How to build a TCP proxy #1: Intro

31 Aug 2018

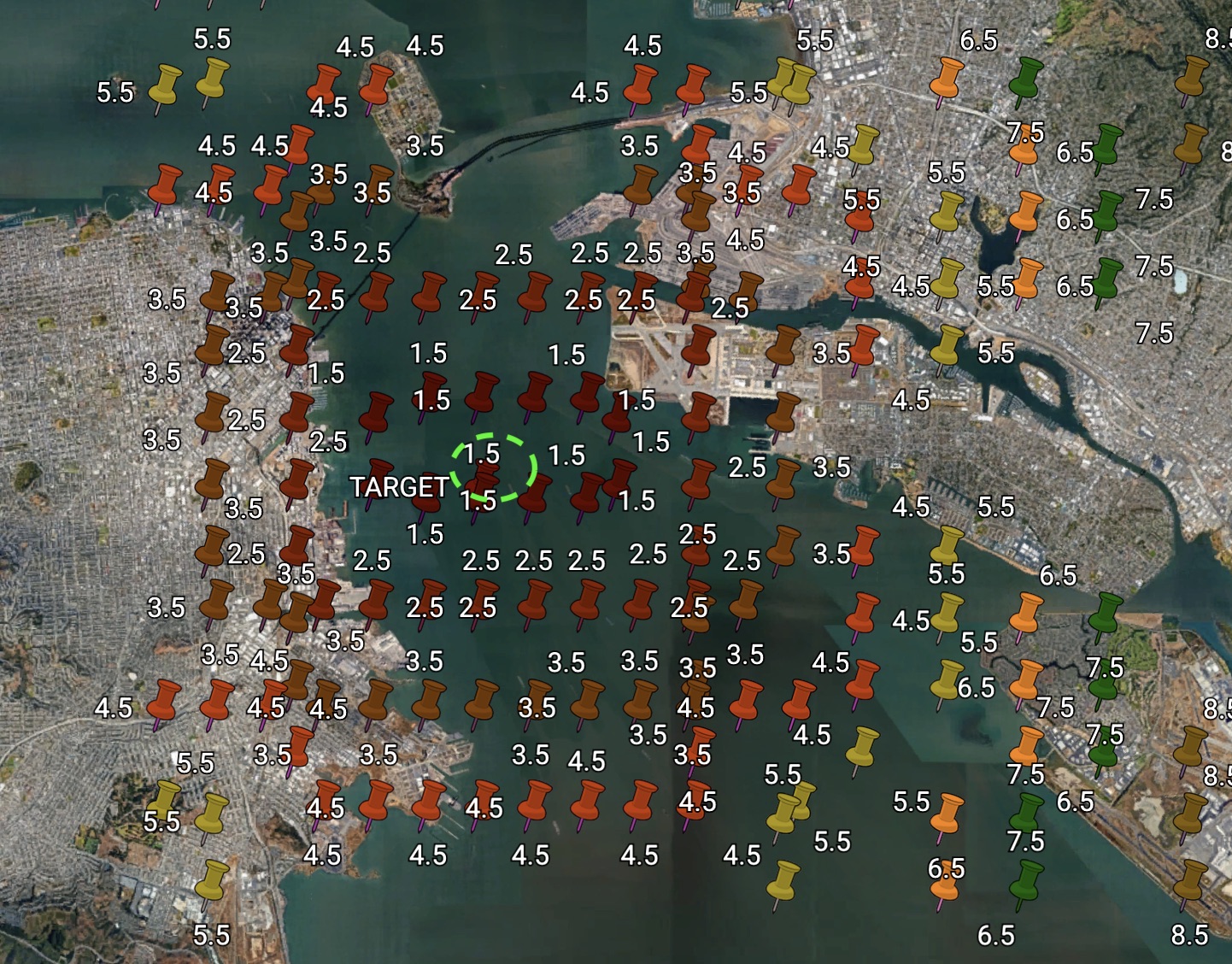

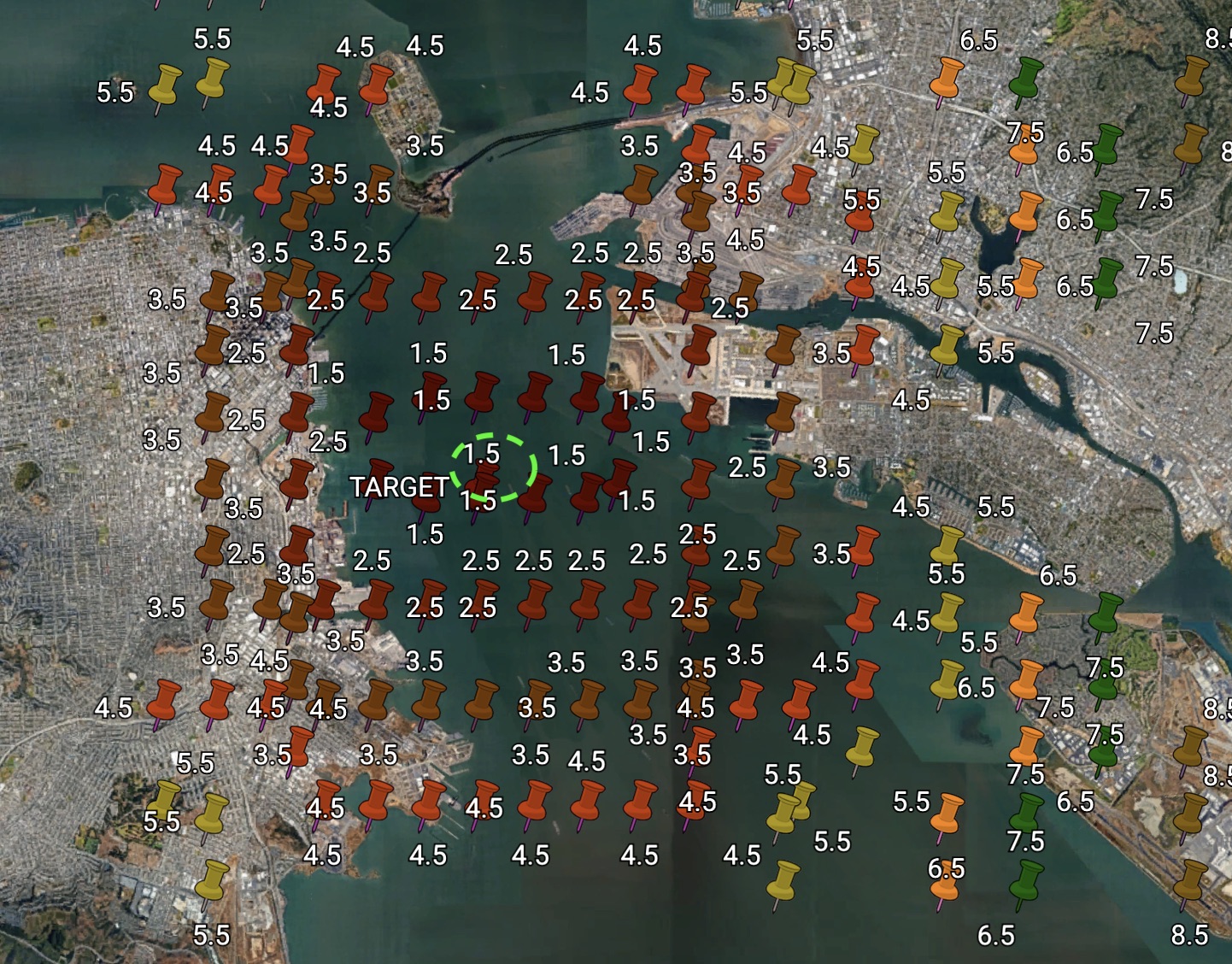

It was a weird and smoky afternoon in San Francisco. My downstairs neighbors had apparently never heard of vaporizers, and the Sierra Nevada was on fire. I had planned to spend the rest of the day attacking the user-location features of popular dating apps. I wanted to see whether any of them were vulnerable to attacks that could reverse engineer the position of a victim user. My plan was to spoof thousands of requests to each target app, pretend that each request was sent from a different location, and each time ask the app how far away my target was from my current, faked position. I would combine the results using maths and ingenuity to try and shake out an exact location.

The project started well. By using Burp Suite, a popular HTTP proxy, I could inspect, edit and replay all of the HTTP communication sent between my phone and the various dating apps’ remote servers. But when I started probing one very successful app, I immediately hit a brick wall. I found that its communication did not show up in Burp or any of my other standard, HTTP-focussed tools. I spent a long time checking and double-checking my settings and configurations. Eventually it hit me - they weren’t using HTTP at all. They were using some other, mysterious, but still TCP-based protocol that my normal tools, like Burp, were not able to work with.

Intrigued but wary, I took some time out to build a generic TCP proxy that could handle any TCP-based protocol, not just HTTP. Once complete, my proxy allowed me to inspect the uncooperative app’s communications with its servers. This meant that I could continue to creep on my fake dummy profile, with some promising results.

In this 4-part series, I will show you how to build a TCP proxy of your own. At the end of the project you’ll be able to use your proxy to intercept, record, edit, and replay all of your smartphone’s TCP traffic, not just HTTP. You’ll have learned a lot about many of the key technologies underpinning the internet, including DNS, TLS, and TCP. And you too will be able to try and rediscover the exact whereabouts of your own Testington McTest, age 28, lives in San Francisco, likes “Testing”.

1. What is a proxy?

A proxy is an intermediary that sends messages to a server on a client’s behalf. When browsing the internet using a proxy, you don’t directly ask Google “how do I cheat at poker?”. Instead you send a request to your proxy, asking it to ask Google how to cheat at poker for you. Your proxy asks Google, and sends you back the response. Google knows that it was talking to your proxy, but doesn’t necessarily know that it was you on the other side.

Proxies are widely used for privacy, content filtering, censorship bypassing, caching, and security penetration testing.

We are going to build a particular type of proxy known as a “man-in-the-middle” (MITM). MITM proxies are commonly used by security penetration testers in order to read, log, and modify the data that a client (like a smartphone) exchanges with a remote server (like a dating app).

Suppose that you wanted to use a MITM proxy (running on your own laptop) to inspect the traffic sent to and from your favorite dating app. You would instruct your smartphone to send its traffic to your MITM proxy, instead of sending it directly to the dating app’s servers. Your smartphone would no longer ask the dating app’s servers “how far away is Alex?”. Rather, it would ask your MITM proxy to ask the dating app how far away Alex is on your behalf.

Your MITM proxy would make this request, and send back to your smartphone any response that it got. It would also log the contents of the request and response to a file, allowing you to see what they contained. This is what makes a proxy a man-in-the-middle. You could use the information from these logs to modify requests from your smartphone on their way out, or even to spoof your own requests entirely from scratch.

2. Proxy Design

Our proxy will consist of 3 components, each of which solves a different problem:

- A fake DNS Server, to trick your smartphone into sending its TCP traffic to our proxy

- A Proxy Server, to manage data flow between your smartphone and the remote server

- A fake Certificate Authority, to handle TLS encryption between your smartphone and our proxy

This project is divided into 4 installments. This first installment gives an overview of the proxy’s design, and an introduction to the protocols and techniques that we will be using. The final three installments each describe how to build one of the above components, and give some extra color on the technologies involved.

2.1 Building a Fake DNS Server

We’re going to start by building a Fake DNS Server and using it to persuade your smartphone to send its traffic to our proxy.

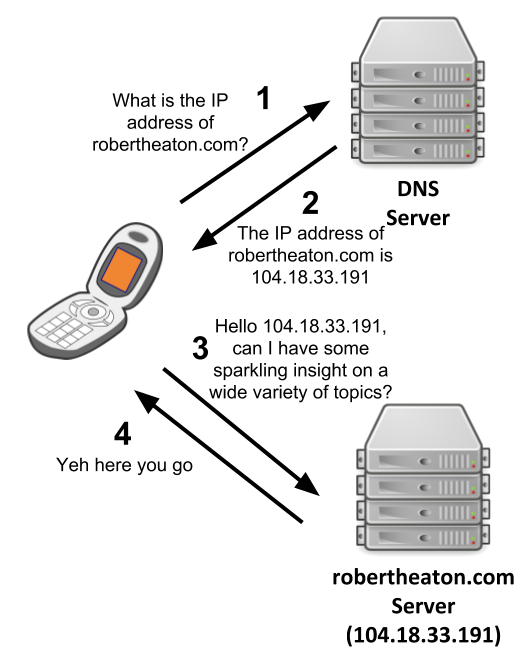

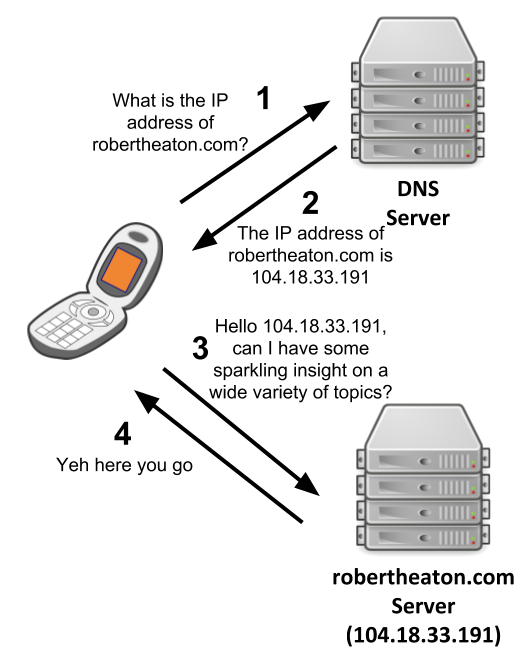

We humans think about sending data onto the internet using hostnames, like robertheaton.com. However, the internet routes our data to its destination using IP addresses, like 104.18.33.191. These two address systems are entirely distinct. IP addresses are inconvenient for humans (“visit my website at 104.18.33.191” is not very snappy), but hostnames mean absolutely nothing to the internet backbone.

Devices, like your smartphone, translate between hostnames and IP addresses using the Domain Name System (DNS) protocol. There are 20 or so free and public DNS servers that each (roughly speaking) keep a database of all the mappings from hostnames to IP addresses. Google has a DNS server with IP address 8.8.8.8. Verisign has one at 64.6.64.6 .

Suppose that you browse to my website, at robertheaton.com. Before your device can send a request to my server, it needs to turn this hostname into an IP address that the internet backbone can understand. It makes a DNS A record request (from now on referred to simply as a “DNS request”) to a DNS server, asking it to translate robertheaton.com into an IP address. Once the DNS server responds with 104.18.33.191, your browser sends an HTTP request out onto the internet, addressed to this IP address.

You can choose which DNS server your smartphone uses to make these DNS translations by typing the server’s IP address into your smartphone’s system settings. All of the major DNS servers should give the same, correct answers, so usually this choice doesn’t really matter much.

Usually.

2.1.1 What is a fake DNS server?

There’s nothing special about a DNS server. It’s just a server that listens for and responds to DNS requests on UDP port 53. In fact, we can run a DNS server of our own on your laptop, and we can configure your smartphone to use this fake DNS server instead of Google’s or Verizon’s.

This is more than just an oddity. We can program our fake DNS server to send back any DNS response that we like. We can even make it send back total lies. Suppose that our DNS server receives a DNS request for a hostname whose requests we want to route through our proxy (say, api.targetapp.com). We will program our server to respond, not with api.targetapp.com’s real IP address, but with the local IP address of your laptop.

Your phone won’t know that we are lying, and won’t see anything wrong with our response. It will accept that api.targetapp.com resolves to your laptop’s local IP address, and dispatch any data that it wants to send to api.targetapp.com to your laptop.

To take advantage of this behavior and receive this rerouted data, we will need to set up a second server on your laptop. This will be the actual proxy server. It will be responsible for receiving data from your phone; reading and printing it so that we can inspect it; and finally forwarding it on to its intended recipient.

2.1.2 Why can’t we just do what Burp does?

HTTP/S proxies like Burp don’t need to do any DNS jiggery-pokery in order to get your smartphone to send data to them. Why does our TCP proxy?

The answer is that HTTP/S proxies like Burp make extensive us of several first-class features of the HTTP protocol that only exist in order to help proxies. These include CONNECT requests and the HTTP Host header, more on which later.

All sensible smartphones take advantage of these features, and therefore work well with HTTP/S proxies. Your smartphone has a system setting that allows you to specify a proxy that it should use for all of its HTTP requests. In order to use an HTTP MITM proxy like Burp, you first connect your laptop and smartphone to the same network, and then tell your smartphone to use your laptop’s local IP address as an HTTP proxy. You open your Burp proxy on your laptop, and your smartphone obediently forwards all of its HTTP/S traffic to your laptop. Burp is instantly up and running.

But since we want our proxy to be capable of handling all TCP-based protocols, not just HTTP, we cannot take advantage of any HTTP-specific features. This is why we have to resort to our DNS hijinks. Other TCP-based protocols that you encounter may well have their own equivalent proxy-friendly features, but equally they may not. And you won’t know whether the particular protocol you’re inspecting has any such features until you’re able to inspect its requests using a proxy, and you won’t know how to proxy its requests until you’ve inspected its requests, and… Instead of wondering whether the chicken or the egg came first, you will have nothing but an empty chicken coop and broken dreams.

Now that we know how to trick your smartphone into sending its TCP data to your laptop, let’s see how we can do something with it.

2.2 The Proxy Server

The second piece of our system it the proxy server itself. This will be a server that runs on your laptop. It will accept traffic from your smartphone (with a little help from our fake DNS server), forward it to the target app’s remote server, and send any response that it gets back to your smartphone.

The main problem we will have to solve is making sure our proxy knows which remote server to forward your smartphone’s traffic to. Proxies, like all computer programs, are dumb as bricks. They don’t magically know what to do with the data they receive, and the only way they can know is if they are explicitly told.

When you want to arrange dinner with your friend, you send a text to their phone number saying “Want to get dinner tonight?” This works well, unless your friend is particularly flakey or doesn’t actually like you all that much.

Now imagine that you have a personal assistant who you employ as a proxy for all your texts. You send all your texts to your PA, and they forward them on to your friends and enemies on your behalf. If you send a text to your PA saying simply “Want to get dinner tonight?” then they won’t know who to forward it to. Since you have been a very unforgiving boss recently, your poor, presumably underpaid assistant will panic, delete the message, and pretend that they never received it.

There are many ways to address this PA proxy problem. You could attach a header to the message saying “Send-To: 415-123-1234”. Or you could establish a rule ahead of time that all dinner suggestions should always be routed to your mother.

Once again, HTTP/S proxies can solve this routing challenge easily using special, proxy-specific features of the HTTP protocol. And once again, we can’t use them, because we want our TCP proxy to be completely application-protocol-agnostic.

We’re therefore going to cheat a bit. We’re going to hardcode a hostname into our proxy, and tell our proxy to forward all of the data it receives to this host. This is like telling your PA to route all the text messages you send them today to your good buddy, Steve Steveington.

This is a reasonable simplification. You’re usually going to be using your proxy to inspect data sent by a single app. This app will probably send all of its interesting data to a single hostname, like api.targetapp.com.

We can look at the logs of our fake DNS server from the previous section, and see the list of hosts that your phone is trying to contact. We can use intuition and guesswork to figure out the hostname that is most interesting to us. For example, api.targetapp.com is probably more interesting than stats.mobileanalytics.com. Then we can hard-code this hostname into our proxy, and instruct our proxy to send all of the data it receives from your smartphone over to this host.

Note that we will need to configure our fake DNS server to only send our proxy traffic that is intended for the same hostname that our proxy is sending all its data to. For all other hostnames our fake DNS server should make a real DNS request to a real DNS server, and forward this real response to your smartphone. This will cause your smartphone to send all of its traffic for these hostnames directly to the right place, bypassing our proxy. If we did not do this, our proxy could end up forwarding sensitive data to the wrong servers.

2.2.1 How does Burp route requests?

I mentioned that Burp and other HTTP/S proxies route requests using special features of the HTTP protocol. So that we know what we’re missing out on, let’s take a look at these special features, and how they help proxies route both HTTP and HTTPS traffic.

HTTP

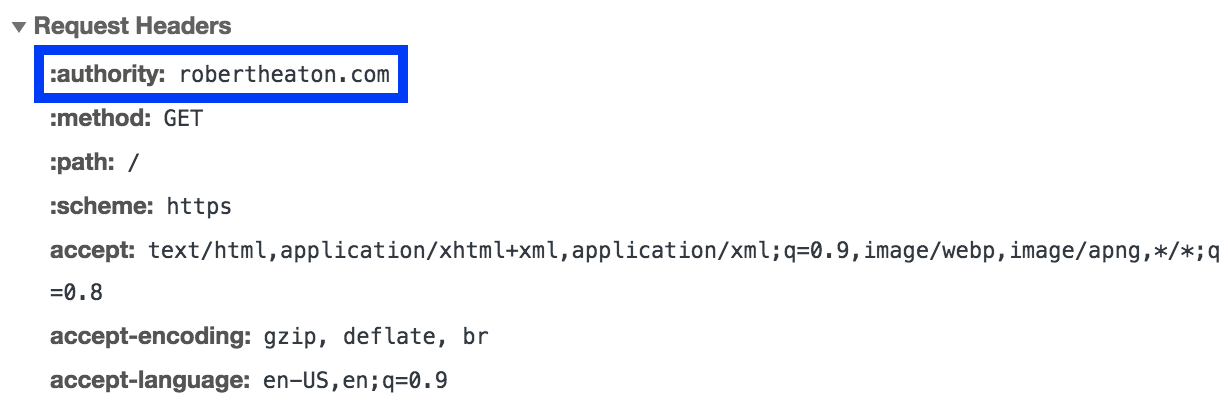

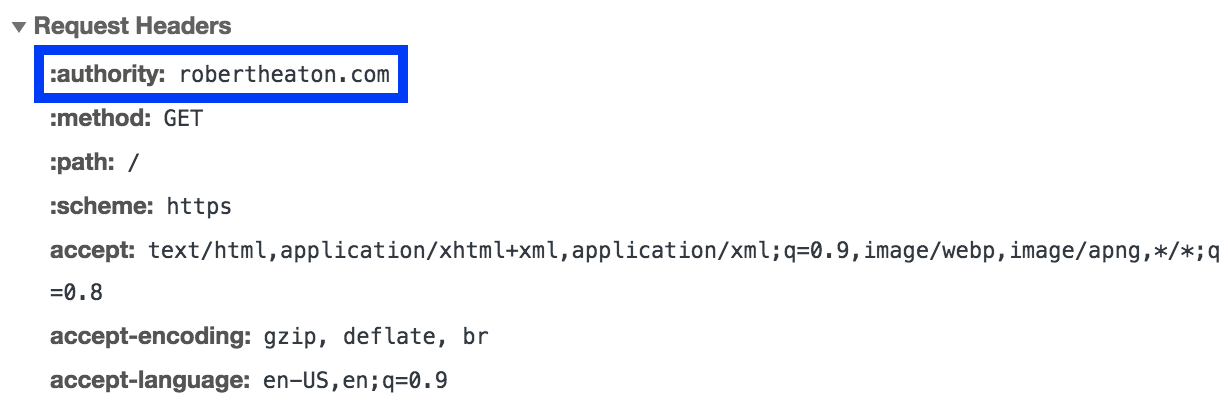

Unencrypted HTTP proxies have it easy. HTTP/1.x requests contain a Host header, which explicitly specifies the hostname that the request should be sent to. HTTP/2.x requests contain an authority pseudo-header containing the same information. HTTP proxies can easily parse out this values from the unencrypted request, and re-send the request accordingly. This is akin to including a “Send-To” field in your text messages to your assistant.

HTTPS

HTTPS proxies have it harder, although still not as hard as us.

There are 2 main types of HTTPS proxy - the forwarding proxy, and the man-in-the-middle. The “forwarding proxy” is very boring. It proxies HTTPS data without ever decrypting it. However, it can’t reuse the approach taken by HTTP proxies, because it only ever sees the data passing through it as unreadable, TLS-encrypted bytes of nonsense. This means that it can’t read the HTTP Host header, and so can’t use it to redirect the data passing through it. It needs an alternative solution. It’s no use sending your PA the encrypted name of your friend if they are unable to decrypt it.

The HTTPS protocol solves this problem by sending proxies an additional, proxy-specific CONNECT request. If a client knows that its HTTPS requests are going to be passing through a proxy, it precedes each of them with a separate HTTP CONNECT request. This request explicitly tells the proxy, in unencrypted plaintext, the hostname to which it should send the encrypted request that will follow shortly after. This means that the proxy does not need to decrypt the main payload in order to be able to route it correctly. This is like sending your PA a preliminary, unencrypted text message describing what they should do with the encrypted nonsense that you are about to send over.

The second type of HTTPS proxy, and the type that we are building, is the “man-in-the-middle” (MITM). As we have already discussed, a MITM differs from a forwarding proxy because it is able to decrypt and read the data that passes through it. This means that it can read the plaintext contents of an HTTP request, and so can also read the intended destination stored in its HTTP Host header. The HTTPS MITM can forward the request to this location, in exactly the same way as an HTTP proxy does.

MITMs still usually prefer to imitate forwarding proxies and use CONNECT requests where possible. The only time they use the Host header is when a “non-proxy-aware” client doesn’t know or doesn’t care that they are connected to a proxy, and do not send preliminary CONNECT requests. In this situation, the Host header is a useful fallback.

We now know how to persuade your smartphone to send its data to our proxy, and how to make sure our proxy receives this data safely. All that remains is for us to handle TLS encryption between your smartphone and our proxy.

2.3 The Fake Certificate Authority

Hopefully the TCP-based protocol that you are trying to inspect uses TLS encryption. It’s 2018, the internet is still a very dangerous place, and there’s no excuse for not encrypting absolutely everything.

TLS (sometimes known as SSL) is the form of encryption used by HTTPS in order to keep your online banking details safe. However, TLS can be used by any TCP-based protocol, not just HTTPS. This is because TLS doesn’t care about the form of the data it is encrypting. It can be HTTP, FTP, XML, or just total unstructured nonsense. This agnosticism means that our TCP proxy can reuse all the same TLS techniques commonly documented and used by HTTPS proxies.

The main TLS problem that we will need to solve is persuading your smartphone to trust our proxy. Once we have done this, the task of decrypting the data sent by your smartphone will be straightforward, because we can delegate it to known, well-tested libraries.

2.3.1 TLS Certificates and Certificate Authorities

Your smartphone is suspicious and untrusting of the outside world - and rightly so. How is it meant to know who that server claiming to represent api.targetapp.com really belongs to? There’s no point your smartphone carefully securing and encrypting your data if it then sends it to the wrong person.

TLS encryption soothes your smartphone’s paranoia, and makes our job slightly more difficult at the same time. TLS doesn’t just encrypt data before sending it; it also verifies that it is sending this encrypted data to the right place.

TLS connections are agreed and verified by a process known as a TLS handshake. During a TLS handshake, the client and server introduce themselves to each other. The client verifies the server’s identity (sometimes vice-versa as well), and the two parties agree on the encryption keys to use to secure their traffic. They exchange all of this information over a TCP connection.

Your smartphone will not complete a TLS handshake with our proxy unless we can prove our proxy’s identity by presenting it with a valid TLS certificate. We will need to set this TLS certificate’s Common Name (a field in the certificate) to the hostname that your smartphone thinks it is talking to. This will be easy enough. We will also need to sign the TLS certificate using a Root Certificate Authority (CA) that your smartphone trusts. This will be rather more difficult.

A real TLS certificate for a hostname like google.com, signed by a real CA like Digicert, would be among the most valuable few thousand bytes in the history of the world, as it would allow a malicious actor to decrypt all encrypted traffic sent by anyone to google.com. If you are in possession of such a certificate, stop reading immediately and put in on eBay.

Since we don’t have any real, CA-signed TLS certificates, we’re going to make our own, fake CA, called “Robert’s Trusty Certificate Authority”. We will generate a signing certificate for our CA, and install this certificate on your smartphone as a root CA. This will cause your smartphone to trust both our CA, and, more importantly, all other certificates that our CA signs. Whenever your smartphone asks our proxy to perform a TLS handshake, we’ll check the hostname that your smartphone believes it is talking to. We’ll quickly generate a certificate for that hostname (say, api.targapp.com), sign it with our fake CA, and present it to your smartphone. Your smartphone will see that this certificate for api.targapp.com is signed by “Robert’s Trusty Certificate Authority”, see that this reputable organization is in its list of trusted CAs, and happily complete a TLS handshake with our proxy.

With a TLS connection between your smartphone and our proxy successfully established, the rest of our system will work exactly as planned. Our TCP proxy will be complete.

3. The Project

This project is divided into 3 sections, each of which describes how to build one of our proxy’s 3 components:

- A fake DNS Server - a DNS server that runs on your laptop and tricks your smartphone into sending its TCP traffic to your laptop

- A Proxy Server - a server that runs on your laptop and juggles traffic between your smartphone and the remote server

- A fake Certificate Authority - a tool to generate TLS certificates that your smartphone will trust

After completing all 3 sections you will have a fully working TCP proxy that you can use to inspect and analyze any TCP-based protocol. I’ve written example code for each section using Python3. Whilst this does mean that you’ll be best off using Python3 too, implementing the project in another language is also completely fine and doable.

Let’s inspect some TCP protocols.

Read on - Part 2: Fake DNS Server

It was a weird and smoky afternoon in San Francisco. My downstairs neighbors had apparently never heard of vaporizers, and the Sierra Nevada was on fire. I had planned to spend the rest of the day attacking the user-location features of popular dating apps. I wanted to see whether any of them were vulnerable to attacks that could reverse engineer the position of a victim user. My plan was to spoof thousands of requests to each target app, pretend that each request was sent from a different location, and each time ask the app how far away my target was from my current, faked position. I would combine the results using maths and ingenuity to try and shake out an exact location.

The project started well. By using Burp Suite, a popular HTTP proxy, I could inspect, edit and replay all of the HTTP communication sent between my phone and the various dating apps’ remote servers. But when I started probing one very successful app, I immediately hit a brick wall. I found that its communication did not show up in Burp or any of my other standard, HTTP-focussed tools. I spent a long time checking and double-checking my settings and configurations. Eventually it hit me - they weren’t using HTTP at all. They were using some other, mysterious, but still TCP-based protocol that my normal tools, like Burp, were not able to work with.

Intrigued but wary, I took some time out to build a generic TCP proxy that could handle any TCP-based protocol, not just HTTP. Once complete, my proxy allowed me to inspect the uncooperative app’s communications with its servers. This meant that I could continue to creep on my fake dummy profile, with some promising results.

In this 4-part series, I will show you how to build a TCP proxy of your own. At the end of the project you’ll be able to use your proxy to intercept, record, edit, and replay all of your smartphone’s TCP traffic, not just HTTP. You’ll have learned a lot about many of the key technologies underpinning the internet, including DNS, TLS, and TCP. And you too will be able to try and rediscover the exact whereabouts of your own Testington McTest, age 28, lives in San Francisco, likes “Testing”.

1. What is a proxy?

A proxy is an intermediary that sends messages to a server on a client’s behalf. When browsing the internet using a proxy, you don’t directly ask Google “how do I cheat at poker?”. Instead you send a request to your proxy, asking it to ask Google how to cheat at poker for you. Your proxy asks Google, and sends you back the response. Google knows that it was talking to your proxy, but doesn’t necessarily know that it was you on the other side.

Proxies are widely used for privacy, content filtering, censorship bypassing, caching, and security penetration testing.

We are going to build a particular type of proxy known as a “man-in-the-middle” (MITM). MITM proxies are commonly used by security penetration testers in order to read, log, and modify the data that a client (like a smartphone) exchanges with a remote server (like a dating app).

Suppose that you wanted to use a MITM proxy (running on your own laptop) to inspect the traffic sent to and from your favorite dating app. You would instruct your smartphone to send its traffic to your MITM proxy, instead of sending it directly to the dating app’s servers. Your smartphone would no longer ask the dating app’s servers “how far away is Alex?”. Rather, it would ask your MITM proxy to ask the dating app how far away Alex is on your behalf.

Your MITM proxy would make this request, and send back to your smartphone any response that it got. It would also log the contents of the request and response to a file, allowing you to see what they contained. This is what makes a proxy a man-in-the-middle. You could use the information from these logs to modify requests from your smartphone on their way out, or even to spoof your own requests entirely from scratch.

2. Proxy Design

Our proxy will consist of 3 components, each of which solves a different problem:

- A fake DNS Server, to trick your smartphone into sending its TCP traffic to our proxy

- A Proxy Server, to manage data flow between your smartphone and the remote server

- A fake Certificate Authority, to handle TLS encryption between your smartphone and our proxy

This project is divided into 4 installments. This first installment gives an overview of the proxy’s design, and an introduction to the protocols and techniques that we will be using. The final three installments each describe how to build one of the above components, and give some extra color on the technologies involved.

2.1 Building a Fake DNS Server

We’re going to start by building a Fake DNS Server and using it to persuade your smartphone to send its traffic to our proxy.

We humans think about sending data onto the internet using hostnames, like robertheaton.com. However, the internet routes our data to its destination using IP addresses, like 104.18.33.191. These two address systems are entirely distinct. IP addresses are inconvenient for humans (“visit my website at 104.18.33.191” is not very snappy), but hostnames mean absolutely nothing to the internet backbone.

Devices, like your smartphone, translate between hostnames and IP addresses using the Domain Name System (DNS) protocol. There are 20 or so free and public DNS servers that each (roughly speaking) keep a database of all the mappings from hostnames to IP addresses. Google has a DNS server with IP address 8.8.8.8. Verisign has one at 64.6.64.6 .

Suppose that you browse to my website, at robertheaton.com. Before your device can send a request to my server, it needs to turn this hostname into an IP address that the internet backbone can understand. It makes a DNS A record request (from now on referred to simply as a “DNS request”) to a DNS server, asking it to translate robertheaton.com into an IP address. Once the DNS server responds with 104.18.33.191, your browser sends an HTTP request out onto the internet, addressed to this IP address.

You can choose which DNS server your smartphone uses to make these DNS translations by typing the server’s IP address into your smartphone’s system settings. All of the major DNS servers should give the same, correct answers, so usually this choice doesn’t really matter much.

Usually.

2.1.1 What is a fake DNS server?

There’s nothing special about a DNS server. It’s just a server that listens for and responds to DNS requests on UDP port 53. In fact, we can run a DNS server of our own on your laptop, and we can configure your smartphone to use this fake DNS server instead of Google’s or Verizon’s.

This is more than just an oddity. We can program our fake DNS server to send back any DNS response that we like. We can even make it send back total lies. Suppose that our DNS server receives a DNS request for a hostname whose requests we want to route through our proxy (say, api.targetapp.com). We will program our server to respond, not with api.targetapp.com’s real IP address, but with the local IP address of your laptop.

Your phone won’t know that we are lying, and won’t see anything wrong with our response. It will accept that api.targetapp.com resolves to your laptop’s local IP address, and dispatch any data that it wants to send to api.targetapp.com to your laptop.

To take advantage of this behavior and receive this rerouted data, we will need to set up a second server on your laptop. This will be the actual proxy server. It will be responsible for receiving data from your phone; reading and printing it so that we can inspect it; and finally forwarding it on to its intended recipient.

2.1.2 Why can’t we just do what Burp does?

HTTP/S proxies like Burp don’t need to do any DNS jiggery-pokery in order to get your smartphone to send data to them. Why does our TCP proxy?

The answer is that HTTP/S proxies like Burp make extensive us of several first-class features of the HTTP protocol that only exist in order to help proxies. These include CONNECT requests and the HTTP Host header, more on which later.

All sensible smartphones take advantage of these features, and therefore work well with HTTP/S proxies. Your smartphone has a system setting that allows you to specify a proxy that it should use for all of its HTTP requests. In order to use an HTTP MITM proxy like Burp, you first connect your laptop and smartphone to the same network, and then tell your smartphone to use your laptop’s local IP address as an HTTP proxy. You open your Burp proxy on your laptop, and your smartphone obediently forwards all of its HTTP/S traffic to your laptop. Burp is instantly up and running.

But since we want our proxy to be capable of handling all TCP-based protocols, not just HTTP, we cannot take advantage of any HTTP-specific features. This is why we have to resort to our DNS hijinks. Other TCP-based protocols that you encounter may well have their own equivalent proxy-friendly features, but equally they may not. And you won’t know whether the particular protocol you’re inspecting has any such features until you’re able to inspect its requests using a proxy, and you won’t know how to proxy its requests until you’ve inspected its requests, and… Instead of wondering whether the chicken or the egg came first, you will have nothing but an empty chicken coop and broken dreams.

Now that we know how to trick your smartphone into sending its TCP data to your laptop, let’s see how we can do something with it.

2.2 The Proxy Server

The second piece of our system it the proxy server itself. This will be a server that runs on your laptop. It will accept traffic from your smartphone (with a little help from our fake DNS server), forward it to the target app’s remote server, and send any response that it gets back to your smartphone.

The main problem we will have to solve is making sure our proxy knows which remote server to forward your smartphone’s traffic to. Proxies, like all computer programs, are dumb as bricks. They don’t magically know what to do with the data they receive, and the only way they can know is if they are explicitly told.

When you want to arrange dinner with your friend, you send a text to their phone number saying “Want to get dinner tonight?” This works well, unless your friend is particularly flakey or doesn’t actually like you all that much.

Now imagine that you have a personal assistant who you employ as a proxy for all your texts. You send all your texts to your PA, and they forward them on to your friends and enemies on your behalf. If you send a text to your PA saying simply “Want to get dinner tonight?” then they won’t know who to forward it to. Since you have been a very unforgiving boss recently, your poor, presumably underpaid assistant will panic, delete the message, and pretend that they never received it.

There are many ways to address this PA proxy problem. You could attach a header to the message saying “Send-To: 415-123-1234”. Or you could establish a rule ahead of time that all dinner suggestions should always be routed to your mother.

Once again, HTTP/S proxies can solve this routing challenge easily using special, proxy-specific features of the HTTP protocol. And once again, we can’t use them, because we want our TCP proxy to be completely application-protocol-agnostic.

We’re therefore going to cheat a bit. We’re going to hardcode a hostname into our proxy, and tell our proxy to forward all of the data it receives to this host. This is like telling your PA to route all the text messages you send them today to your good buddy, Steve Steveington.

This is a reasonable simplification. You’re usually going to be using your proxy to inspect data sent by a single app. This app will probably send all of its interesting data to a single hostname, like api.targetapp.com.

We can look at the logs of our fake DNS server from the previous section, and see the list of hosts that your phone is trying to contact. We can use intuition and guesswork to figure out the hostname that is most interesting to us. For example, api.targetapp.com is probably more interesting than stats.mobileanalytics.com. Then we can hard-code this hostname into our proxy, and instruct our proxy to send all of the data it receives from your smartphone over to this host.

Note that we will need to configure our fake DNS server to only send our proxy traffic that is intended for the same hostname that our proxy is sending all its data to. For all other hostnames our fake DNS server should make a real DNS request to a real DNS server, and forward this real response to your smartphone. This will cause your smartphone to send all of its traffic for these hostnames directly to the right place, bypassing our proxy. If we did not do this, our proxy could end up forwarding sensitive data to the wrong servers.

2.2.1 How does Burp route requests?

I mentioned that Burp and other HTTP/S proxies route requests using special features of the HTTP protocol. So that we know what we’re missing out on, let’s take a look at these special features, and how they help proxies route both HTTP and HTTPS traffic.

HTTP

Unencrypted HTTP proxies have it easy. HTTP/1.x requests contain a Host header, which explicitly specifies the hostname that the request should be sent to. HTTP/2.x requests contain an authority pseudo-header containing the same information. HTTP proxies can easily parse out this values from the unencrypted request, and re-send the request accordingly. This is akin to including a “Send-To” field in your text messages to your assistant.

HTTPS

HTTPS proxies have it harder, although still not as hard as us.

There are 2 main types of HTTPS proxy - the forwarding proxy, and the man-in-the-middle. The “forwarding proxy” is very boring. It proxies HTTPS data without ever decrypting it. However, it can’t reuse the approach taken by HTTP proxies, because it only ever sees the data passing through it as unreadable, TLS-encrypted bytes of nonsense. This means that it can’t read the HTTP Host header, and so can’t use it to redirect the data passing through it. It needs an alternative solution. It’s no use sending your PA the encrypted name of your friend if they are unable to decrypt it.

The HTTPS protocol solves this problem by sending proxies an additional, proxy-specific CONNECT request. If a client knows that its HTTPS requests are going to be passing through a proxy, it precedes each of them with a separate HTTP CONNECT request. This request explicitly tells the proxy, in unencrypted plaintext, the hostname to which it should send the encrypted request that will follow shortly after. This means that the proxy does not need to decrypt the main payload in order to be able to route it correctly. This is like sending your PA a preliminary, unencrypted text message describing what they should do with the encrypted nonsense that you are about to send over.

The second type of HTTPS proxy, and the type that we are building, is the “man-in-the-middle” (MITM). As we have already discussed, a MITM differs from a forwarding proxy because it is able to decrypt and read the data that passes through it. This means that it can read the plaintext contents of an HTTP request, and so can also read the intended destination stored in its HTTP Host header. The HTTPS MITM can forward the request to this location, in exactly the same way as an HTTP proxy does.

MITMs still usually prefer to imitate forwarding proxies and use CONNECT requests where possible. The only time they use the Host header is when a “non-proxy-aware” client doesn’t know or doesn’t care that they are connected to a proxy, and do not send preliminary CONNECT requests. In this situation, the Host header is a useful fallback.

We now know how to persuade your smartphone to send its data to our proxy, and how to make sure our proxy receives this data safely. All that remains is for us to handle TLS encryption between your smartphone and our proxy.

2.3 The Fake Certificate Authority

Hopefully the TCP-based protocol that you are trying to inspect uses TLS encryption. It’s 2018, the internet is still a very dangerous place, and there’s no excuse for not encrypting absolutely everything.

TLS (sometimes known as SSL) is the form of encryption used by HTTPS in order to keep your online banking details safe. However, TLS can be used by any TCP-based protocol, not just HTTPS. This is because TLS doesn’t care about the form of the data it is encrypting. It can be HTTP, FTP, XML, or just total unstructured nonsense. This agnosticism means that our TCP proxy can reuse all the same TLS techniques commonly documented and used by HTTPS proxies.

The main TLS problem that we will need to solve is persuading your smartphone to trust our proxy. Once we have done this, the task of decrypting the data sent by your smartphone will be straightforward, because we can delegate it to known, well-tested libraries.

2.3.1 TLS Certificates and Certificate Authorities

Your smartphone is suspicious and untrusting of the outside world - and rightly so. How is it meant to know who that server claiming to represent api.targetapp.com really belongs to? There’s no point your smartphone carefully securing and encrypting your data if it then sends it to the wrong person.

TLS encryption soothes your smartphone’s paranoia, and makes our job slightly more difficult at the same time. TLS doesn’t just encrypt data before sending it; it also verifies that it is sending this encrypted data to the right place.

TLS connections are agreed and verified by a process known as a TLS handshake. During a TLS handshake, the client and server introduce themselves to each other. The client verifies the server’s identity (sometimes vice-versa as well), and the two parties agree on the encryption keys to use to secure their traffic. They exchange all of this information over a TCP connection.

Your smartphone will not complete a TLS handshake with our proxy unless we can prove our proxy’s identity by presenting it with a valid TLS certificate. We will need to set this TLS certificate’s Common Name (a field in the certificate) to the hostname that your smartphone thinks it is talking to. This will be easy enough. We will also need to sign the TLS certificate using a Root Certificate Authority (CA) that your smartphone trusts. This will be rather more difficult.

A real TLS certificate for a hostname like google.com, signed by a real CA like Digicert, would be among the most valuable few thousand bytes in the history of the world, as it would allow a malicious actor to decrypt all encrypted traffic sent by anyone to google.com. If you are in possession of such a certificate, stop reading immediately and put in on eBay.

Since we don’t have any real, CA-signed TLS certificates, we’re going to make our own, fake CA, called “Robert’s Trusty Certificate Authority”. We will generate a signing certificate for our CA, and install this certificate on your smartphone as a root CA. This will cause your smartphone to trust both our CA, and, more importantly, all other certificates that our CA signs. Whenever your smartphone asks our proxy to perform a TLS handshake, we’ll check the hostname that your smartphone believes it is talking to. We’ll quickly generate a certificate for that hostname (say, api.targapp.com), sign it with our fake CA, and present it to your smartphone. Your smartphone will see that this certificate for api.targapp.com is signed by “Robert’s Trusty Certificate Authority”, see that this reputable organization is in its list of trusted CAs, and happily complete a TLS handshake with our proxy.

With a TLS connection between your smartphone and our proxy successfully established, the rest of our system will work exactly as planned. Our TCP proxy will be complete.

3. The Project

This project is divided into 3 sections, each of which describes how to build one of our proxy’s 3 components:

- A fake DNS Server - a DNS server that runs on your laptop and tricks your smartphone into sending its TCP traffic to your laptop

- A Proxy Server - a server that runs on your laptop and juggles traffic between your smartphone and the remote server

- A fake Certificate Authority - a tool to generate TLS certificates that your smartphone will trust

After completing all 3 sections you will have a fully working TCP proxy that you can use to inspect and analyze any TCP-based protocol. I’ve written example code for each section using Python3. Whilst this does mean that you’ll be best off using Python3 too, implementing the project in another language is also completely fine and doable.

Let’s inspect some TCP protocols.

Read on - Part 2: Fake DNS Server