Wacom drawing tablets track the name of every application that you open

05 Feb 2020

Disclaimer: I haven’t asked Wacom for comment about this story because I’m not a journalist and I don’t know how to do that. I don’t believe I’ve got anything important wrong, however.

Chapter 1: The discovery

I have a Wacom drawing tablet. I use it to draw cover illustrations for my blog posts, such as this one:

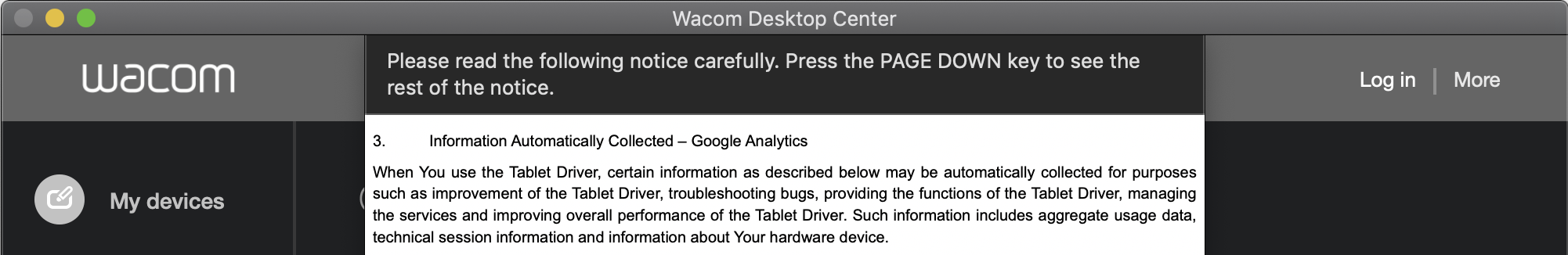

Last week I set up my tablet on my new laptop. As part of installing its drivers I was asked to accept Wacom’s privacy policy.

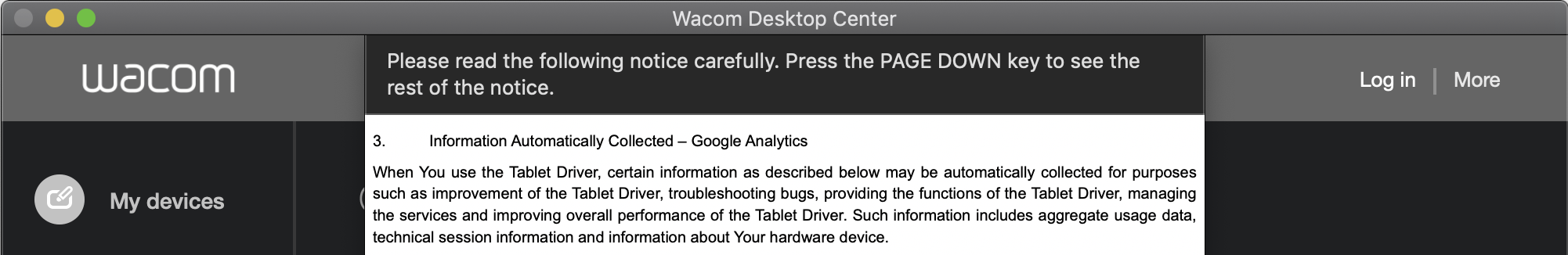

Being a mostly-normal person I never usually read privacy policies. Instead I vigorously hammer the “yes” button in an effort to reach the game, machine, or medical advice on the other side of the agreement as fast as possible. But Wacom’s request made me pause. Why does a device that is essentially a mouse need a privacy policy? I wondered. Sensing skullduggery, I decided to make an exception to my anti-privacy-policy-policy and give this one a read.

In Wacom’s defense (that’s the only time you’re going to see that phrase today), the document was short and clear, although as we’ll see it wasn’t entirely open about its more dubious intentions (here’s the full text). In addition, despite its attempts to look like the kind of compulsory agreement that must be accepted in order to unlock the product behind it, as far as I can tell anyone with the presence of mind to decline it could do so with no adverse consequences.

With that attempt at even-handedness out the way, let’s get kicking.

In section 3.1 of their privacy policy, Wacom wondered if it would be OK if they sent a few bits and bobs of data from my computer to Google Analytics, “[including] aggregate usage data, technical session information and information about [my] hardware device.” The half of my heart that cares about privacy sank. The other half of my heart, the half that enjoys snooping on snoopers and figuring out what they’re up to, leapt. It was a disjointed feeling, probably similar to how it feels to get mugged by your favorite TV magician.

Wacom didn’t say exactly what data they were going to send themselves. I resolved to find out.

Chapter 2: Snooping on the snoopers

I began my investigation with a strong presumption of chicanery. I was unable to imagine the project kickoff meeting in which Wacom decided to bundle Google Analytics with their device, which - remember - is essentially a mouse, but managed to restrain themselves from also grabbing some deliciously intrusive information while they were at it. I Googled “wacom google analytics”. There were a couple of Tweets and Reddit posts made by people who had also read Wacom’s privacy policy and been unhappy about its contents, but no one had yet tried to find out exactly what data Wacom were grabbing. No one had investigated Wacom’s understanding of the phrase “aggregate usage data” or whether it was anywhere near that of a reasonable person.

I told my son to clear my schedule. He bashed two wooden blocks together in understanding, encouragement, and sheer admiration.

In order to see what type of data Wacom was exfiltrating from my computer, I needed to snoop on the traffic that their driver was sending to Google Analytics. The most common way to do this is to set up a proxy server on your computer (I usually use Burp Suite). You tell your target program to send its traffic through your proxy. Your proxy logs the data it receives, and finally re-sends it on to its intended destination. When the destination sends back a response, the same process runs in reverse.

+-------------------------------+

|My computer |

| |

| +------+ +------+ | +---------+

| |Wacom +------->+Burp +-------->+Google |

| |Driver+<-------+Suite +<--------+Analytics|

| +------+ +-+----+ | +---------+

| | Log requests and responses

| v |

| /track?data=... |

| |

+---------------------+---------+

Some applications, like web browsers, co-operate very well with proxies. They allow users to explicitly specify a proxy for them to to send their traffic through. However, other applications (including the Wacom tablet drivers) provide no such conveniences. Instead, they require some special treatment.

Chapter 3: Wireshark

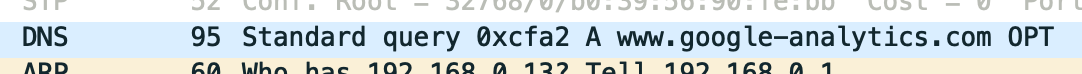

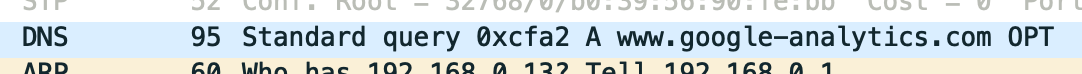

I started with a simple approach that was unlikely to work but was worth a try. I opened Wireshark, a program that watches your computer’s network traffic. I wanted to use Wireshark to view the raw bytes that the Wacom driver was sending to Google Analytics. If Wacom was sending my data over unencrypted HTTP then I’d immediately be able to see all of its gory details, no extra work required. On the other hand, if Wacom was using encrypted TLS/HTTPS then I would be foiled. The traffic would appear as garbled nonsense that I would be unable to decrypt, since I wouldn’t know the keys used to encrypt it. I closed any noisy, network-connecting programs to reduce the chatter on the line, pressed Wireshark’s record button, and held onto my hat.

Unfortunately, no unencrypted HTTP traffic appeared; only encrypted, garbled TLS. But there was good news amidst this setback. Wireshark also picks up DNS requests, which are used to look up the IP address that corresponds to a domain. I saw that my computer was making DNS requests to look up the IP address of www.google-analytics.com. The DNS response was coming back as 172.217.7.14, and lots of TLS-encrypted traffic was then heading out to that IP address. This meant that something was indeed talking to Google Analytics.

I switched tactics and fired up Burp Suite proxy.

Chapter 4: Burp Suite

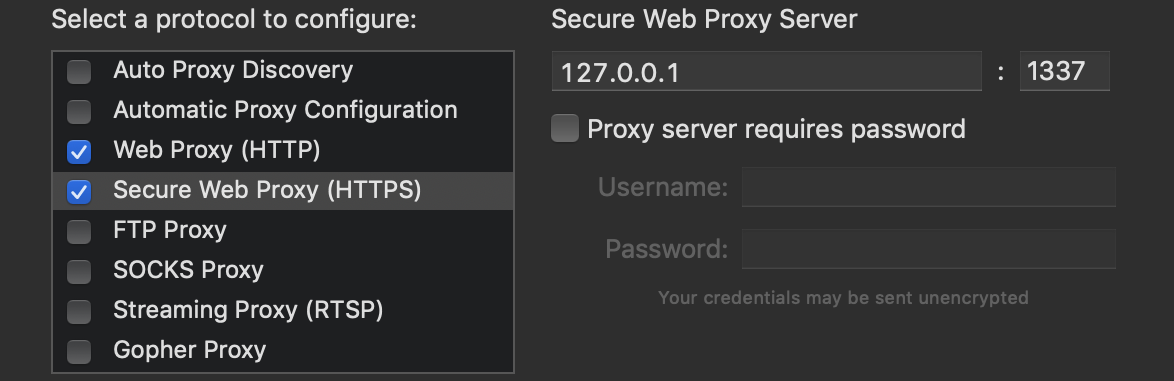

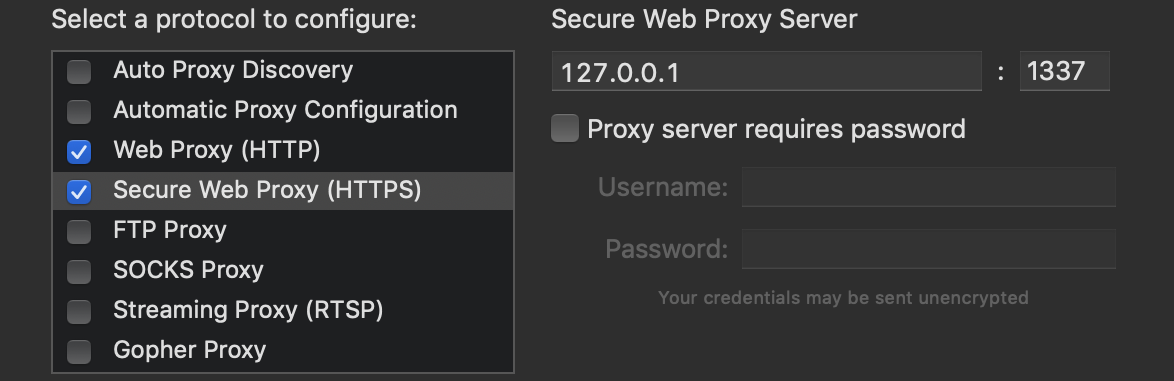

I now had two problems. First, I needed to persuade Wacom to send its Google Analytics traffic through Burp Suite. Second, I needed to make sure that Wacom would then complete a TLS handshake with Burp. To solve the first problem, I configured my laptop’s global HTTP and HTTPS proxies to point to Burp Suite. This meant that every program that respected these global settings would send its traffic through my proxy.

Happily, it turned out that Wacom did respect my global proxy settings - my proxy quickly started logging “client failed TLS handshake” messages.

This brought me to my second problem. Since Wacom was talking to Google Analytics over TLS, it required the server to present a valid TLS certificate for www.google-analytics.com. As far as Wacom is concerned, my proxy was now the server that it is talking to, not Google Analytics itself. This meant that I needed my proxy to present a certificate that Wacom would trust.

(Burp must present a valid cert for www.google-analytics.com)

|

+---------------------|---------+

|My computer | |

| v |

| +------+ +------+ | +---------+

| |Wacom +------->+Burp +-------->+Google |

| |Driver+<-------+Suite +<--------+Analytics|

| +------+ +-+----+ | +---------+

| | Log requests and responses

| v |

| /track?data=... |

| |

+---------------------+---------+

The most difficult part of presenting such a certificate is that it needs to be cryptographically signed by a certificate authority that the program trusts. Burp Suite can generate and sign certificates for any domain, no problem, but since by default no computer or program trusts Burp Suite as a certificate authority, the certificates it signs are rejected (I’ve written much more about TLS and HTTPS here and here).

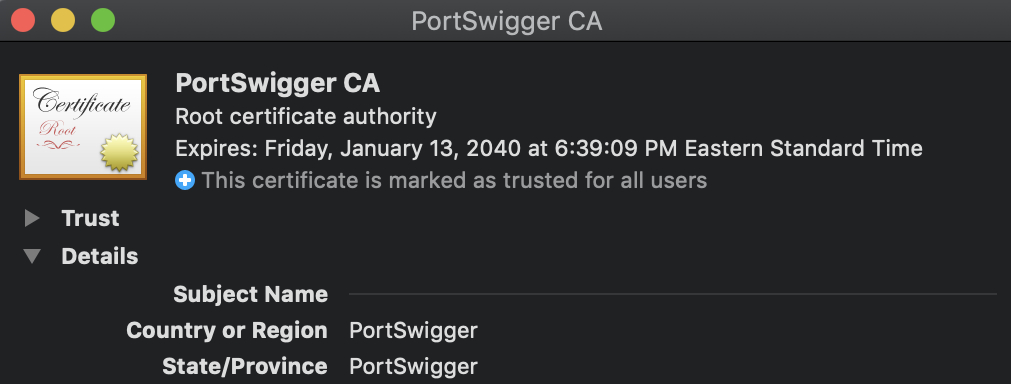

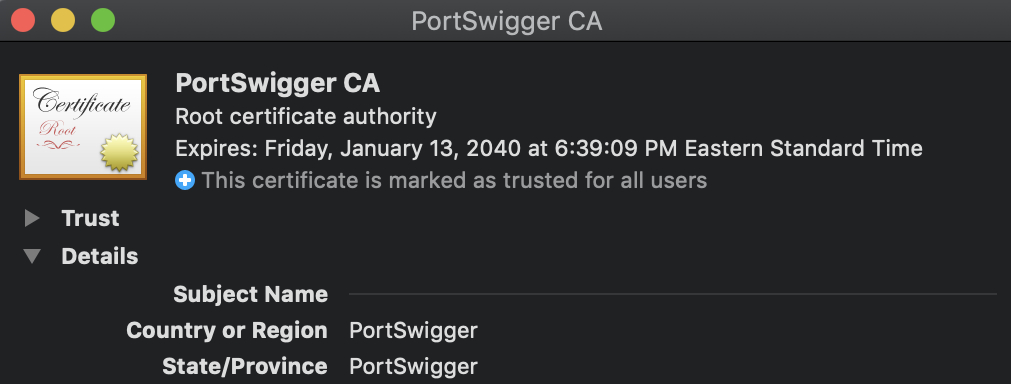

Once again, the process of persuading a web browser to trust Burp’s root certificate is well-documented, but for a thick application like Wacom I’d need to do something slightly different. I therefore used OSX’s Keychain to temporarily add Burp’s certificate to my computer’s list of root certificates.

I assumed that Wacom would load its list of root certificates from my computer, and that by adding Burp to this list, Wacom would start to trust Burp and would complete a TLS handshake with my proxy.

I sat and waited. I watched Wireshark and Burp at the same time. If Wacom failed to connect to Burp, I’d see this failure in Wireshark. I was quite excited.

Nothing happened.

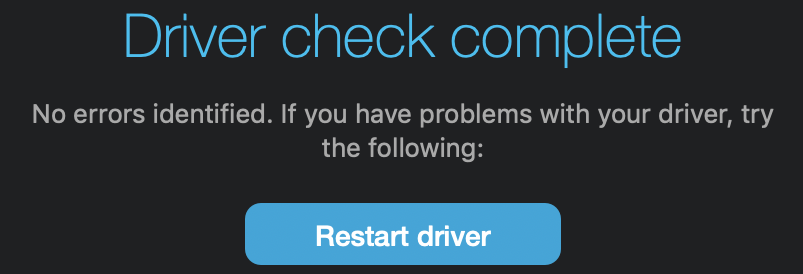

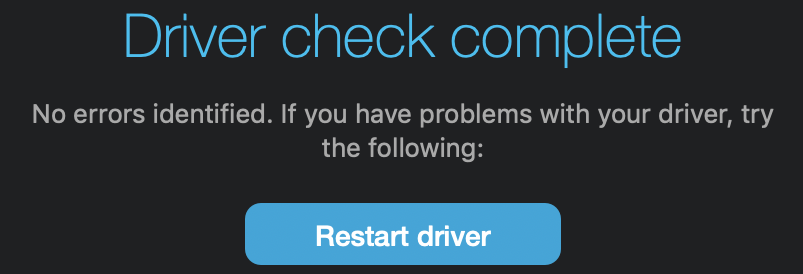

I wondered if the data dumping was triggered by a timer, or by some particular activity, or by both. I tried drawing something using my Wacom tablet. Still nothing. I plugged and unplugged it. Nothing. Then I went into the Wacom Driver Settings and restarted the driver.

Everything happened.

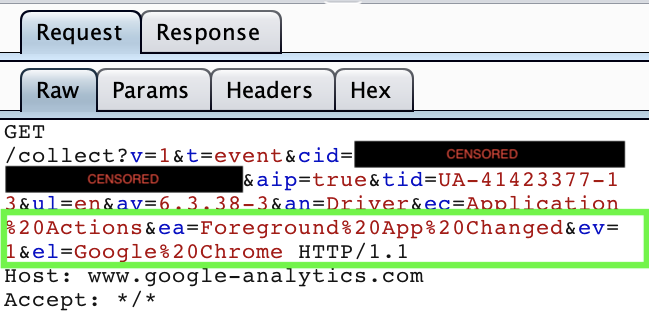

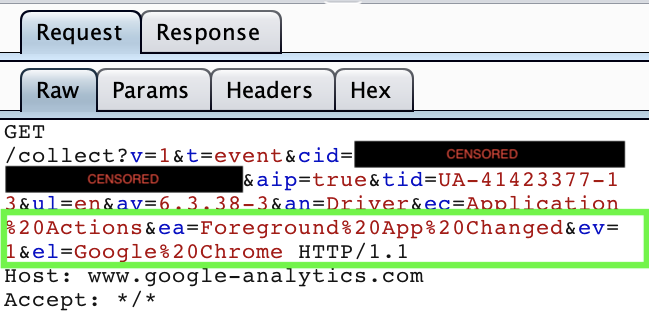

When I restarted the Wacom driver, rather than lose all the data it had accumulated, the driver fired off everything it had collected to Google Analytics. This data materialized in my Burp Suite. I took a look. My heart experienced the same half-down-half-up schism as it had half an hour ago.

Some of the events that Wacom were recording were arguably within their purview, such as “driver started” and “driver shutdown”. I still don’t want them to take this information because there’s nothing in it for me, but their attempt to do so feels broadly justifiable. What requires more explanation is why Wacom think it’s acceptable to record every time I open a new application, including the time, a string that presumably uniquely identifies me, and the application’s name.

Chapter 5: Analysis

I suspect that Wacom doesn’t really think that it’s acceptable to record the name of every application I open on my personal laptop. I suspect that this is why their privacy policy doesn’t really admit that this is what that they do. I imagine that if pressed they would argue that the name of every application I open on my personal laptop falls into one of their broad buckets like “aggregate data” or “technical session information”, although it’s not immediately obvious to me which bucket.

It’s well-known that no one reads privacy policies and that they’re often a fig leaf of consent at best. But since Wacom’s privacy policy makes no mention of their intention to record the name of every application I open on my personal laptop, I’d argue that it doesn’t even give them the technical-fig-leaf-right to do so. In fact, I’d argue that even if someone had read and understood Wacom’s privacy policy, and had knowingly consented to a reasonable interpretation of the words inside it, that person would still not have agreed to allow Wacom to log and track the name of every application that they opened on their personal laptop.

Of course, I’m not a lawyer, and I assume that whoever wrote this privacy policy is.

Wacom’s privacy policy does say that they only want this data for product development purposes, and on this point I do actually believe them. This might be naive, since who knows what goes on behind the scenes when large troves of data are involved. Either way, while I do understand that product developers like to have usage data in order to monitor and improve their offerings, this doesn’t give them the right to take it.

I care about this for two reasons.

The first is a principled fuck you. I don’t care whether anything materially bad will or won’t happen as a consequence of Wacom taking this data from me. I simply resent the fact that they’re doing it.

The second is that we can also come up with scenarios that involve real harms. Maybe the very existence of a program is secret or sensitive information. What if a Wacom employee suddenly starts seeing entries spring up for “Half Life 3 Test Build”? Obviously I don’t care about the secrecy of Valve’s new games, but I assume that Valve does.

We can get more subtle. I personally use Google Analytics to track visitors to my website. I do feel bad about this, but I’ve got to get my self-esteem from somewhere. Google Analytics has a “User Explorer” tool, in which you can zoom in on the activity of a specific user. Suppose that someone at Wacom “fingerprints” a target person that they knew in real life by seeing that this person uses a very particular combination of applications. The Wacom employee then uses this fingerprint to find the person in the “User Explorer” tool. Finally the Wacom employee sees that their target also uses “LivingWith: Cancer Support”.

Remember, this information is coming from a device that is essentially a mouse.

This example is admittedly a little contrived, but it’s also an illustration that, even though this data doesn’t come with a name and social security number attached, it is neither benign nor inert.

Chapter 6: Conclusion

In some ways it feels unfair to single out Wacom. This isn’t the dataset that’s going to complete the embrace of full, totalitarian surveillance capitalism. Nonetheless, it’s still deeply obnoxious. A device that is essentially a mouse has no legitimate reasons to make HTTP requests of any sort. Maybe Wacom could hide in the sweet safety of murky territory if they released some sort of mobile app integration or a weekly personal usage report that required this data, but until then I’m happy to classify them as an obligingly clear case of nefariousness.

Nonetheless, I’m not about to incinerate my Wacom tablet and buy a different one. These things are expensive, and privacy is hard to put a price on. If you too have a Wacom tablet (presumably this tracking is enabled for all of their models), open up the “Wacom Desktop Center” and click around until you find a way to disable the “Wacom Experience Program”. Then the next time you’re buying a tablet, remember that Wacom tries to track every app you open, and consider giving another brand a go.

Epilogue

I finished the first draft of this article three weeks ago. I set up Burp Suite proxy again so that I could grab some final screenshots of the data that Wacom was purloining. I restarted the Wacom driver, as per usual. But nothing happened. Wacom weren’t illegitimately siphoning off my personal usage data any more.

The bastards.

I contemplated pretending I hadn’t seen this and publishing my post anyway. Then I contemplated publishing it with an additional coda explaining this latest development. However, the title “Wacom drawing tablets used to track the name of every application that you open but now seem to have stopped for some reason” didn’t feel very snappy. I decided to do some more investigating.

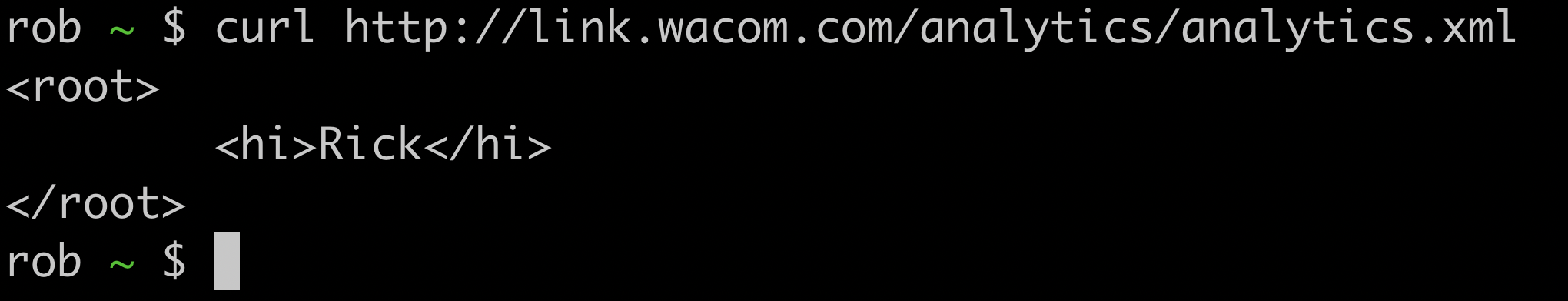

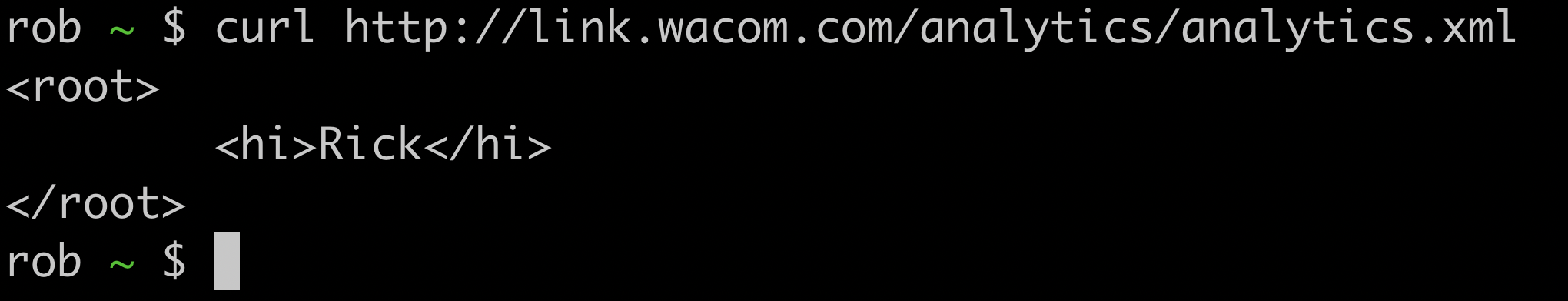

I had previously noticed that, before sending data to Google Analytics, the Wacom driver sent a HEAD request to the URL http://link.wacom.com/analytics/analytics.xml. I hadn’t been able to work out why, and until now I hadn’t thought much of it. However, now Wacom was responding to this request with a 404 “Not Found” status code instead of 200 “OK”. I realized that the request must be some kind of pre-flight check that allowed Wacom to turn off analytics collection remotely without requiring users to install a driver update. Now that the request was failing, Wacom were not sending themselves my data.

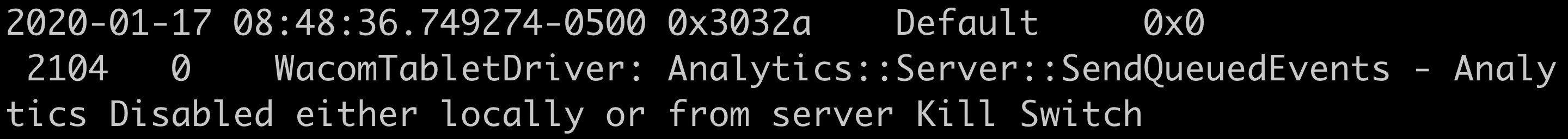

I dug around in the driver’s logfile and found the following snippet that confirmed my suspicions:

I wondered if Wacom had gotten wise to what I was up to and panic-disabled their tracking. This seemed unlikely, although the timing was rather coincidental. I decided that Wacom had probably simply made a boneheaded mistake and accidentally broken their own command-and-control center. I impatiently waited for them to realize their goof and bring their data exfiltration operation back online. I contemplated emailing Wacom to alert them to their problem, but couldn’t come up with a sufficiently innocuous way of doing so.

I decided to wait until the end of the month before doing anything, in case the data was used for generating monthly reports. I hoped that on January 31st Wacom would notice that their graphs were broken and bring their system back online.

On February 3rd I checked in and was elated at what I saw:

I had no idea who Rick was, but I was glad he was back. Wacom were illegitimately siphoning off my personal data again, and I couldn’t be happier. I grabbed some better screenshots, fixed some grammar, and hit publish. The rest is history.

New - send me your privacy abuse tipoffs

Disclaimer: I haven’t asked Wacom for comment about this story because I’m not a journalist and I don’t know how to do that. I don’t believe I’ve got anything important wrong, however.

Chapter 1: The discovery

I have a Wacom drawing tablet. I use it to draw cover illustrations for my blog posts, such as this one:

Last week I set up my tablet on my new laptop. As part of installing its drivers I was asked to accept Wacom’s privacy policy.

Being a mostly-normal person I never usually read privacy policies. Instead I vigorously hammer the “yes” button in an effort to reach the game, machine, or medical advice on the other side of the agreement as fast as possible. But Wacom’s request made me pause. Why does a device that is essentially a mouse need a privacy policy? I wondered. Sensing skullduggery, I decided to make an exception to my anti-privacy-policy-policy and give this one a read.

In Wacom’s defense (that’s the only time you’re going to see that phrase today), the document was short and clear, although as we’ll see it wasn’t entirely open about its more dubious intentions (here’s the full text). In addition, despite its attempts to look like the kind of compulsory agreement that must be accepted in order to unlock the product behind it, as far as I can tell anyone with the presence of mind to decline it could do so with no adverse consequences.

With that attempt at even-handedness out the way, let’s get kicking.

In section 3.1 of their privacy policy, Wacom wondered if it would be OK if they sent a few bits and bobs of data from my computer to Google Analytics, “[including] aggregate usage data, technical session information and information about [my] hardware device.” The half of my heart that cares about privacy sank. The other half of my heart, the half that enjoys snooping on snoopers and figuring out what they’re up to, leapt. It was a disjointed feeling, probably similar to how it feels to get mugged by your favorite TV magician.

Wacom didn’t say exactly what data they were going to send themselves. I resolved to find out.

Chapter 2: Snooping on the snoopers

I began my investigation with a strong presumption of chicanery. I was unable to imagine the project kickoff meeting in which Wacom decided to bundle Google Analytics with their device, which - remember - is essentially a mouse, but managed to restrain themselves from also grabbing some deliciously intrusive information while they were at it. I Googled “wacom google analytics”. There were a couple of Tweets and Reddit posts made by people who had also read Wacom’s privacy policy and been unhappy about its contents, but no one had yet tried to find out exactly what data Wacom were grabbing. No one had investigated Wacom’s understanding of the phrase “aggregate usage data” or whether it was anywhere near that of a reasonable person.

I told my son to clear my schedule. He bashed two wooden blocks together in understanding, encouragement, and sheer admiration.

In order to see what type of data Wacom was exfiltrating from my computer, I needed to snoop on the traffic that their driver was sending to Google Analytics. The most common way to do this is to set up a proxy server on your computer (I usually use Burp Suite). You tell your target program to send its traffic through your proxy. Your proxy logs the data it receives, and finally re-sends it on to its intended destination. When the destination sends back a response, the same process runs in reverse.

+-------------------------------+

|My computer |

| |

| +------+ +------+ | +---------+

| |Wacom +------->+Burp +-------->+Google |

| |Driver+<-------+Suite +<--------+Analytics|

| +------+ +-+----+ | +---------+

| | Log requests and responses

| v |

| /track?data=... |

| |

+---------------------+---------+

Some applications, like web browsers, co-operate very well with proxies. They allow users to explicitly specify a proxy for them to to send their traffic through. However, other applications (including the Wacom tablet drivers) provide no such conveniences. Instead, they require some special treatment.

Chapter 3: Wireshark

I started with a simple approach that was unlikely to work but was worth a try. I opened Wireshark, a program that watches your computer’s network traffic. I wanted to use Wireshark to view the raw bytes that the Wacom driver was sending to Google Analytics. If Wacom was sending my data over unencrypted HTTP then I’d immediately be able to see all of its gory details, no extra work required. On the other hand, if Wacom was using encrypted TLS/HTTPS then I would be foiled. The traffic would appear as garbled nonsense that I would be unable to decrypt, since I wouldn’t know the keys used to encrypt it. I closed any noisy, network-connecting programs to reduce the chatter on the line, pressed Wireshark’s record button, and held onto my hat.

Unfortunately, no unencrypted HTTP traffic appeared; only encrypted, garbled TLS. But there was good news amidst this setback. Wireshark also picks up DNS requests, which are used to look up the IP address that corresponds to a domain. I saw that my computer was making DNS requests to look up the IP address of www.google-analytics.com. The DNS response was coming back as 172.217.7.14, and lots of TLS-encrypted traffic was then heading out to that IP address. This meant that something was indeed talking to Google Analytics.

I switched tactics and fired up Burp Suite proxy.

Chapter 4: Burp Suite

I now had two problems. First, I needed to persuade Wacom to send its Google Analytics traffic through Burp Suite. Second, I needed to make sure that Wacom would then complete a TLS handshake with Burp. To solve the first problem, I configured my laptop’s global HTTP and HTTPS proxies to point to Burp Suite. This meant that every program that respected these global settings would send its traffic through my proxy.

Happily, it turned out that Wacom did respect my global proxy settings - my proxy quickly started logging “client failed TLS handshake” messages.

This brought me to my second problem. Since Wacom was talking to Google Analytics over TLS, it required the server to present a valid TLS certificate for www.google-analytics.com. As far as Wacom is concerned, my proxy was now the server that it is talking to, not Google Analytics itself. This meant that I needed my proxy to present a certificate that Wacom would trust.

(Burp must present a valid cert for www.google-analytics.com)

|

+---------------------|---------+

|My computer | |

| v |

| +------+ +------+ | +---------+

| |Wacom +------->+Burp +-------->+Google |

| |Driver+<-------+Suite +<--------+Analytics|

| +------+ +-+----+ | +---------+

| | Log requests and responses

| v |

| /track?data=... |

| |

+---------------------+---------+

The most difficult part of presenting such a certificate is that it needs to be cryptographically signed by a certificate authority that the program trusts. Burp Suite can generate and sign certificates for any domain, no problem, but since by default no computer or program trusts Burp Suite as a certificate authority, the certificates it signs are rejected (I’ve written much more about TLS and HTTPS here and here).

Once again, the process of persuading a web browser to trust Burp’s root certificate is well-documented, but for a thick application like Wacom I’d need to do something slightly different. I therefore used OSX’s Keychain to temporarily add Burp’s certificate to my computer’s list of root certificates.

I assumed that Wacom would load its list of root certificates from my computer, and that by adding Burp to this list, Wacom would start to trust Burp and would complete a TLS handshake with my proxy.

I sat and waited. I watched Wireshark and Burp at the same time. If Wacom failed to connect to Burp, I’d see this failure in Wireshark. I was quite excited.

Nothing happened.

I wondered if the data dumping was triggered by a timer, or by some particular activity, or by both. I tried drawing something using my Wacom tablet. Still nothing. I plugged and unplugged it. Nothing. Then I went into the Wacom Driver Settings and restarted the driver.

Everything happened.

When I restarted the Wacom driver, rather than lose all the data it had accumulated, the driver fired off everything it had collected to Google Analytics. This data materialized in my Burp Suite. I took a look. My heart experienced the same half-down-half-up schism as it had half an hour ago.

Some of the events that Wacom were recording were arguably within their purview, such as “driver started” and “driver shutdown”. I still don’t want them to take this information because there’s nothing in it for me, but their attempt to do so feels broadly justifiable. What requires more explanation is why Wacom think it’s acceptable to record every time I open a new application, including the time, a string that presumably uniquely identifies me, and the application’s name.

Chapter 5: Analysis

I suspect that Wacom doesn’t really think that it’s acceptable to record the name of every application I open on my personal laptop. I suspect that this is why their privacy policy doesn’t really admit that this is what that they do. I imagine that if pressed they would argue that the name of every application I open on my personal laptop falls into one of their broad buckets like “aggregate data” or “technical session information”, although it’s not immediately obvious to me which bucket.

It’s well-known that no one reads privacy policies and that they’re often a fig leaf of consent at best. But since Wacom’s privacy policy makes no mention of their intention to record the name of every application I open on my personal laptop, I’d argue that it doesn’t even give them the technical-fig-leaf-right to do so. In fact, I’d argue that even if someone had read and understood Wacom’s privacy policy, and had knowingly consented to a reasonable interpretation of the words inside it, that person would still not have agreed to allow Wacom to log and track the name of every application that they opened on their personal laptop.

Of course, I’m not a lawyer, and I assume that whoever wrote this privacy policy is.

Wacom’s privacy policy does say that they only want this data for product development purposes, and on this point I do actually believe them. This might be naive, since who knows what goes on behind the scenes when large troves of data are involved. Either way, while I do understand that product developers like to have usage data in order to monitor and improve their offerings, this doesn’t give them the right to take it.

I care about this for two reasons.

The first is a principled fuck you. I don’t care whether anything materially bad will or won’t happen as a consequence of Wacom taking this data from me. I simply resent the fact that they’re doing it.

The second is that we can also come up with scenarios that involve real harms. Maybe the very existence of a program is secret or sensitive information. What if a Wacom employee suddenly starts seeing entries spring up for “Half Life 3 Test Build”? Obviously I don’t care about the secrecy of Valve’s new games, but I assume that Valve does.

We can get more subtle. I personally use Google Analytics to track visitors to my website. I do feel bad about this, but I’ve got to get my self-esteem from somewhere. Google Analytics has a “User Explorer” tool, in which you can zoom in on the activity of a specific user. Suppose that someone at Wacom “fingerprints” a target person that they knew in real life by seeing that this person uses a very particular combination of applications. The Wacom employee then uses this fingerprint to find the person in the “User Explorer” tool. Finally the Wacom employee sees that their target also uses “LivingWith: Cancer Support”.

Remember, this information is coming from a device that is essentially a mouse.

This example is admittedly a little contrived, but it’s also an illustration that, even though this data doesn’t come with a name and social security number attached, it is neither benign nor inert.

Chapter 6: Conclusion

In some ways it feels unfair to single out Wacom. This isn’t the dataset that’s going to complete the embrace of full, totalitarian surveillance capitalism. Nonetheless, it’s still deeply obnoxious. A device that is essentially a mouse has no legitimate reasons to make HTTP requests of any sort. Maybe Wacom could hide in the sweet safety of murky territory if they released some sort of mobile app integration or a weekly personal usage report that required this data, but until then I’m happy to classify them as an obligingly clear case of nefariousness.

Nonetheless, I’m not about to incinerate my Wacom tablet and buy a different one. These things are expensive, and privacy is hard to put a price on. If you too have a Wacom tablet (presumably this tracking is enabled for all of their models), open up the “Wacom Desktop Center” and click around until you find a way to disable the “Wacom Experience Program”. Then the next time you’re buying a tablet, remember that Wacom tries to track every app you open, and consider giving another brand a go.

Epilogue

I finished the first draft of this article three weeks ago. I set up Burp Suite proxy again so that I could grab some final screenshots of the data that Wacom was purloining. I restarted the Wacom driver, as per usual. But nothing happened. Wacom weren’t illegitimately siphoning off my personal usage data any more.

The bastards.

I contemplated pretending I hadn’t seen this and publishing my post anyway. Then I contemplated publishing it with an additional coda explaining this latest development. However, the title “Wacom drawing tablets used to track the name of every application that you open but now seem to have stopped for some reason” didn’t feel very snappy. I decided to do some more investigating.

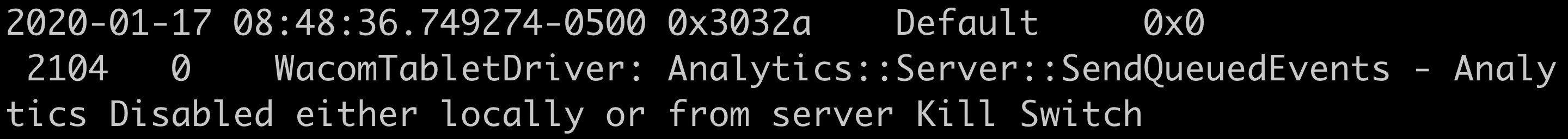

I had previously noticed that, before sending data to Google Analytics, the Wacom driver sent a HEAD request to the URL http://link.wacom.com/analytics/analytics.xml. I hadn’t been able to work out why, and until now I hadn’t thought much of it. However, now Wacom was responding to this request with a 404 “Not Found” status code instead of 200 “OK”. I realized that the request must be some kind of pre-flight check that allowed Wacom to turn off analytics collection remotely without requiring users to install a driver update. Now that the request was failing, Wacom were not sending themselves my data.

I dug around in the driver’s logfile and found the following snippet that confirmed my suspicions:

I wondered if Wacom had gotten wise to what I was up to and panic-disabled their tracking. This seemed unlikely, although the timing was rather coincidental. I decided that Wacom had probably simply made a boneheaded mistake and accidentally broken their own command-and-control center. I impatiently waited for them to realize their goof and bring their data exfiltration operation back online. I contemplated emailing Wacom to alert them to their problem, but couldn’t come up with a sufficiently innocuous way of doing so.

I decided to wait until the end of the month before doing anything, in case the data was used for generating monthly reports. I hoped that on January 31st Wacom would notice that their graphs were broken and bring their system back online.

On February 3rd I checked in and was elated at what I saw:

I had no idea who Rick was, but I was glad he was back. Wacom were illegitimately siphoning off my personal data again, and I couldn’t be happier. I grabbed some better screenshots, fixed some grammar, and hit publish. The rest is history.

New - send me your privacy abuse tipoffs