Identity Graphs: how online trackers follow you across devices

24 Nov 2017

You are in a grimy, pungent bar with your good friend, Wendy Wrigglesworth. It is the perfect place to explain your idea for a killer prank on your worse and more annoying friend, Steve Steveington. You’ve been hearing a lot about tools that online advertisers use to link together your behavior across your phone, laptop, work laptop, Xbox and work Xbox. The ad industry calls them “identity graphs”. You think that you and Wendy should create your own identity graph, use it to link together Steve Steveington’s devices, and then show him a carefully targeted series of ads across all his devices. Your plan gets a bit more vague and hard to follow after that, but it sounds like the Stevester ends up spending his upcoming birthday try to navigate a Kafka-esque maze of traumatizing fake birthday parties before he is finally allowed to see his family for a short, awkward dinner.

Besides taking issue with some of the details of the otherwise very amusing prank, Wendy patiently explains to you that building an identity graph is actually very hard. You’d need at least a few million dollars in seed funding, as well as clients and partners who could provide clean and consistent first-, second- and third-party data. You’d need scores of data scientists to build models, scores of scores of terabytes of storage space, and an unpaid intern to do devops. Sure you could save a bit of time and money by refusing to do a 401k match and focussing on a self-service product that didn’t require a large enterprise sales team, but you’d still have to build a successful online advertising company and make billions of dollars, just to prank your stupid friend. Would it really be worth it?

You ask whether you could just use an existing company’s identity graph to track and follow Steve Steveington. Probably not, says Wendy. Even though the online advertising industry does kind of look like a hive of villainy and questionable practices, ad companies won’t just tell you precisely what unholy turpitude Steve Steveington has been up to recently (although if you give them his email address then they’ll try to find him and show him your ads). Whilst online advertisers and trackers do collect a huge amount of data about internet users, there is probably a strict set of self-regulatory non-binding guidelines discouraging them from abusing it, and these are probably categorically, unquestionably a bit better than nothing. The ad industry really doesn’t care who you are, they just want to figure out what you’ll click on. She makes it clear that she is still wholly on board with the whole pranking Steve Steveington concept though. She’s been setting him up for a doozie that might be the one to finally break him.

Disappointed but not defeated, you email Wendy Wrigglesworth a few links about identity graphs when you get home. You don’t see Wendy for a few weeks. When you finally catch up with her at ping-pong practice her eyes are red and her movement is sluggish. She misses some trivial backhands, but still beats you handily. After the match she explains that whilst she originally only started reading the links you sent in order to make fun of you later, she found that once she started reading she couldn’t stop. Her eyes wide, she tells you everything she now knows about identity graphs.

Wendy’s introduction to Identity Graphs

As I think I’ve told you before (Wendy says), I live in a one-bed in the last real neighborhood in New York. I’m not going to tell you where this neighborhood in case you come and gentrify it. Whilst I was moving in I heard my neighbors shouting their wi-fi password across their apartment, so now I just borrow their internet instead of paying for my own. My apartment is cheap, huge and extremely tastefully decorated, and so over the years several guys I’ve had the misfortune of dating have invited themselves to move in with me. I usually charge them for half of next-door’s internet connection. Those darn cable companies, always putting up the rates. It’s not the most ethical side of my life, but they usually turn out to be deadbeat wastrels who don’t end up paying for anything, so I don’t feel too bad.

It seems that most identity graphs use IP address and location data to link devices together. Devices that appear in the same place, on the same wi-fi network, probably belong to the same person. You might therefore think that an identity graph would find my apartment confusing. How is it meant to know which phone in the apartment is mine and which is Mike, Sanjit, Tom or other Sanjit’s? If the identity graph can’t figure this out then Mike will get shown ads for ping-pong bats and I’ll get shown ads for stupid goddamn bullshit. But distinguishing between people who live in the same place is not so hard given enough data. Perhaps they notice that my phone tends to connect to the same coffee shop wifi as my laptop. Perhaps they also notice that Tom’s tablet and his other tablet (who has two tablets? Christ he was an idiot) both take trips to the West Coast at the same time. And then maybe there’s this other mystery device. They don’t have enough location data to know exactly who it belongs to, but they do notice that it spends a lot of time looking at ping-pong websites and zero time looking at websites about stupid goddamn bullshit. There’s a nearby cluster of devices that seem to belong to someone with much the same interests. They add the device into this cluster and consider the mystery solved.

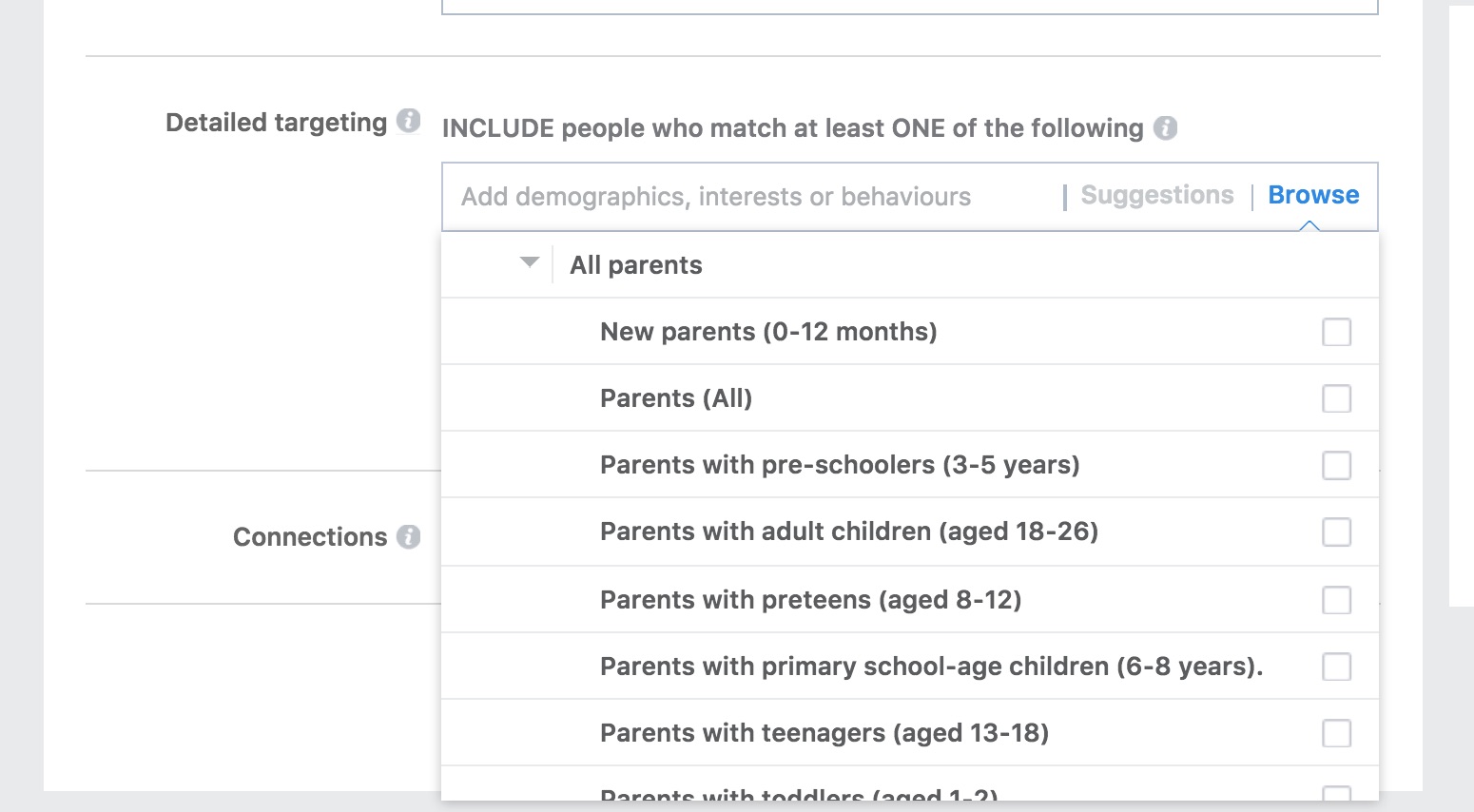

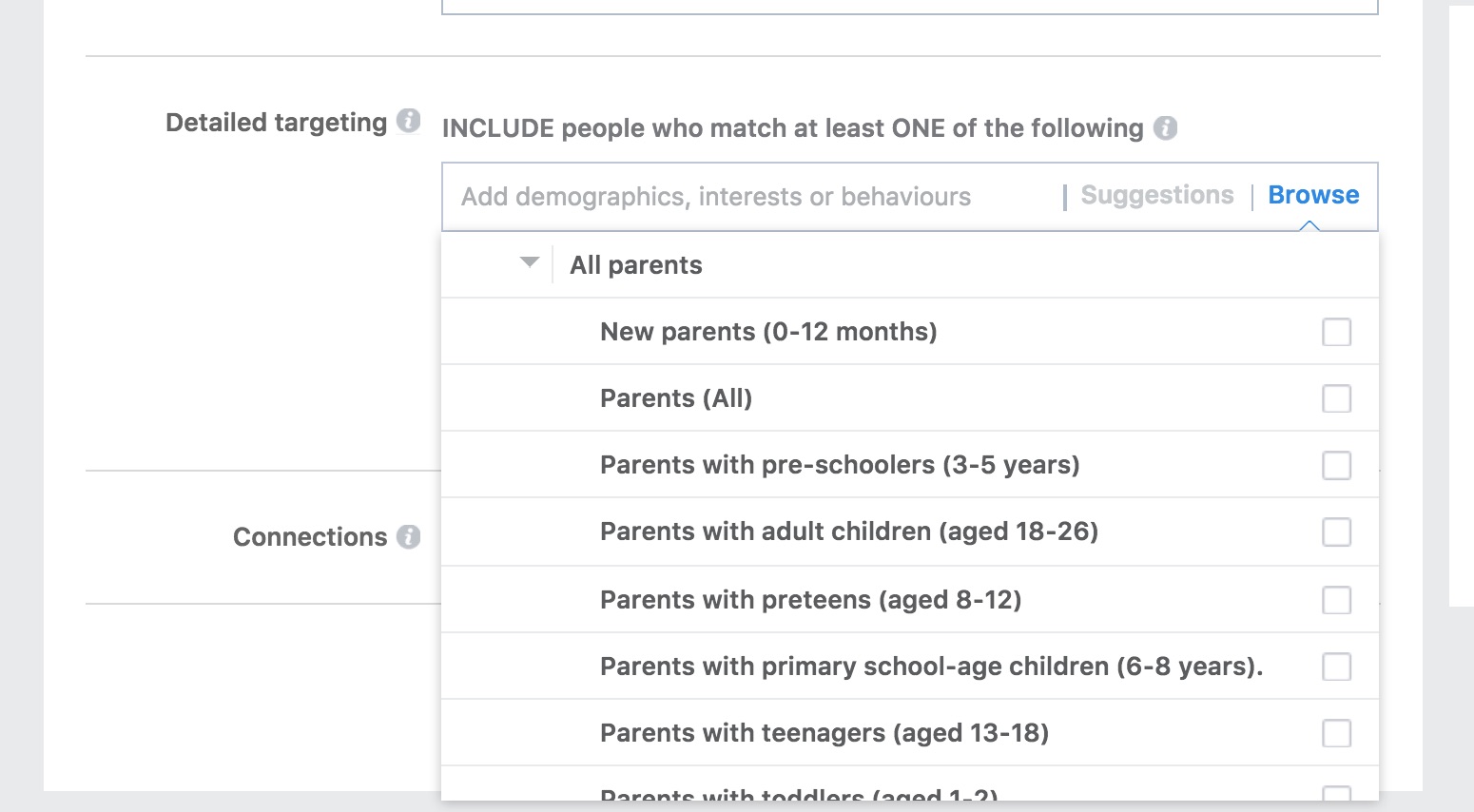

Once an identity graph has correctly partitioned a tricky thicket of devices belonging to multiple people, they’ve also created several new dimensions of information. Not only have they grouped together all my devices, but they’ve also figured out where I spend a lot of my time and which other groups of devices and therefore people I spend it with. I can’t even imagine the advertising segments Facebook could generate using this data. “Young adult who has just left home.” “Parents of children who have all left home.” “Recent divorcee who doesn’t seem to want to talk about it.” As far as I can tell, they don’t use their identity graph in this way. I have no idea why not.

Why do advertisers need Identity Graphs?

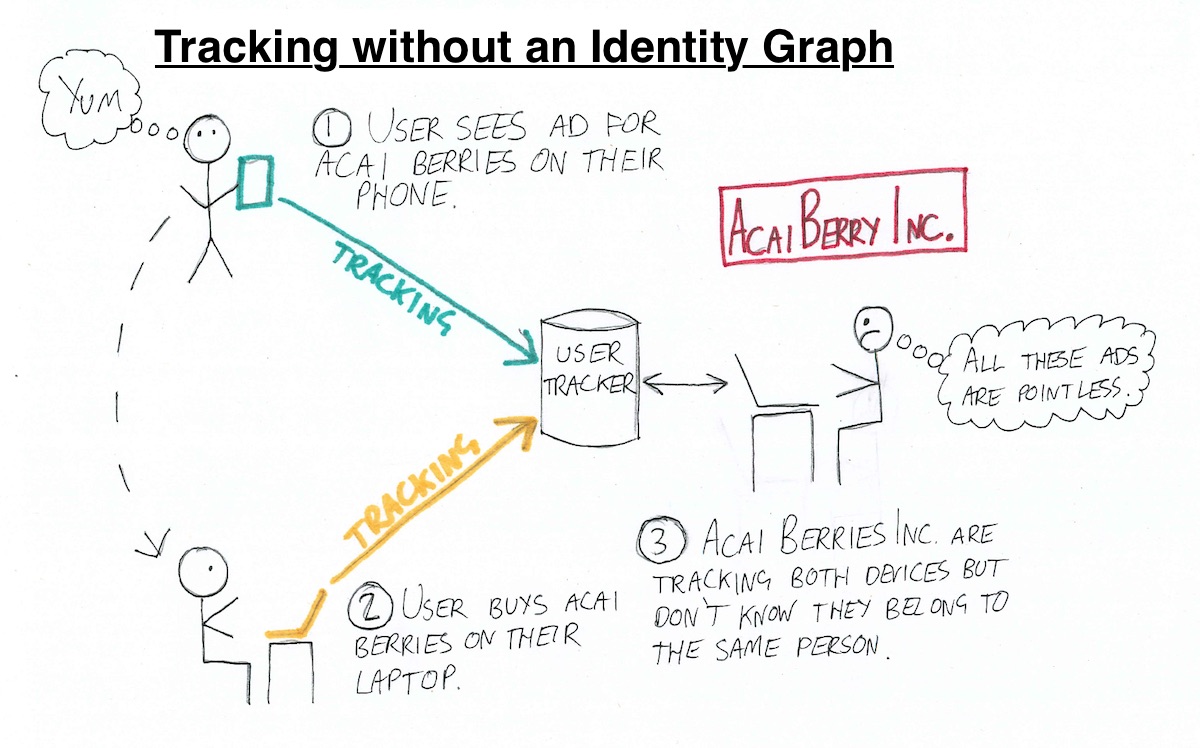

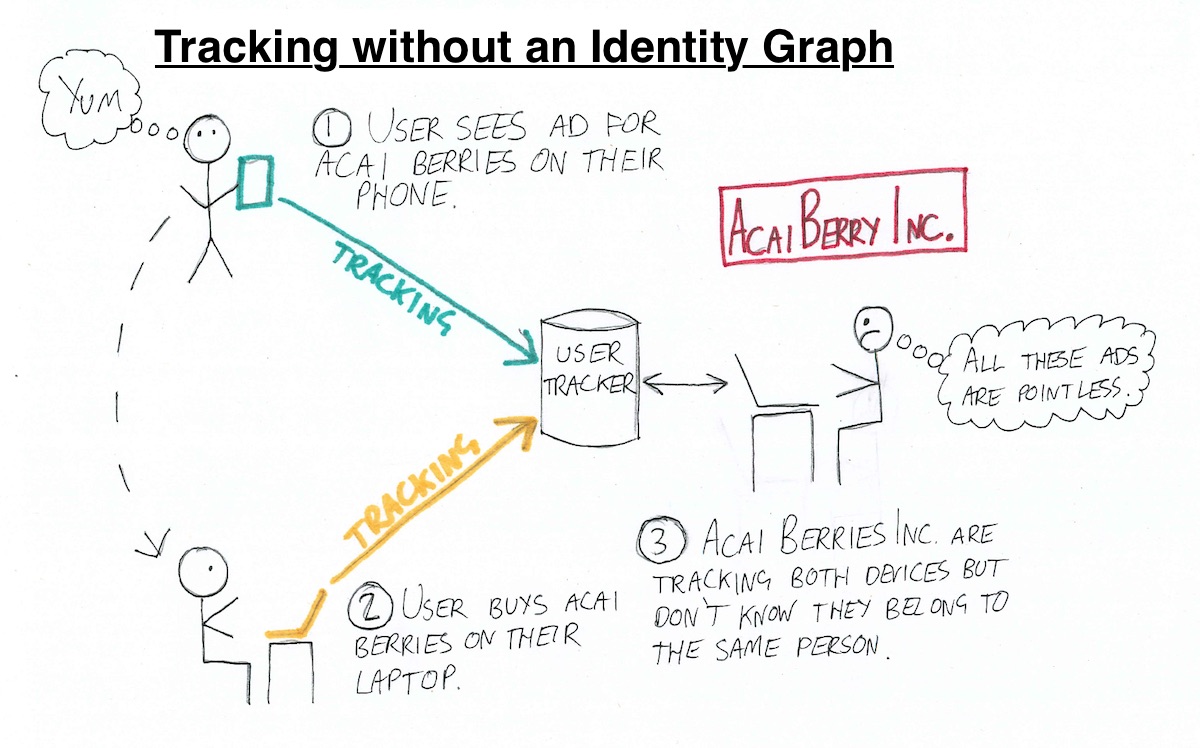

Today’s multi-screen consumer will often see an ad for a product on one device, do further research on another, and actually buy the product on yet another. This makes it hard for advertisers to know that their original ad was what caused the eventual purchase. It’s hard for them to know if they are any good at their jobs, and this leads to a huge amount of existential angst in the online marketing community.

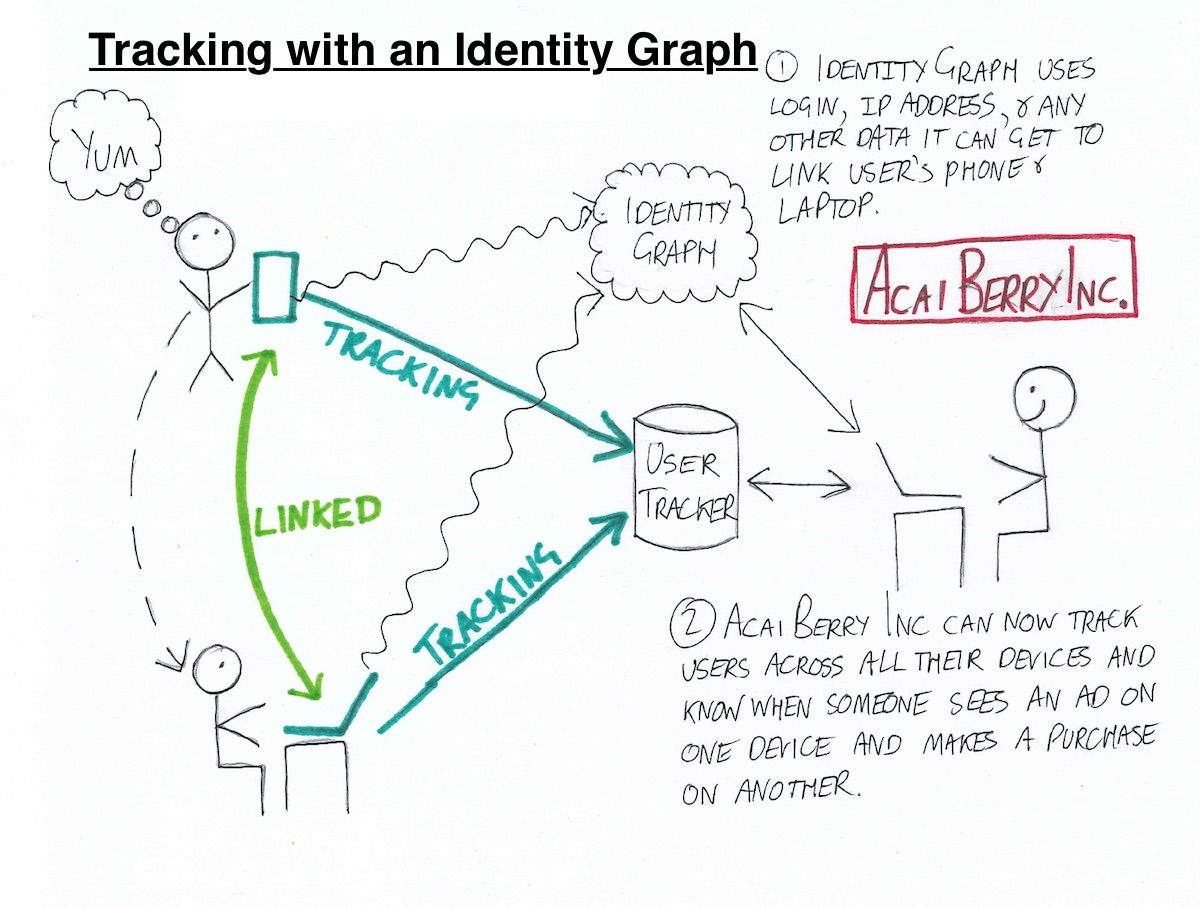

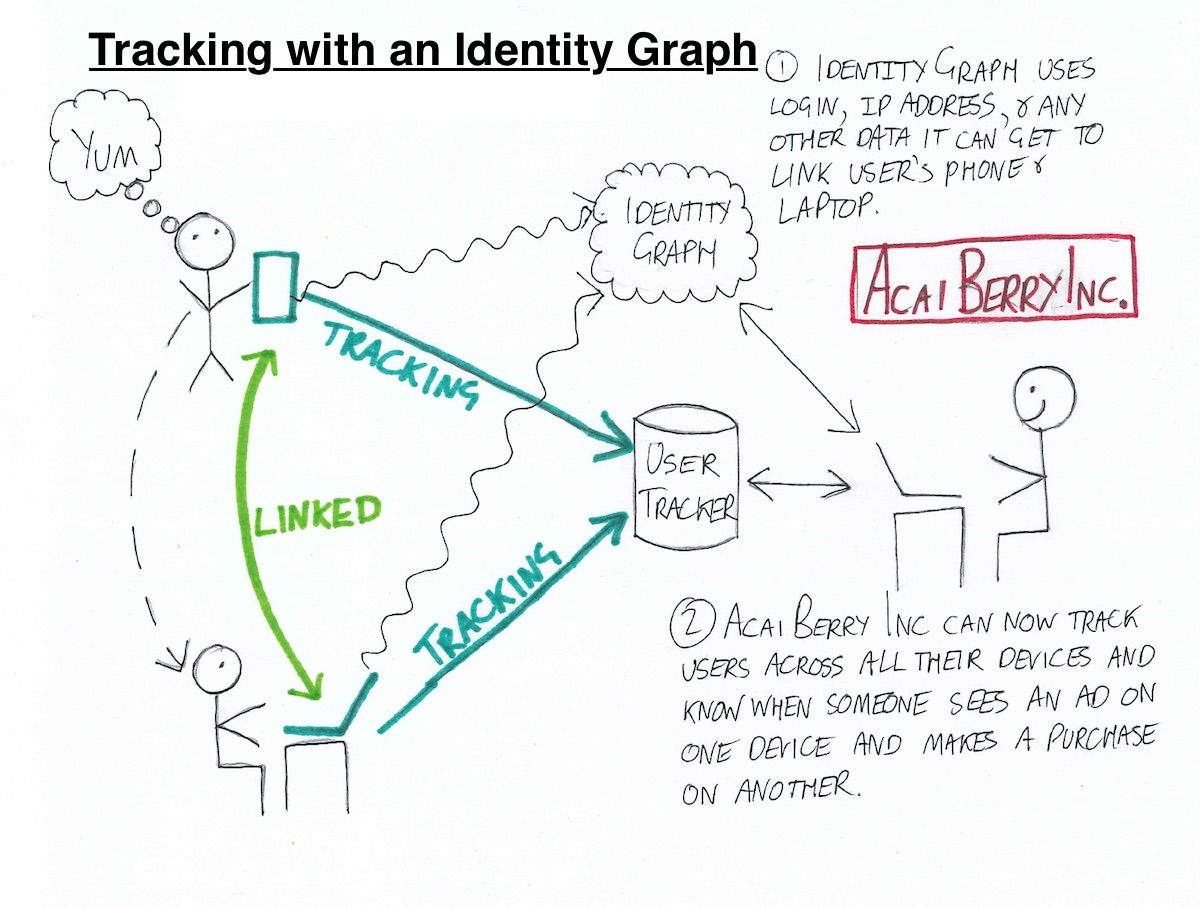

To solve this problem, tracking companies build identity graphs. An identity graph consists of a web of devices and ownership links between them. Advertisers can use an identity graph to see that the user who just bought some acai berries on their laptop had previously seen five banner ads for them on their phone and tablet.

Vanilla single-device online trackers assign your device a persistent ID, store it on your device (usually in a cookie) and use it to track your behavior. I read a really good summary of how they work pitched at just the right level of technical detail, I’ll send you the link. By contrast, whilst multi-device trackers start by assigning and tracking IDs in the same way, they add an additional layer of intelligence to attempt to link together IDs of devices that belong to the same person.

Assigning IDs to your devices

Ad industry literature, like this 2015 white paper by AdBrain, describes two classes of tracking ID - deterministic and statistical. A deterministic ID is one that is explicitly assigned to and stored on a device. The most common types of deterministic identifier are Apple’s Identifier for Advertising (IDFA), Android’s Advertiser ID (AAID), and IDs generated by trackers and stored in cookies. These IDs are appended to requests sent to the tracker and allow them to identify a user with near certainty.

A statistical ID appears to be a euphemism for a device fingerprint, as AdBrain note on pWHATEVER of their white paper. Devices and browsers have a vast array of different settings and options; so many that the exact configuration on your device is very often unique to you. It’s as though you are the only person at your favorite fast-food chain who ever orders a vegan McMushroom burger with a side of kale and half a battery-farmed chicken. The fast-food chain could use your unique food order to follow your movements around the city and country, without even needing to use the tracking beacons they hide inside your…I’ve said too much. Anyway, online trackers can often access many of your device’s settings and turn them into a fingerprint that uniquely identifies you. They can identify and track you without having to store an identifier on your device. This means that there is nothing for you to delete, and no way to know if you are being tracked short of inspecting the requests coming out of your device, or just assuming that you are.

There are many ways an identity graph creator can tag a device with an ID. They can piggy-back off their existing service as a third-party tracker, sync their cookies with other trackers and share their data, or even sync their cookies with first-party websites that users have explicitly logged into.

Connecting your devices to each other

Once an identity graph creator has assigned IDs to devices, they build on this with a combination of ingenuity, purchased data and metadata leakage to connect together IDs and devices belonging to the same person.

The easiest and most reliable way for an identity graph to connect two devices is if it knows that the same person has explicitly logged in to an account of some kind on both devices. Facebook knows that all of your Facebook-enabled devices belong to you because you told them that they did. However, very few products have first-party data that covers a worthwhile fraction of internet users. Those that do typically aren’t sharing unless you buy ads on their platform.

Identity graph creators who don’t own a vast silo of first-party login data have to work harder. From reading ad industry blogs, it seems that the most common way that identity graphs connect devices is by looking at their IP address and therefore approximate location throughout the day. A phone and laptop that spend the evenings together in one location are probably a person’s personal devices. A second laptop that appears with the phone during the weekdays is probably their work computer. And that tablet that is also on their home network but only ever goes online past midnight is probably theirs too and we should just collect whatever data we can without asking too many probing questions.

Identity graph providers can further expand their reach by combining data they collect themselves with similar data held by second- and third-party sources, including other trackers. This can be vital, since they can only directly collect data for users of websites that use their tracking software. But if two trackers have databases of user behavior that contain user email addresses (which can come from all manner of different sources), then they can directly combine their databases by matching users by their email address (usually in a hashed, obfuscated form). They can combine databases of mobile behavior by comparing mobile advertising IDs (like IDFA and AAID). And they can even combine databases containing no personally identifiable information at all using cookie syncing.

Conclusion

There’s a concept in encryption called perfect forward secrecy. This is a property of some encryption protocols that keeps past communication secret, even if their private keys are compromised. I think of the modern internet as having perfect forward vulnerability - once your information gets out, there’s no way to make it private again. This is less of a problem when many little companies know a little bit about us, but as ever-bigger and more powerful trackers start to join the dots between our activity on more websites and devices, they begin to build up a distressingly detailed picture of us and our habits. This might be acceptable if we had more knowledge and control over what this data is used for. And I don’t know about you, but I sure don’t feel in control right now.

I did some pretty weird stuff on the internet back in the day. With hindsight I’m pretty sure that the other people on the forum were not actually seventeen and that those roubles did not come from a chain of hardware stores for the elderly. It wasn’t illegal as such, but it was certainly against the eBay terms of service and the scriptures of most (but interestingly not all) major religions.

I was very careful to only ever log in on a burner phone. Whilst I’m quite sure that the FBI won’t ever catch me, I still find it disconcerting that a company whose name starts with “Ad” and ends with a random noun has probably stitched together enough data sources to connect my laptop to my phone to my old phone to my old laptop to my old old phone to… None of this requires any special technology - just collecting and connecting all the data you can sniff out or buy. Nowadays I use an adblocker, a VPN and a new email address for every service or newsletter I sign up to, but I’m not even sure what exactly it is that I want to stay private from. I guess I’m afraid that we’re on a slippery slope, with no idea where it goes, and with a long way left to the bottom.

The ping-pong hall is long empty. Well, none of that sounds good for me, the consumer, you say. What can I do about it? Same as always, replies Wendy. Adblocker, VPN, Tor, Signal or Whatsapp, and don’t do anything you wouldn’t want your mother or toothpaste company to know about. Hey - shall we still try and throw Steve a fake birthday party next week?

You nod. She turns for the door. Still clearly extremely tired and delusional from a week of not sleeping, she trips over what appears to be absolutely nothing on her way out. You turn out the lights and head for your car. You feel a strange, inexplicable desire to purchase a Ford Mustang.

You are in a grimy, pungent bar with your good friend, Wendy Wrigglesworth. It is the perfect place to explain your idea for a killer prank on your worse and more annoying friend, Steve Steveington. You’ve been hearing a lot about tools that online advertisers use to link together your behavior across your phone, laptop, work laptop, Xbox and work Xbox. The ad industry calls them “identity graphs”. You think that you and Wendy should create your own identity graph, use it to link together Steve Steveington’s devices, and then show him a carefully targeted series of ads across all his devices. Your plan gets a bit more vague and hard to follow after that, but it sounds like the Stevester ends up spending his upcoming birthday try to navigate a Kafka-esque maze of traumatizing fake birthday parties before he is finally allowed to see his family for a short, awkward dinner.

Besides taking issue with some of the details of the otherwise very amusing prank, Wendy patiently explains to you that building an identity graph is actually very hard. You’d need at least a few million dollars in seed funding, as well as clients and partners who could provide clean and consistent first-, second- and third-party data. You’d need scores of data scientists to build models, scores of scores of terabytes of storage space, and an unpaid intern to do devops. Sure you could save a bit of time and money by refusing to do a 401k match and focussing on a self-service product that didn’t require a large enterprise sales team, but you’d still have to build a successful online advertising company and make billions of dollars, just to prank your stupid friend. Would it really be worth it?

You ask whether you could just use an existing company’s identity graph to track and follow Steve Steveington. Probably not, says Wendy. Even though the online advertising industry does kind of look like a hive of villainy and questionable practices, ad companies won’t just tell you precisely what unholy turpitude Steve Steveington has been up to recently (although if you give them his email address then they’ll try to find him and show him your ads). Whilst online advertisers and trackers do collect a huge amount of data about internet users, there is probably a strict set of self-regulatory non-binding guidelines discouraging them from abusing it, and these are probably categorically, unquestionably a bit better than nothing. The ad industry really doesn’t care who you are, they just want to figure out what you’ll click on. She makes it clear that she is still wholly on board with the whole pranking Steve Steveington concept though. She’s been setting him up for a doozie that might be the one to finally break him.

Disappointed but not defeated, you email Wendy Wrigglesworth a few links about identity graphs when you get home. You don’t see Wendy for a few weeks. When you finally catch up with her at ping-pong practice her eyes are red and her movement is sluggish. She misses some trivial backhands, but still beats you handily. After the match she explains that whilst she originally only started reading the links you sent in order to make fun of you later, she found that once she started reading she couldn’t stop. Her eyes wide, she tells you everything she now knows about identity graphs.

Wendy’s introduction to Identity Graphs

As I think I’ve told you before (Wendy says), I live in a one-bed in the last real neighborhood in New York. I’m not going to tell you where this neighborhood in case you come and gentrify it. Whilst I was moving in I heard my neighbors shouting their wi-fi password across their apartment, so now I just borrow their internet instead of paying for my own. My apartment is cheap, huge and extremely tastefully decorated, and so over the years several guys I’ve had the misfortune of dating have invited themselves to move in with me. I usually charge them for half of next-door’s internet connection. Those darn cable companies, always putting up the rates. It’s not the most ethical side of my life, but they usually turn out to be deadbeat wastrels who don’t end up paying for anything, so I don’t feel too bad.

It seems that most identity graphs use IP address and location data to link devices together. Devices that appear in the same place, on the same wi-fi network, probably belong to the same person. You might therefore think that an identity graph would find my apartment confusing. How is it meant to know which phone in the apartment is mine and which is Mike, Sanjit, Tom or other Sanjit’s? If the identity graph can’t figure this out then Mike will get shown ads for ping-pong bats and I’ll get shown ads for stupid goddamn bullshit. But distinguishing between people who live in the same place is not so hard given enough data. Perhaps they notice that my phone tends to connect to the same coffee shop wifi as my laptop. Perhaps they also notice that Tom’s tablet and his other tablet (who has two tablets? Christ he was an idiot) both take trips to the West Coast at the same time. And then maybe there’s this other mystery device. They don’t have enough location data to know exactly who it belongs to, but they do notice that it spends a lot of time looking at ping-pong websites and zero time looking at websites about stupid goddamn bullshit. There’s a nearby cluster of devices that seem to belong to someone with much the same interests. They add the device into this cluster and consider the mystery solved.

Once an identity graph has correctly partitioned a tricky thicket of devices belonging to multiple people, they’ve also created several new dimensions of information. Not only have they grouped together all my devices, but they’ve also figured out where I spend a lot of my time and which other groups of devices and therefore people I spend it with. I can’t even imagine the advertising segments Facebook could generate using this data. “Young adult who has just left home.” “Parents of children who have all left home.” “Recent divorcee who doesn’t seem to want to talk about it.” As far as I can tell, they don’t use their identity graph in this way. I have no idea why not.

Why do advertisers need Identity Graphs?

Today’s multi-screen consumer will often see an ad for a product on one device, do further research on another, and actually buy the product on yet another. This makes it hard for advertisers to know that their original ad was what caused the eventual purchase. It’s hard for them to know if they are any good at their jobs, and this leads to a huge amount of existential angst in the online marketing community.

To solve this problem, tracking companies build identity graphs. An identity graph consists of a web of devices and ownership links between them. Advertisers can use an identity graph to see that the user who just bought some acai berries on their laptop had previously seen five banner ads for them on their phone and tablet.

Vanilla single-device online trackers assign your device a persistent ID, store it on your device (usually in a cookie) and use it to track your behavior. I read a really good summary of how they work pitched at just the right level of technical detail, I’ll send you the link. By contrast, whilst multi-device trackers start by assigning and tracking IDs in the same way, they add an additional layer of intelligence to attempt to link together IDs of devices that belong to the same person.

Assigning IDs to your devices

Ad industry literature, like this 2015 white paper by AdBrain, describes two classes of tracking ID - deterministic and statistical. A deterministic ID is one that is explicitly assigned to and stored on a device. The most common types of deterministic identifier are Apple’s Identifier for Advertising (IDFA), Android’s Advertiser ID (AAID), and IDs generated by trackers and stored in cookies. These IDs are appended to requests sent to the tracker and allow them to identify a user with near certainty.

A statistical ID appears to be a euphemism for a device fingerprint, as AdBrain note on pWHATEVER of their white paper. Devices and browsers have a vast array of different settings and options; so many that the exact configuration on your device is very often unique to you. It’s as though you are the only person at your favorite fast-food chain who ever orders a vegan McMushroom burger with a side of kale and half a battery-farmed chicken. The fast-food chain could use your unique food order to follow your movements around the city and country, without even needing to use the tracking beacons they hide inside your…I’ve said too much. Anyway, online trackers can often access many of your device’s settings and turn them into a fingerprint that uniquely identifies you. They can identify and track you without having to store an identifier on your device. This means that there is nothing for you to delete, and no way to know if you are being tracked short of inspecting the requests coming out of your device, or just assuming that you are.

There are many ways an identity graph creator can tag a device with an ID. They can piggy-back off their existing service as a third-party tracker, sync their cookies with other trackers and share their data, or even sync their cookies with first-party websites that users have explicitly logged into.

Connecting your devices to each other

Once an identity graph creator has assigned IDs to devices, they build on this with a combination of ingenuity, purchased data and metadata leakage to connect together IDs and devices belonging to the same person.

The easiest and most reliable way for an identity graph to connect two devices is if it knows that the same person has explicitly logged in to an account of some kind on both devices. Facebook knows that all of your Facebook-enabled devices belong to you because you told them that they did. However, very few products have first-party data that covers a worthwhile fraction of internet users. Those that do typically aren’t sharing unless you buy ads on their platform.

Identity graph creators who don’t own a vast silo of first-party login data have to work harder. From reading ad industry blogs, it seems that the most common way that identity graphs connect devices is by looking at their IP address and therefore approximate location throughout the day. A phone and laptop that spend the evenings together in one location are probably a person’s personal devices. A second laptop that appears with the phone during the weekdays is probably their work computer. And that tablet that is also on their home network but only ever goes online past midnight is probably theirs too and we should just collect whatever data we can without asking too many probing questions.

Identity graph providers can further expand their reach by combining data they collect themselves with similar data held by second- and third-party sources, including other trackers. This can be vital, since they can only directly collect data for users of websites that use their tracking software. But if two trackers have databases of user behavior that contain user email addresses (which can come from all manner of different sources), then they can directly combine their databases by matching users by their email address (usually in a hashed, obfuscated form). They can combine databases of mobile behavior by comparing mobile advertising IDs (like IDFA and AAID). And they can even combine databases containing no personally identifiable information at all using cookie syncing.

Conclusion

There’s a concept in encryption called perfect forward secrecy. This is a property of some encryption protocols that keeps past communication secret, even if their private keys are compromised. I think of the modern internet as having perfect forward vulnerability - once your information gets out, there’s no way to make it private again. This is less of a problem when many little companies know a little bit about us, but as ever-bigger and more powerful trackers start to join the dots between our activity on more websites and devices, they begin to build up a distressingly detailed picture of us and our habits. This might be acceptable if we had more knowledge and control over what this data is used for. And I don’t know about you, but I sure don’t feel in control right now.

I did some pretty weird stuff on the internet back in the day. With hindsight I’m pretty sure that the other people on the forum were not actually seventeen and that those roubles did not come from a chain of hardware stores for the elderly. It wasn’t illegal as such, but it was certainly against the eBay terms of service and the scriptures of most (but interestingly not all) major religions.

I was very careful to only ever log in on a burner phone. Whilst I’m quite sure that the FBI won’t ever catch me, I still find it disconcerting that a company whose name starts with “Ad” and ends with a random noun has probably stitched together enough data sources to connect my laptop to my phone to my old phone to my old laptop to my old old phone to… None of this requires any special technology - just collecting and connecting all the data you can sniff out or buy. Nowadays I use an adblocker, a VPN and a new email address for every service or newsletter I sign up to, but I’m not even sure what exactly it is that I want to stay private from. I guess I’m afraid that we’re on a slippery slope, with no idea where it goes, and with a long way left to the bottom.

The ping-pong hall is long empty. Well, none of that sounds good for me, the consumer, you say. What can I do about it? Same as always, replies Wendy. Adblocker, VPN, Tor, Signal or Whatsapp, and don’t do anything you wouldn’t want your mother or toothpaste company to know about. Hey - shall we still try and throw Steve a fake birthday party next week?

You nod. She turns for the door. Still clearly extremely tired and delusional from a week of not sleeping, she trips over what appears to be absolutely nothing on her way out. You turn out the lights and head for your car. You feel a strange, inexplicable desire to purchase a Ford Mustang.