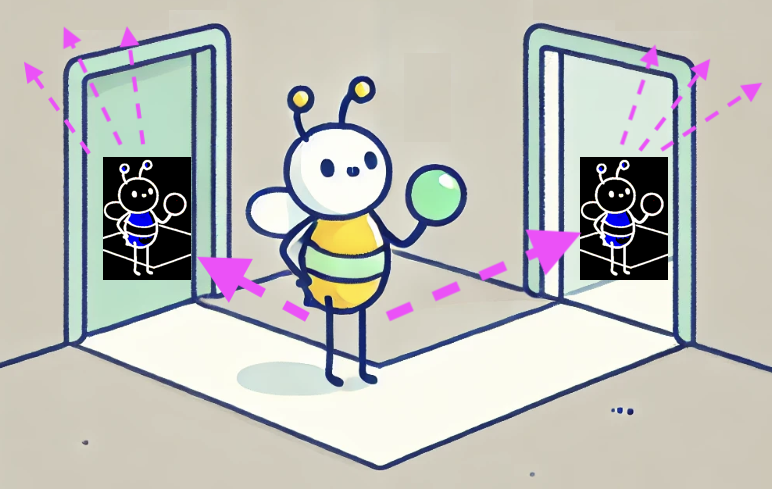

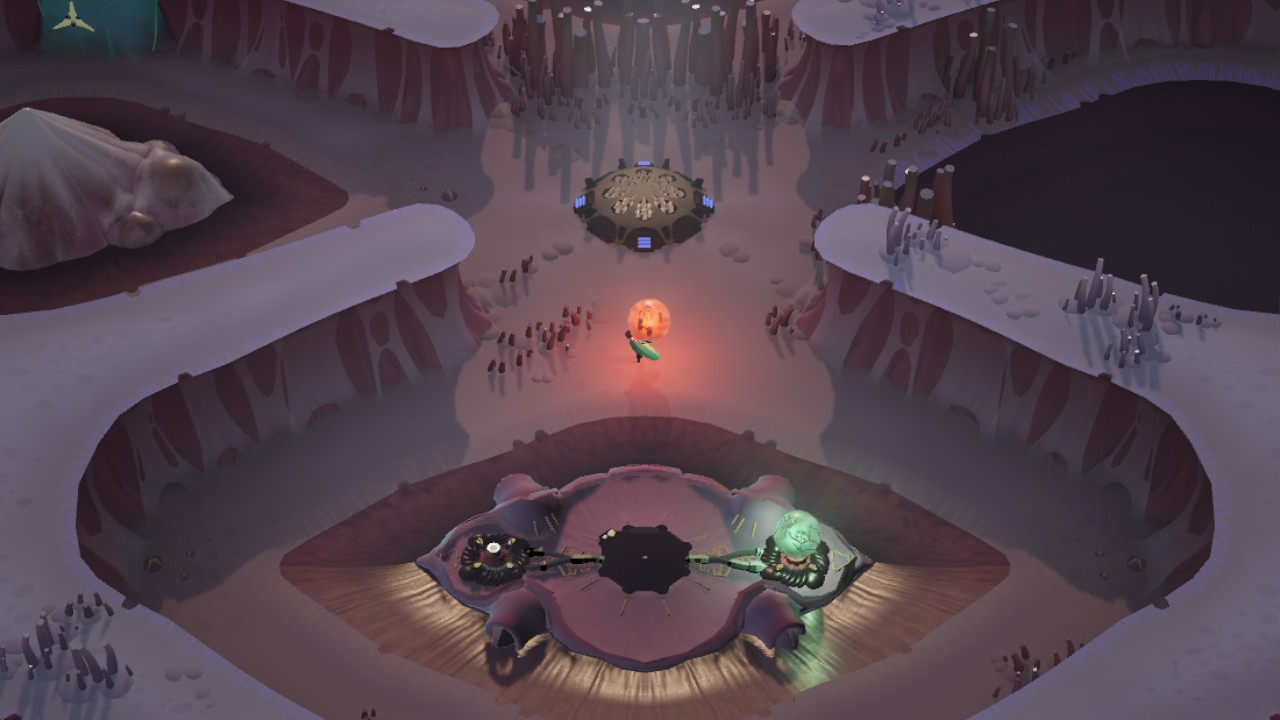

Eventually I was able to boot up Cocoon. I learned that I was going to play as a little bee guy who has to solve artsy puzzles in a lonely, abstract world for no adequately explained reason. Bee guy makes his way through the world using four glowing orbs. He can pick orbs up, carry them around, and put them back down on switches in order to open doors and unfold bridges - standard orb stuff. However, bee guy soon learns that the orbs also contain other worlds, which he can jump in and out of to help with his puzzles. If he jumps inside one orb-world whilst carrying another one then he can put orb-worlds inside each other. He can even - towards the end - put a world inside itself. Conundrums ensue.

By the end of Day 1 of my vacation I was having about three-quarters as much fun as I’d hoped. Cocoon’s atmosphere was absorbing and its puzzles made me smile; I only wish there had been a little bit of a story and not just a fuzzy metaphor for entropy and decay. Still, I kept going, trekking through crumbling ruins and overbearing symbolism. By the end of Day 2 I was 51% through the game. I started the next puzzle and got completely stuck. I was surely just tired, I thought, so I watched an episode of The Sopranos and went to bed. The next morning I got up at 6am, made some coffee, and went into my office to crack on. But I was still stuck. I spent an hour filling a bin bag with toys that I didn’t like, since no one was around to stop me. I tried again. Still stuck.

Then I realised. I didn’t know how to solve the puzzle, but I did know how to write a computer program to solve it for me. That would probably be even more fun, and I could argue that it didn’t actually count as cheating. I didn’t want the solution to reveal itself to me before I’d had a chance to systematically hunt it down, so I dived across the room to turn off the console.

I wanted to have a shower but I was worried that if I did then inspiration might strike and I might figure out the answer myself. So I ran upstairs to my office, hit my Pomodoro timer, scrolled Twitter to warm up my brain, took a break, made a JIRA board, Slacked my wife a status update, no reply, she must be out of signal. Finally I fired up my preferred assistive professional tool. Time to have a real vacation.

How I wrote a Cocoon solver

In order to write a Cocoon solver, I needed to:

- Model the game’s logic using a Finite State Machine

- Use this model to work out the sequence of actions that would get me from a puzzle’s start to its end

1. Model the game’s logic

Cocoon’s mechanics are simple but elegant. In the first level you find an orange orb sitting on a stand. You pick it up, obviously, and start to carry it around. You come to a gate with an orb-stand next to it. You put the orb down on the stand and the gate opens. You pick it up again and continue through the gate.

Eventually you come to a small reflecting pool with a special-looking orb-stand in the middle. There’s no obvious path forward, so you put your orange orb down on the stand. You stand next to it and press A, because that’s the only button in the game that does anything. You watch yourself dive into the orb, and land in another world. You’re now inside the orange orb. You start to walk, You find a new, green orb, which you use to keep solving puzzles and opening doors and moving forwards through the orange orb-world. Throughout the course of the game you find a total of four orbs, and the final puzzles require you to lug them all around and dive in and out of them in just the right order to get across the next bridge.

An example: in one puzzle you need to bring your red orb to the top of a vine so that you can use it to reveal a magic walkway to get to the next area. However, you can only climb up vines while holding your green orb, and you can only hold one orb at a time. This means that you can’t carry the red orb up the vine. The solution is therefore to pick up the red orb, dive inside the green orb, drop the red orb, jump out, use the green orb to climb the vine, dive back inside the green orb, retrieve the red orb, and jump back out.

In order for my solver to analyse Cocoon, it would need to be able to programatically manipulate a copy of it. My solver would need to know how the world was laid out, what actions were allowed, and whether it had finished solving its puzzle yet. The easiest way to do this wasn’t to have the solver interact with the real game, but to instead write a new, stripped-back copy of it that contained all its logic but none of the graphics.

This was made easier by the fact that each of the puzzles that I got stuck on could be represented as a finite state machine. A finite state machine is a system that can be in exactly one of a finite number of states at any given time. The system is able to transition between some pairs of states using a set of known rules.

Most games with a large 3-D world can’t be modelled as a FSM because they have too many possible states and too many possible transitions. The player can be in a near-infinite number of slightly different locations; so can their enemies. The player might have a huge number of items they could be carrying and past actions they could have taken, each of which could affect the world in some important way. Some parts of the game may depend on timing and agility, which are hard to represent in a FSM. In most game levels there’s too much going on for a simple model like an FSM.

However, Cocoon’s is a simple world. There are no enemies. The only items you can carry are 4 orbs. And whilst its 3-D landscape is lovely to look at, it masks a simple topology that can be modelled as a small graph - a collection of nodes (important locations like orbs and switches) and edges (pathways that connect nodes that are immediately accessible from each other). Beyond these characteristics, the exact layout of the world rarely matters.

This means that a “state” in Cocoon is easy to define and manage. A state is defined by the combination of:

- The node you’re nearest

- Which orb you’re holding

- Where the other orbs are

- (possibly a few other things, depending on the exact puzzle)

Transitions between states are similarly constrained. Players can transition between game states via only a small set of actions, such as:

- Walking to an adjacent node

- Picking up or putting down an orb

- Jumping in or out of an orb

This means that it’s relatively simple to write a program that:

- Defines the layout of a puzzle world

- Defines the state that the game is currently in

- Is able to transition between states

- Knows how to identify a goal state

Once I’d written this program, I had a representation of the game that I could programmatically manipulate. I could tell my game to do things like “take such-and-such an action” or “tell me all the possible next actions that can be taken from the current state.” This meant that I could use my simplified game to analyse and solve the real one.

2. Work out how to get from the start to the goal state

To solve a puzzle I needed to find a sequence of actions that would take me from the puzzle’s start state to its goal state (for example, opening a door). This was a job for an algorithm called Breadth-First Search (BFS).

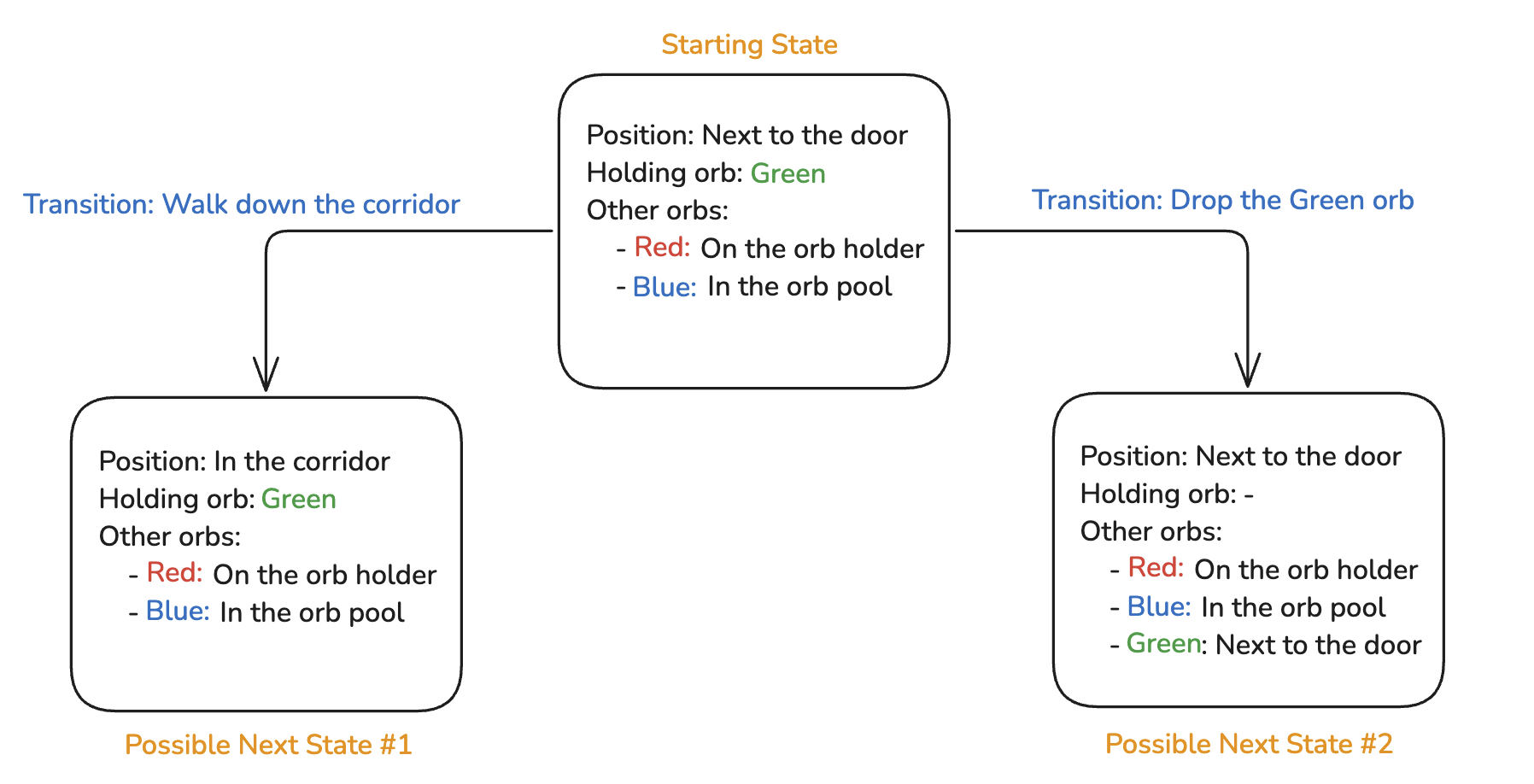

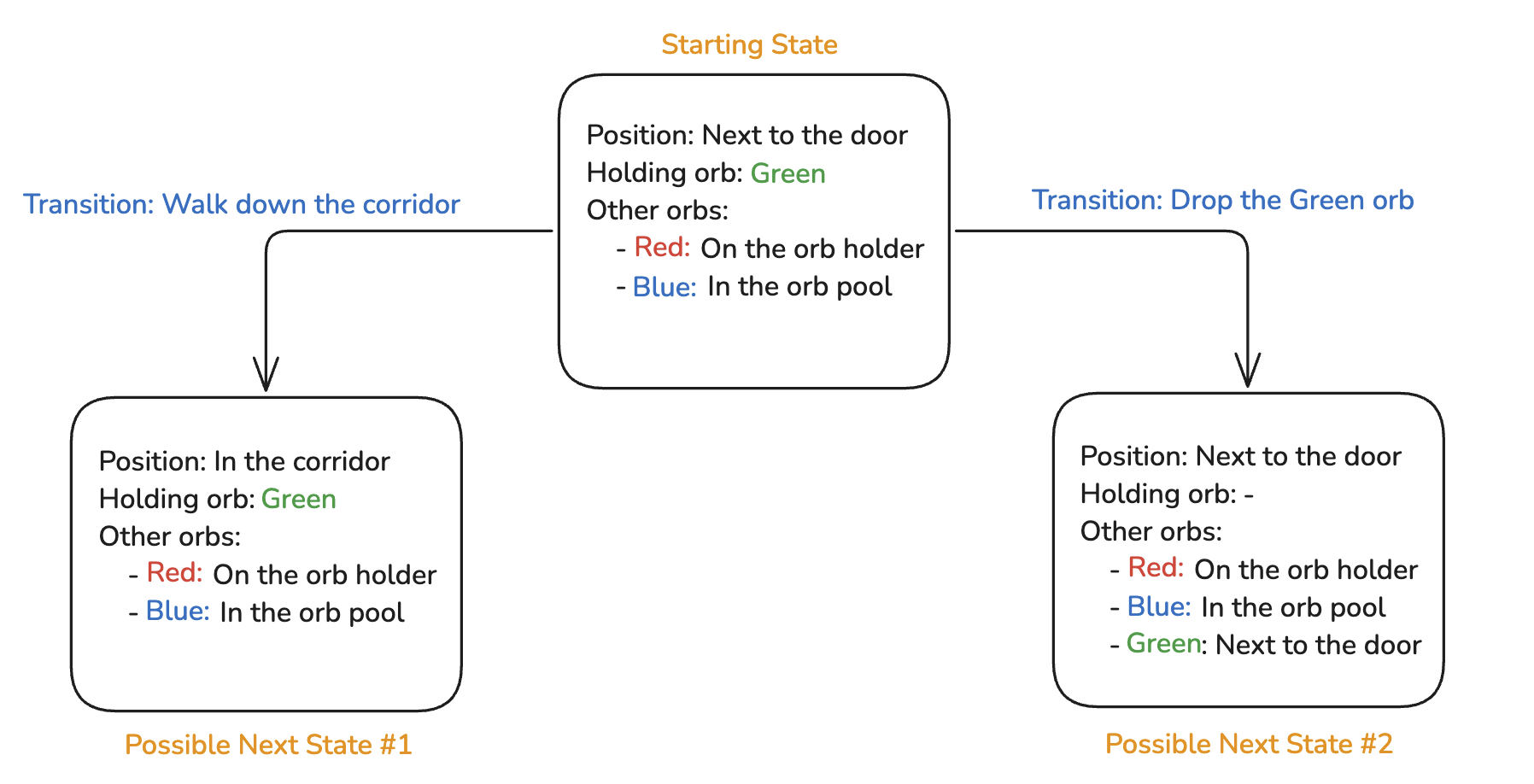

BFS starts at an initial state in an FSM and simultaneously takes a step to every new state that can be reached from it. For example, suppose that a puzzle starts with bee guy holding the green orb, next to a door and to a corridor to another section.

My solver takes steps both through the door and down the corridor, and begins keeping track of each path. From each of these new states, it takes another step to each further state that can be reached from them.

It keeps stepping and tracking the expanding number of paths that it’s exploring, until one of its paths reaches a goal state (for example, a state in which a particular orb is on a particular stand, which opens a bridge to the next area). At this point the solver stops, and returns the path that led to the goal state. Because the solver takes a single step down every possible path at once, the first path to the goal state that it finds is guaranteed to be the shortest one possible.

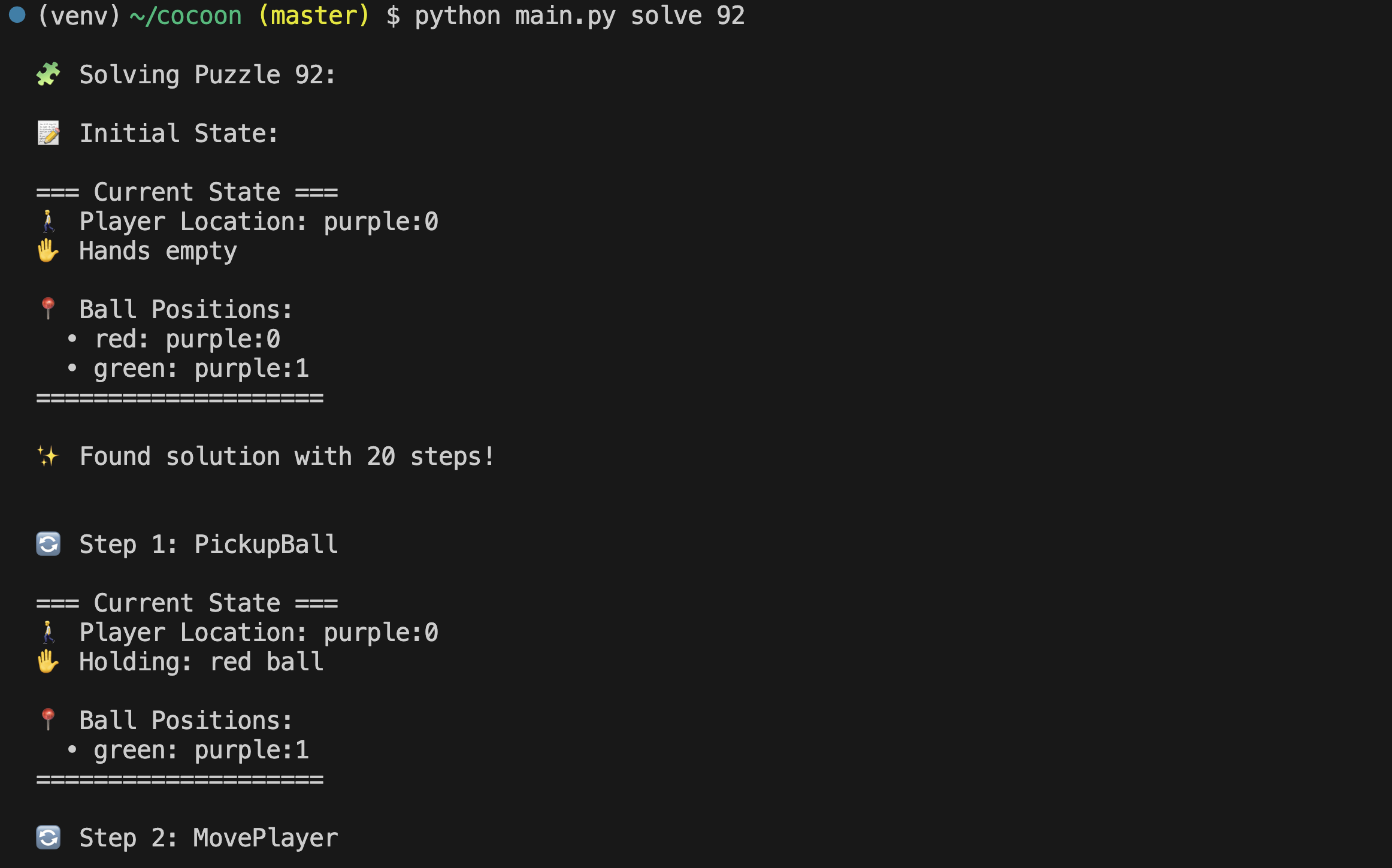

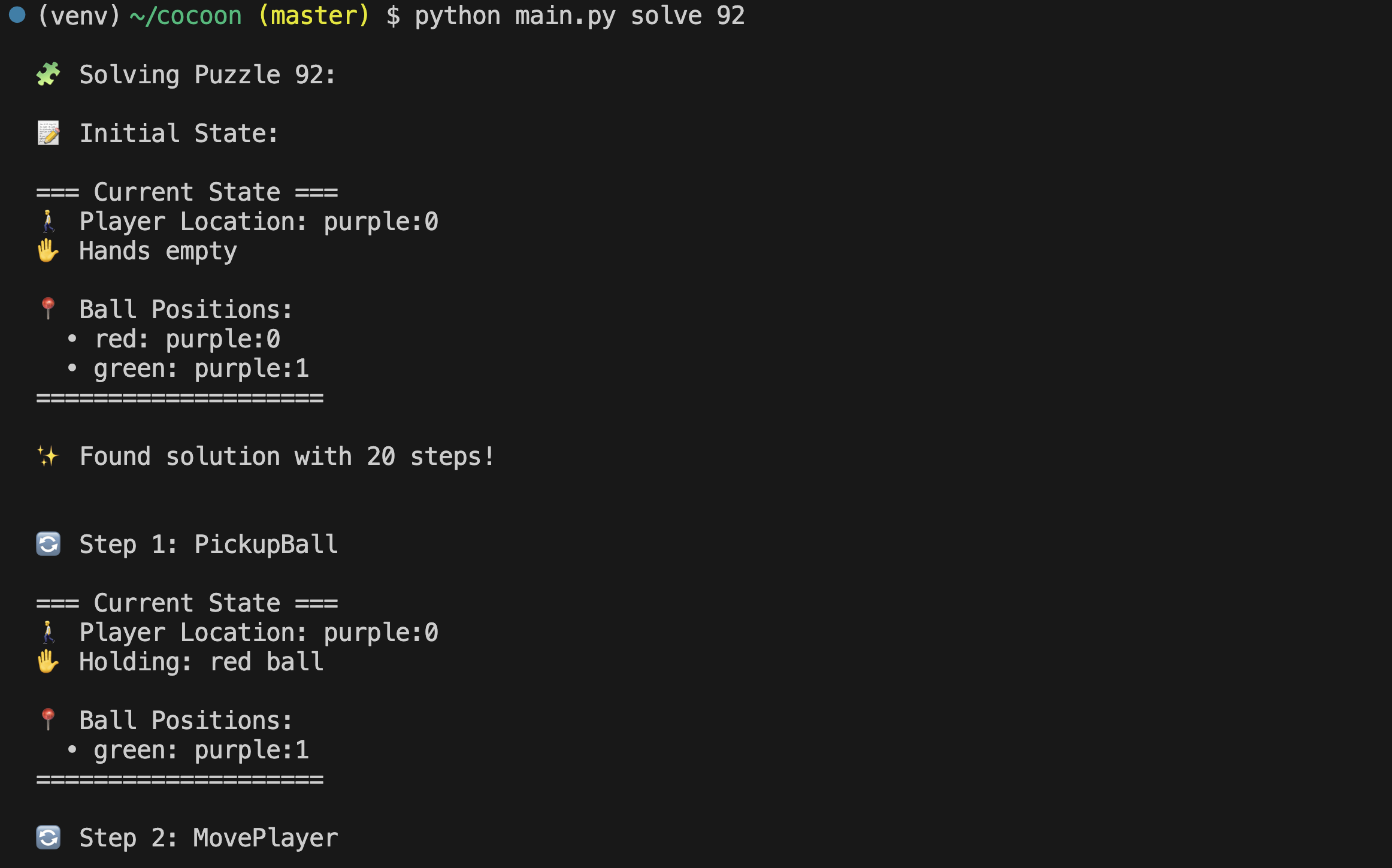

I can then input the sequence of actions that my solver returned into the real game (for example: pick up red orb, walk to orb holder, put down red orb, etc), and move on to the next level, without having to do any thinking whatsoever. Here’s my code.

How hard are these puzzles really?

My solver stops as soon as it has reached the goal state. However, I was also interested in fully mapping out every possible sequence of actions one could take inside a puzzle. I wanted to see how big and hard the puzzles actually are.

To do this I wrote a script that explores every possible state and transition. It keeps stepping through states transitions, even after one of its paths has reached a goal state. It only stops when none of the paths it’s exploring have any available actions that lead to a new state that it hasn’t seen before.

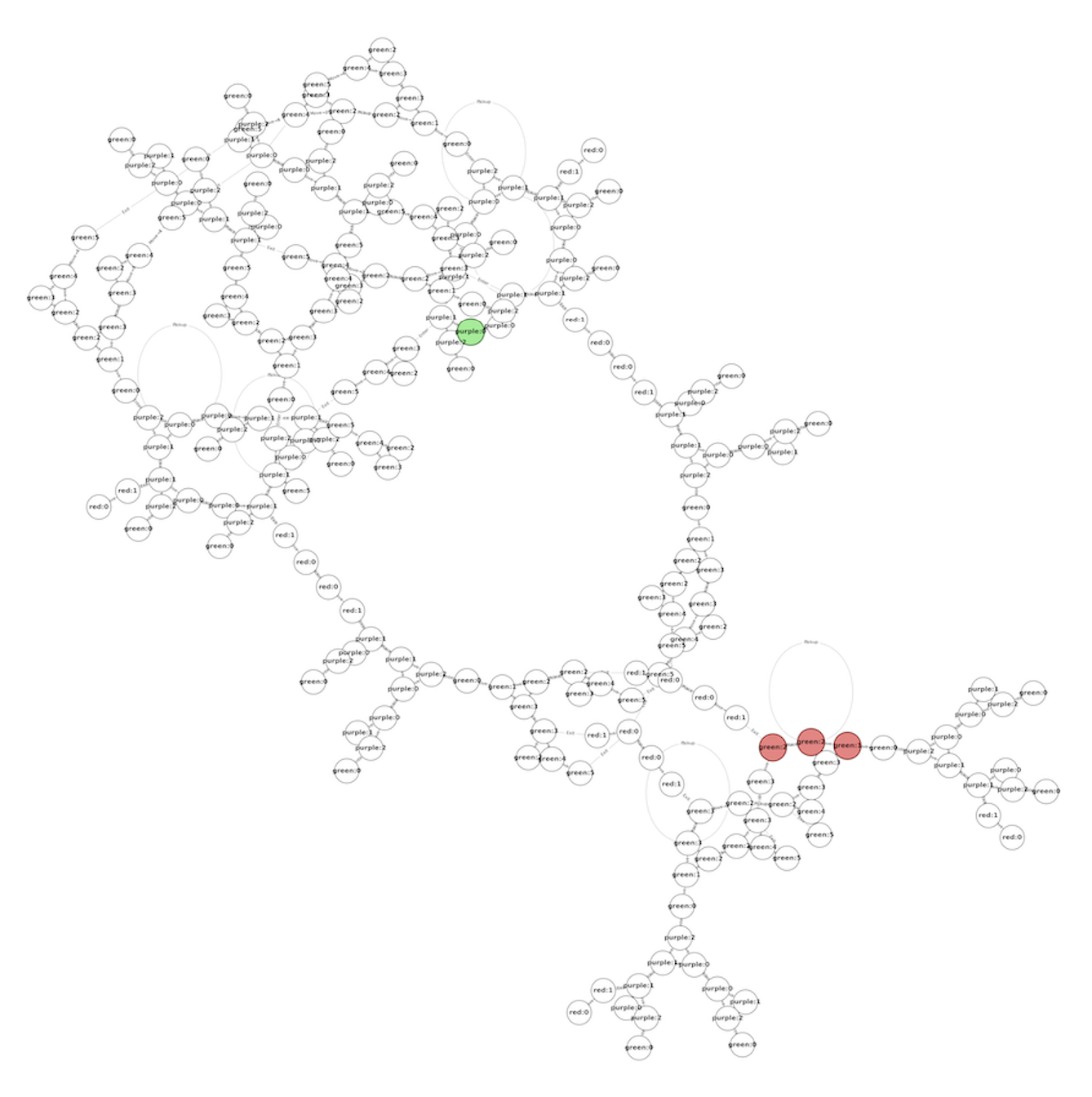

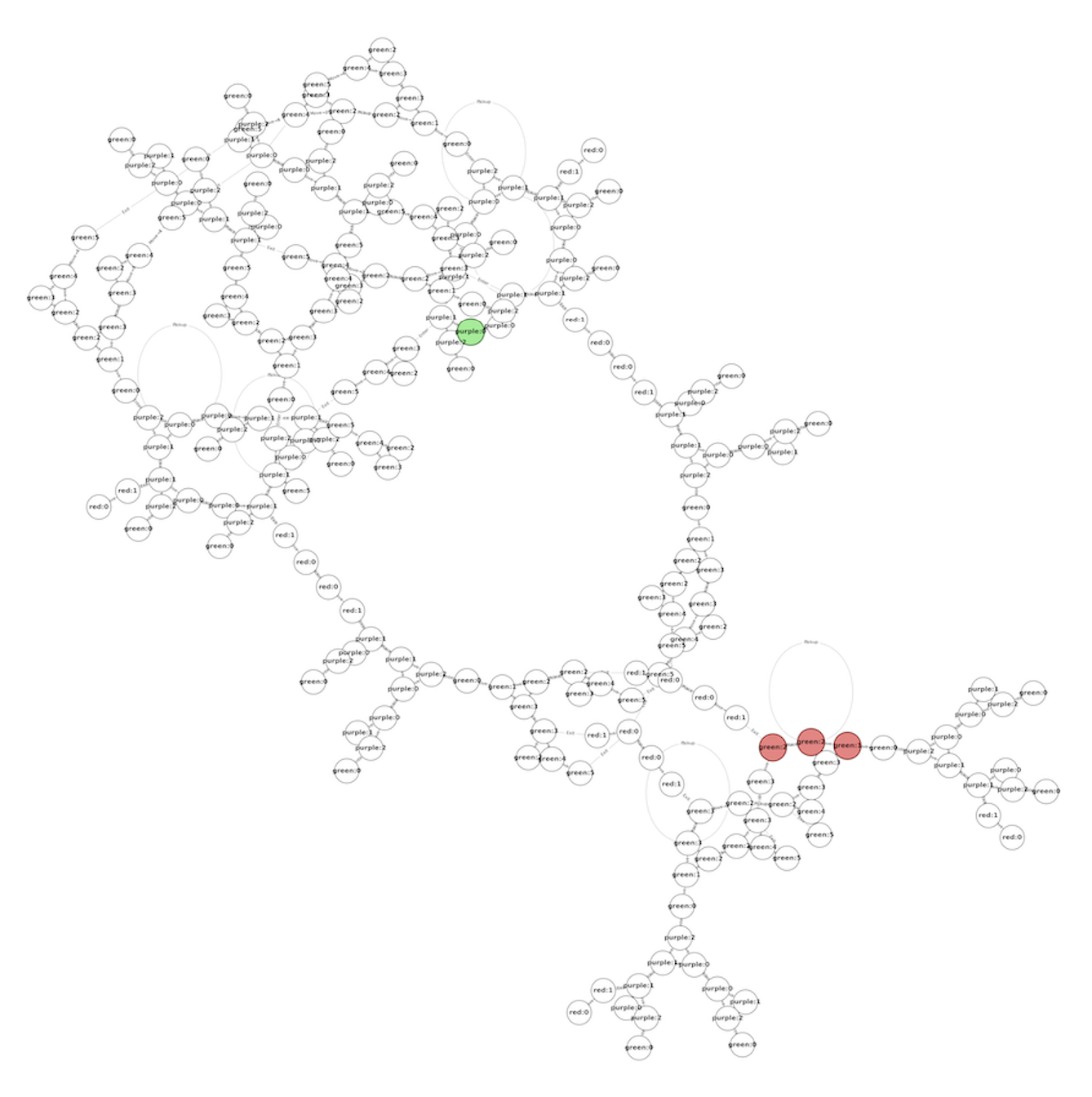

This script generates a new graph, in which each node is a state and each edge is a transition. The graph shows every single sequence of actions that you can take inside the puzzle. For example, here’s the puzzle that I found hardest, represented as a graph of states and transitions:

Drawing a fully-expanded FSM graph like this shows how small and simple Cocoon’s puzzles really are once you write them down. That path on the right, between the green and red nodes, requires you to put one orb inside another orb, then inside another orb, and then shuffle them around just-so. This is a counter-intuitive strategy and hard to find if you’re playing the game like a normal person.

However, writing everything down makes it obvious. Writing everything down makes all actions visible and strips away all of the misleading heuristics that make humans focus on some strategies and completely miss others. It reduces a puzzle to “find a path from the green dot to one of the red dots,” as you saw above, which can be solved by a moderately gifted two year-old. To be very facetious, Cocoon is a fluffy layer of graphics and game mechanics on top of an unbelievably simple maze.

This isn’t meant as a knock on the game. Cocoon is a tidy mind-bender that wasn’t designed to withstand exhaustive search. If you write a program to solve your Cocoon puzzles for you then you’re only cheating yourself. Or at least, you would be if writing such a program wasn’t so much fun.

Life lessons

Real life isn’t a finite state machine though. All my solver really proves is that small, low-dimensional problems can easily be solved using exhaustive search. By contrast, the world has an infinite number of states. It’s hard to be sure which properties are important, and the allowed transitions between states are terribly defined. No problem of any importance can be reduced to a tiny graph, which means that even the most determined two year-old won’t be able to help with any of the big challenges in your life.

However, you don’t need to fully explore all possible solutions in order to benefit from systematic search. As I’d feared, the process of writing my solver forced me to consider the game with so much rigour that I’d solved all 3 challenges that I used it for before I’d finished programming them in. When I came to encode every location and transition on the map in my program I was forced to pay attention to each of them individually for at least a few seconds, even the ones that the game had tricked me into ignoring. This helped me see that some of the nodes and actions that I’d thought were irrelevant were actually the key to the whole thing.

That evening I talked to my family on the phone. I showed them all the diagrams I’d created and all the fun I’d had. They showed me pictures of them inside St. Peter’s Basilica. My son asked if I’d beaten my game. I explained that I’d transcended it by creating a mathematical representation of its entire possibility space. He asked if that meant “no.”

Here’s the code to my solver, but you should really just play the game properly.

My wife and two little boys sometimes go on trips to see friends or family for whom my presence isn’t strictly required. While my wife books the flights I make a show of weighing up my options and asking if it’s really OK if I don’t come. Eventually I’m persuaded that it truly would be the best thing for all of us for me to have five to seven days to myself with no nappies and all Nintendo.

My wife hits the “Pay Now” button and when the confirmation email comes through I call my secretary and tell him to clear my calendar. When no one answers I remember that I have neither a secretary nor all that much going on, so instead I find a prestige TV series, a selection of local takeaway menus, and a short but immersive video game. This time I messaged my buddies and asked them what I should play. Steve gushed about a game called Cocoon; Morris said that he’d played it a year ago and it was “alright.” Sold.

One month later there were hugs, kisses, wave goodbye to taxi, shut the door, where’s the HDMI cable, how did it get under the sink, do I have a Nintendo Account, what’s my password, whatever I’ll make a new one, right let’s do this, estimated download time 45 minutes, start on tax returns, am I relaxed yet?

Eventually I was able to boot up Cocoon. I learned that I was going to play as a little bee guy who has to solve artsy puzzles in a lonely, abstract world for no adequately explained reason. Bee guy makes his way through the world using four glowing orbs. He can pick orbs up, carry them around, and put them back down on switches in order to open doors and unfold bridges - standard orb stuff. However, bee guy soon learns that the orbs also contain other worlds, which he can jump in and out of to help with his puzzles. If he jumps inside one orb-world whilst carrying another one then he can put orb-worlds inside each other. He can even - towards the end - put a world inside itself. Conundrums ensue.

By the end of Day 1 of my vacation I was having about three-quarters as much fun as I’d hoped. Cocoon’s atmosphere was absorbing and its puzzles made me smile; I only wish there had been a little bit of a story and not just a fuzzy metaphor for entropy and decay. Still, I kept going, trekking through crumbling ruins and overbearing symbolism. By the end of Day 2 I was 51% through the game. I started the next puzzle and got completely stuck. I was surely just tired, I thought, so I watched an episode of The Sopranos and went to bed. The next morning I got up at 6am, made some coffee, and went into my office to crack on. But I was still stuck. I spent an hour filling a bin bag with toys that I didn’t like, since no one was around to stop me. I tried again. Still stuck.

Then I realised. I didn’t know how to solve the puzzle, but I did know how to write a computer program to solve it for me. That would probably be even more fun, and I could argue that it didn’t actually count as cheating. I didn’t want the solution to reveal itself to me before I’d had a chance to systematically hunt it down, so I dived across the room to turn off the console.

I wanted to have a shower but I was worried that if I did then inspiration might strike and I might figure out the answer myself. So I ran upstairs to my office, hit my Pomodoro timer, scrolled Twitter to warm up my brain, took a break, made a JIRA board, Slacked my wife a status update, no reply, she must be out of signal. Finally I fired up my preferred assistive professional tool. Time to have a real vacation.

How I wrote a Cocoon solver

In order to write a Cocoon solver, I needed to:

- Model the game’s logic using a Finite State Machine

- Use this model to work out the sequence of actions that would get me from a puzzle’s start to its end

1. Model the game’s logic

Cocoon’s mechanics are simple but elegant. In the first level you find an orange orb sitting on a stand. You pick it up, obviously, and start to carry it around. You come to a gate with an orb-stand next to it. You put the orb down on the stand and the gate opens. You pick it up again and continue through the gate.

Eventually you come to a small reflecting pool with a special-looking orb-stand in the middle. There’s no obvious path forward, so you put your orange orb down on the stand. You stand next to it and press A, because that’s the only button in the game that does anything. You watch yourself dive into the orb, and land in another world. You’re now inside the orange orb. You start to walk, You find a new, green orb, which you use to keep solving puzzles and opening doors and moving forwards through the orange orb-world. Throughout the course of the game you find a total of four orbs, and the final puzzles require you to lug them all around and dive in and out of them in just the right order to get across the next bridge.

An example: in one puzzle you need to bring your red orb to the top of a vine so that you can use it to reveal a magic walkway to get to the next area. However, you can only climb up vines while holding your green orb, and you can only hold one orb at a time. This means that you can’t carry the red orb up the vine. The solution is therefore to pick up the red orb, dive inside the green orb, drop the red orb, jump out, use the green orb to climb the vine, dive back inside the green orb, retrieve the red orb, and jump back out.

In order for my solver to analyse Cocoon, it would need to be able to programatically manipulate a copy of it. My solver would need to know how the world was laid out, what actions were allowed, and whether it had finished solving its puzzle yet. The easiest way to do this wasn’t to have the solver interact with the real game, but to instead write a new, stripped-back copy of it that contained all its logic but none of the graphics.

This was made easier by the fact that each of the puzzles that I got stuck on could be represented as a finite state machine. A finite state machine is a system that can be in exactly one of a finite number of states at any given time. The system is able to transition between some pairs of states using a set of known rules.

Most games with a large 3-D world can’t be modelled as a FSM because they have too many possible states and too many possible transitions. The player can be in a near-infinite number of slightly different locations; so can their enemies. The player might have a huge number of items they could be carrying and past actions they could have taken, each of which could affect the world in some important way. Some parts of the game may depend on timing and agility, which are hard to represent in a FSM. In most game levels there’s too much going on for a simple model like an FSM.

However, Cocoon’s is a simple world. There are no enemies. The only items you can carry are 4 orbs. And whilst its 3-D landscape is lovely to look at, it masks a simple topology that can be modelled as a small graph - a collection of nodes (important locations like orbs and switches) and edges (pathways that connect nodes that are immediately accessible from each other). Beyond these characteristics, the exact layout of the world rarely matters.

This means that a “state” in Cocoon is easy to define and manage. A state is defined by the combination of:

- The node you’re nearest

- Which orb you’re holding

- Where the other orbs are

- (possibly a few other things, depending on the exact puzzle)

Transitions between states are similarly constrained. Players can transition between game states via only a small set of actions, such as:

- Walking to an adjacent node

- Picking up or putting down an orb

- Jumping in or out of an orb

This means that it’s relatively simple to write a program that:

- Defines the layout of a puzzle world

- Defines the state that the game is currently in

- Is able to transition between states

- Knows how to identify a goal state

Once I’d written this program, I had a representation of the game that I could programmatically manipulate. I could tell my game to do things like “take such-and-such an action” or “tell me all the possible next actions that can be taken from the current state.” This meant that I could use my simplified game to analyse and solve the real one.

2. Work out how to get from the start to the goal state

To solve a puzzle I needed to find a sequence of actions that would take me from the puzzle’s start state to its goal state (for example, opening a door). This was a job for an algorithm called Breadth-First Search (BFS).

BFS starts at an initial state in an FSM and simultaneously takes a step to every new state that can be reached from it. For example, suppose that a puzzle starts with bee guy holding the green orb, next to a door and to a corridor to another section.

My solver takes steps both through the door and down the corridor, and begins keeping track of each path. From each of these new states, it takes another step to each further state that can be reached from them.

It keeps stepping and tracking the expanding number of paths that it’s exploring, until one of its paths reaches a goal state (for example, a state in which a particular orb is on a particular stand, which opens a bridge to the next area). At this point the solver stops, and returns the path that led to the goal state. Because the solver takes a single step down every possible path at once, the first path to the goal state that it finds is guaranteed to be the shortest one possible.

I can then input the sequence of actions that my solver returned into the real game (for example: pick up red orb, walk to orb holder, put down red orb, etc), and move on to the next level, without having to do any thinking whatsoever. Here’s my code.

How hard are these puzzles really?

My solver stops as soon as it has reached the goal state. However, I was also interested in fully mapping out every possible sequence of actions one could take inside a puzzle. I wanted to see how big and hard the puzzles actually are.

To do this I wrote a script that explores every possible state and transition. It keeps stepping through states transitions, even after one of its paths has reached a goal state. It only stops when none of the paths it’s exploring have any available actions that lead to a new state that it hasn’t seen before.

This script generates a new graph, in which each node is a state and each edge is a transition. The graph shows every single sequence of actions that you can take inside the puzzle. For example, here’s the puzzle that I found hardest, represented as a graph of states and transitions:

Drawing a fully-expanded FSM graph like this shows how small and simple Cocoon’s puzzles really are once you write them down. That path on the right, between the green and red nodes, requires you to put one orb inside another orb, then inside another orb, and then shuffle them around just-so. This is a counter-intuitive strategy and hard to find if you’re playing the game like a normal person.

However, writing everything down makes it obvious. Writing everything down makes all actions visible and strips away all of the misleading heuristics that make humans focus on some strategies and completely miss others. It reduces a puzzle to “find a path from the green dot to one of the red dots,” as you saw above, which can be solved by a moderately gifted two year-old. To be very facetious, Cocoon is a fluffy layer of graphics and game mechanics on top of an unbelievably simple maze.

This isn’t meant as a knock on the game. Cocoon is a tidy mind-bender that wasn’t designed to withstand exhaustive search. If you write a program to solve your Cocoon puzzles for you then you’re only cheating yourself. Or at least, you would be if writing such a program wasn’t so much fun.

Life lessons

Real life isn’t a finite state machine though. All my solver really proves is that small, low-dimensional problems can easily be solved using exhaustive search. By contrast, the world has an infinite number of states. It’s hard to be sure which properties are important, and the allowed transitions between states are terribly defined. No problem of any importance can be reduced to a tiny graph, which means that even the most determined two year-old won’t be able to help with any of the big challenges in your life.

However, you don’t need to fully explore all possible solutions in order to benefit from systematic search. As I’d feared, the process of writing my solver forced me to consider the game with so much rigour that I’d solved all 3 challenges that I used it for before I’d finished programming them in. When I came to encode every location and transition on the map in my program I was forced to pay attention to each of them individually for at least a few seconds, even the ones that the game had tricked me into ignoring. This helped me see that some of the nodes and actions that I’d thought were irrelevant were actually the key to the whole thing.

That evening I talked to my family on the phone. I showed them all the diagrams I’d created and all the fun I’d had. They showed me pictures of them inside St. Peter’s Basilica. My son asked if I’d beaten my game. I explained that I’d transcended it by creating a mathematical representation of its entire possibility space. He asked if that meant “no.”

Here’s the code to my solver, but you should really just play the game properly.