ROBERT: prove that your randomized trial really was random

17 Mar 2019

All you need in order to run a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) is a few willing participants and a good source of randomness. With only these simple ingredients you can arbitrarily give half of your participants something that might be good; give the other nothing; and then watch and measure how things turn out. Your results are free from bias and confounding, thanks to the cleansing power of randomness.

This means that you’d better make sure that you get your randomness right. And to increase outside observer’s trust in your results, ideally you should be able to prove it. Lots of effort has therefore been put into making sure that hospital-based RCTs are shuffled properly. The result of this effort has been a wonderful combination of better science and entertaining stories of determined clinicians trying to cheat. Despite this, much less attention has been paid to RCTs run outside of hospitals.

Therefore, in this blog post I present the Randomize Optimally By Entirely Removing Trust (ROBERT) algorithm. Using some very mild cryptography, ROBERT allows researchers running non-hospital-based RCTs to generate trustworthy, replicable randomness. In this post I’ll describe why ROBERT is necessary, how it works, and how it can be improved.

Let’s begin our journey inside a hospital.

Hospital-based RCTs

Suppose that a researcher wants to test out a promising new cancer treatment. She decides to run an RCT with 100 cancer patients. She won’t begin her trial with all 100 participants fully enrolled and ready to go. Instead, she will have new patients referred to her over time, and she’ll gradually build up her trial population over several weeks or months. Whenever a new patient joins her trial, she’ll need to somehow assign them to either her control or treatment group.

Our researcher is probably torn between scientific truth and personal success. She does want to discover the reality of her new treatment, even if it doesn’t turn out to be the reality she was hoping for. But she also wants her photo to appear in medical textbooks with the caption “her father no longer questions her life choices”. This means that there’s a big part of our researcher that would quite like it if she got to choose how patients were assigned to the control and treatment groups. She could put all the promising patients in the treatment group, and all the desperate ones in the control. This would make for a positive result, but very bad science.

The whole point of an RCT is that control and treatment groups must be assigned at random. Generating a random assignment is a two-step process. First, our researcher must generate an unpredictable random sequence. Second, she must use her random sequence to randomly assign participants to trial groups. As we will see, even if a researcher generates a suitable sequence in step 1, she still has still an enormous amount of room for mistake and malfeasance in step 2.

Suppose that our researcher somehow knew that the next patient who enrolled in her study was going to be assigned to the treatment group. Our researcher might stop accepting sickly-looking patients, and start seeking out more sprightly-seeming ones instead. Our researcher need not exert this influence overtly, or even deliberately. As Detorri (2010) speculates:

Perhaps the patient hesitates briefly when the study is mentioned and the surgeon suggests that the patient sleep on the idea of participating. Maybe the surgeon decides to get more tests before offering enrollment. The number of different subtle possibilities to exclude this patient is only limited by one’s imagination.

This means that upcoming trial group assignments should be treated as top-secret, radioactive information, accessible only on a need-to-know basis. However, this is often not the case. Sometimes assignments are kept insufficiently secure, and sometimes they are even helpfully posted on bulletin boards in hospital common rooms. Some trials hide upcoming assignments inside sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes, which may only be opened once a patient has been officially enrolled in the study. But sneaky researchers have been known to hold these envelopes in front of a light bulb to try and peek at the group assignment contained within. Schulz and Grimes (2002) even describe how one researcher took a particularly thick envelope to their hospital’s X-ray wing so that they could blast it with the department’s powerful backlights. Schulz and Grimes also describe how one clinician mounted a night-raid on a chief investigators’ office in search of a master copy of future group assignments. People can do unprofessional things when their ideas are on the line.

There are two options available to a noble-minded researcher who wants to assure their readers that their study is truly random. First, they could use a centralized, third-party randomness management service like SealedEnvelope. These services generate, record, and safeguard group assignments, and prevent the research team from meddling with them.

Alternatively, the researcher could try to implement a bulletproof system of physical sealed envelopes, capable of standing up to even the most determined inspection and skullduggery. Such systems can get very fiddly, often involving hidden carbon paper, and yet they’re still likely to be vulnerable to a determined attacker with a little imagination.

Whichever way you approach it, proper group assignment can feel like a lot of elaborate work just to replace what is fundamentally a coin flip. However, this work appears to be crucial: according to Schulz and Grimes (2002), trials with inadequate or unclear allocation concealment produce estimates of effect that are up to 40% higher than their properly run counterparts. This is no idle concern.

RCTs outside the hospital

Because of this, well-run hospital-based RCTs are now randomized using piles of paranoia and plenty of precise procedures. However, to the best of my knowledge, much less scrutiny is leveled at the randomization of RCTs run outside of hospitals. Suppose that a development economist wants to investigate the effect of a new type of malaria treatment across a trial population of 400 villages. He decides to run a “cluster-RCT”, in which he assigns entire villages - instead of individuals - to control and treatment groups.

Unlike our medical researcher, our development economist starts his trial with a full list of all participating villages. He can therefore perform all of his randomization and group-assignment simultaneously, at the beginning of his trial. To my suspicious mind, this is a wonderful opportunity for shenanigans.

The academic community appears to broadly agree. Researchers often describe and justify their randomization procedures in the write-ups of their trials. They compare their treatment and control groups across a range of baseline characteristics (eg. age, income, wealth, health, family size), hoping to prove that randomness has done its job and that their trial groups are suitably similar. The Cochrane Collaboration, an organization that reviews and analyses academic research, requires its reviewers to check that papers report a proper randomization process. Those that do not are downgraded.

This is all much better than nothing. I’m sure that Doe et al are all very nice people once you get to know them. I can see that Doe generated his trial groups using “computer randomness”, and I agree that his tests of baseline balance all check out. But I still see a significant gap between claim and proof, which can only be crossed by trust. Trust is a flimsy material with which to build a bridge, and should only be used when no other alternative is available.

For example, how do I know that our researcher didn’t carefully “randomize” his groups so that they were balanced on all of the characteristics in his baseline balance tests, but extremely (or even just mildly) one-sided on some other, unobserved characteristics? I assume that he didn’t. But whenever you assume you make an “as” out of “sum” and “e”. It seems odd to me that we trust our development economist to generate his own randomness and group assignments, even though we know that medical researchers are perfectly willing to X-ray envelopes and ransack offices in order to try to influence theirs.

One way in which our researcher could partially increase my trust in him is through a public lottery. Our researcher could find a reputable person, perhaps someone from their trial participants’ community. Our researcher could have this person publicly draw names out of a hat, and use the results to assign treatment and control groups. This type of public lottery is definitely better and harder to fiddle with than a private spreadsheet. But as a post-hoc observer, I still can’t audit whether our researcher performed the lottery correctly, or even whether he performed it at all.

Our researcher could use the blockchain somehow. No, seriously - it would be hard to understand and easy to make fun of, but it would probably work. Or they could copy hospital RCT best practices, and contract their randomness out to an auditable third-party. But both of these approaches would add complexity. What if the third-party goes out of business? What if they get hacked? What if I, as an outside observer, am congenitally incapable of trusting anyone?

The solution: ROBERT

The solution is the Randomize Optimally By Entirely Removing Trust (ROBERT) algorithm. Using the ROBERT algorithm, our researcher can produce trial group assignments that are:

- Random - the basic criteria for a random assignment

- Replicable - an outside observer can rerun the algorithm and produce the same results. This means that they can verify that the assignment really was generated programmatically, and not by hand.

- Tamper-resistant - an outisde observer can be confident that, within certain parameters, the researcher has not tampered with the assignments by, for example, regenerating assignments until they find one that they like.

- Not reliant on any third-parties - there’s no need for researchers or observers to trust or talk to anyone. Assignment groups can be generated and verified without even an internet connection.

ROBERT achieves these properties by restricting our researcher’s randomization choices - or “degrees of freedom” - as much as possible. All the researcher gets to choose is their list of trial participants, and ROBERT deterministically turns this list into a single, verifiable group assignment. Because after all, what are choices but an opportunity to fiddle with your RCT?

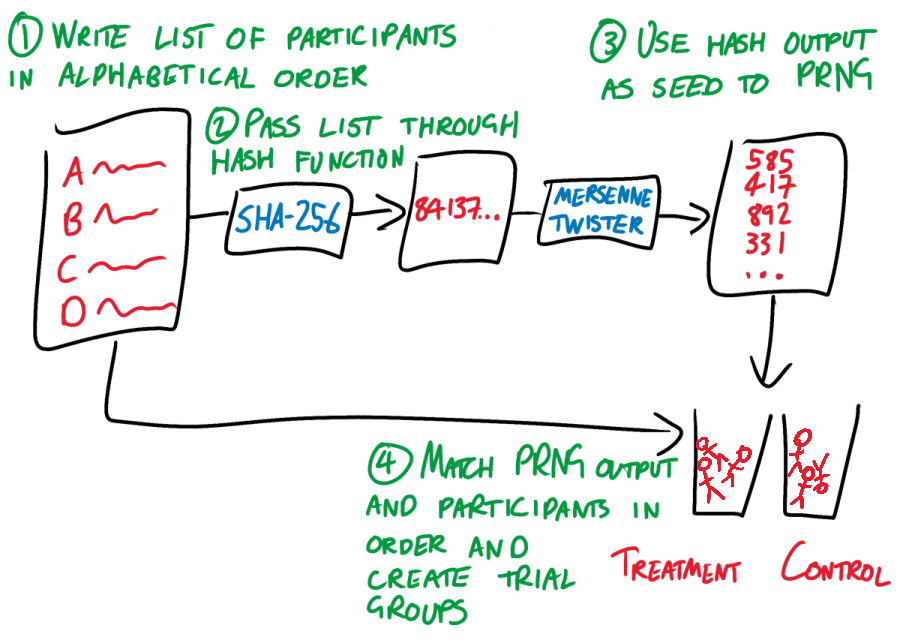

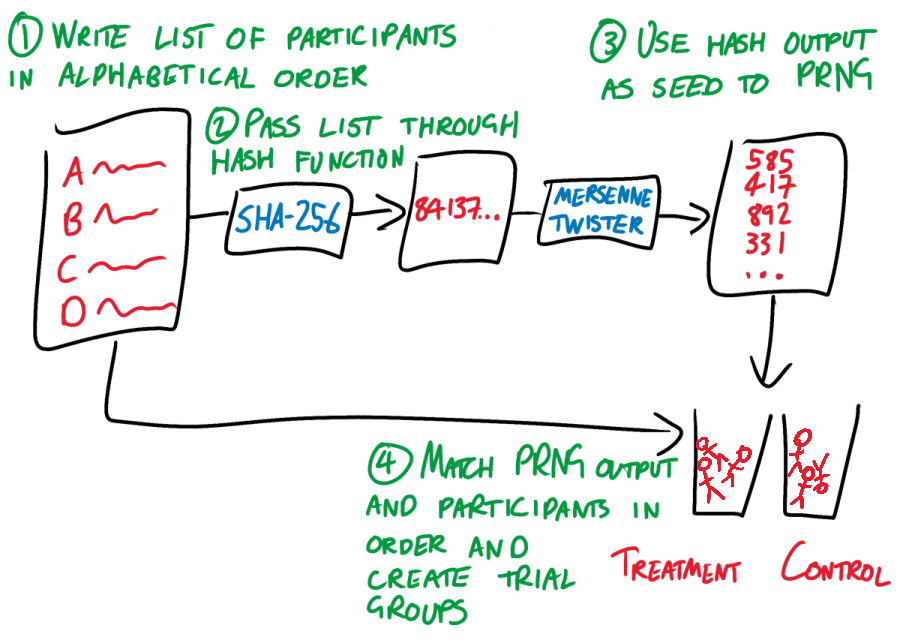

ROBERT goes as follows:

- The researcher takes their list of subjects (for example, village names) and arranges them in alphabetical order. Each name should be on a new line.

- The researcher uses a hash function to chaotically but deterministically convert this list to a single integer. It doesn’t matter which hash function, so long as the RCT community all agrees on one and the researcher doesn’t get to choose. Let’s choose SHA-256, unless someone has a better idea.

- The researcher takes the output of this hash function, and uses it as the seed for a pseudo-random number generator (PRNG). Once again, it doesn’t matter which PRNG, so long as everyone uses the same one. A Mersenne Twister should be fine.

- The researcher pulls numbers from the Mersenne Twister and assigns them to participants in alphabetical order. The number that a participant is assigned determines which trial group they are placed in. For the vanilla case of one control and one treatment group, let’s say that an odd number means that a participant goes in the control group, while an even number means that they go in the treatment group. Yet again, the exact process does not matter, so long as it is fixed.

ROBERT works by rigidly and prescriptively taking choices away from the researcher, and by linking every step of the randomization process to every other step. The only choice that the researcher gets to make is in their list of trial participants. This list leads, chaotically but entirely deterministically, to a trial group assignment. If the researcher tries to fiddle with their list of participants so that it “better” fits the resulting assignment, then the assignment changes. Change anything, change everything.

ROBERT is replicable. An external observer can re-run the randomization process. This allows them to verify that the resulting group assignments were produced programmatically, not by hand. ROBERT uses “pseudo-randomness” - output that looks wild and random, but is in fact generated deterministically from an initial “seed” value. Running the same PRNG with the same seed with always produce the same output, making ROBERT replicable.

Since the output of a PRNG is determined entirely by its seed, this seed is a potential researcher degree of freedom. If we allowed our researcher to control their PRNG seed, they could keep cycling through values until they found an output and set of assignments that they liked. When asked “why did you use 816101298 as your seed?” they could reply “it’s my lucky number”, and who’s to say that they’re lying? Everything is still perfectly random, for a bad definition of the word “random”.

We therefore have to take the choice of seed away from the researcher. A simple option would be to always use the seed 1. However, this would mean that the researcher would know the assignments that they were going to be dishing out to their alphabetically-ordered participants before they had recruited those participants. This would allow them to recruit a well-designed sequence of promising and hopeless participants, with perfectly ordered names that resulted in a disastrously lop-sided group assignment. Even if flawlessly sculpting the entire participant list proved unfeasible, there would still plenty of room for small-scale sneakiness. If you knew that the first village in your list was going to be assigned to your treatment group, would you put much effort into recruiting the struggling, disease-stricken village of Aaaaaville?

This is why step 2 of ROBERT requires the researcher to generate their seed from the names of their trial participants. Now every time the dataset changes, so does the seed. And when the seed changes, so does the PRNG output, and so does the entire group assignment. The researcher has no idea whether Aaaaavile will end up in the treatment or the control, and so has no idea whether they should recruit them or not. This is as it should be.

Finally, ROBERT specifies the way in which the researcher is allowed to turn their pseudo-random sequence into trial groups. It doesn’t matter whether PRNG output is matched to participants in alphabetical order, reverse alphabetical order, or reverse alphabetical order by second letter starting from the letter K. All that matters is that there is a single, standard way, and that our researcher doesn’t get to make any choices.

How good is ROBERT?

ROBERT goes a long way, but doesn’t fully prevent malfeasance. A researcher could engineer re-rolls of the dice by experimenting with alternative spellings of their participants. Should it be written DRC, D.R.C., or Democratic Republic of the Congo? The solution is further standardization wherever possible. Maybe researchers should be required to use a location’s name exactly as it is spelled by the national government’s tax records, or by some kind of UN database, or by Google Maps.

Even more nefariously, a researcher could take the full set of participants who have agreed to participate in their study, and see what happens to their group assignments when they add or remove different combinations of potential participants. They can keep adding and removing participants until they reach a suitably favorable assignment. This is a real risk. Nonetheless, ROBERT still drastically limits the number of re-rolls that they get. And if a participant joins or leaves the trial at the last moment, the researcher’s house of cards gets knocked down and re-randomized, and it’s a whole different ball game.

In conclusion

ROBERT allows researchers running RCTs to generate trustworthy, tamper-proof, replicable randomness. It is quick, easy, and requires no third-parties. It takes lessons learned from decades of hospital RCTs, and patches up many of the vulnerabilities through which well- and ill-meaning people have historically tried to subvert the power of randomness.

I’d argue that ROBERT is even backwards-compatible, and meets the Cochrane Collaboration’s current guidelines for acceptable RCT randomness. So if you’re running an RCT and need a replicable, trustworthy source of randomness, give ROBERT a go.

Here’s a simple script that implements a basic version of ROBERT. Pull requests welcomed.

All you need in order to run a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) is a few willing participants and a good source of randomness. With only these simple ingredients you can arbitrarily give half of your participants something that might be good; give the other nothing; and then watch and measure how things turn out. Your results are free from bias and confounding, thanks to the cleansing power of randomness.

This means that you’d better make sure that you get your randomness right. And to increase outside observer’s trust in your results, ideally you should be able to prove it. Lots of effort has therefore been put into making sure that hospital-based RCTs are shuffled properly. The result of this effort has been a wonderful combination of better science and entertaining stories of determined clinicians trying to cheat. Despite this, much less attention has been paid to RCTs run outside of hospitals.

Therefore, in this blog post I present the Randomize Optimally By Entirely Removing Trust (ROBERT) algorithm. Using some very mild cryptography, ROBERT allows researchers running non-hospital-based RCTs to generate trustworthy, replicable randomness. In this post I’ll describe why ROBERT is necessary, how it works, and how it can be improved.

Let’s begin our journey inside a hospital.

Hospital-based RCTs

Suppose that a researcher wants to test out a promising new cancer treatment. She decides to run an RCT with 100 cancer patients. She won’t begin her trial with all 100 participants fully enrolled and ready to go. Instead, she will have new patients referred to her over time, and she’ll gradually build up her trial population over several weeks or months. Whenever a new patient joins her trial, she’ll need to somehow assign them to either her control or treatment group.

Our researcher is probably torn between scientific truth and personal success. She does want to discover the reality of her new treatment, even if it doesn’t turn out to be the reality she was hoping for. But she also wants her photo to appear in medical textbooks with the caption “her father no longer questions her life choices”. This means that there’s a big part of our researcher that would quite like it if she got to choose how patients were assigned to the control and treatment groups. She could put all the promising patients in the treatment group, and all the desperate ones in the control. This would make for a positive result, but very bad science.

The whole point of an RCT is that control and treatment groups must be assigned at random. Generating a random assignment is a two-step process. First, our researcher must generate an unpredictable random sequence. Second, she must use her random sequence to randomly assign participants to trial groups. As we will see, even if a researcher generates a suitable sequence in step 1, she still has still an enormous amount of room for mistake and malfeasance in step 2.

Suppose that our researcher somehow knew that the next patient who enrolled in her study was going to be assigned to the treatment group. Our researcher might stop accepting sickly-looking patients, and start seeking out more sprightly-seeming ones instead. Our researcher need not exert this influence overtly, or even deliberately. As Detorri (2010) speculates:

Perhaps the patient hesitates briefly when the study is mentioned and the surgeon suggests that the patient sleep on the idea of participating. Maybe the surgeon decides to get more tests before offering enrollment. The number of different subtle possibilities to exclude this patient is only limited by one’s imagination.

This means that upcoming trial group assignments should be treated as top-secret, radioactive information, accessible only on a need-to-know basis. However, this is often not the case. Sometimes assignments are kept insufficiently secure, and sometimes they are even helpfully posted on bulletin boards in hospital common rooms. Some trials hide upcoming assignments inside sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes, which may only be opened once a patient has been officially enrolled in the study. But sneaky researchers have been known to hold these envelopes in front of a light bulb to try and peek at the group assignment contained within. Schulz and Grimes (2002) even describe how one researcher took a particularly thick envelope to their hospital’s X-ray wing so that they could blast it with the department’s powerful backlights. Schulz and Grimes also describe how one clinician mounted a night-raid on a chief investigators’ office in search of a master copy of future group assignments. People can do unprofessional things when their ideas are on the line.

There are two options available to a noble-minded researcher who wants to assure their readers that their study is truly random. First, they could use a centralized, third-party randomness management service like SealedEnvelope. These services generate, record, and safeguard group assignments, and prevent the research team from meddling with them.

Alternatively, the researcher could try to implement a bulletproof system of physical sealed envelopes, capable of standing up to even the most determined inspection and skullduggery. Such systems can get very fiddly, often involving hidden carbon paper, and yet they’re still likely to be vulnerable to a determined attacker with a little imagination.

Whichever way you approach it, proper group assignment can feel like a lot of elaborate work just to replace what is fundamentally a coin flip. However, this work appears to be crucial: according to Schulz and Grimes (2002), trials with inadequate or unclear allocation concealment produce estimates of effect that are up to 40% higher than their properly run counterparts. This is no idle concern.

RCTs outside the hospital

Because of this, well-run hospital-based RCTs are now randomized using piles of paranoia and plenty of precise procedures. However, to the best of my knowledge, much less scrutiny is leveled at the randomization of RCTs run outside of hospitals. Suppose that a development economist wants to investigate the effect of a new type of malaria treatment across a trial population of 400 villages. He decides to run a “cluster-RCT”, in which he assigns entire villages - instead of individuals - to control and treatment groups.

Unlike our medical researcher, our development economist starts his trial with a full list of all participating villages. He can therefore perform all of his randomization and group-assignment simultaneously, at the beginning of his trial. To my suspicious mind, this is a wonderful opportunity for shenanigans.

The academic community appears to broadly agree. Researchers often describe and justify their randomization procedures in the write-ups of their trials. They compare their treatment and control groups across a range of baseline characteristics (eg. age, income, wealth, health, family size), hoping to prove that randomness has done its job and that their trial groups are suitably similar. The Cochrane Collaboration, an organization that reviews and analyses academic research, requires its reviewers to check that papers report a proper randomization process. Those that do not are downgraded.

This is all much better than nothing. I’m sure that Doe et al are all very nice people once you get to know them. I can see that Doe generated his trial groups using “computer randomness”, and I agree that his tests of baseline balance all check out. But I still see a significant gap between claim and proof, which can only be crossed by trust. Trust is a flimsy material with which to build a bridge, and should only be used when no other alternative is available.

For example, how do I know that our researcher didn’t carefully “randomize” his groups so that they were balanced on all of the characteristics in his baseline balance tests, but extremely (or even just mildly) one-sided on some other, unobserved characteristics? I assume that he didn’t. But whenever you assume you make an “as” out of “sum” and “e”. It seems odd to me that we trust our development economist to generate his own randomness and group assignments, even though we know that medical researchers are perfectly willing to X-ray envelopes and ransack offices in order to try to influence theirs.

One way in which our researcher could partially increase my trust in him is through a public lottery. Our researcher could find a reputable person, perhaps someone from their trial participants’ community. Our researcher could have this person publicly draw names out of a hat, and use the results to assign treatment and control groups. This type of public lottery is definitely better and harder to fiddle with than a private spreadsheet. But as a post-hoc observer, I still can’t audit whether our researcher performed the lottery correctly, or even whether he performed it at all.

Our researcher could use the blockchain somehow. No, seriously - it would be hard to understand and easy to make fun of, but it would probably work. Or they could copy hospital RCT best practices, and contract their randomness out to an auditable third-party. But both of these approaches would add complexity. What if the third-party goes out of business? What if they get hacked? What if I, as an outside observer, am congenitally incapable of trusting anyone?

The solution: ROBERT

The solution is the Randomize Optimally By Entirely Removing Trust (ROBERT) algorithm. Using the ROBERT algorithm, our researcher can produce trial group assignments that are:

- Random - the basic criteria for a random assignment

- Replicable - an outside observer can rerun the algorithm and produce the same results. This means that they can verify that the assignment really was generated programmatically, and not by hand.

- Tamper-resistant - an outisde observer can be confident that, within certain parameters, the researcher has not tampered with the assignments by, for example, regenerating assignments until they find one that they like.

- Not reliant on any third-parties - there’s no need for researchers or observers to trust or talk to anyone. Assignment groups can be generated and verified without even an internet connection.

ROBERT achieves these properties by restricting our researcher’s randomization choices - or “degrees of freedom” - as much as possible. All the researcher gets to choose is their list of trial participants, and ROBERT deterministically turns this list into a single, verifiable group assignment. Because after all, what are choices but an opportunity to fiddle with your RCT?

ROBERT goes as follows:

- The researcher takes their list of subjects (for example, village names) and arranges them in alphabetical order. Each name should be on a new line.

- The researcher uses a hash function to chaotically but deterministically convert this list to a single integer. It doesn’t matter which hash function, so long as the RCT community all agrees on one and the researcher doesn’t get to choose. Let’s choose SHA-256, unless someone has a better idea.

- The researcher takes the output of this hash function, and uses it as the seed for a pseudo-random number generator (PRNG). Once again, it doesn’t matter which PRNG, so long as everyone uses the same one. A Mersenne Twister should be fine.

- The researcher pulls numbers from the Mersenne Twister and assigns them to participants in alphabetical order. The number that a participant is assigned determines which trial group they are placed in. For the vanilla case of one control and one treatment group, let’s say that an odd number means that a participant goes in the control group, while an even number means that they go in the treatment group. Yet again, the exact process does not matter, so long as it is fixed.

ROBERT works by rigidly and prescriptively taking choices away from the researcher, and by linking every step of the randomization process to every other step. The only choice that the researcher gets to make is in their list of trial participants. This list leads, chaotically but entirely deterministically, to a trial group assignment. If the researcher tries to fiddle with their list of participants so that it “better” fits the resulting assignment, then the assignment changes. Change anything, change everything.

ROBERT is replicable. An external observer can re-run the randomization process. This allows them to verify that the resulting group assignments were produced programmatically, not by hand. ROBERT uses “pseudo-randomness” - output that looks wild and random, but is in fact generated deterministically from an initial “seed” value. Running the same PRNG with the same seed with always produce the same output, making ROBERT replicable.

Since the output of a PRNG is determined entirely by its seed, this seed is a potential researcher degree of freedom. If we allowed our researcher to control their PRNG seed, they could keep cycling through values until they found an output and set of assignments that they liked. When asked “why did you use 816101298 as your seed?” they could reply “it’s my lucky number”, and who’s to say that they’re lying? Everything is still perfectly random, for a bad definition of the word “random”.

We therefore have to take the choice of seed away from the researcher. A simple option would be to always use the seed 1. However, this would mean that the researcher would know the assignments that they were going to be dishing out to their alphabetically-ordered participants before they had recruited those participants. This would allow them to recruit a well-designed sequence of promising and hopeless participants, with perfectly ordered names that resulted in a disastrously lop-sided group assignment. Even if flawlessly sculpting the entire participant list proved unfeasible, there would still plenty of room for small-scale sneakiness. If you knew that the first village in your list was going to be assigned to your treatment group, would you put much effort into recruiting the struggling, disease-stricken village of Aaaaaville?

This is why step 2 of ROBERT requires the researcher to generate their seed from the names of their trial participants. Now every time the dataset changes, so does the seed. And when the seed changes, so does the PRNG output, and so does the entire group assignment. The researcher has no idea whether Aaaaavile will end up in the treatment or the control, and so has no idea whether they should recruit them or not. This is as it should be.

Finally, ROBERT specifies the way in which the researcher is allowed to turn their pseudo-random sequence into trial groups. It doesn’t matter whether PRNG output is matched to participants in alphabetical order, reverse alphabetical order, or reverse alphabetical order by second letter starting from the letter K. All that matters is that there is a single, standard way, and that our researcher doesn’t get to make any choices.

How good is ROBERT?

ROBERT goes a long way, but doesn’t fully prevent malfeasance. A researcher could engineer re-rolls of the dice by experimenting with alternative spellings of their participants. Should it be written DRC, D.R.C., or Democratic Republic of the Congo? The solution is further standardization wherever possible. Maybe researchers should be required to use a location’s name exactly as it is spelled by the national government’s tax records, or by some kind of UN database, or by Google Maps.

Even more nefariously, a researcher could take the full set of participants who have agreed to participate in their study, and see what happens to their group assignments when they add or remove different combinations of potential participants. They can keep adding and removing participants until they reach a suitably favorable assignment. This is a real risk. Nonetheless, ROBERT still drastically limits the number of re-rolls that they get. And if a participant joins or leaves the trial at the last moment, the researcher’s house of cards gets knocked down and re-randomized, and it’s a whole different ball game.

In conclusion

ROBERT allows researchers running RCTs to generate trustworthy, tamper-proof, replicable randomness. It is quick, easy, and requires no third-parties. It takes lessons learned from decades of hospital RCTs, and patches up many of the vulnerabilities through which well- and ill-meaning people have historically tried to subvert the power of randomness.

I’d argue that ROBERT is even backwards-compatible, and meets the Cochrane Collaboration’s current guidelines for acceptable RCT randomness. So if you’re running an RCT and need a replicable, trustworthy source of randomness, give ROBERT a go.

Here’s a simple script that implements a basic version of ROBERT. Pull requests welcomed.