I Might Be Spartacus: a differential privacy marketplace

28 Oct 2018

“Welcome to The Talk Show with me, Martina Martingale.

“My guest tonight is Hobert Reaton, founder of “I Might Be Spartacus”, a company that he claims “helps people safely sell their own data online.” He also previously founded WeSeeYou, a nauseating adtech company, so I recommend that you remain skeptical of him until the end of this seven minute segment. Hobert, welcome to the show.”

“Thanks Martina, it’s great but already kind of uncomfortable to be here.”

“Tell me about I Might Be Spartacus.”

“I Might Be Spartacus allows you to sell your own data online. We are reshaping the global data marketplace to give you more power, money, and privacy. We allow you to lie to companies about your data, tell them that you are lying, and have them still happily and rationally pay you for your lies. We do all of this using a branch of mathematics known as “Differential Privacy”.

“Why is our work so important? Think about what happens when I give a company my data. What happens when a company knows what type of car I drive, how many siblings I have, what my salary is? I run real risks, and a lot of them. I run the risk that the company will be hacked and my data will be stolen. I run the risk that the company will resell my data without my permission. I run the risk that Netflix will make fun of me on Twitter. And I run the risk that I move society one step closer to a dystopian nightmare future in which everything is foreseen, nothing is new, and free will is exposed as an illusion surrounding computation.

“Given all of that, why do I still give companies my data? More to the point, why do I give it to them completely gratis? Three reasons. First, in theory it’s part of the price I pay them for their goods or services. Facebook and Twitter invoice me in data, not money, and Amazon probably charge me less cash than they would have if they weren’t getting lots of my data too, although this causality is harder to prove.

“Second, in theory my data can provide useful feedback that makes a company’s products better, and that’s a win-win for everyone. Probably. At the very least, it makes the company’s products more efficient at extracting further time and money and data from me, and depending on who your employer is that can often be the same thing as “better”.

“And this is all the free market doing its job, right? Previously I paid for goods and services using money, now I pay for them using data. But a free market is made up of well-informed participants making unfettered choices from a range of competitive options. This does not describe the market for data. The market for data has no supply or demand curves, and participants like me don’t have anything close to a full understanding of the hidden costs that we are paying or the value of what we’re giving up. And - this is the third and final reason why I give away so much of my data - if I don’t think I’m getting a good deal then the only alternatives I have are local community book shops and farmers’ markets.

“Tech stocks are not trading at levels that suggest a cut-throat, hyper-competitive environment. What we have now is a one-sided data marketplace. I Might Be Spartacus gives power to the second side.

“Here’s how it works: you collect as much or as little of your own, truthful data as you like and store it in an I Might Be Spartacus server that belongs to you and lives inside your house. This data can be anything from how many tubs of humous your smart-fridge gets through in a week, to how often you open your garage door, to how well your pacemaker is working.

“You then use our platform to strike deals to sell your data to companies. The prices you charge will depend on the data you are selling and the company you are selling it to. Maybe I’ll give the US Federal Reserve my food consumption data on the cheap to help them calculate accurate inflation figures, but charge Facebook through the nose for the exact same information.

“But price is not the only variable in these negotiations. I Might Be Spartacus’s big breakthrough is to allow you to set not just the price of the data that you sell, but also its precision. The question you have to answer is not “Do I trust company X with data Y?” The world is more complex than that. What you really have to work out is “how much do I trust company X with data Y?” This is where ‘Differential Privacy’ comes in.

“Differential Privacy is commonly used in social science research when researchers want to ask subjects about embarrassing or illegal activity. Suppose that I wanted to study the prevalence of heroin use in talk show studio audiences. I could interview members of your audience and straight up ask them ‘have you used heroin in the last week?’ However, anyone who had used heroin in the last week might reasonably be afraid that if they said ‘yes’ then I would turn them in to the police or their employer. I wouldn’t, for what it’s worth, but they have no reason to trust me.

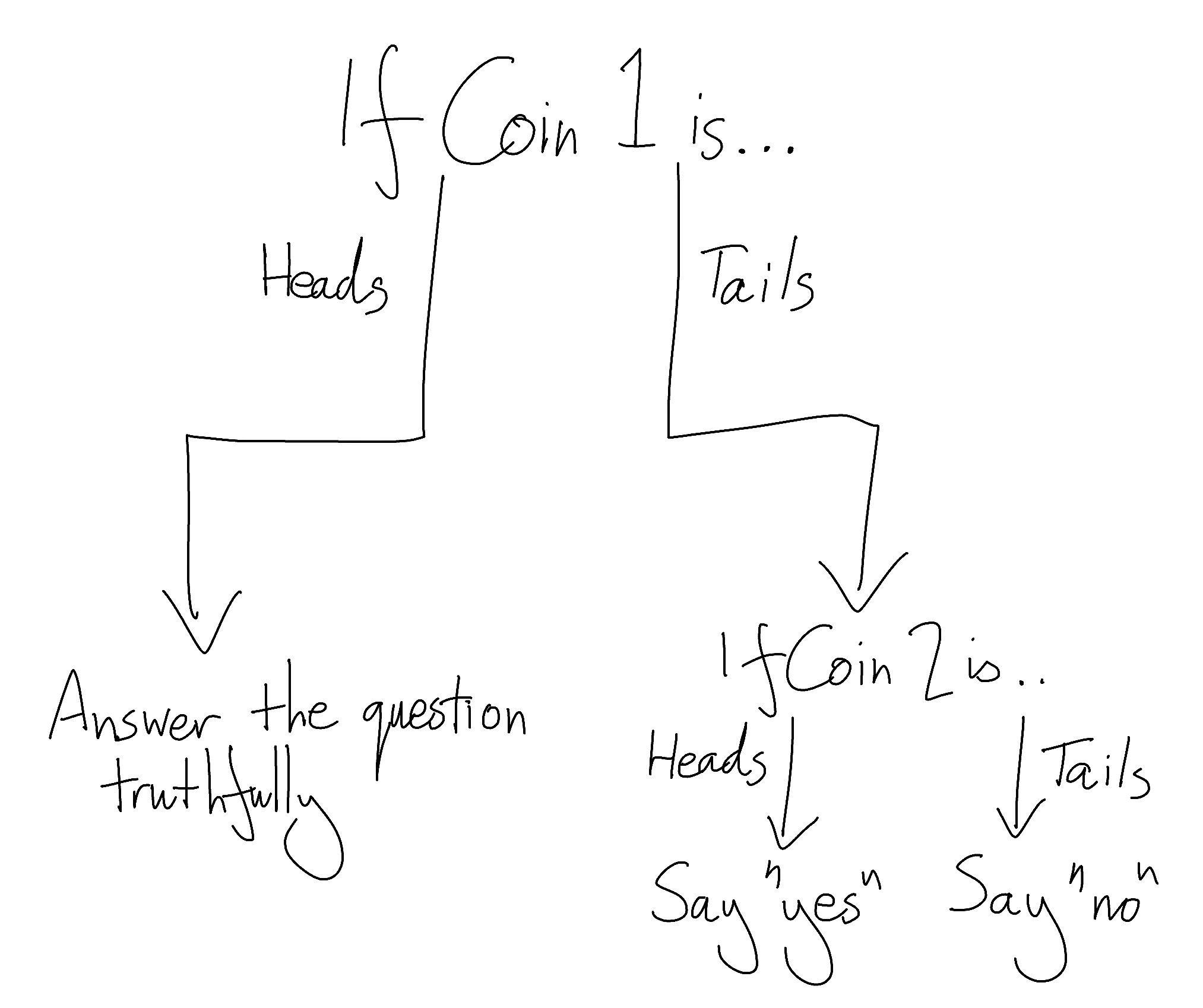

“So instead of demanding ‘have you used heroin in the last week?’ I would ask the audience to go through a simple 3-step process.

- Flip 2 coins, and don’t show me the outcomes

- If the first coin came up heads, truthfully answer the question ‘have you used heroin in the last week?’

- If the first coin came up tails, look at the second coin. If the second coin came up heads, reply ‘yes’, regardless of what the true answer to the question is. If it came up tails, reply ‘no’.’

“Here, I brought some slides to help.”

“Oh great, I wish more of my lighthearted talk-show guests brought slides.”

“OK then, no slides. Now if I report you to the police or your employer, or even if my dataset gets leaked to the world, you have ‘plausible deniability’. You can say ‘oh I only said ‘yes’ because my first coin came up tails and then I replied randomly.’ No one can prove that you’re lying.

“And the data is still useful to me. It’s noisy because it contains a lot of lies, but assuming that everyone follows my protocol, I get to control the parameters of the lies and make them symmetrical. This means that, given enough data, the lies should even out. I can still draw big picture conclusions like ‘more talk show audience men have recently used heroin than women’ or ‘most talk show audience members who have recently used heroin are in their twenties.’ But I have no way to reverse-engineer information like ‘this specific person has or has not recently used heroin’ beyond a low, fine-tunable degree of certainty. This is Differential Privacy.

“At I Might Be Spartacus, we allow you to use Differential Privacy to not only choose the price of the data that you sell, but how accurate it is and how much privacy you give up. Differential Privacy opens up a enormous menu of different ways to serve your data. For example, suppose that I’ve connected my bicycle to my data collection hub, and it knows the average length of my trips. I can make any or all of the following offers:

“Unilever, I hate you but I trust you to keep my data safe. You can have the real value for $100.”

“Happyvale Bicycle Club, I love you but I know that you’re going to keep all this data in a Google Spreadsheet set to public so that it’s easy for everyone to access. You can have the value with a lot of noise applied for free.”

“Tesla, I mostly trust you and I like the idea of electric cars. You can have a slightly noisy value for $5.”

“Once you’ve struck a deal with your customer, your I Might Be Spartacus data collection hub applies the agreed amount of random noise to your data. It sends this information to the I Might Be Spartacus servers, and we send it on to your customer. Even though your customer knows that you’re lying to them, they know the framework within which you are lying. They can still make good use of your information by aggregating it with thousands of other parameterized liars.”

“So who do we have to trust?”

“Us. A bit.”

“That’s not very comforting.”

“But it’s better than having to trust everyone, and much more productive than trusting no one. Remember Martina, you are the only person who ever gets noise-free access to your underlying data. All you send to your customers, and all you send to us, is the value after random noise has been applied. There are some interesting kinks to iron out to do with repeated exposure of correlated information, but my eggheads are working on that.”

“Well Hobert, you’ve filled up the Silicon Valley sketchy bingo card of using fancy math whilst waving your hands, telling people that all they have to do is trust you, and sweating a lot when interviewed. Anything else you’d like to say before you leave?”

“I have one parting shower thought. In order to give yourself plausible deniability, all you have to do is convince people that you’re using Differential Privacy. You don’t have to actually use it. As long as you believe that it’s possible that I only answered “yes” because the coins told me to, I am free to tell the truth with impunity. That’s all I’ve got to say today - Martina, thanks for having me.”

“Bye.”

“Welcome to The Talk Show with me, Martina Martingale.

“My guest tonight is Hobert Reaton, founder of “I Might Be Spartacus”, a company that he claims “helps people safely sell their own data online.” He also previously founded WeSeeYou, a nauseating adtech company, so I recommend that you remain skeptical of him until the end of this seven minute segment. Hobert, welcome to the show.”

“Thanks Martina, it’s great but already kind of uncomfortable to be here.”

“Tell me about I Might Be Spartacus.”

“I Might Be Spartacus allows you to sell your own data online. We are reshaping the global data marketplace to give you more power, money, and privacy. We allow you to lie to companies about your data, tell them that you are lying, and have them still happily and rationally pay you for your lies. We do all of this using a branch of mathematics known as “Differential Privacy”.

“Why is our work so important? Think about what happens when I give a company my data. What happens when a company knows what type of car I drive, how many siblings I have, what my salary is? I run real risks, and a lot of them. I run the risk that the company will be hacked and my data will be stolen. I run the risk that the company will resell my data without my permission. I run the risk that Netflix will make fun of me on Twitter. And I run the risk that I move society one step closer to a dystopian nightmare future in which everything is foreseen, nothing is new, and free will is exposed as an illusion surrounding computation.

“Given all of that, why do I still give companies my data? More to the point, why do I give it to them completely gratis? Three reasons. First, in theory it’s part of the price I pay them for their goods or services. Facebook and Twitter invoice me in data, not money, and Amazon probably charge me less cash than they would have if they weren’t getting lots of my data too, although this causality is harder to prove.

“Second, in theory my data can provide useful feedback that makes a company’s products better, and that’s a win-win for everyone. Probably. At the very least, it makes the company’s products more efficient at extracting further time and money and data from me, and depending on who your employer is that can often be the same thing as “better”.

“And this is all the free market doing its job, right? Previously I paid for goods and services using money, now I pay for them using data. But a free market is made up of well-informed participants making unfettered choices from a range of competitive options. This does not describe the market for data. The market for data has no supply or demand curves, and participants like me don’t have anything close to a full understanding of the hidden costs that we are paying or the value of what we’re giving up. And - this is the third and final reason why I give away so much of my data - if I don’t think I’m getting a good deal then the only alternatives I have are local community book shops and farmers’ markets.

“Tech stocks are not trading at levels that suggest a cut-throat, hyper-competitive environment. What we have now is a one-sided data marketplace. I Might Be Spartacus gives power to the second side.

“Here’s how it works: you collect as much or as little of your own, truthful data as you like and store it in an I Might Be Spartacus server that belongs to you and lives inside your house. This data can be anything from how many tubs of humous your smart-fridge gets through in a week, to how often you open your garage door, to how well your pacemaker is working.

“You then use our platform to strike deals to sell your data to companies. The prices you charge will depend on the data you are selling and the company you are selling it to. Maybe I’ll give the US Federal Reserve my food consumption data on the cheap to help them calculate accurate inflation figures, but charge Facebook through the nose for the exact same information.

“But price is not the only variable in these negotiations. I Might Be Spartacus’s big breakthrough is to allow you to set not just the price of the data that you sell, but also its precision. The question you have to answer is not “Do I trust company X with data Y?” The world is more complex than that. What you really have to work out is “how much do I trust company X with data Y?” This is where ‘Differential Privacy’ comes in.

“Differential Privacy is commonly used in social science research when researchers want to ask subjects about embarrassing or illegal activity. Suppose that I wanted to study the prevalence of heroin use in talk show studio audiences. I could interview members of your audience and straight up ask them ‘have you used heroin in the last week?’ However, anyone who had used heroin in the last week might reasonably be afraid that if they said ‘yes’ then I would turn them in to the police or their employer. I wouldn’t, for what it’s worth, but they have no reason to trust me.

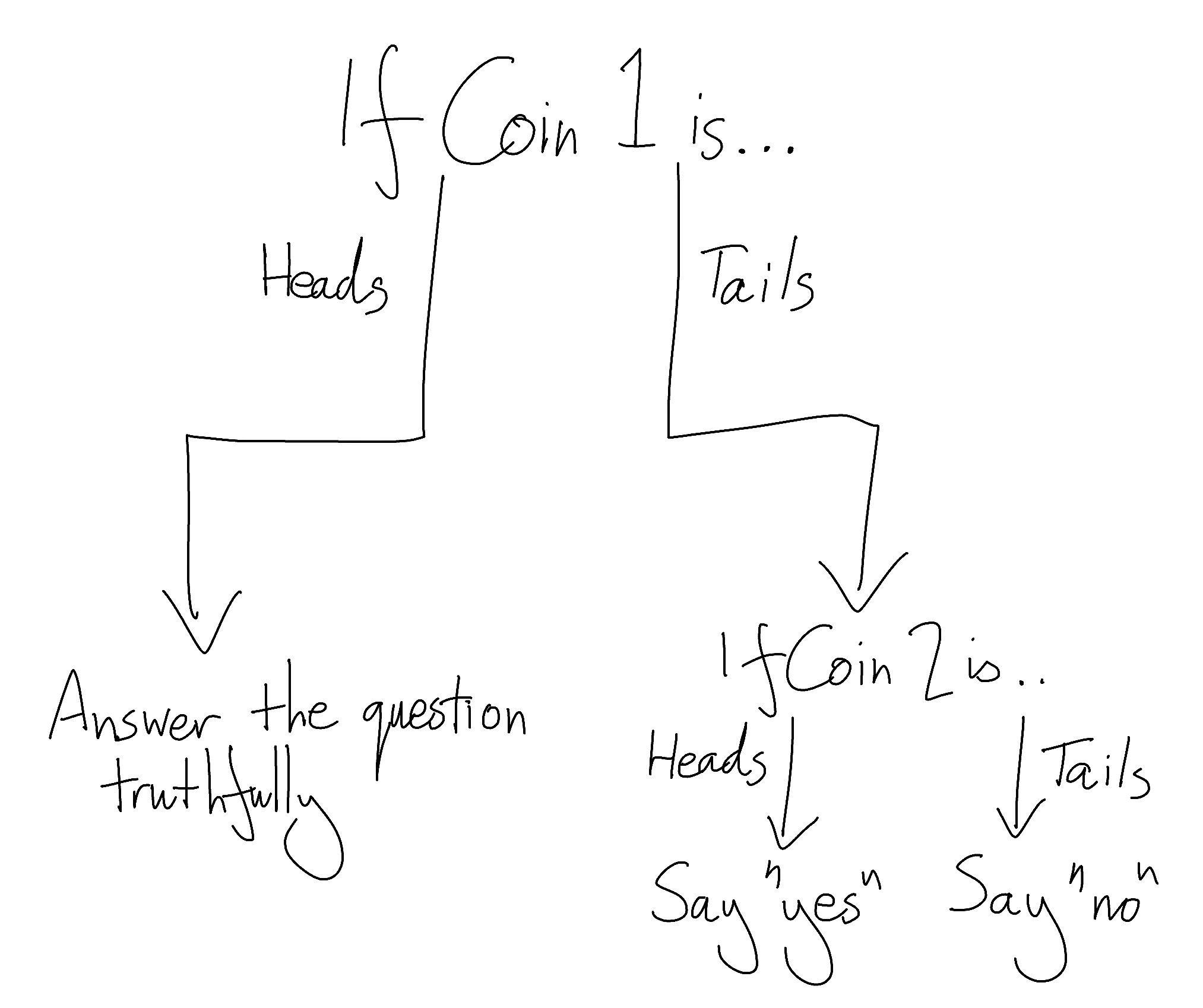

“So instead of demanding ‘have you used heroin in the last week?’ I would ask the audience to go through a simple 3-step process.

- Flip 2 coins, and don’t show me the outcomes

- If the first coin came up heads, truthfully answer the question ‘have you used heroin in the last week?’

- If the first coin came up tails, look at the second coin. If the second coin came up heads, reply ‘yes’, regardless of what the true answer to the question is. If it came up tails, reply ‘no’.’

“Here, I brought some slides to help.”

“Oh great, I wish more of my lighthearted talk-show guests brought slides.”

“OK then, no slides. Now if I report you to the police or your employer, or even if my dataset gets leaked to the world, you have ‘plausible deniability’. You can say ‘oh I only said ‘yes’ because my first coin came up tails and then I replied randomly.’ No one can prove that you’re lying.

“And the data is still useful to me. It’s noisy because it contains a lot of lies, but assuming that everyone follows my protocol, I get to control the parameters of the lies and make them symmetrical. This means that, given enough data, the lies should even out. I can still draw big picture conclusions like ‘more talk show audience men have recently used heroin than women’ or ‘most talk show audience members who have recently used heroin are in their twenties.’ But I have no way to reverse-engineer information like ‘this specific person has or has not recently used heroin’ beyond a low, fine-tunable degree of certainty. This is Differential Privacy.

“At I Might Be Spartacus, we allow you to use Differential Privacy to not only choose the price of the data that you sell, but how accurate it is and how much privacy you give up. Differential Privacy opens up a enormous menu of different ways to serve your data. For example, suppose that I’ve connected my bicycle to my data collection hub, and it knows the average length of my trips. I can make any or all of the following offers:

“Unilever, I hate you but I trust you to keep my data safe. You can have the real value for $100.” “Happyvale Bicycle Club, I love you but I know that you’re going to keep all this data in a Google Spreadsheet set to public so that it’s easy for everyone to access. You can have the value with a lot of noise applied for free.” “Tesla, I mostly trust you and I like the idea of electric cars. You can have a slightly noisy value for $5.”

“Once you’ve struck a deal with your customer, your I Might Be Spartacus data collection hub applies the agreed amount of random noise to your data. It sends this information to the I Might Be Spartacus servers, and we send it on to your customer. Even though your customer knows that you’re lying to them, they know the framework within which you are lying. They can still make good use of your information by aggregating it with thousands of other parameterized liars.”

“So who do we have to trust?”

“Us. A bit.”

“That’s not very comforting.”

“But it’s better than having to trust everyone, and much more productive than trusting no one. Remember Martina, you are the only person who ever gets noise-free access to your underlying data. All you send to your customers, and all you send to us, is the value after random noise has been applied. There are some interesting kinks to iron out to do with repeated exposure of correlated information, but my eggheads are working on that.”

“Well Hobert, you’ve filled up the Silicon Valley sketchy bingo card of using fancy math whilst waving your hands, telling people that all they have to do is trust you, and sweating a lot when interviewed. Anything else you’d like to say before you leave?”

“I have one parting shower thought. In order to give yourself plausible deniability, all you have to do is convince people that you’re using Differential Privacy. You don’t have to actually use it. As long as you believe that it’s possible that I only answered “yes” because the coins told me to, I am free to tell the truth with impunity. That’s all I’ve got to say today - Martina, thanks for having me.”

“Bye.”