How does online tracking actually work?

20 Nov 2017

The online tracking industry is both horrifying and begrudgingly impressive. No human being wants to give trackers any of their data. No one wants trackers to know which websites they’ve been looking at, what their email address is or which other devices also belong to them. Browser developers are shutting down some of the more underhanded monitoring techniques, and some state regulators are starting to draw some hard frontiers for the wild-west of online tracking.

But online advertisers still seem to know an awful lot about what you’ve been looking at.

Trackers don’t need any special technology to siphon off this data. They simply exploit the edge-cases of how the internet delivers information, in often fascinating ways. Learning how trackers work teaches you a lot about the guts of the internet, which parts of your data are actually at stake, and how to mount an athletic defense. Finely-targeted online advertising still pays for many of the best and worst websites on the internet, and it’s not going anywhere.

In order to understand online tracking, we first need to properly understand its primary, oft-misunderstood tool: cookies.

What is a cookie?

A cookie is a small text file created by your browser and stored on your device. When you visit a website, your browser sends it a message known as an HTTP request. The website responds to your browser’s message with both the content you asked for and any cookies it would like your browser to save. Your browser saves the cookies and notes the domain of the website that they belong to. It then appends a website’s cookie data to every future request that it makes to that website’s domain (subject to a set of security rules that prevent the contents from leaking to other parties). Modern websites use cookies for two main purposes - keeping you logged in and tracking your behavior.

How websites use cookies to log you in

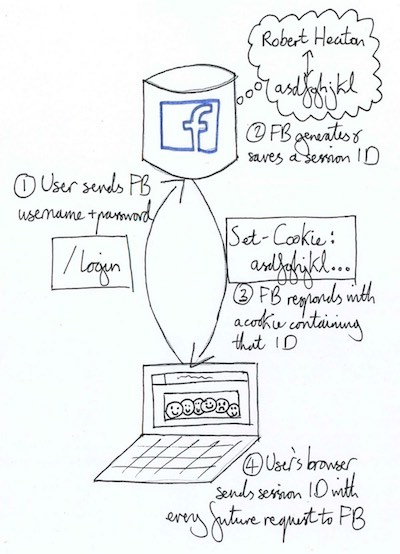

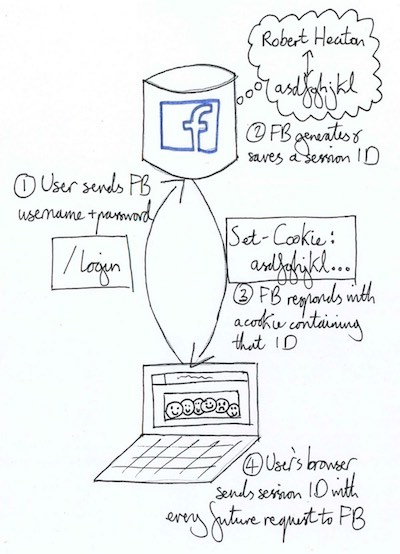

When you log in to a website, like Facebook, your browser sends it a message (again in the form of an HTTP request) with your username and password. If this login request is successful, the response will typically instruct your browser to set a cookie containing a long, random session ID. Facebook saves the fact that it assigned you this session ID to its database, and so when your browser appends it to future requests to Facebook, it immediately knows and trusts who you are without having to explicitly ask you for your password again.

Without a mechanism like the cookie, you would have to enter your username and password for every single request that you sent to Facebook. It would be like having to get a new security card every time you wanted to go into your office. With cookies, you only have to register for the security card once, and then whenever you swipe it, the door, elevator or courtesy robot knows who you are and where you’re allowed to go. If you delete your Facebook cookies then its as though you incinerated your ID card. Facebook doesn’t know who you are anymore, and so you have to login again to re-prove your identity and get a new session ID.

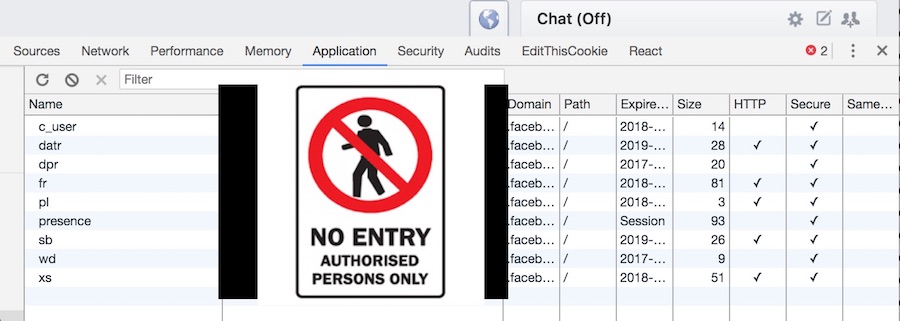

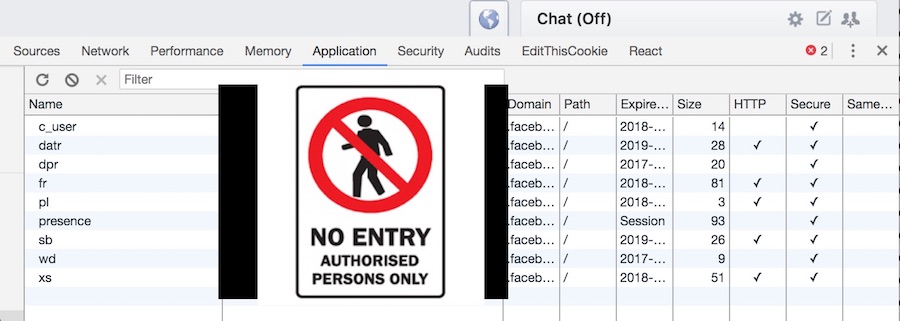

Here’s a picture of the cookies set on my laptop by Facebook.com. I’ve taken great, extreme, paranoid care to blur out their actual contents. Your login cookies aren’t just a handy reminder of the fact that you are logged in; they are fundamentally what it means to be logged in. If you copied my cookies and saved them on your computer (which is not hard - remember, they are just text files), then as far as Facebook is concerned, you are me. This is why your browser has to make sure not to expose your cookies to the wrong people - knowing my cookies is like cloning my ID card. Stealing the contents of a victim’s cookies is known as a cookie tossing attack.

How websites use cookies to track you

It is possible for websites to monitor their traffic without using cookies. For example, a website doesn’t need cookies to find out how many page views they have had. All they have to do is look at their server logs and see how many requests their server received. They could even look at the details of the requests (such as their IP addresses and User-Agent headers) to get an idea of where in the world their users are and whether they’re browsing on their laptop, phone, coffee machine or Nintendo Wii. But cookies make tracking even more powerful and personal.

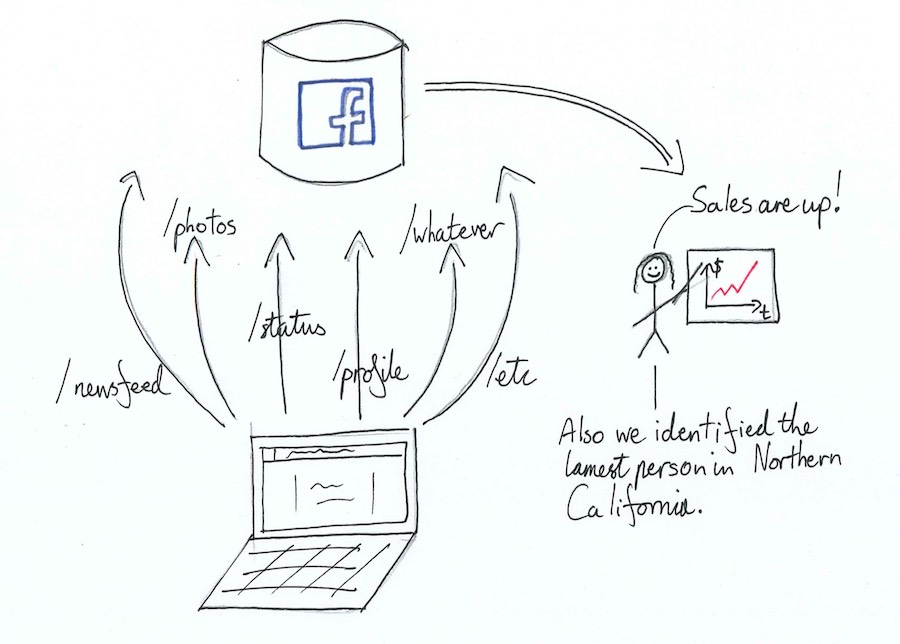

Websites don’t just care about raw view counts - they also care about the users behind those counts. If they can group together activity by the same user then they can better understand how individual users are interacting with their site. How many pages are they viewing each visit? How often do they come back? This might be in order to improve their product, massage their egos or serve targeted ads.

If a website requires its users to log in then they can easily be identified by their existing login cookies. The website can therefore already see everything that their users do without having to perform any extra work. The session IDs from users’ login cookies are attached to each request that the website receives. They can use these IDs to map requests to users, count up all the pages that Alice, Bob and Eve requested last Tuesday and start drawing graphs. They are unlikely to want to bother looking at exactly which pages Alice looked at at exactly what time, and probably have some amount of access-control to keep the user-by-user data private. But there is no technical guarantee of this - they are perfectly able to collect and inspect a logged-in user’s browsing history in a completely deanonymized form if they decide they want to. This information is generated as a direct by-product of your requests to load a website, and the only way you can prevent it from being collected is to not visit the website in the first place.

Even websites that do not require users to log in to any systems (such as news sites, shops or blogs) can still collect this kind of behavioral data. They can still set a cookie on your device when you first load the website, containing a randomly generated ID (eg. arewoiufjlknbvjksdf). Your browser will append this cookie and the ID inside it to every request it sends to their domain, just as it did for the logged-in session ID cookie. The website can therefore use this ID to link together your activity in a similar way to that of a logged-in user. They won’t know your name or email address or any of your personal identifiable information (unless they put in a bit more work), but they will know that everything you do on the site was done by the same person. They can use this information for almost any purpose they like, from improving their site to massaging prices.

How third-party tracking tools use cookies

In practice, websites usually track non-logged in users in using external, third-party software like Google Analytics or AdRoll. These specialized trackers are typically much more powerful and easier to manage than handling tracking in-house, and come in two main flavors: single- and multi-website trackers. Single-website trackers (like Google Analytics) keep the data of each of their client websites siloed and isolated from each other. This makes them less powerful but better for consumer privacy, as the tracker is unable to join up a user’s activity on different websites.

By contrast, multi-website trackers (like AdRoll) roll up and share users’ activity across all of their clients (and beyond). They are therefore much more powerful, with many rather discomforting integrations with other data stores that can help websites learn more about otherwise anonymous users. They are also, in this author’s humble and understated opinion, a consumer privacy disaster zone.

Many people object to being tracked by third-party software of any kind in any way. They believe that the only relationship they have consented to is with the specific website in their URL bar, and it is unacceptable for their behavioral data to be sent to a third party’s servers without their explicit consent. Personally, as long as my behavioral data is only being stored by these third-parties, and is not shared with other companies, I am relatively happy. I still block all third-party trackers that I am able to, mostly because I can, but I don’t have much of a fundamental problem with them so long as they keep my data to themselves. I use Google Analytics, a third-party tracker, on this site, and I still sleep fairly well at night as long as I don’t drink any coffee after three pm.

However, there are many third-party trackers that are dedicated to tracking and connecting your behavior across multiple, unrelated websites. I find these multi-website trackers much more disturbing. By combining their data, trackers and their clients are able to assemble a much more complete picture of your online activities. This allows them to show you ever more precisely targeted ads, tailor prices to the perceived depth of your pockets, or even to alter website content based on what they think you want to hear. They would then be neglecting their fiduciary duty to their shareholders if they didn’t sell your data on to as many other companies as possible as well.

I believe that these cross-website trackers are extremely troubling for online privacy. Whilst the word “anonymous” and a multitude of synonyms are littered throughout the tracking industry literature, linking your pseudonomous tracking profile and all its foibles back to your real-world identity is extremely possible for a tracker with enough data. You just have to hope that they don’t. Multi-website trackers are the main reason that I recommend you install an adblocker if you haven’t done so already.

With all of this in mind, let’s look at how single- and multi-website trackers work.

Single-website trackers

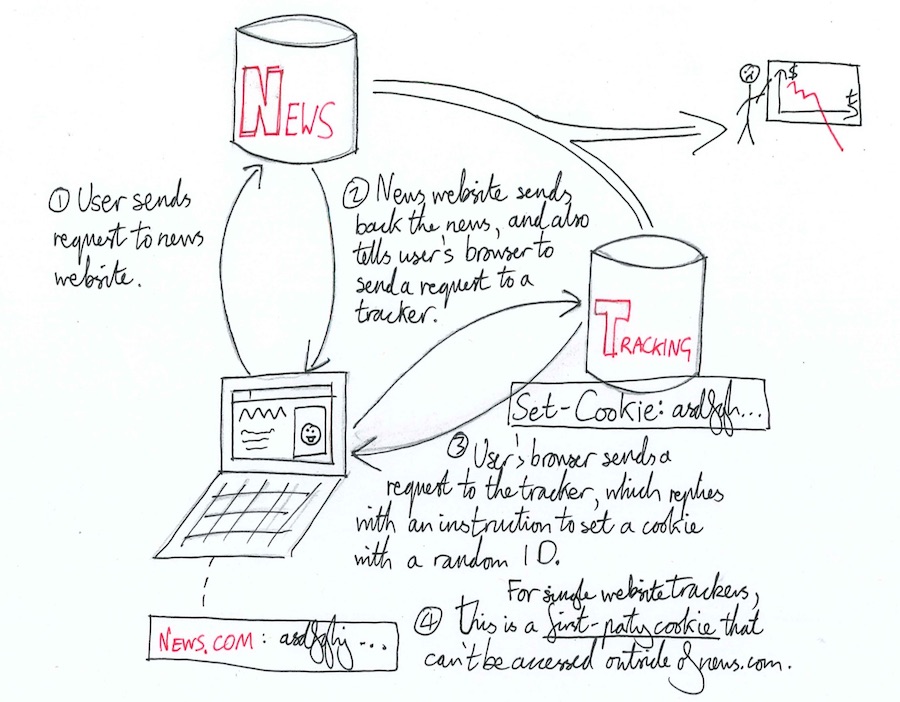

A third-party tracker is run by a completely different company on a completely different server to the website whose users they are tracking. In order to track the website’s users, they need to be separately notified whenever a user loads a page on the website. There are many ways in which this notification could be sent, but the way that the tracking industry has settled on is known as a tracking pixel or beacon.

The idea of a tracking pixel is to make your browser send an HTTP request to the tracker’s servers every time your browser loads a page on the website. By collecting data on these secondary requests, the tracker implicitly collects data on users of the website itself. The most common and reliable way of doing this is for the website to include in its code a tiny snippet of the Javascript written by the tracking company. When you load the website, this code runs inside your browser and asks your browser to load a tiny image, located on the tracking company’s servers. Your browser obediently sends an HTTP request to their servers, and when it receives the response containing a transparent 1x1 pixel image (a tracking pixel).

It also receives instructions to create a cookie containing one of those familiar long, unique, randomly generated session IDs. This ID is sent to the tracker every time your browser requests the tracking pixel in the future. The details of this cookie and how its information is sent to the tracker are what distinguish single- and multi-website trackers. In both cases, the third-party tracker is able to use the ID to group together all requests and pageviews that come from the same user, in much the same way as websites whose users are directly logged in.

A single-website tracker stores the unique ID in a first-party cookie. This means that it is labelled as having been created by the website you believe you are viewing - the one in your URL bar. Cookie security rules mentioned earlier mean that the cookie will not be sent with requests to the domains of any other websites, and that only Javascript code running on a website on that domain is allowed to access it. The ID is isolated to this one website, and will not follow you around the web.

Whilst a prominent single-website tracker like Google Analytics may well know about your activity on many websites individually, you are assigned a different, unconnected ID for each new website. We should not be complacent - it would not be surprising if Google had other ways of connecting up your activity across the internet - but they are not able to do so by simply matching up Google Analytics IDs across websites.

Since the cookie is not assigned to the tracker’s domain, the tracker won’t automatically be sent your session ID cookie with every HTTP request to it. To get around this, the tiny snippet of Javascript code that is responsible for making tracking requests reads the cookie and appends the ID inside it to the URL of the tracking pixel that it requests. This is allowed because the Javascript is running in the context of the main website. The tracker reads the ID from the URL parameters and uses it to identify the user as normal.

There is no reason why the tracking beacon has to be a 1x1 pixel image. It could be a generic HTTP request made direct from Javascript, or a request for any other type of media. However, many browsers are wary of strange looking requests like these and are more likely to block them, whereas very few prevent requests to load a humble image. This kind of cross-domain media loading is how the internet was designed to be used for images and videos, and it’s been smart business by tracking companies to piggy-back on it rather than try and reinvent their own, suspicious-looking wheel.

Cross-website trackers

As we have seen, single-website trackers store their unique tracking IDs in first-party cookies that belong to the website, not the tracker. This isolates the ID so that it can only be used in the context of that single, specific website. By contrast, cross-website trackers store their IDs in third-party cookies that belong to the tracker. This seemingly innocuous difference completely changes the way the tracking system works. Now the tracker is in charge.

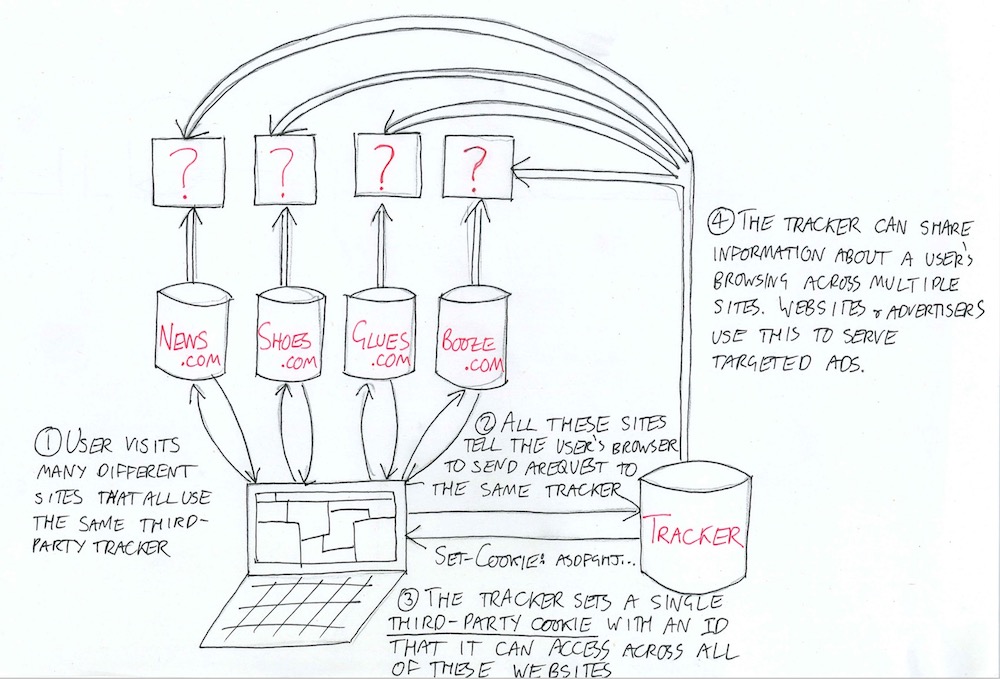

There is nothing intrinsically special or harmful about a third-party cookie. It is simply a cookie that belongs to a domain other than the one in your URL bar. However, since the cookie set by the tracker is now marked as belonging to the tracker’s domain, your browser will automatically append it to every request that it sends to that domain. Crucially, it will do this not only when tracking you on the website you are currently visiting, but also on any other website on the entire internet that uses its tracking software. And because it is accessing the same cookie for each website, it will see the same ID when it tracks your behavior on any of its clients, be that news.com, shoes.com, glues.com or booze.com. This single tracker is therefore able to identify you and build up an extensive picture of your online activity across many domains; their reach is limited only by the number of clients they have. As with so many other things on the internet, this data is mostly sold to other companies and used to target you with even more precise ads.

In advertising, one particularly common use of your data is called retargeting. A merchant, OverpricedDomesticFlights.net, runs tracking software on their website that tags visitors with a tracking cookie as above. An online publisher, NewsFromQuestionableSources.com, runs the same software on their site. Since the tracking cookie set on the merchant’s site belongs to the tracker, they are able to access it from any other website that is running their tracking software. Since the tracker sees the same tracking ID for both ODF.net and NFQS.com, they are able to detect when the same user has visited both sites. The tracker can therefore see when a visitor to News Of Questionable Veracity has also previously visited Overpriced Domestic Flights. It can then show them an ad for some expensive trips to Phoenix to try and tempt them back.

That any company is able to build up a rich picture of their online behavior should be troubling to consumers. That it is a company about which they know nothing, and to which they have never given any form of consent, is even worse.

Conclusion

Most browsers now have a built-in option to simply block third-party cookies. This prevents the particular strain of cookie-based cross-website tracking described above. However, as cookies become an increasingly fragile and unreliable tracking mechanism, many trackers are switching to cookieless ways of implementing the same basic structure. These methods include exploiting your browser’s cache, fingerprinting your device and exploiting your browser’s cache again.

If you want to increase your privacy online, you should start by installing an adblocker. Adblockers are important, not because they block ads, but because they block the snooping that goes into selling and serving them. Most adblockers (such as uBlockOrigin) block requests from your browser to domains known to belong to trackers, and further restrict the types of cookies that domains can set. There’s nothing finer than a completely unpersonalized ad, or at least one only personalized to a website’s broad audience segment.

Even ad blockers don’t keep you private on the internet by any stretch of the imagination. Third-party trackers have plenty of options for circumventing their protections, and whether they use them or not is primarily dependent on state regulation and their PR team’s appetite for risk. First-parties still see everything that you do, and the only way to avoid sending a first-party any information is to close your laptop. Using a VPN or even Tor goes a long way to prevent unintentional leakage of your location or identity information, but as long as you use Facebook, Facebook is going to know a lot about you.

I’m going to be writing a lot more on the subject of online tracking; if you’d like to know more about what advertisers know about you then you should sign up below and get these essays sent to you via email.

The online tracking industry is both horrifying and begrudgingly impressive. No human being wants to give trackers any of their data. No one wants trackers to know which websites they’ve been looking at, what their email address is or which other devices also belong to them. Browser developers are shutting down some of the more underhanded monitoring techniques, and some state regulators are starting to draw some hard frontiers for the wild-west of online tracking.

But online advertisers still seem to know an awful lot about what you’ve been looking at.

Trackers don’t need any special technology to siphon off this data. They simply exploit the edge-cases of how the internet delivers information, in often fascinating ways. Learning how trackers work teaches you a lot about the guts of the internet, which parts of your data are actually at stake, and how to mount an athletic defense. Finely-targeted online advertising still pays for many of the best and worst websites on the internet, and it’s not going anywhere.

In order to understand online tracking, we first need to properly understand its primary, oft-misunderstood tool: cookies.

What is a cookie?

A cookie is a small text file created by your browser and stored on your device. When you visit a website, your browser sends it a message known as an HTTP request. The website responds to your browser’s message with both the content you asked for and any cookies it would like your browser to save. Your browser saves the cookies and notes the domain of the website that they belong to. It then appends a website’s cookie data to every future request that it makes to that website’s domain (subject to a set of security rules that prevent the contents from leaking to other parties). Modern websites use cookies for two main purposes - keeping you logged in and tracking your behavior.

How websites use cookies to log you in

When you log in to a website, like Facebook, your browser sends it a message (again in the form of an HTTP request) with your username and password. If this login request is successful, the response will typically instruct your browser to set a cookie containing a long, random session ID. Facebook saves the fact that it assigned you this session ID to its database, and so when your browser appends it to future requests to Facebook, it immediately knows and trusts who you are without having to explicitly ask you for your password again.

Without a mechanism like the cookie, you would have to enter your username and password for every single request that you sent to Facebook. It would be like having to get a new security card every time you wanted to go into your office. With cookies, you only have to register for the security card once, and then whenever you swipe it, the door, elevator or courtesy robot knows who you are and where you’re allowed to go. If you delete your Facebook cookies then its as though you incinerated your ID card. Facebook doesn’t know who you are anymore, and so you have to login again to re-prove your identity and get a new session ID.

Here’s a picture of the cookies set on my laptop by Facebook.com. I’ve taken great, extreme, paranoid care to blur out their actual contents. Your login cookies aren’t just a handy reminder of the fact that you are logged in; they are fundamentally what it means to be logged in. If you copied my cookies and saved them on your computer (which is not hard - remember, they are just text files), then as far as Facebook is concerned, you are me. This is why your browser has to make sure not to expose your cookies to the wrong people - knowing my cookies is like cloning my ID card. Stealing the contents of a victim’s cookies is known as a cookie tossing attack.

How websites use cookies to track you

It is possible for websites to monitor their traffic without using cookies. For example, a website doesn’t need cookies to find out how many page views they have had. All they have to do is look at their server logs and see how many requests their server received. They could even look at the details of the requests (such as their IP addresses and User-Agent headers) to get an idea of where in the world their users are and whether they’re browsing on their laptop, phone, coffee machine or Nintendo Wii. But cookies make tracking even more powerful and personal.

Websites don’t just care about raw view counts - they also care about the users behind those counts. If they can group together activity by the same user then they can better understand how individual users are interacting with their site. How many pages are they viewing each visit? How often do they come back? This might be in order to improve their product, massage their egos or serve targeted ads.

If a website requires its users to log in then they can easily be identified by their existing login cookies. The website can therefore already see everything that their users do without having to perform any extra work. The session IDs from users’ login cookies are attached to each request that the website receives. They can use these IDs to map requests to users, count up all the pages that Alice, Bob and Eve requested last Tuesday and start drawing graphs. They are unlikely to want to bother looking at exactly which pages Alice looked at at exactly what time, and probably have some amount of access-control to keep the user-by-user data private. But there is no technical guarantee of this - they are perfectly able to collect and inspect a logged-in user’s browsing history in a completely deanonymized form if they decide they want to. This information is generated as a direct by-product of your requests to load a website, and the only way you can prevent it from being collected is to not visit the website in the first place.

![]()

Even websites that do not require users to log in to any systems (such as news sites, shops or blogs) can still collect this kind of behavioral data. They can still set a cookie on your device when you first load the website, containing a randomly generated ID (eg. arewoiufjlknbvjksdf). Your browser will append this cookie and the ID inside it to every request it sends to their domain, just as it did for the logged-in session ID cookie. The website can therefore use this ID to link together your activity in a similar way to that of a logged-in user. They won’t know your name or email address or any of your personal identifiable information (unless they put in a bit more work), but they will know that everything you do on the site was done by the same person. They can use this information for almost any purpose they like, from improving their site to massaging prices.

How third-party tracking tools use cookies

In practice, websites usually track non-logged in users in using external, third-party software like Google Analytics or AdRoll. These specialized trackers are typically much more powerful and easier to manage than handling tracking in-house, and come in two main flavors: single- and multi-website trackers. Single-website trackers (like Google Analytics) keep the data of each of their client websites siloed and isolated from each other. This makes them less powerful but better for consumer privacy, as the tracker is unable to join up a user’s activity on different websites.

By contrast, multi-website trackers (like AdRoll) roll up and share users’ activity across all of their clients (and beyond). They are therefore much more powerful, with many rather discomforting integrations with other data stores that can help websites learn more about otherwise anonymous users. They are also, in this author’s humble and understated opinion, a consumer privacy disaster zone.

Many people object to being tracked by third-party software of any kind in any way. They believe that the only relationship they have consented to is with the specific website in their URL bar, and it is unacceptable for their behavioral data to be sent to a third party’s servers without their explicit consent. Personally, as long as my behavioral data is only being stored by these third-parties, and is not shared with other companies, I am relatively happy. I still block all third-party trackers that I am able to, mostly because I can, but I don’t have much of a fundamental problem with them so long as they keep my data to themselves. I use Google Analytics, a third-party tracker, on this site, and I still sleep fairly well at night as long as I don’t drink any coffee after three pm.

However, there are many third-party trackers that are dedicated to tracking and connecting your behavior across multiple, unrelated websites. I find these multi-website trackers much more disturbing. By combining their data, trackers and their clients are able to assemble a much more complete picture of your online activities. This allows them to show you ever more precisely targeted ads, tailor prices to the perceived depth of your pockets, or even to alter website content based on what they think you want to hear. They would then be neglecting their fiduciary duty to their shareholders if they didn’t sell your data on to as many other companies as possible as well.

I believe that these cross-website trackers are extremely troubling for online privacy. Whilst the word “anonymous” and a multitude of synonyms are littered throughout the tracking industry literature, linking your pseudonomous tracking profile and all its foibles back to your real-world identity is extremely possible for a tracker with enough data. You just have to hope that they don’t. Multi-website trackers are the main reason that I recommend you install an adblocker if you haven’t done so already.

With all of this in mind, let’s look at how single- and multi-website trackers work.

Single-website trackers

A third-party tracker is run by a completely different company on a completely different server to the website whose users they are tracking. In order to track the website’s users, they need to be separately notified whenever a user loads a page on the website. There are many ways in which this notification could be sent, but the way that the tracking industry has settled on is known as a tracking pixel or beacon.

The idea of a tracking pixel is to make your browser send an HTTP request to the tracker’s servers every time your browser loads a page on the website. By collecting data on these secondary requests, the tracker implicitly collects data on users of the website itself. The most common and reliable way of doing this is for the website to include in its code a tiny snippet of the Javascript written by the tracking company. When you load the website, this code runs inside your browser and asks your browser to load a tiny image, located on the tracking company’s servers. Your browser obediently sends an HTTP request to their servers, and when it receives the response containing a transparent 1x1 pixel image (a tracking pixel).

![]()

It also receives instructions to create a cookie containing one of those familiar long, unique, randomly generated session IDs. This ID is sent to the tracker every time your browser requests the tracking pixel in the future. The details of this cookie and how its information is sent to the tracker are what distinguish single- and multi-website trackers. In both cases, the third-party tracker is able to use the ID to group together all requests and pageviews that come from the same user, in much the same way as websites whose users are directly logged in.

A single-website tracker stores the unique ID in a first-party cookie. This means that it is labelled as having been created by the website you believe you are viewing - the one in your URL bar. Cookie security rules mentioned earlier mean that the cookie will not be sent with requests to the domains of any other websites, and that only Javascript code running on a website on that domain is allowed to access it. The ID is isolated to this one website, and will not follow you around the web.

Whilst a prominent single-website tracker like Google Analytics may well know about your activity on many websites individually, you are assigned a different, unconnected ID for each new website. We should not be complacent - it would not be surprising if Google had other ways of connecting up your activity across the internet - but they are not able to do so by simply matching up Google Analytics IDs across websites.

Since the cookie is not assigned to the tracker’s domain, the tracker won’t automatically be sent your session ID cookie with every HTTP request to it. To get around this, the tiny snippet of Javascript code that is responsible for making tracking requests reads the cookie and appends the ID inside it to the URL of the tracking pixel that it requests. This is allowed because the Javascript is running in the context of the main website. The tracker reads the ID from the URL parameters and uses it to identify the user as normal.

There is no reason why the tracking beacon has to be a 1x1 pixel image. It could be a generic HTTP request made direct from Javascript, or a request for any other type of media. However, many browsers are wary of strange looking requests like these and are more likely to block them, whereas very few prevent requests to load a humble image. This kind of cross-domain media loading is how the internet was designed to be used for images and videos, and it’s been smart business by tracking companies to piggy-back on it rather than try and reinvent their own, suspicious-looking wheel.

Cross-website trackers

As we have seen, single-website trackers store their unique tracking IDs in first-party cookies that belong to the website, not the tracker. This isolates the ID so that it can only be used in the context of that single, specific website. By contrast, cross-website trackers store their IDs in third-party cookies that belong to the tracker. This seemingly innocuous difference completely changes the way the tracking system works. Now the tracker is in charge.

There is nothing intrinsically special or harmful about a third-party cookie. It is simply a cookie that belongs to a domain other than the one in your URL bar. However, since the cookie set by the tracker is now marked as belonging to the tracker’s domain, your browser will automatically append it to every request that it sends to that domain. Crucially, it will do this not only when tracking you on the website you are currently visiting, but also on any other website on the entire internet that uses its tracking software. And because it is accessing the same cookie for each website, it will see the same ID when it tracks your behavior on any of its clients, be that news.com, shoes.com, glues.com or booze.com. This single tracker is therefore able to identify you and build up an extensive picture of your online activity across many domains; their reach is limited only by the number of clients they have. As with so many other things on the internet, this data is mostly sold to other companies and used to target you with even more precise ads.

![]()

In advertising, one particularly common use of your data is called retargeting. A merchant, OverpricedDomesticFlights.net, runs tracking software on their website that tags visitors with a tracking cookie as above. An online publisher, NewsFromQuestionableSources.com, runs the same software on their site. Since the tracking cookie set on the merchant’s site belongs to the tracker, they are able to access it from any other website that is running their tracking software. Since the tracker sees the same tracking ID for both ODF.net and NFQS.com, they are able to detect when the same user has visited both sites. The tracker can therefore see when a visitor to News Of Questionable Veracity has also previously visited Overpriced Domestic Flights. It can then show them an ad for some expensive trips to Phoenix to try and tempt them back.

That any company is able to build up a rich picture of their online behavior should be troubling to consumers. That it is a company about which they know nothing, and to which they have never given any form of consent, is even worse.

Conclusion

Most browsers now have a built-in option to simply block third-party cookies. This prevents the particular strain of cookie-based cross-website tracking described above. However, as cookies become an increasingly fragile and unreliable tracking mechanism, many trackers are switching to cookieless ways of implementing the same basic structure. These methods include exploiting your browser’s cache, fingerprinting your device and exploiting your browser’s cache again.

If you want to increase your privacy online, you should start by installing an adblocker. Adblockers are important, not because they block ads, but because they block the snooping that goes into selling and serving them. Most adblockers (such as uBlockOrigin) block requests from your browser to domains known to belong to trackers, and further restrict the types of cookies that domains can set. There’s nothing finer than a completely unpersonalized ad, or at least one only personalized to a website’s broad audience segment.

Even ad blockers don’t keep you private on the internet by any stretch of the imagination. Third-party trackers have plenty of options for circumventing their protections, and whether they use them or not is primarily dependent on state regulation and their PR team’s appetite for risk. First-parties still see everything that you do, and the only way to avoid sending a first-party any information is to close your laptop. Using a VPN or even Tor goes a long way to prevent unintentional leakage of your location or identity information, but as long as you use Facebook, Facebook is going to know a lot about you.

I’m going to be writing a lot more on the subject of online tracking; if you’d like to know more about what advertisers know about you then you should sign up below and get these essays sent to you via email.