Preventing impossible game levels using cryptography

22 Jul 2020

You and your good buddy, Steve Steveington, have almost finished work on your company’s new video game. It’s a banal 2-D platformer in which you run from left to right and collect coins or rings or some other kind of doodad. At the end you rescue a Princess or save a city or whatever, who cares, the player has already given you their money and you don’t do refunds.

You’ve been creating your mediocrepiece in your offices in the 19th Century Literature section of the San Francisco Public Library, the same birthplace as all your previous companies (start here and work forwards to catch up). The library is currently closed to the general public because of the Covid-19 pandemic, but you’ve reached an understanding with the security guard whereby he doesn’t try to be a hero and you stop being mean about him on Twitter.

With the game almost finished, you had been working hard on crafting your email spam campaigns. But then, out of nowhere, you were struck by an interesting disaster. Your pesky and valued colleagues, Kate Kateberry and Otekah Wrigglesworth, noticed a grave flaw in your game’s security model. Now your fragile ego and the life of Stevesoft, your fledgling company, both depend on whether you’re able to solve it.

The root cause of the flaw is that Stevesoft is a bootstrapped company on a shoe-string budget. This means that you don’t have any money to pay for level designers. You also don’t have any money to pay for core engine programmers, but you’ve reached an understanding with Kate and Otekah whereby they provide you with mediocre code and stale water-cooler banter and you don’t say anything about anything to the IRS. You think it was John le Carre who said that blackmail is more effective than bribery; he forgot that it’s also much cheaper.

To get around your lack of level designers you’ve decided to centre your game around user-generated levels, built by your players using an in-game level editor in the style of Little Big Planet and Super Mario Maker. This saves precious money and means that if your players don’t have fun then it’s their own stupid fault.

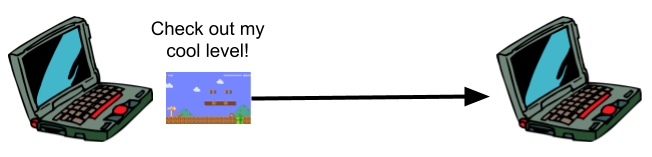

You don’t want players to have to share levels via a centralized server. Instead, you want them to be able to email level files to each other This retro mode of discovery makes you nostalgic for the days when you shared Nintendo cartridges with your friends and hadn’t yet been so thoroughly corrupted by a futile lust for fame and money and internet points. It’s also substantially cheaper than running a centralized server.

You have incredibly low standards and expectations for the levels produced by your community, and the only quality control you want to inject is that every user-created level must be guaranteed to be completable. You don’t want anyone stuck in a world where the only exit is the other side of an inoperable door. You have no qualms about selling turds to rubes who don’t read Steam reviews, but your shriveled conscience does still require that the turds be technically functional.

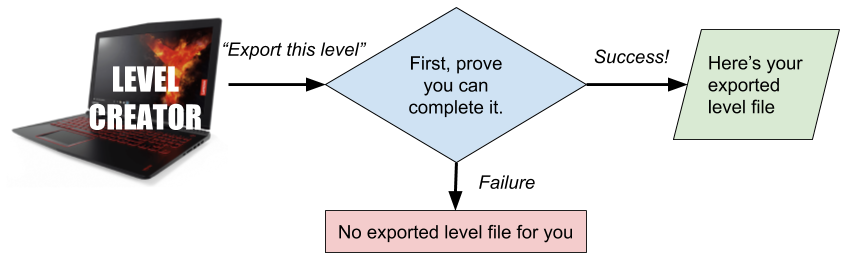

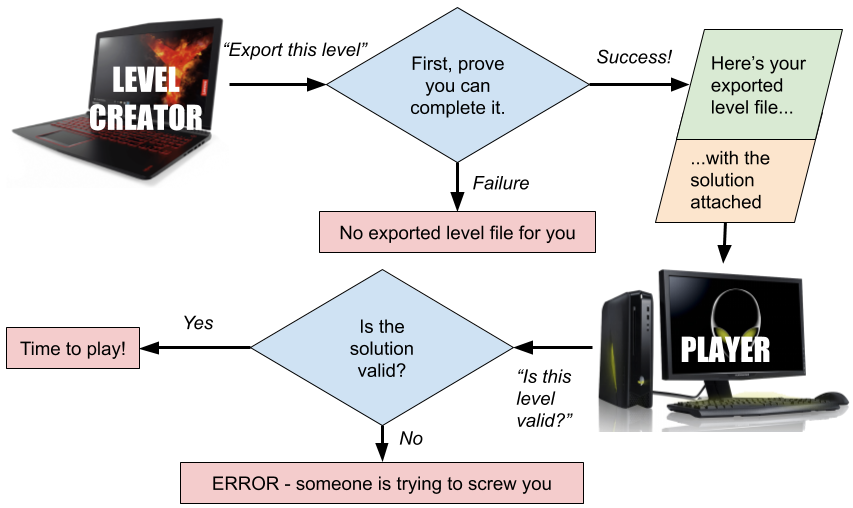

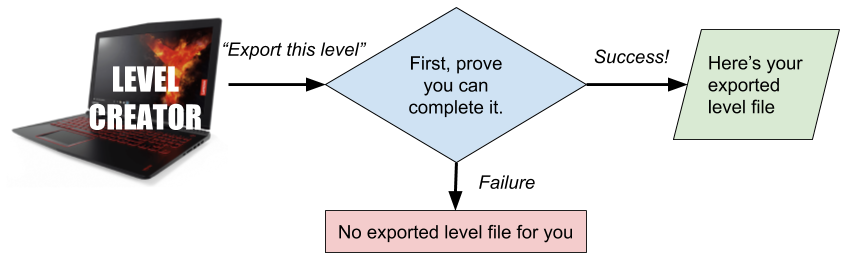

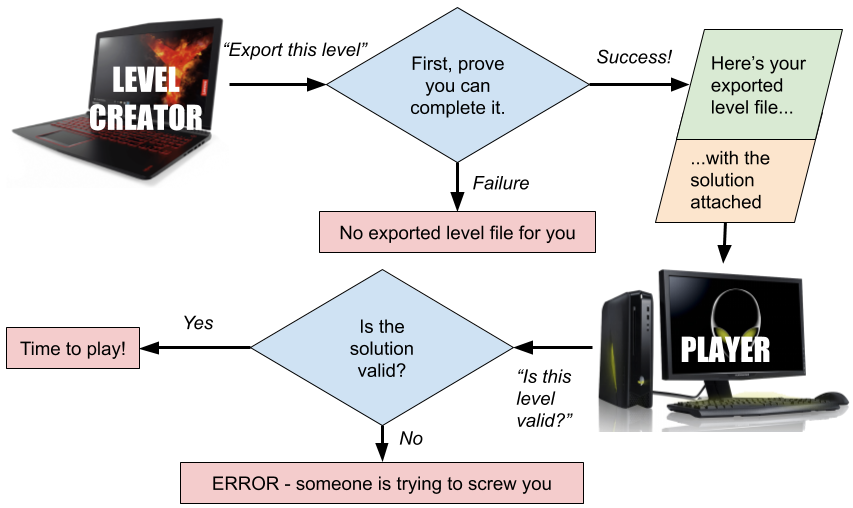

Your co-CEO, Steve Steveington, came up with a seemingly sensible idea for ensuring that every level is solvable. In his plan, players design their levels in the game’s level editor, and when they go to export their level to a file so that they can email it to their friends, the editor demands that they first demonstrate that they can complete the level themselves. Only once the level’s creator has passed their own challenge will the editor agree to save it to a file. Clever, no?

No.

The day starts innocuously with your team standup. As per usual, each person delivers their updates in the form of a disorganized ramble while the rest of the team browses Reddit. However, today Kate Kateberry’s laptop has run out of battery and her phone is recovering in a bowl of rice from a recent trip into the toilet. She finds herself with no choice but to listen to what her teammates have been working on.

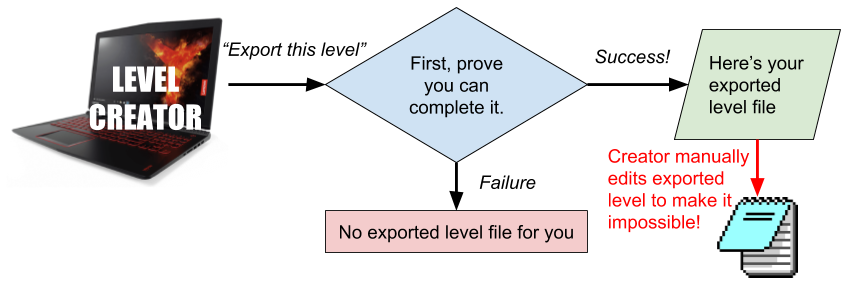

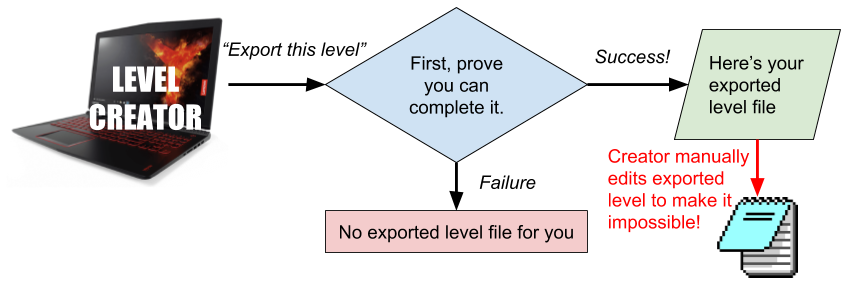

She listens as Steve describes his brilliant idea for preventing players from creating impossible levels. Once he has finished congratulating himself, she points out that his plan won’t work. Sure, it will prevent level creators from creating unsolvable levels using the in-game level editor. However, they can still manually edit the contents of an exported file in a standard text editor, resulting in potentially impossible levels. Worse, they can reverse engineer the entire structure of your level files, allowing them to build their own bootleg level editor that doesn’t require any proof that a level is solvable before it will export it. The output files from knockoff editors will be indistinguishable from those outputted by the game’s official editor. Unsuspecting players will have no idea that the game’s flimsy integrity protections had been bypassed, and may end up smashing their heads against an unsmashable wall.

As Kate gets more animated and Steve gets more grumpy, you and Otekah put your Reddit tabs to one side and join the ruckus. Would anyone really reverse engineer our entire file format just to mess with our game? you ask. Have you met anyone on the internet? Otekah replies.

Tensions rise; no progress is made; tempers flare; tempus fugit. Lunchtime comes and goes; blood sugar levels wax and wane and wane and wane. In age-old Stevesoft tradition you agree to hash things out in the Systems Design Thunderdome, a safe space in which combatants can hurl prejudices and ad hominems without fear of retribution from HR.

You, Steve, Kate and Otekah sit down to battle.

1. Can we include the level solution in the file?

Steve is the first to suggest a new way to prevent level creators from creating impossible levels. He suggests that when the level editor exports a level to a file, the file should include not just the level, but also its solution. The solution should be represented by the list of button presses that the level’s creator used to prove its solvability. When a player loads a level, the game tests out the solution attached to the level file in the background. If the solution is valid, it loads the level. If it is not, it warns the player that someone is trying to hoodwink them and exits.

Kate and Otekah agree that this would prevent level creators from luring players into impossible levels. However, this security would come at the cost of revealing the level’s solution to prospective players. Players could reverse engineer the format of the level files, extract the solution, and ruin the challenge. You all agree that this would be unacceptable, and you refine your requirements. Level creators mustn’t be able to share impossible levels, but level players mustn’t be able to cheat and read the solution from a level file either.

2. Can we encrypt the solution?

You’re up next. Everyone should take a step back, you say, since the answer is obvious and you can’t believe no one else has thought of it. All you need to do is have the level editor encrypt the solution before inserting it into the exported level file. When a player loads the level, the game decrypts the solution and runs it through the level, as Steve just suggested.

Otekah agrees that this sounds like a good solution, IF YOU’RE AN IDIOT. “Encryption” isn’t magic. Since the game is running on the player’s computer, anything the game can do the player can do too. If the game can decrypt the solution, the player can too. If the game contains the decryption key for the solutions, the player can pull the game apart, find the key, figure out the decryption steps that the game performs, and run these steps themselves. You can obfuscate your code and try to hide your keys and generally make life awkward for the player, but you can’t make decryption impossible. Eventually you run into the problem that people on the internet are psychotic monsters who will break anything and everything that they are mathematically able to.

You sulkily concede that Otekah is correct but note that she hasn’t exactly been helping.

3. Can we use zero-knowledge proofs?

Otekah harrumphs. Fine, she says. Maybe we can use zero-knowledge proofs. They’re pretty advanced, I bet that none of you have…

Kate cuts her off with a scoff. I think we all know that a zero knowledge proof is a way of proving to another person that you know a solution to a problem, without revealing what your solution actually is. I even wrote a short story about them once. But zero knowledge proofs only exist for very specific types of problem, like finding Hamiltonian cycles in large graphs. We, on the other hand, are making a criminally lazy 2-D platformer. Unless we want to throw away weeks of hard, half-arsed work and pivot our game to being “given a value y, a large prime p and a generator g, can you find a value x such that g**x mod p = y?”, we won’t be able to use zero knowledge proofs.

Otekah blows a raspberry.

4. Can we use AI?

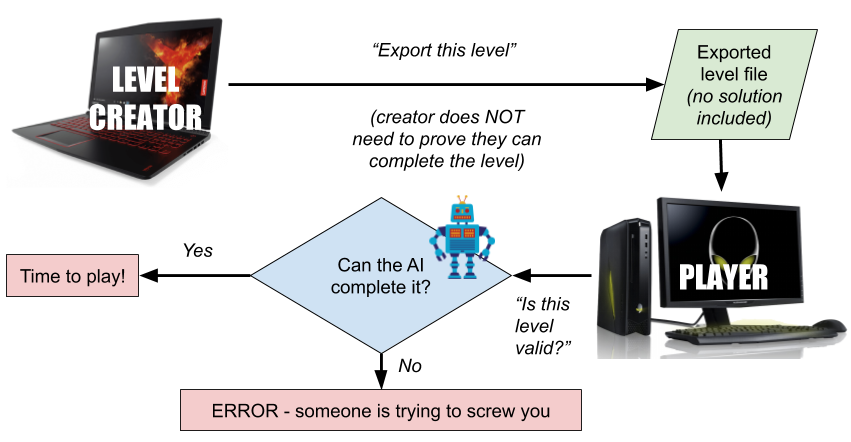

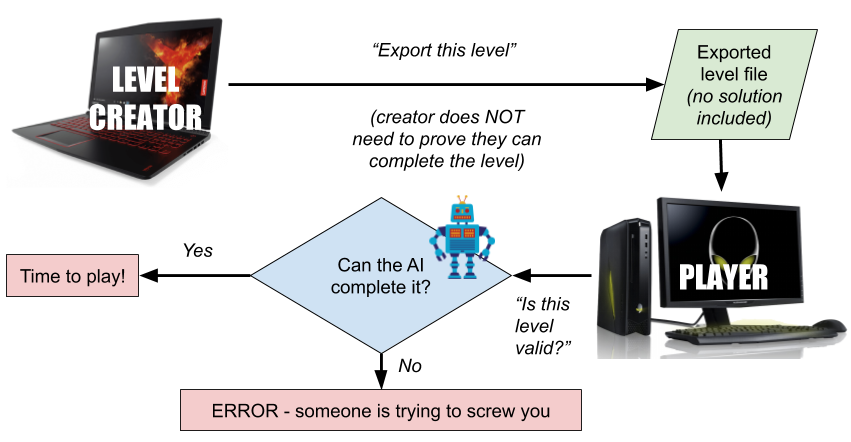

Let’s just use AI, says Steve. Everyone groans and throws books at him. The large print copy of A Brief History of Time that you keep on hand for this sort of thing catches him on the temple and he crumples like a coke can. Obviously we can’t use AI, you shout at his body. Presumably you were thinking something boneheaded like having the AI try to complete a level before the game will load it. This way we can verify that the level is solvable, but without having to include a solution that players can read and steal.

Kate starts shouting too. There are so many problems with that. For one thing, who’s going to write this AI? You? Don’t make me laugh. We’d need our AI to be essentially perfect. Our game is shonky enough without it locking people out of valid levels because our AI is too crappy to figure out how to complete them. Even if we did somehow manage to write a perfect AI, it would probably be slow and take a lot of computing power to run. Sure, the game could remember which levels it had already proven a solution for so it didn’t have to repeat itself, but that initial proof would still probably take forever.

Steve opens an eye and mumbles a begrudging acceptance.

5. Can we store levels in a centralized database?

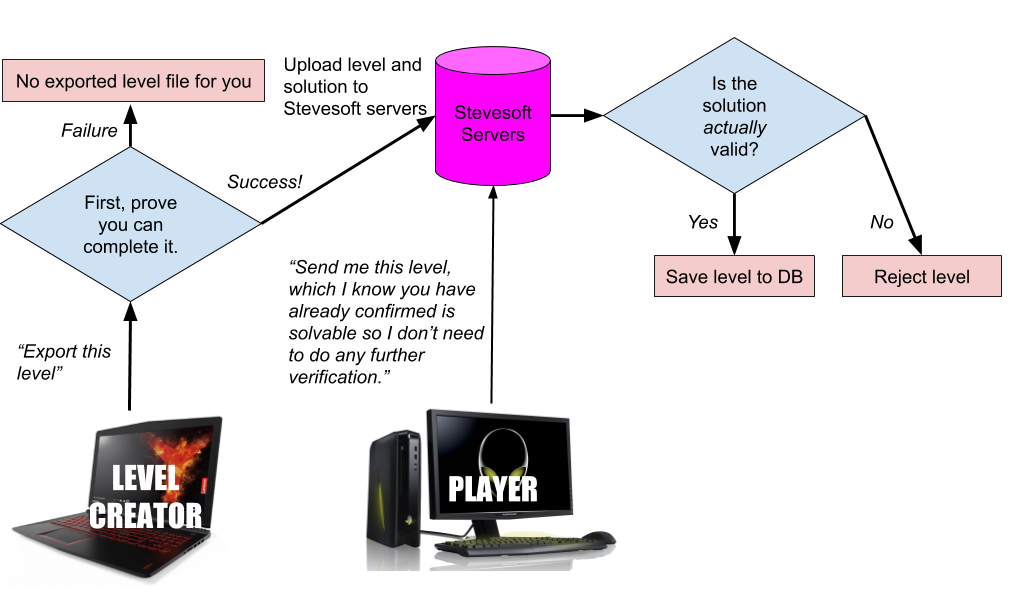

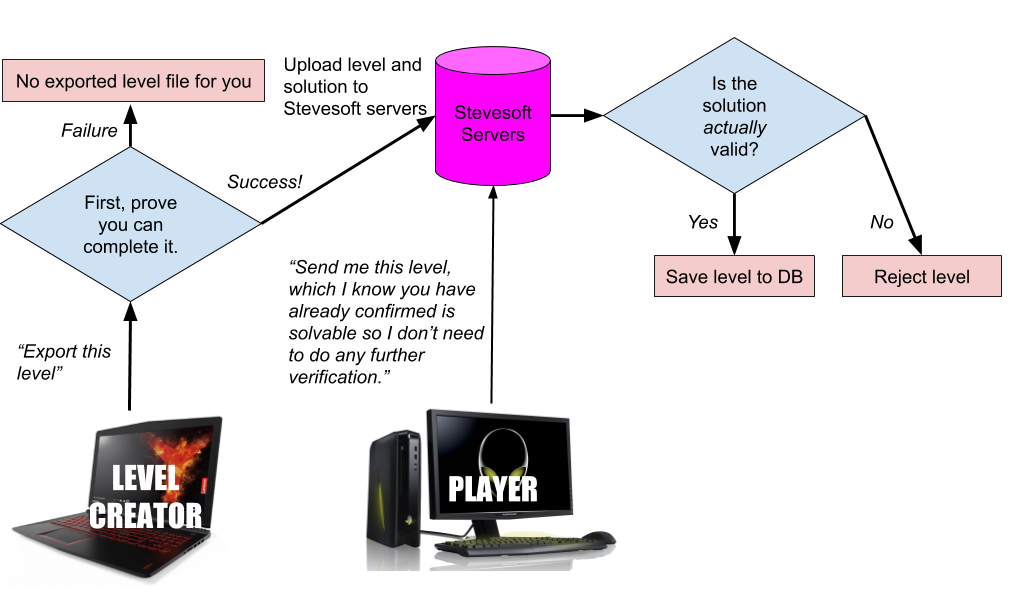

You have a brainwave. The team has been fixated on a model in which players send each other levels directly. Admittedly, this does have a righteous, retro feel to it that reminds you of a simpler, more morally defensible time. But what if you instead hosted all player-created levels in a centralized database? When a player creates a level, they prove that they can solve it. The level editor sends their level and their solution to the centralized Stevesoft server. The server plays through their solution, verifies that it does indeed complete the level, and saves the level to a database. Players can download levels from the server, safe in the knowledge that Stevesoft has verified that the level is completable. Even if a level creator builds a bootleg level editor that doesn’t force them to complete a level before it sends it to the server, the server would still validate their solution and block their level if it didn’t pass the mustard. As gravy on this already delicious cake, Stevesoft can use the central level index to collect and sell invasive personal data about its users.

Steve is just about awake from his textbook concussion. He agrees that this would be the most technically straightforward solution. However, since the company is funded by his mum’s credit card that she still hasn’t reported as stolen, he’s the closest thing that Stevesoft has to a CFO. He doesn’t want to have to pay to develop and deploy a whole jumble of database infrastructure. Cloud computing is quite cheap nowadays, but Stevesoft has very little money and it’s only a matter of time before his mum notices all the charges the gang have been racking up on her AmEx.

Steve concedes that the solution to the level integrity conundrum will likely require Stevesoft to run some servers of some sort, but he’d still like to keep them as cheap and lightweight as possible. Centralized servers that have to store and serve up every level that your players create will be too costly in both blood and treasure. Kate and Otekah agree. They couldn’t give two farts about Steve’s mum or her Amex, but they don’t want to have to sign up for any kind of Stevesoft Network Experience Center.

The Thunderdome continues.

6. Can we use public key cryptography? Take 1

What about public key encryption? says Kate. Steve says that she’ll need both to be more specific and to give a quick refresher in public-key cryptography, for the benefit of the others. Kate obliges, patronizingly. Let’s start from the top, with some definitions.

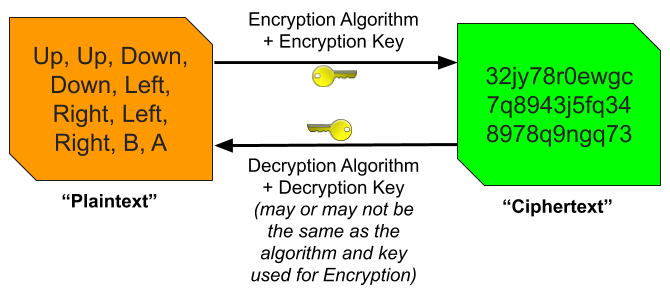

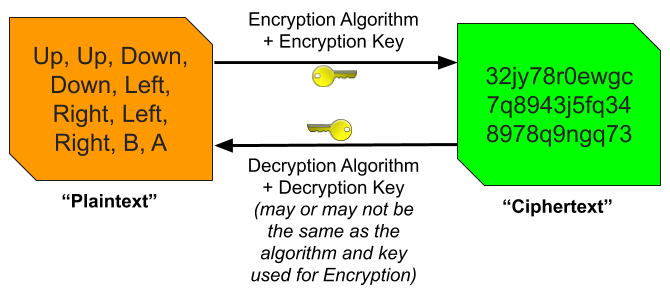

An encryption algorithm is a method of scrambling data. For example, in simple alphabet-rotation (or Caesar Cipher) encryption, the algorithm is that every letter in a message is rotated forward in the alphabet by a fixed number of places. An encryption key is an additional, secret input into the algorithm that determines its output. In alphabet-rotation encryption, the key is the number of spaces that each letter should be shifted. In order to produce an encrypted message or turn it back into plaintext, you need the appropriate key.

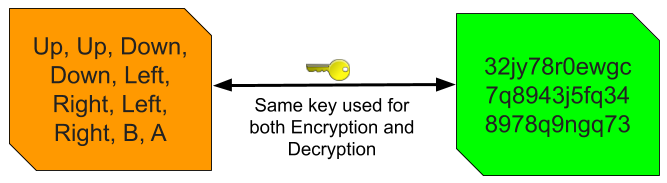

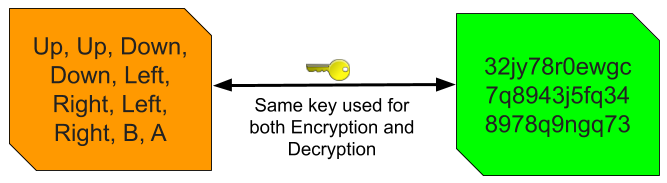

Before we talk about public key encryption, let’s talk about its much simpler opposite: symmetric key encryption. In symmetric key encryption the same key is used for both encrypting and decrypting a message. Alphabet-rotation encryption is symmetric; to encrypt a message you move each letter forward by a fixed amount, and to decrypt it you move each letter back by that same amount. If I want to send you message encrypted using symmetric key encryption then we need to agree on a shared key ahead of time. This type of encryption has its uses (such as in the post-key exchange phase of the TLS protocol), but I can’t think of any way to use it to solve our problem.

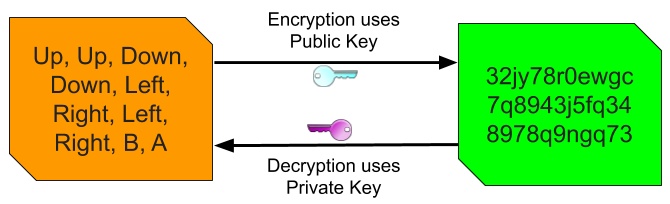

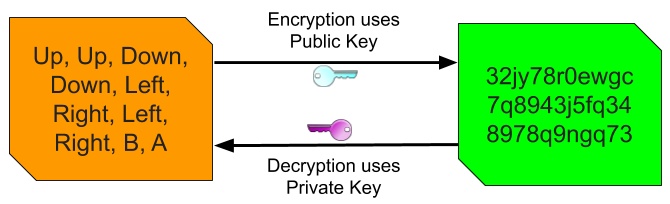

Public key cryptography is much more interesting, because different keys are used for encryption and decryption. An individual who wants to use public key cryptography starts by using another algorithm (the details of which aren’t important here) to generate two keys, known as a keypair. The most important property of this keypair is that a message encrypted by one key in the pair can only be decrypted by the other key. This means that neither key in the pair is able to decrypt a message that it itself encrypted. This might be tricky to wrap your head around, but the maths work out, I promise.

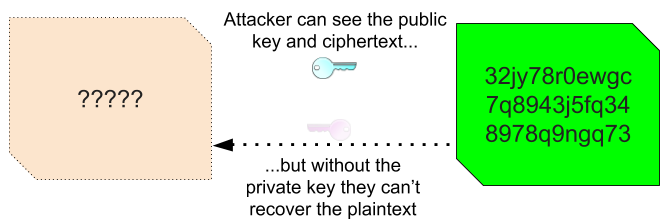

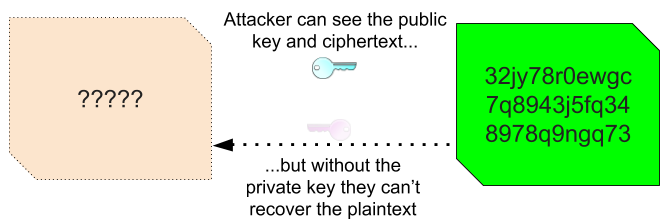

One key in the pair is designated as the public key, and the other as the private key. The public key is not at all sensitive. It can be published and distributed freely to anyone, even someone who the keys’ creator doesn’t trust. The private key is, of course, private, and so is kept secret. Now anyone who wants to send the keys’ creator a secret message should encrypt it using the creator’s published public key. Neither the sender nor the recipient needs to worry about the encrypted message being intercepted. An attacker could get their hands on both the encrypted message and the public key used to encrypt it. However, they would be unable to decrypt the message without the corresponding private key. So long as the private key remains truly private, messages encrypted with the public key remain truly secure.

Yes yes we all knew that, grumps Steve. How does any of it help us?

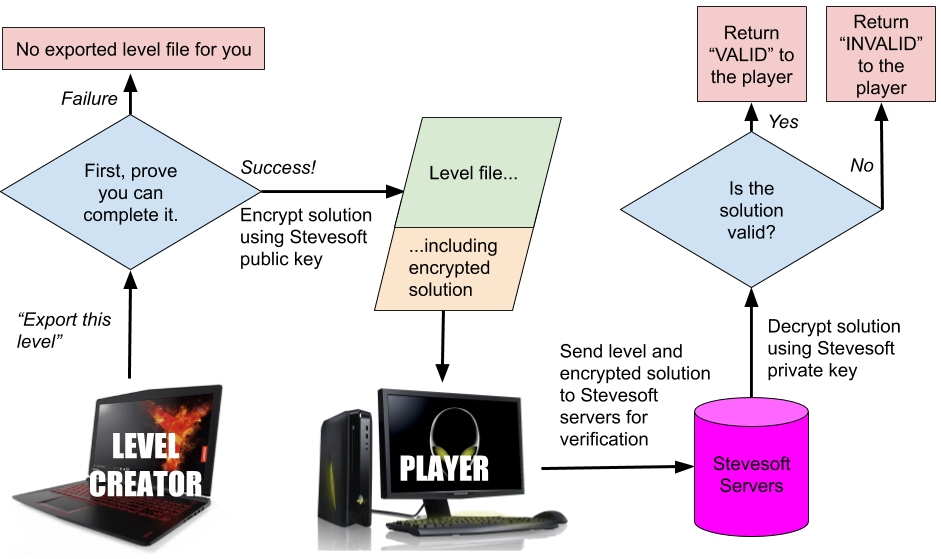

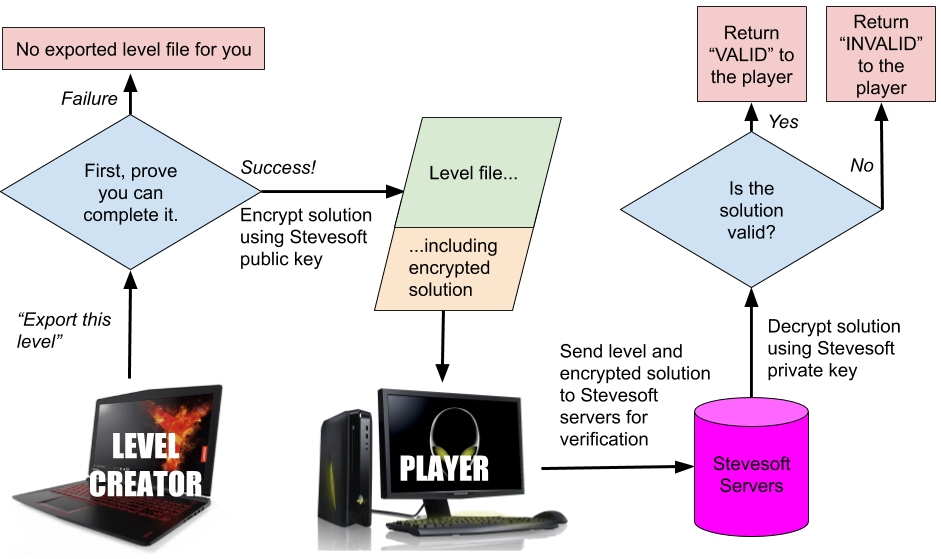

It helps us, says Kate, because it means that we can encrypt the solution to a level in a way that we can decrypt but our players can’t. This means that it’s safe for us to include the solution in our level files. To set this up, we generate a public/private keypair and package the public key with our game. When a level creator creates a level, they demonstrate a solution to it. The level editor records this solution; encrypts it using our public key; and includes the encrypted solution in the level file that it exports. The creator emails the file to their friends to play. The level file still includes a solution, but now it’s encrypted so players can’t access it. This is good.

However, if players can’t access the solution, this means that our game can’t either. This in turn means that the game can’t play through the level to check whether the solution is valid. To get round this, the game sends both the level and the solution over the internet to a server run by Stevesoft…

…then the server decrypts the solution, sends it back to the game, and the game validates it! I’d been thinking of something like that! you say, feigning support and making a grab for some of the credit.

Kate sighs. No, doofus, she says. If we did that then the player could just send us the encrypted solution themselves, pretending to be a copy of the game. We’d send them back the decrypted solution, then they could use it to cheat their way through the level again. Instead, we need to have our server decrypt the solution (using our private key), then, still on the server, run the solution through the level to check if it’s valid. Finally, the server sends a response back to the game saying whether the encrypted solution was valid or not, but containing no information about what the solution actually was.

You try to claim that this is all what you meant, but no one believes you. You go back on the offensive, pointing out that it would be inefficient to force the Stevesoft server to play through the level every time someone wanted to play it. Instead, the game client should save the results of each verification it requests from Stevesoft so that it only has to verify each level once. Plus, the Stevesoft servers should save the results of their solution play-throughs and store them in a cache. Then if the servers are asked to verify a level and a solution that they’ve already seen, they can read the result out of the cache without having to play through it again.

Aren’t we just back at my centralized database solution? asks Otekah. There are some superficial similarities, you reply, but this approach has several key advantages. First, we don’t have to store the entire contents of each level in our database, because we’re only responsible for verifying levels, not distributing them. Storage is cheap, but Stevesoft is broke. Second, and most important, our server isn’t a critical, central repository of any persistent data. In your centralized database approach, if our server got wiped and we had to rebuild it from scratch, we’d lose all of our players’ levels and hard work. Obviously we should keep backups of our database and run multiple redundant copies and all of that dorky stuff, but I think we all know that none of us can be bothered. However, in the public key cryptography approach, our servers don’t need to be anything like as stable and reliable. In this world, if our servers get wiped then all we lose is our cache of levels that we’ve previously verified. This would be irritating, but all it would mean is that we have to re-run our verification the next time someone asked us to verify a level, instead of reading a previous calculated result straight out of our cache. None of the data that we store is critical.

7. Can we use public-key cryptography? Take 2

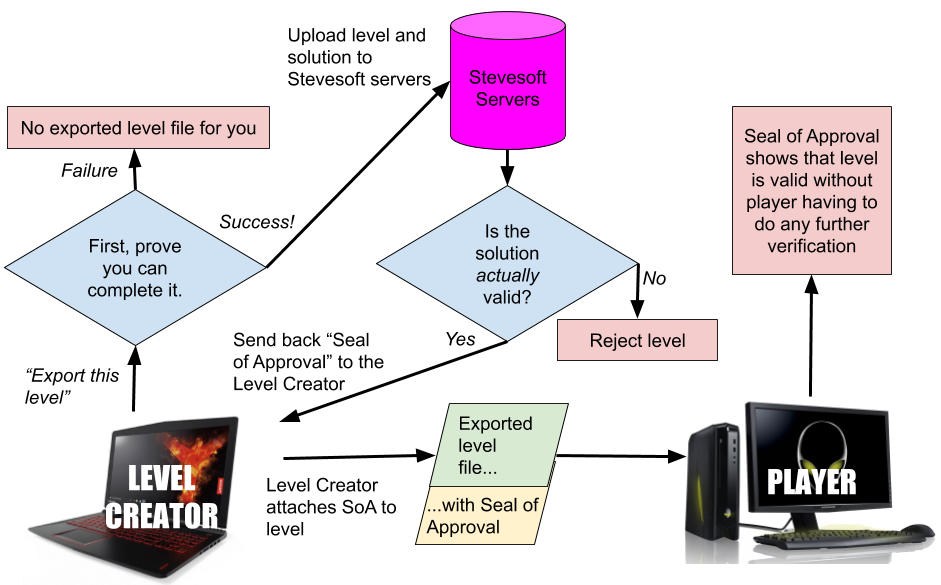

Otekah hems and haws then hurries to the whiteboard, which is actually just the library wall plus a pot of sharpies. What if, she says, we inverted this approach? Instead of validating a level’s solution when a player wants to play it, we instead validate it when a creator creates it.

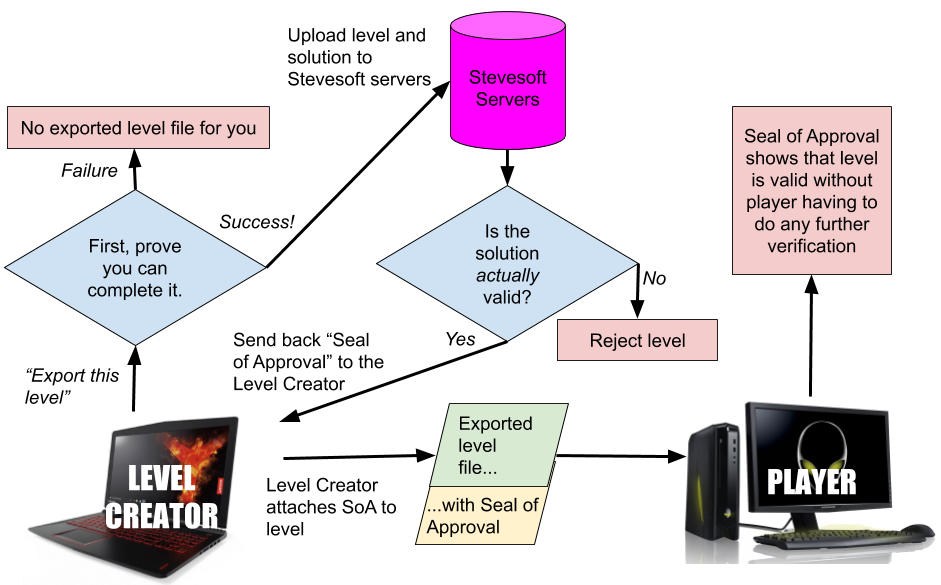

When a creator wants to export a level, they demonstrate a solution, as per usual. But this time the level editor immediately sends the level and its solution to the Stevesoft servers. The server plays through the solution. If it is valid, it sends the level creator back a cryptographic “seal of approval”, certifying that the level is solvable. The level editor exports the level, but instead of attaching the solution or an encrypted version of the solution, it attaches the seal of approval.

Finally, when a player loads a level, the game checks to see whether the level file contains a valid seal. If it does, the game knows that Stevesoft has played through the level and certified it to be solvable. If it does not, it rejects it. Everyone is safe; job done.

That sounds nice, says Steve. But how are you generating these magic seals of approval? Surely the noxious douchebags who play our game will figure out how to forge them too?

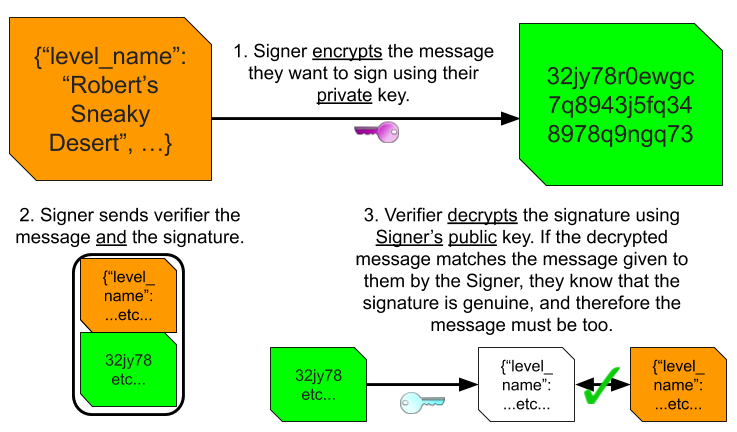

I was getting to that, says Otekah. The “seals of approval” aren’t made using magic; they’re made using cryptography. As you’ll recall, a keypair’s public and private keys are each able to decrypt messages encrypted by the other. When you want to send secret information to a recipient, as in the approach Kate was just describing, you encrypt it using their public key and they decrypt it using their private key.

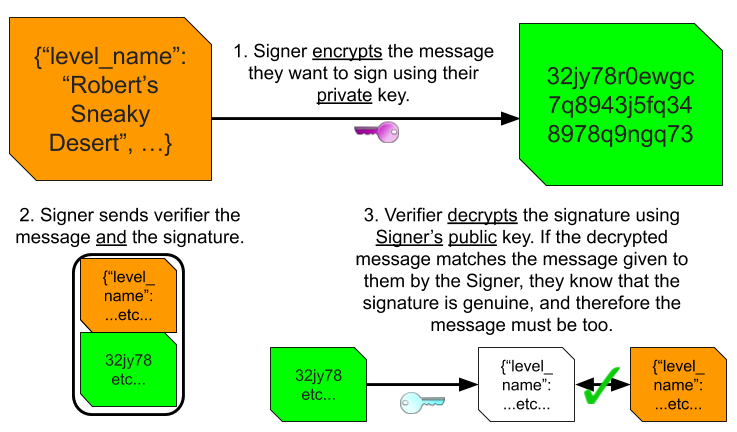

But public-key cryptography isn’t only useful for keeping information secret. It’s also useful for making information public, while ensuring that readers know that the information has been officially endorsed and approved by you. To do this you use the same encryption keys we just discussed to create a cryptographic signature.

First, you take the message that you want to approve and encrypt it using your private key. This encrypted text is the message’s cryptographic signature. Next, to prove to a recipient that you have approved the message, you send them both the message and its signature. Finally, the recipient can use your public key to decrypt the signature, and verify that the decrypted text matches the original message. This proves that the signature must have been originally created using your private key, which only you have access to. This means that the recipient can be confident that you were the creator of the signature, and that you approve the message.

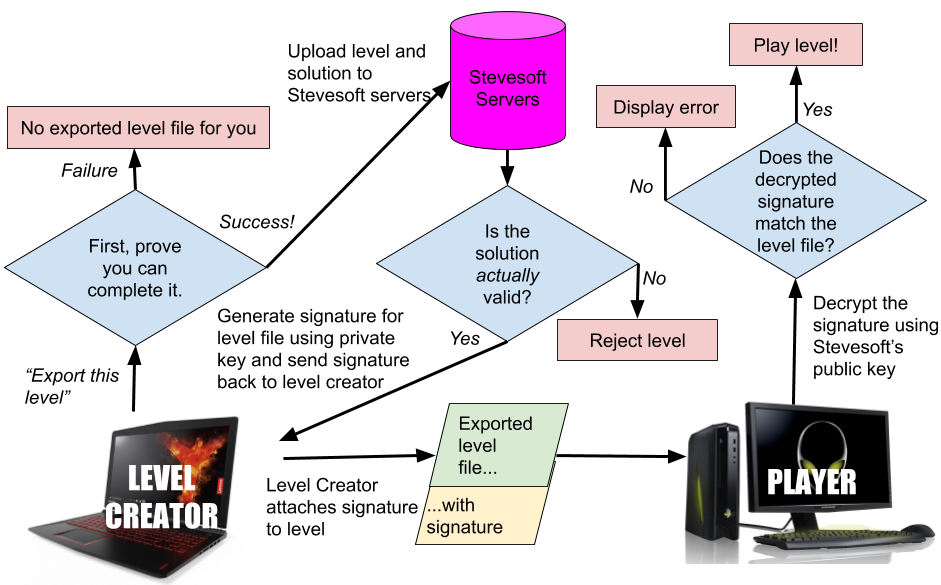

We can use this technique to generate cryptographic seals of approval for level files, once their creator proves to us that they can be solved. When a level creator wants to export a level, their level editor sends their level and solution to our server. Our server verifies that the given solution does indeed complete the level, and if it does, it uses our private key to sign the contents of the level and sends the signature back to the level creator. The creator’s level editor attaches the signature to the level file. When a player loads the level, their game uses the Stevesoft public key (bundled with the game) to decrypt the signature. If it matches the contents of the level file, the game knows that Stevesoft has verified that the level is solvable. Signatures can’t be forged, because they can only be generated using our private key, which only we have access to. Signatures can’t even be transferred from a valid level to an invalid one, because the decrypted signature has to match exactly the contents of the level.

I hear you snark - why is this any better than using our public key to encrypt the solution? Three reasons. First, it means that our server only ever has to verify a level once: when it’s created. Players don’t need our server in order to check whether a level’s signature is valid - all they need is our public key in order to validate the signature that we already generated. This means less load on our servers, and means we don’t even need to bother keeping a cache of verification results.

Second, it mitigates the consequences of our private key getting stolen. In the previous approach, anyone who hacked our systems and stole a copy of our private key would be able to use the key to decrypt the solution to any previously-published level. This would be a catastrophe. However, the second, signing approach doesn’t suffer from this problem. We don’t need to attach an encrypted copy of the solution to every level - all we need to attach is a harmless cryptographic signature.

That’s all true, says Kate, but I still think that my encryption approach is better. If our private key gets stolen then it’s undeniably annoying that players can cheat and get the solution to all levels, but at least we’ll still have the ability to tell non-cheating players whether a level has a solution or not. In your signing solution, if our private key gets stolen then the thief could use it to generate signatures for impossible levels. We would have to generate a new keypair; distribute its public key to all game clients; and start using that to sign all new levels instead. However, we would now have no idea whether any level signed with our old, compromised key was truly valid. Players have no way to tell the difference between valid levels that were legitimately signed by Stevesoft before the compromise, and invalid levels that were sneakily signed by an attacker after it. They’ll just have to play and hope that the level is valid.

Plus, it’s not necessarily true that your signing solution will cause less load on our servers than my encryption one. In my version, we have to make one validation request whenever a player wants to play a level for the first time. If 100 players want to play a level, we’ll make 100 validation requests, but if no one plays a level, we never need to validate it. In your solution, we always make 1 validation request for every level as soon as it’s created. If lots of levels get created but never played, your solution will cause more load on our servers.

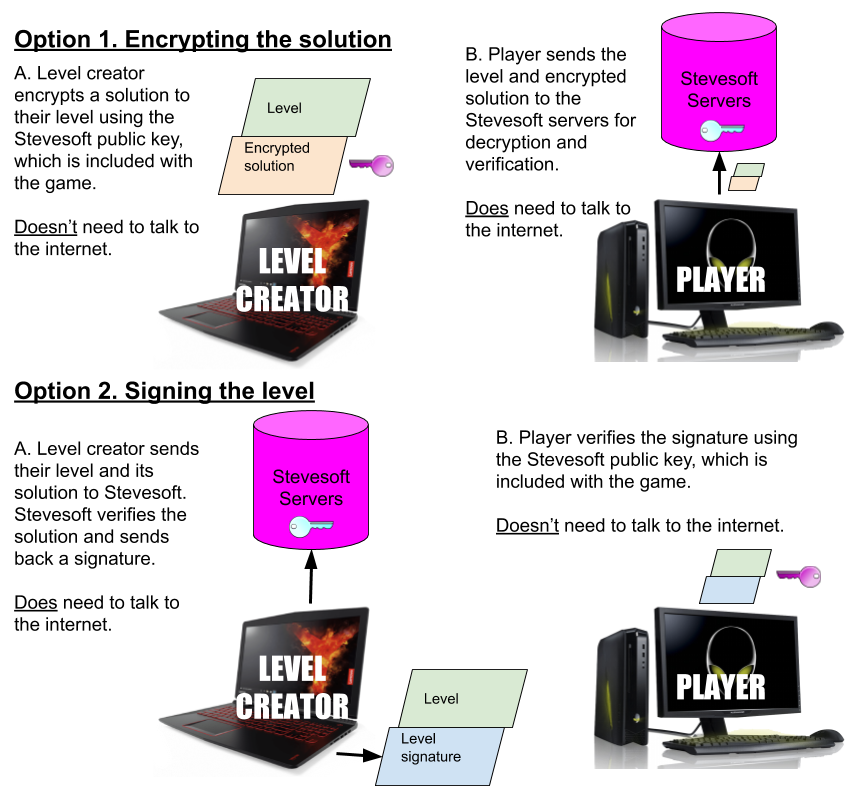

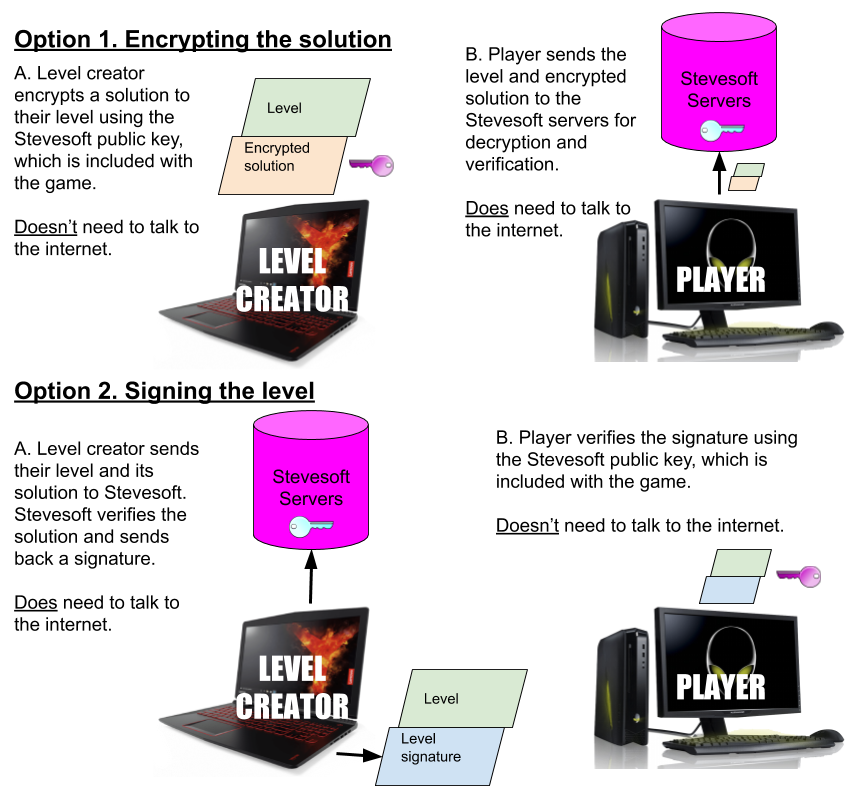

A final difference between our solutions is that my encryption solution allows level creators to create and export levels even when their internet isn’t working. This is because all they need in order to create a level file is our public key in order to encrypt their solution. However, my solution does require players to have an internet connection in order to play a level so that they can send it to our servers and we can validate the encrypted solution. Your solution is the opposite - creators need an internet connection when they want to export a level so that we can validate their solution and give them a signature, but players don’t need an internet connection in order to use our public key to validate this signature.

It’s dark outside. If the library were open it would have closed hours ago. The security guard comes up the stairs; you open Twitter and shake your phone at him, menacingly. He backs away.

So where does this all leave us? Kate asks. Silence.

This is all very clever, Otekah starts. But isn’t it a bit…much? We could keep going like this forever. We could allow third-parties to verify levels. We could develop an entire public key infrastructure to make our cryptography even more robust and flexible. These would all be fun projects to blackmail some interns into doing. But shouldn’t we just do the thing with the centralized database? If enough people upload enough levels to make the server bills expensive then surely we’ll have sold enough copies of the game to cover them?

Steve Steveington, sort-of-CFO, sighs. I suppose you’re right, he says. Can you put something together this week?

Well I don’t know…starts Otekah. Steve flaps a dossier of misfiled tax returns. Absolutely! she finishes.

Everyone packs up their stuff and leaves. You hang back. Don’t wait for me, you shout. No one waits for you. When you’re absolutely sure everyone has gone, you touch the drawings on the wall. You were a cryptographer, if only for a day.

You and your good buddy, Steve Steveington, have almost finished work on your company’s new video game. It’s a banal 2-D platformer in which you run from left to right and collect coins or rings or some other kind of doodad. At the end you rescue a Princess or save a city or whatever, who cares, the player has already given you their money and you don’t do refunds.

You’ve been creating your mediocrepiece in your offices in the 19th Century Literature section of the San Francisco Public Library, the same birthplace as all your previous companies (start here and work forwards to catch up). The library is currently closed to the general public because of the Covid-19 pandemic, but you’ve reached an understanding with the security guard whereby he doesn’t try to be a hero and you stop being mean about him on Twitter.

With the game almost finished, you had been working hard on crafting your email spam campaigns. But then, out of nowhere, you were struck by an interesting disaster. Your pesky and valued colleagues, Kate Kateberry and Otekah Wrigglesworth, noticed a grave flaw in your game’s security model. Now your fragile ego and the life of Stevesoft, your fledgling company, both depend on whether you’re able to solve it.

The root cause of the flaw is that Stevesoft is a bootstrapped company on a shoe-string budget. This means that you don’t have any money to pay for level designers. You also don’t have any money to pay for core engine programmers, but you’ve reached an understanding with Kate and Otekah whereby they provide you with mediocre code and stale water-cooler banter and you don’t say anything about anything to the IRS. You think it was John le Carre who said that blackmail is more effective than bribery; he forgot that it’s also much cheaper.

To get around your lack of level designers you’ve decided to centre your game around user-generated levels, built by your players using an in-game level editor in the style of Little Big Planet and Super Mario Maker. This saves precious money and means that if your players don’t have fun then it’s their own stupid fault.

You don’t want players to have to share levels via a centralized server. Instead, you want them to be able to email level files to each other This retro mode of discovery makes you nostalgic for the days when you shared Nintendo cartridges with your friends and hadn’t yet been so thoroughly corrupted by a futile lust for fame and money and internet points. It’s also substantially cheaper than running a centralized server.

You have incredibly low standards and expectations for the levels produced by your community, and the only quality control you want to inject is that every user-created level must be guaranteed to be completable. You don’t want anyone stuck in a world where the only exit is the other side of an inoperable door. You have no qualms about selling turds to rubes who don’t read Steam reviews, but your shriveled conscience does still require that the turds be technically functional.

Your co-CEO, Steve Steveington, came up with a seemingly sensible idea for ensuring that every level is solvable. In his plan, players design their levels in the game’s level editor, and when they go to export their level to a file so that they can email it to their friends, the editor demands that they first demonstrate that they can complete the level themselves. Only once the level’s creator has passed their own challenge will the editor agree to save it to a file. Clever, no?

No.

The day starts innocuously with your team standup. As per usual, each person delivers their updates in the form of a disorganized ramble while the rest of the team browses Reddit. However, today Kate Kateberry’s laptop has run out of battery and her phone is recovering in a bowl of rice from a recent trip into the toilet. She finds herself with no choice but to listen to what her teammates have been working on.

She listens as Steve describes his brilliant idea for preventing players from creating impossible levels. Once he has finished congratulating himself, she points out that his plan won’t work. Sure, it will prevent level creators from creating unsolvable levels using the in-game level editor. However, they can still manually edit the contents of an exported file in a standard text editor, resulting in potentially impossible levels. Worse, they can reverse engineer the entire structure of your level files, allowing them to build their own bootleg level editor that doesn’t require any proof that a level is solvable before it will export it. The output files from knockoff editors will be indistinguishable from those outputted by the game’s official editor. Unsuspecting players will have no idea that the game’s flimsy integrity protections had been bypassed, and may end up smashing their heads against an unsmashable wall.

As Kate gets more animated and Steve gets more grumpy, you and Otekah put your Reddit tabs to one side and join the ruckus. Would anyone really reverse engineer our entire file format just to mess with our game? you ask. Have you met anyone on the internet? Otekah replies.

Tensions rise; no progress is made; tempers flare; tempus fugit. Lunchtime comes and goes; blood sugar levels wax and wane and wane and wane. In age-old Stevesoft tradition you agree to hash things out in the Systems Design Thunderdome, a safe space in which combatants can hurl prejudices and ad hominems without fear of retribution from HR.

You, Steve, Kate and Otekah sit down to battle.

1. Can we include the level solution in the file?

Steve is the first to suggest a new way to prevent level creators from creating impossible levels. He suggests that when the level editor exports a level to a file, the file should include not just the level, but also its solution. The solution should be represented by the list of button presses that the level’s creator used to prove its solvability. When a player loads a level, the game tests out the solution attached to the level file in the background. If the solution is valid, it loads the level. If it is not, it warns the player that someone is trying to hoodwink them and exits.

Kate and Otekah agree that this would prevent level creators from luring players into impossible levels. However, this security would come at the cost of revealing the level’s solution to prospective players. Players could reverse engineer the format of the level files, extract the solution, and ruin the challenge. You all agree that this would be unacceptable, and you refine your requirements. Level creators mustn’t be able to share impossible levels, but level players mustn’t be able to cheat and read the solution from a level file either.

2. Can we encrypt the solution?

You’re up next. Everyone should take a step back, you say, since the answer is obvious and you can’t believe no one else has thought of it. All you need to do is have the level editor encrypt the solution before inserting it into the exported level file. When a player loads the level, the game decrypts the solution and runs it through the level, as Steve just suggested.

Otekah agrees that this sounds like a good solution, IF YOU’RE AN IDIOT. “Encryption” isn’t magic. Since the game is running on the player’s computer, anything the game can do the player can do too. If the game can decrypt the solution, the player can too. If the game contains the decryption key for the solutions, the player can pull the game apart, find the key, figure out the decryption steps that the game performs, and run these steps themselves. You can obfuscate your code and try to hide your keys and generally make life awkward for the player, but you can’t make decryption impossible. Eventually you run into the problem that people on the internet are psychotic monsters who will break anything and everything that they are mathematically able to.

You sulkily concede that Otekah is correct but note that she hasn’t exactly been helping.

3. Can we use zero-knowledge proofs?

Otekah harrumphs. Fine, she says. Maybe we can use zero-knowledge proofs. They’re pretty advanced, I bet that none of you have…

Kate cuts her off with a scoff. I think we all know that a zero knowledge proof is a way of proving to another person that you know a solution to a problem, without revealing what your solution actually is. I even wrote a short story about them once. But zero knowledge proofs only exist for very specific types of problem, like finding Hamiltonian cycles in large graphs. We, on the other hand, are making a criminally lazy 2-D platformer. Unless we want to throw away weeks of hard, half-arsed work and pivot our game to being “given a value y, a large prime p and a generator g, can you find a value x such that g**x mod p = y?”, we won’t be able to use zero knowledge proofs.

Otekah blows a raspberry.

4. Can we use AI?

Let’s just use AI, says Steve. Everyone groans and throws books at him. The large print copy of A Brief History of Time that you keep on hand for this sort of thing catches him on the temple and he crumples like a coke can. Obviously we can’t use AI, you shout at his body. Presumably you were thinking something boneheaded like having the AI try to complete a level before the game will load it. This way we can verify that the level is solvable, but without having to include a solution that players can read and steal.

Kate starts shouting too. There are so many problems with that. For one thing, who’s going to write this AI? You? Don’t make me laugh. We’d need our AI to be essentially perfect. Our game is shonky enough without it locking people out of valid levels because our AI is too crappy to figure out how to complete them. Even if we did somehow manage to write a perfect AI, it would probably be slow and take a lot of computing power to run. Sure, the game could remember which levels it had already proven a solution for so it didn’t have to repeat itself, but that initial proof would still probably take forever.

Steve opens an eye and mumbles a begrudging acceptance.

5. Can we store levels in a centralized database?

You have a brainwave. The team has been fixated on a model in which players send each other levels directly. Admittedly, this does have a righteous, retro feel to it that reminds you of a simpler, more morally defensible time. But what if you instead hosted all player-created levels in a centralized database? When a player creates a level, they prove that they can solve it. The level editor sends their level and their solution to the centralized Stevesoft server. The server plays through their solution, verifies that it does indeed complete the level, and saves the level to a database. Players can download levels from the server, safe in the knowledge that Stevesoft has verified that the level is completable. Even if a level creator builds a bootleg level editor that doesn’t force them to complete a level before it sends it to the server, the server would still validate their solution and block their level if it didn’t pass the mustard. As gravy on this already delicious cake, Stevesoft can use the central level index to collect and sell invasive personal data about its users.

Steve is just about awake from his textbook concussion. He agrees that this would be the most technically straightforward solution. However, since the company is funded by his mum’s credit card that she still hasn’t reported as stolen, he’s the closest thing that Stevesoft has to a CFO. He doesn’t want to have to pay to develop and deploy a whole jumble of database infrastructure. Cloud computing is quite cheap nowadays, but Stevesoft has very little money and it’s only a matter of time before his mum notices all the charges the gang have been racking up on her AmEx.

Steve concedes that the solution to the level integrity conundrum will likely require Stevesoft to run some servers of some sort, but he’d still like to keep them as cheap and lightweight as possible. Centralized servers that have to store and serve up every level that your players create will be too costly in both blood and treasure. Kate and Otekah agree. They couldn’t give two farts about Steve’s mum or her Amex, but they don’t want to have to sign up for any kind of Stevesoft Network Experience Center.

The Thunderdome continues.

6. Can we use public key cryptography? Take 1

What about public key encryption? says Kate. Steve says that she’ll need both to be more specific and to give a quick refresher in public-key cryptography, for the benefit of the others. Kate obliges, patronizingly. Let’s start from the top, with some definitions.

An encryption algorithm is a method of scrambling data. For example, in simple alphabet-rotation (or Caesar Cipher) encryption, the algorithm is that every letter in a message is rotated forward in the alphabet by a fixed number of places. An encryption key is an additional, secret input into the algorithm that determines its output. In alphabet-rotation encryption, the key is the number of spaces that each letter should be shifted. In order to produce an encrypted message or turn it back into plaintext, you need the appropriate key.

Before we talk about public key encryption, let’s talk about its much simpler opposite: symmetric key encryption. In symmetric key encryption the same key is used for both encrypting and decrypting a message. Alphabet-rotation encryption is symmetric; to encrypt a message you move each letter forward by a fixed amount, and to decrypt it you move each letter back by that same amount. If I want to send you message encrypted using symmetric key encryption then we need to agree on a shared key ahead of time. This type of encryption has its uses (such as in the post-key exchange phase of the TLS protocol), but I can’t think of any way to use it to solve our problem.

Public key cryptography is much more interesting, because different keys are used for encryption and decryption. An individual who wants to use public key cryptography starts by using another algorithm (the details of which aren’t important here) to generate two keys, known as a keypair. The most important property of this keypair is that a message encrypted by one key in the pair can only be decrypted by the other key. This means that neither key in the pair is able to decrypt a message that it itself encrypted. This might be tricky to wrap your head around, but the maths work out, I promise.

One key in the pair is designated as the public key, and the other as the private key. The public key is not at all sensitive. It can be published and distributed freely to anyone, even someone who the keys’ creator doesn’t trust. The private key is, of course, private, and so is kept secret. Now anyone who wants to send the keys’ creator a secret message should encrypt it using the creator’s published public key. Neither the sender nor the recipient needs to worry about the encrypted message being intercepted. An attacker could get their hands on both the encrypted message and the public key used to encrypt it. However, they would be unable to decrypt the message without the corresponding private key. So long as the private key remains truly private, messages encrypted with the public key remain truly secure.

Yes yes we all knew that, grumps Steve. How does any of it help us?

It helps us, says Kate, because it means that we can encrypt the solution to a level in a way that we can decrypt but our players can’t. This means that it’s safe for us to include the solution in our level files. To set this up, we generate a public/private keypair and package the public key with our game. When a level creator creates a level, they demonstrate a solution to it. The level editor records this solution; encrypts it using our public key; and includes the encrypted solution in the level file that it exports. The creator emails the file to their friends to play. The level file still includes a solution, but now it’s encrypted so players can’t access it. This is good.

However, if players can’t access the solution, this means that our game can’t either. This in turn means that the game can’t play through the level to check whether the solution is valid. To get round this, the game sends both the level and the solution over the internet to a server run by Stevesoft…

…then the server decrypts the solution, sends it back to the game, and the game validates it! I’d been thinking of something like that! you say, feigning support and making a grab for some of the credit.

Kate sighs. No, doofus, she says. If we did that then the player could just send us the encrypted solution themselves, pretending to be a copy of the game. We’d send them back the decrypted solution, then they could use it to cheat their way through the level again. Instead, we need to have our server decrypt the solution (using our private key), then, still on the server, run the solution through the level to check if it’s valid. Finally, the server sends a response back to the game saying whether the encrypted solution was valid or not, but containing no information about what the solution actually was.

You try to claim that this is all what you meant, but no one believes you. You go back on the offensive, pointing out that it would be inefficient to force the Stevesoft server to play through the level every time someone wanted to play it. Instead, the game client should save the results of each verification it requests from Stevesoft so that it only has to verify each level once. Plus, the Stevesoft servers should save the results of their solution play-throughs and store them in a cache. Then if the servers are asked to verify a level and a solution that they’ve already seen, they can read the result out of the cache without having to play through it again.

Aren’t we just back at my centralized database solution? asks Otekah. There are some superficial similarities, you reply, but this approach has several key advantages. First, we don’t have to store the entire contents of each level in our database, because we’re only responsible for verifying levels, not distributing them. Storage is cheap, but Stevesoft is broke. Second, and most important, our server isn’t a critical, central repository of any persistent data. In your centralized database approach, if our server got wiped and we had to rebuild it from scratch, we’d lose all of our players’ levels and hard work. Obviously we should keep backups of our database and run multiple redundant copies and all of that dorky stuff, but I think we all know that none of us can be bothered. However, in the public key cryptography approach, our servers don’t need to be anything like as stable and reliable. In this world, if our servers get wiped then all we lose is our cache of levels that we’ve previously verified. This would be irritating, but all it would mean is that we have to re-run our verification the next time someone asked us to verify a level, instead of reading a previous calculated result straight out of our cache. None of the data that we store is critical.

7. Can we use public-key cryptography? Take 2

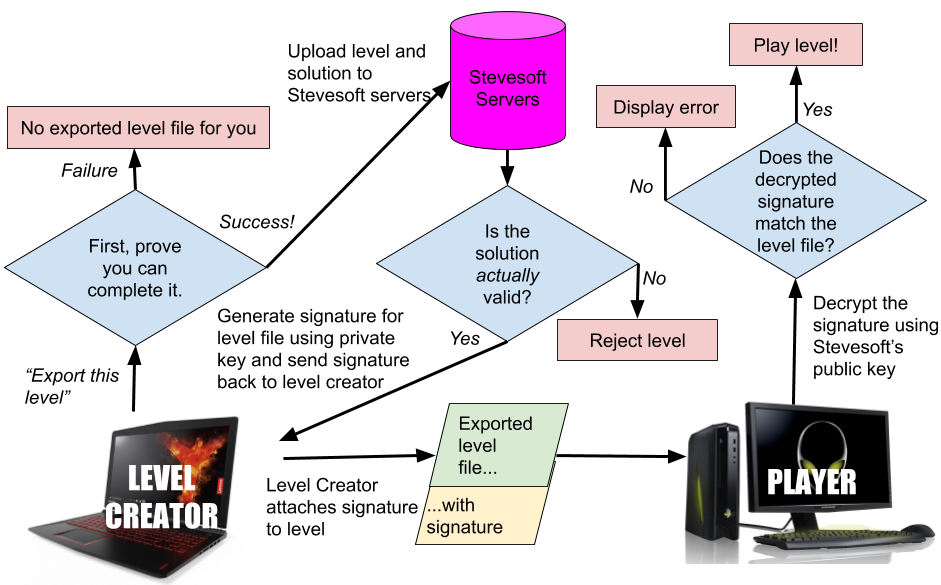

Otekah hems and haws then hurries to the whiteboard, which is actually just the library wall plus a pot of sharpies. What if, she says, we inverted this approach? Instead of validating a level’s solution when a player wants to play it, we instead validate it when a creator creates it.

When a creator wants to export a level, they demonstrate a solution, as per usual. But this time the level editor immediately sends the level and its solution to the Stevesoft servers. The server plays through the solution. If it is valid, it sends the level creator back a cryptographic “seal of approval”, certifying that the level is solvable. The level editor exports the level, but instead of attaching the solution or an encrypted version of the solution, it attaches the seal of approval.

Finally, when a player loads a level, the game checks to see whether the level file contains a valid seal. If it does, the game knows that Stevesoft has played through the level and certified it to be solvable. If it does not, it rejects it. Everyone is safe; job done.

That sounds nice, says Steve. But how are you generating these magic seals of approval? Surely the noxious douchebags who play our game will figure out how to forge them too?

I was getting to that, says Otekah. The “seals of approval” aren’t made using magic; they’re made using cryptography. As you’ll recall, a keypair’s public and private keys are each able to decrypt messages encrypted by the other. When you want to send secret information to a recipient, as in the approach Kate was just describing, you encrypt it using their public key and they decrypt it using their private key.

But public-key cryptography isn’t only useful for keeping information secret. It’s also useful for making information public, while ensuring that readers know that the information has been officially endorsed and approved by you. To do this you use the same encryption keys we just discussed to create a cryptographic signature.

First, you take the message that you want to approve and encrypt it using your private key. This encrypted text is the message’s cryptographic signature. Next, to prove to a recipient that you have approved the message, you send them both the message and its signature. Finally, the recipient can use your public key to decrypt the signature, and verify that the decrypted text matches the original message. This proves that the signature must have been originally created using your private key, which only you have access to. This means that the recipient can be confident that you were the creator of the signature, and that you approve the message.

We can use this technique to generate cryptographic seals of approval for level files, once their creator proves to us that they can be solved. When a level creator wants to export a level, their level editor sends their level and solution to our server. Our server verifies that the given solution does indeed complete the level, and if it does, it uses our private key to sign the contents of the level and sends the signature back to the level creator. The creator’s level editor attaches the signature to the level file. When a player loads the level, their game uses the Stevesoft public key (bundled with the game) to decrypt the signature. If it matches the contents of the level file, the game knows that Stevesoft has verified that the level is solvable. Signatures can’t be forged, because they can only be generated using our private key, which only we have access to. Signatures can’t even be transferred from a valid level to an invalid one, because the decrypted signature has to match exactly the contents of the level.

I hear you snark - why is this any better than using our public key to encrypt the solution? Three reasons. First, it means that our server only ever has to verify a level once: when it’s created. Players don’t need our server in order to check whether a level’s signature is valid - all they need is our public key in order to validate the signature that we already generated. This means less load on our servers, and means we don’t even need to bother keeping a cache of verification results.

Second, it mitigates the consequences of our private key getting stolen. In the previous approach, anyone who hacked our systems and stole a copy of our private key would be able to use the key to decrypt the solution to any previously-published level. This would be a catastrophe. However, the second, signing approach doesn’t suffer from this problem. We don’t need to attach an encrypted copy of the solution to every level - all we need to attach is a harmless cryptographic signature.

That’s all true, says Kate, but I still think that my encryption approach is better. If our private key gets stolen then it’s undeniably annoying that players can cheat and get the solution to all levels, but at least we’ll still have the ability to tell non-cheating players whether a level has a solution or not. In your signing solution, if our private key gets stolen then the thief could use it to generate signatures for impossible levels. We would have to generate a new keypair; distribute its public key to all game clients; and start using that to sign all new levels instead. However, we would now have no idea whether any level signed with our old, compromised key was truly valid. Players have no way to tell the difference between valid levels that were legitimately signed by Stevesoft before the compromise, and invalid levels that were sneakily signed by an attacker after it. They’ll just have to play and hope that the level is valid.

Plus, it’s not necessarily true that your signing solution will cause less load on our servers than my encryption one. In my version, we have to make one validation request whenever a player wants to play a level for the first time. If 100 players want to play a level, we’ll make 100 validation requests, but if no one plays a level, we never need to validate it. In your solution, we always make 1 validation request for every level as soon as it’s created. If lots of levels get created but never played, your solution will cause more load on our servers.

A final difference between our solutions is that my encryption solution allows level creators to create and export levels even when their internet isn’t working. This is because all they need in order to create a level file is our public key in order to encrypt their solution. However, my solution does require players to have an internet connection in order to play a level so that they can send it to our servers and we can validate the encrypted solution. Your solution is the opposite - creators need an internet connection when they want to export a level so that we can validate their solution and give them a signature, but players don’t need an internet connection in order to use our public key to validate this signature.

It’s dark outside. If the library were open it would have closed hours ago. The security guard comes up the stairs; you open Twitter and shake your phone at him, menacingly. He backs away.

So where does this all leave us? Kate asks. Silence.

This is all very clever, Otekah starts. But isn’t it a bit…much? We could keep going like this forever. We could allow third-parties to verify levels. We could develop an entire public key infrastructure to make our cryptography even more robust and flexible. These would all be fun projects to blackmail some interns into doing. But shouldn’t we just do the thing with the centralized database? If enough people upload enough levels to make the server bills expensive then surely we’ll have sold enough copies of the game to cover them?

Steve Steveington, sort-of-CFO, sighs. I suppose you’re right, he says. Can you put something together this week?

Well I don’t know…starts Otekah. Steve flaps a dossier of misfiled tax returns. Absolutely! she finishes.

Everyone packs up their stuff and leaves. You hang back. Don’t wait for me, you shout. No one waits for you. When you’re absolutely sure everyone has gone, you touch the drawings on the wall. You were a cryptographer, if only for a day.