Cookie Syncing: how online trackers talk about you behind your back

21 Nov 2017

As you journey around the internet, your data and activity is sprayed into a spectacular and discomforting number of tracking companies. Your clicks pass through tools with names like retargeters, demand-side platforms, supply-side platforms, ad exchanges, audience matchers, data management platforms, data marketplaces, data onboarders, device graphs, and of course, crammed into a tiny corner, the actual website that you believe you are visiting and interacting with.

There are thousands of companies tracking you on different parts of the internet, and they each know different things about you, what you’ve done, and what you’re into. The more complete a picture they can build up of you, the more they can charge advertisers for said picture. It is therefore very often in their interests to broaden and enrich their databases by sharing and buying data about users they have seen. However, this can be challenging. Each tracker tags you with their own cookie, containing their own tracking ID (I’ve written in detail about the different types of tracker and how they use cookies if you need to expand or refresh your memory). A user that one tracker affectionately calls fdsxjhkfsdjhksfd might be known to a second tracker only as treyiuotreyuioert. Since browsers do not allow trackers to access each other’s cookies, by default they have no way to know the ID that the others have assigned you, no way to know when they are each talking about the same person, and no way to sell each other extra data about you.

To solve their communication problems, many trackers exchange user IDs through a process known as cookie syncing, an intricate dance unwittingly played out by your browser. Once two trackers have synced your cookies, they can share details on which websites you’ve been visiting, and demographic or personal information about you can paint this into the picture too. We have no way of knowing how much data sharing actually goes on behind the scenes, but I would be more than a little surprised if it wasn’t the absolute maximum technologically and legally possible, plus a little bit extra.

This is troubling for consumers. In addition to all the normal privacy concerns surrounding tracking of any kind, it concentrates and centralizes knowledge about you and your data, and helps companies you’ve never heard of build more complete pictures of you than you would ever knowingly be comfortable with. Consumers don’t really gain anything in the trade, apart from in the indirect sense that your data is what paid for that heart-wrenching article on the opioid epidemic you just finished reading. You do theoretically get more relevant and precisely targeted ads, but it’s not at all clear to me that this is a good thing. On the other hand, if you believe ad industry literature then cookie syncing is just one of the many ways in which they are helping to fulfill your right to life, liberty, and a consistent browsing experience.

How cookies get synced

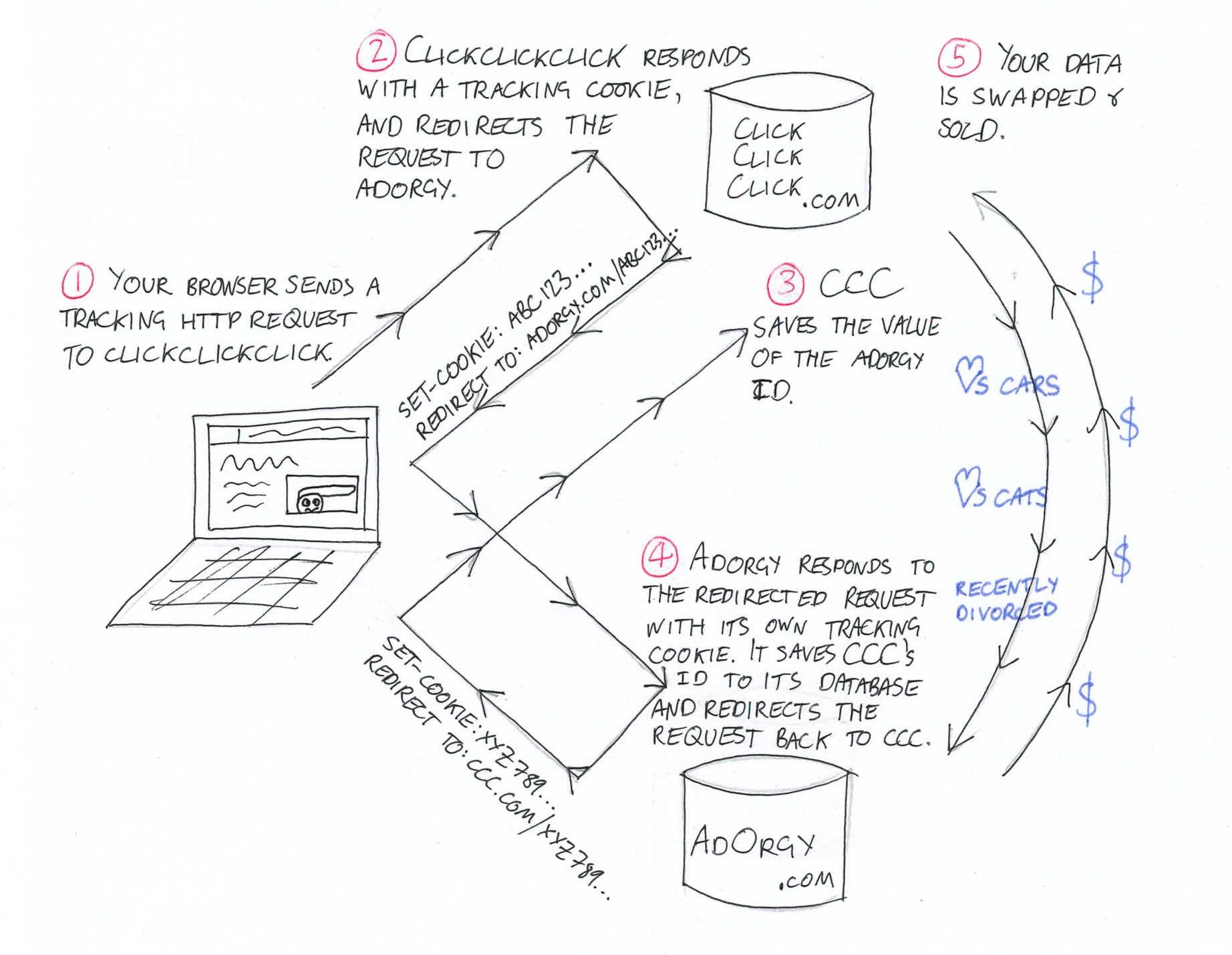

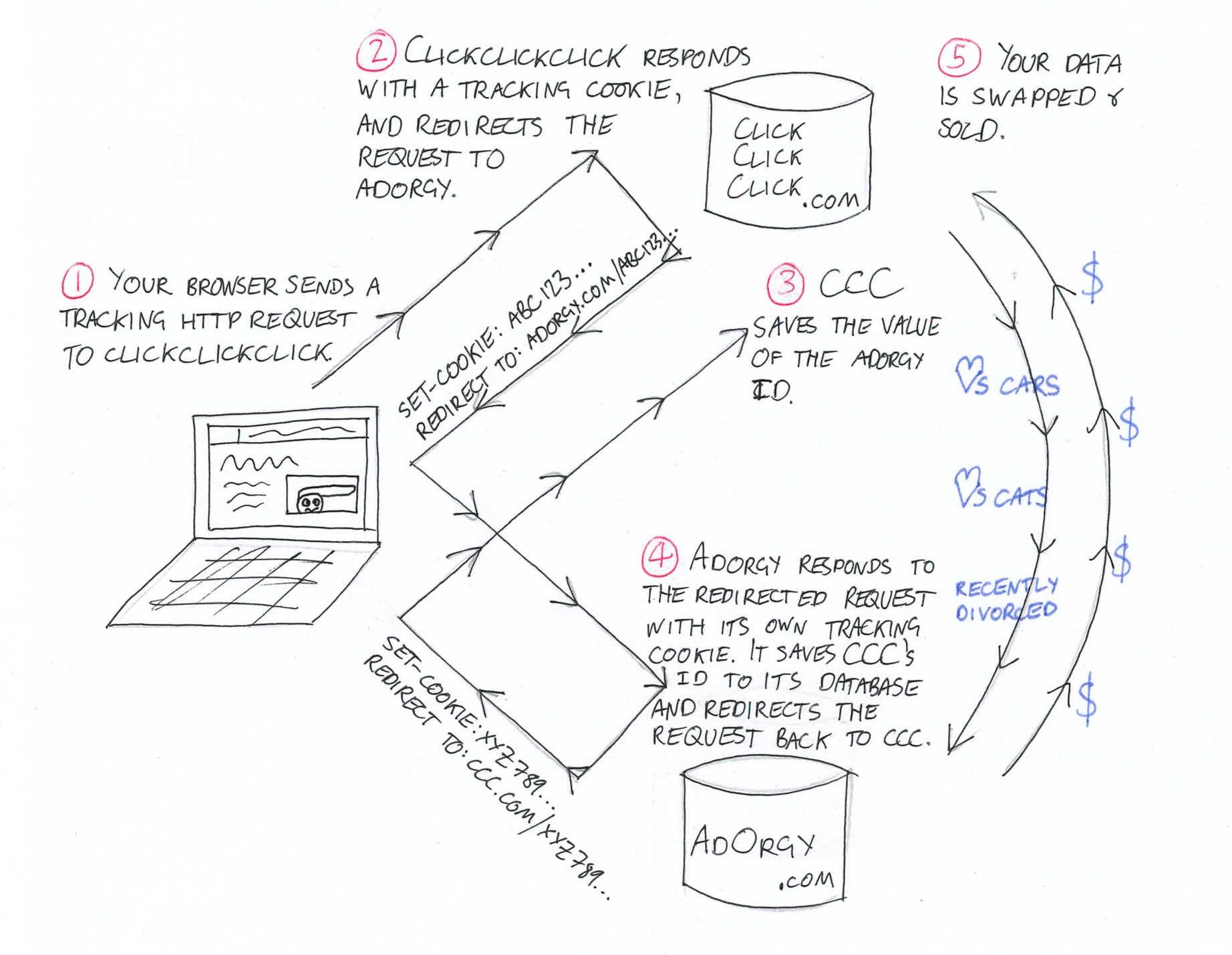

Consider the first visit you ever made to NewsFromQuestionableSources.com. Suppose that NFQS uses two third-party, multi-website trackers in order to maximize the amount of data they can get about their users. Let’s call these two trackers AdOrgy and ClickClickClick, and suppose that neither of these trackers has ever seen you before. Their shared goal is for each tracker to assign you a tracking ID, and to then send this ID to the other tracker. This allows them to link together the IDs that they have assigned you, and use this connection to exchange more information about you later.

First, ClickClickClick assigns you a tracking ID. To help do this, NewsFromQuestionableSources.com loads some of ClickClickClick’s Javascript, which instructs your browser to send an HTTP ping to ClickClickClick.com’s tracking URL. As with normal, unsynced tracking, the ClickClickClick server generates a unique ID, returns this ID to your browser, and instructs your browser to save it in a cookie.

However, this response from ClickClickClick also instructs your browser to redirect the request it just made over to AdOrgy’s cookie-syncing URL, with the ClickClickClick ID that it just generated appended to the end as a URL parameter. It does this by returning a 302 status code and a new Location header, indicating a redirect, instead of the more normal 200 status code, indicating success.

When it receives this redirected request, the AdOrgy server generates its own unique ID. Crucially, it also saves to its database the link between this ID and the ClickClickClick ID it sees in the request URL. As usual, it returns the ID to your browser and instructs it to save the ID in another cookie. To complete the circle, the AdOrgy response instructs your browser to redirect the request a second time, back to ClickClickClick cookie-sync URL, with the AdOrgy ID appended as a URL parameter. ClickClickClick saves the link between the two IDs, and the cookie sync is done. Both ClickClickClick and AdOrgy now know the ID that the other has assigned this user, and are free to swap data about them behind the scenes.

Here’s an example of cookie syncing in action on TheGuardian.com. I chose TheGuardian.com in order to show that cookie syncing is truly a mainstream technique, and that even venerable lefty newspapers with relatively robust subscriber bases need to maximize ad revenue.

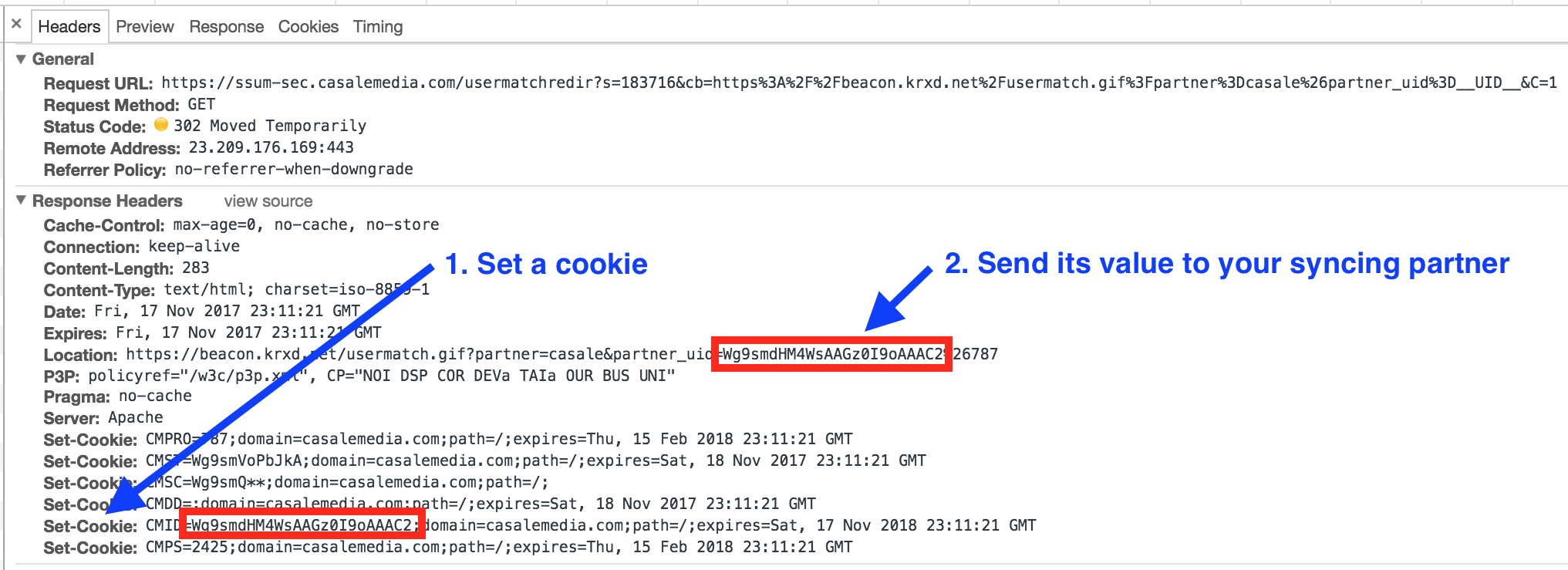

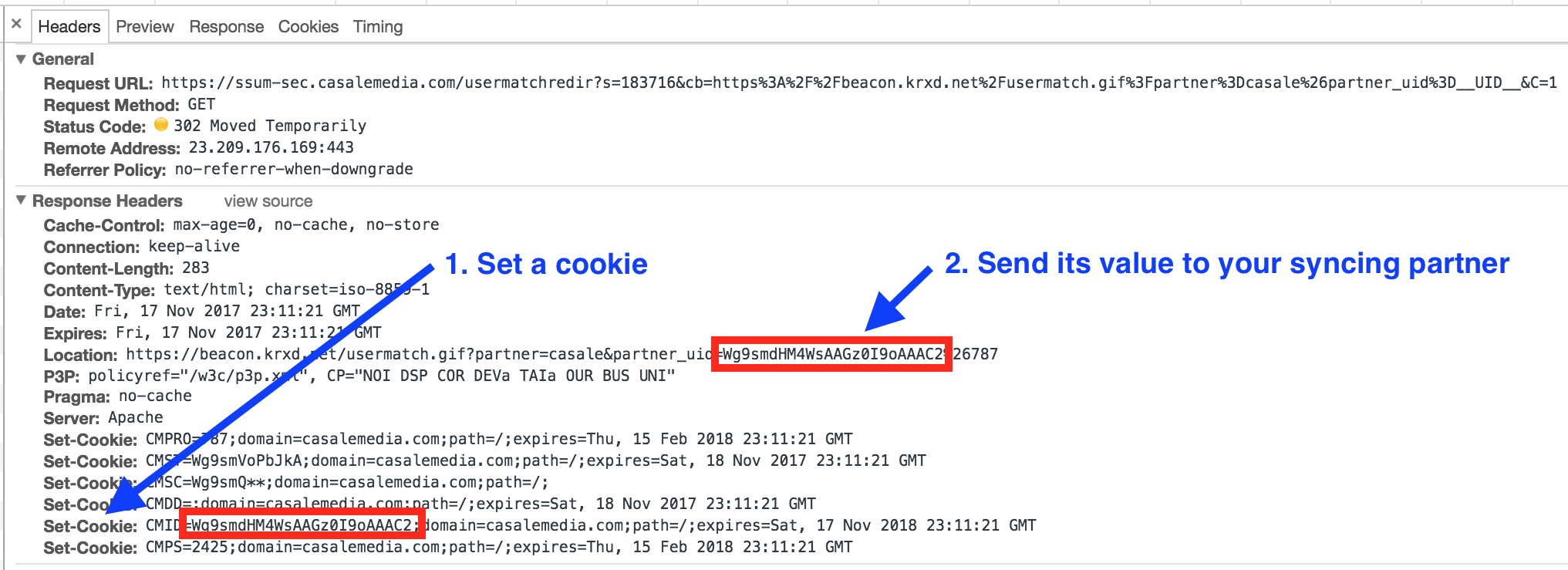

When I visit TheGuardian.com in search of a thoughtful hot take, the first request in the cookie syncing samba is sent to CasaleMedia (ssum-sec.casalemedia.com), a tracker of some sort. CasaleMedia responds to this request with several cookies (the important one containing my new tracking ID has the value Wg9smdHM4WsAAGz0I9oAAAC2), and redirects the request to another tracker called KRXD (beacon.krxd.net). The KRXD URL has my CasaleMedia tracking ID clearly attached to the end. KRXD now know what ID CasaleMedia have assigned me.

The redirected request to KRXD does not actually get re-redirected back to CasaleMedia. This means that KRXD know the ID that CasaleMedia have assigned me, but not vice versa. This could be a deliberate feature of their business agreement; it is also possible that KRXD send the ID that they have assigned me over to CasaleMedia elsewhere in the page load.

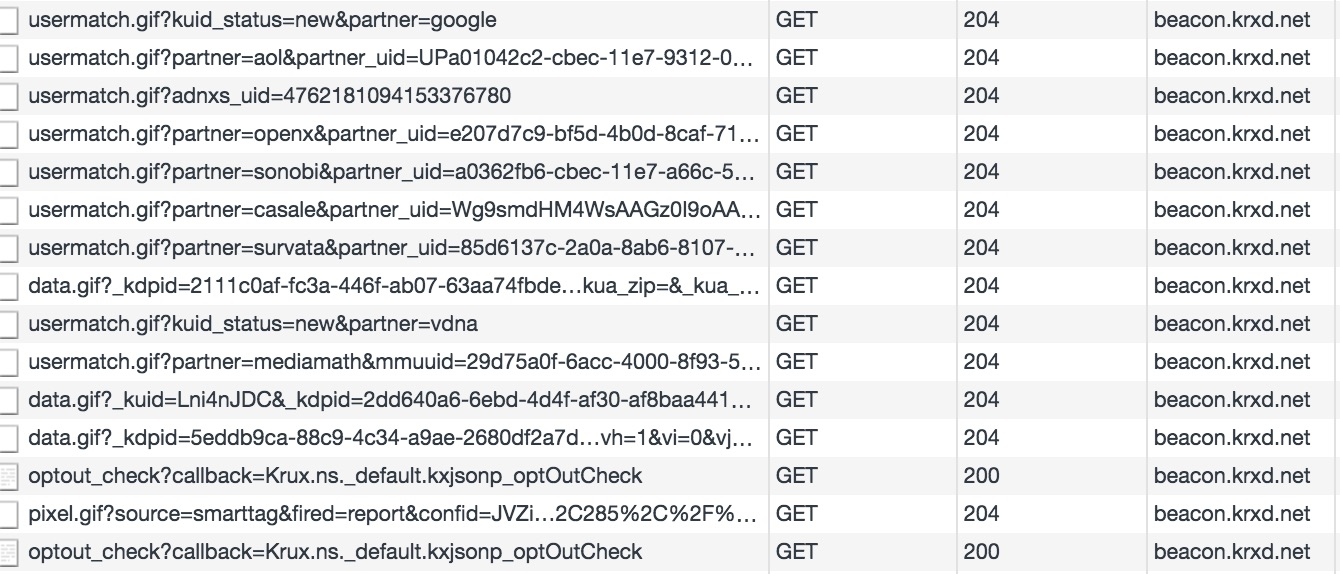

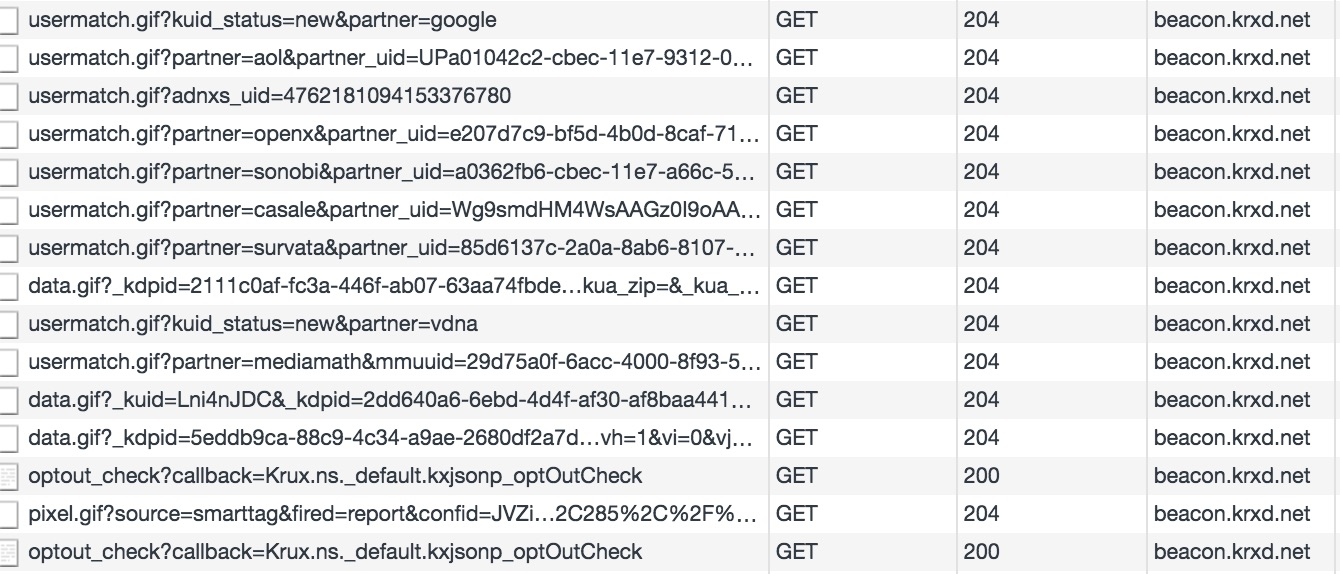

In addition to CasaleMedia, KRXD attempt to sync cookies with no fewer than 8 other tracking companies whenever anyone loads TheGuardian.com. They may be syncing with other behavior trackers in order to expand their reach. They may be syncing with ad networks in order to allow their advertisers to make more informed bids. They may be syncing cookies with “identity graphs”, companies whose entire reason for existence is trying to figure out which phones and computers are owned by the same person. Or perhaps KRXD are the ones with a valuable tracking product that these other 10 companies want to buy. We have no way of knowing what goes on once cookies are synced. Cookie syncing is cheap and easy, and the market for data is big business.

Defence against the dark ads

All this is arguably my fault for not taking out a subscription to The Guardian despite their nice requests at the bottom of every article. Every website has to get paid somehow, and if we’re the product then they’ve got to paint as detailed and appetizing picture of us as they can to their advertisers. Anything less is leaving money on an already shrinking table. However, this doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t defend against this kind of tracking whilst deciding how else to fulfill any obligations you may feel towards online publishers. Commonly suggested tactics include getting an ad blocker, using Tor or using Brave. You could also wait and see how the the EU’s new data control legislation (the GDPR) shakes out when it comes into effect in 2018 and then move to France. Whatever it is, you should do something - the number of companies who talk about you behind your back is not going down.

As you journey around the internet, your data and activity is sprayed into a spectacular and discomforting number of tracking companies. Your clicks pass through tools with names like retargeters, demand-side platforms, supply-side platforms, ad exchanges, audience matchers, data management platforms, data marketplaces, data onboarders, device graphs, and of course, crammed into a tiny corner, the actual website that you believe you are visiting and interacting with.

There are thousands of companies tracking you on different parts of the internet, and they each know different things about you, what you’ve done, and what you’re into. The more complete a picture they can build up of you, the more they can charge advertisers for said picture. It is therefore very often in their interests to broaden and enrich their databases by sharing and buying data about users they have seen. However, this can be challenging. Each tracker tags you with their own cookie, containing their own tracking ID (I’ve written in detail about the different types of tracker and how they use cookies if you need to expand or refresh your memory). A user that one tracker affectionately calls fdsxjhkfsdjhksfd might be known to a second tracker only as treyiuotreyuioert. Since browsers do not allow trackers to access each other’s cookies, by default they have no way to know the ID that the others have assigned you, no way to know when they are each talking about the same person, and no way to sell each other extra data about you.

To solve their communication problems, many trackers exchange user IDs through a process known as cookie syncing, an intricate dance unwittingly played out by your browser. Once two trackers have synced your cookies, they can share details on which websites you’ve been visiting, and demographic or personal information about you can paint this into the picture too. We have no way of knowing how much data sharing actually goes on behind the scenes, but I would be more than a little surprised if it wasn’t the absolute maximum technologically and legally possible, plus a little bit extra.

This is troubling for consumers. In addition to all the normal privacy concerns surrounding tracking of any kind, it concentrates and centralizes knowledge about you and your data, and helps companies you’ve never heard of build more complete pictures of you than you would ever knowingly be comfortable with. Consumers don’t really gain anything in the trade, apart from in the indirect sense that your data is what paid for that heart-wrenching article on the opioid epidemic you just finished reading. You do theoretically get more relevant and precisely targeted ads, but it’s not at all clear to me that this is a good thing. On the other hand, if you believe ad industry literature then cookie syncing is just one of the many ways in which they are helping to fulfill your right to life, liberty, and a consistent browsing experience.

How cookies get synced

Consider the first visit you ever made to NewsFromQuestionableSources.com. Suppose that NFQS uses two third-party, multi-website trackers in order to maximize the amount of data they can get about their users. Let’s call these two trackers AdOrgy and ClickClickClick, and suppose that neither of these trackers has ever seen you before. Their shared goal is for each tracker to assign you a tracking ID, and to then send this ID to the other tracker. This allows them to link together the IDs that they have assigned you, and use this connection to exchange more information about you later.

First, ClickClickClick assigns you a tracking ID. To help do this, NewsFromQuestionableSources.com loads some of ClickClickClick’s Javascript, which instructs your browser to send an HTTP ping to ClickClickClick.com’s tracking URL. As with normal, unsynced tracking, the ClickClickClick server generates a unique ID, returns this ID to your browser, and instructs your browser to save it in a cookie.

However, this response from ClickClickClick also instructs your browser to redirect the request it just made over to AdOrgy’s cookie-syncing URL, with the ClickClickClick ID that it just generated appended to the end as a URL parameter. It does this by returning a 302 status code and a new Location header, indicating a redirect, instead of the more normal 200 status code, indicating success.

When it receives this redirected request, the AdOrgy server generates its own unique ID. Crucially, it also saves to its database the link between this ID and the ClickClickClick ID it sees in the request URL. As usual, it returns the ID to your browser and instructs it to save the ID in another cookie. To complete the circle, the AdOrgy response instructs your browser to redirect the request a second time, back to ClickClickClick cookie-sync URL, with the AdOrgy ID appended as a URL parameter. ClickClickClick saves the link between the two IDs, and the cookie sync is done. Both ClickClickClick and AdOrgy now know the ID that the other has assigned this user, and are free to swap data about them behind the scenes.

Here’s an example of cookie syncing in action on TheGuardian.com. I chose TheGuardian.com in order to show that cookie syncing is truly a mainstream technique, and that even venerable lefty newspapers with relatively robust subscriber bases need to maximize ad revenue.

When I visit TheGuardian.com in search of a thoughtful hot take, the first request in the cookie syncing samba is sent to CasaleMedia (ssum-sec.casalemedia.com), a tracker of some sort. CasaleMedia responds to this request with several cookies (the important one containing my new tracking ID has the value Wg9smdHM4WsAAGz0I9oAAAC2), and redirects the request to another tracker called KRXD (beacon.krxd.net). The KRXD URL has my CasaleMedia tracking ID clearly attached to the end. KRXD now know what ID CasaleMedia have assigned me.

The redirected request to KRXD does not actually get re-redirected back to CasaleMedia. This means that KRXD know the ID that CasaleMedia have assigned me, but not vice versa. This could be a deliberate feature of their business agreement; it is also possible that KRXD send the ID that they have assigned me over to CasaleMedia elsewhere in the page load.

In addition to CasaleMedia, KRXD attempt to sync cookies with no fewer than 8 other tracking companies whenever anyone loads TheGuardian.com. They may be syncing with other behavior trackers in order to expand their reach. They may be syncing with ad networks in order to allow their advertisers to make more informed bids. They may be syncing cookies with “identity graphs”, companies whose entire reason for existence is trying to figure out which phones and computers are owned by the same person. Or perhaps KRXD are the ones with a valuable tracking product that these other 10 companies want to buy. We have no way of knowing what goes on once cookies are synced. Cookie syncing is cheap and easy, and the market for data is big business.

Defence against the dark ads

All this is arguably my fault for not taking out a subscription to The Guardian despite their nice requests at the bottom of every article. Every website has to get paid somehow, and if we’re the product then they’ve got to paint as detailed and appetizing picture of us as they can to their advertisers. Anything less is leaving money on an already shrinking table. However, this doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t defend against this kind of tracking whilst deciding how else to fulfill any obligations you may feel towards online publishers. Commonly suggested tactics include getting an ad blocker, using Tor or using Brave. You could also wait and see how the the EU’s new data control legislation (the GDPR) shakes out when it comes into effect in 2018 and then move to France. Whatever it is, you should do something - the number of companies who talk about you behind your back is not going down.