Programming Projects for Advanced Beginners #3a: Tic-Tac-Toe AI

09 Oct 2018

This is a programming project for Advanced Beginners. If you’ve completed all the introductory programming tutorials you can find and want to start sharpening your skills on something bigger, this project is for you. You’ll get thrown in at the deep end. But you’ll also get gentle reminders on how to swim, as well as some new tips on swimming best practices. You can do it using any programming language you like, and if you get stuck I’ll help you out over email, Twitter or Skype.

NEW

Subscribe to my new "Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners"

newsletter to receive concise weekly emails containing specific,

real-world ways to make your code cleaner and more professional.

Each week I review code sent to me by one of my readers. I highlight

the things that I like, discuss the

things that I think could be better, and offer suggestions for how

the author could make their code cleaner and easier to work with.

Subscribe now to receive these invaluable improvements in your inbox

every week, completely free.

You’re going to build artificial intelligences (AIs) that play Tic Tac Toe. You’ll battle different algorithms against each other, challenge your friends to build their own, and ultimately develop an unbeatable, perfect Tic Tac Toe AI.

You’ll learn how to break down large, intimidating projects into smaller, manageable pieces. You’ll learn how to separate your code into independent chunks that are each responsible for 1 thing. You’ll learn how to solve problems using the simplest code you can get away with, and how to refactor your work to handle more complex problems as they emerge. You’ll learn how to not feel bad when you write throwaway test code, and you’ll learn to apply these invaluable principles to your future projects.

And you’ll become unbeatable at Tic-Tac-Toe.

Introduction

The project is divided into 2 parts. In part 1 we’re going to build a command-line Tic-Tac-Toe game that allows 2 human players to face off against each other by typing their moves into the terminal. In part 2 we’ll replace the humans with AIs. This substitution will be surprisingly simple. There’s a metaphor in that somewhere.

The project is split up in this way because building a perfect Tic-Tac-Toe AI is a difficult, monolithic task. It’s a colossal boulder of a challenge, with no handholds or clues for how to work with it. When confronted with a task like this, the first thing you should do is cut it up into smaller, more manageable chunks. This allows you focus on a single chunk at a time, temporarily shunting all the others to one side.

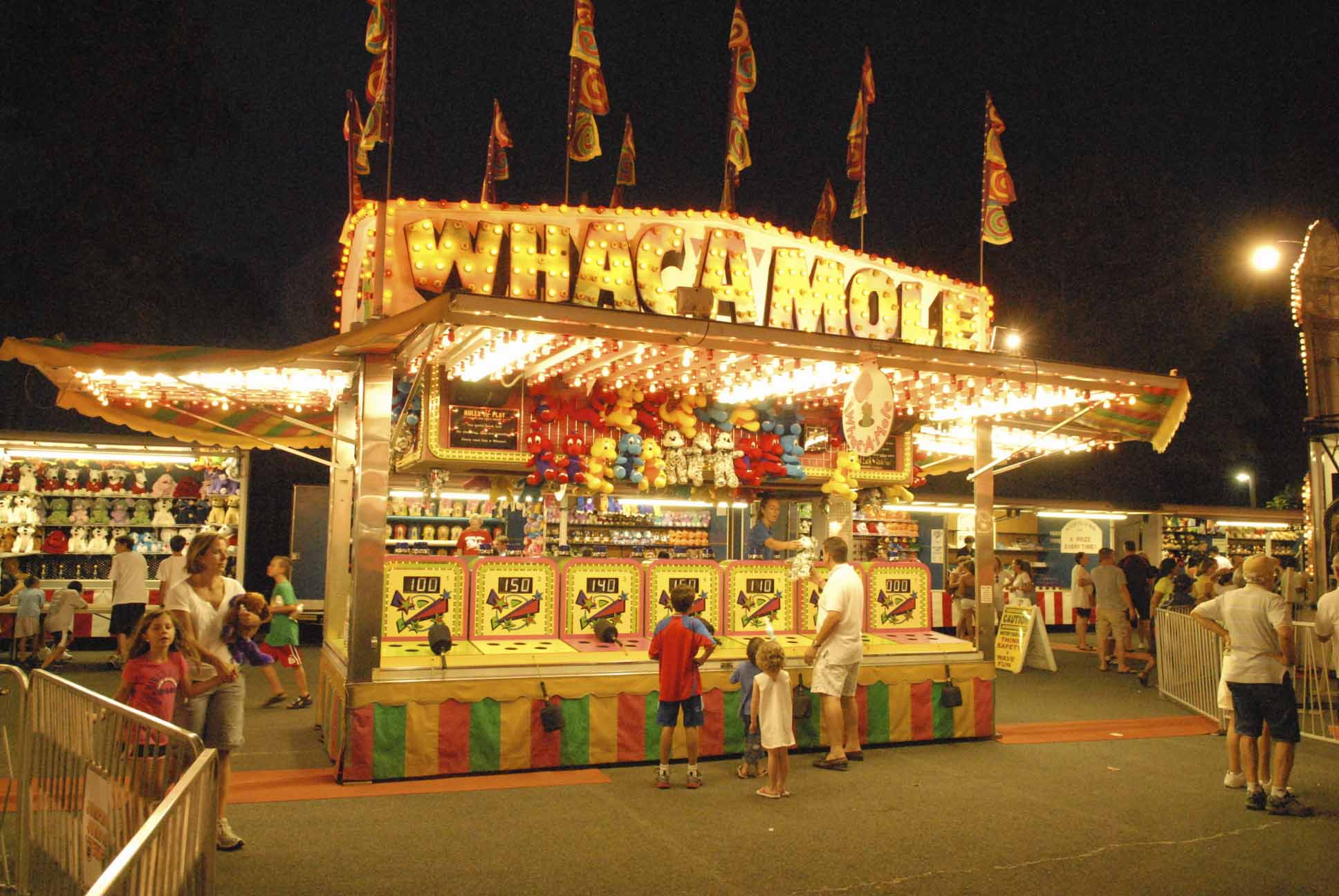

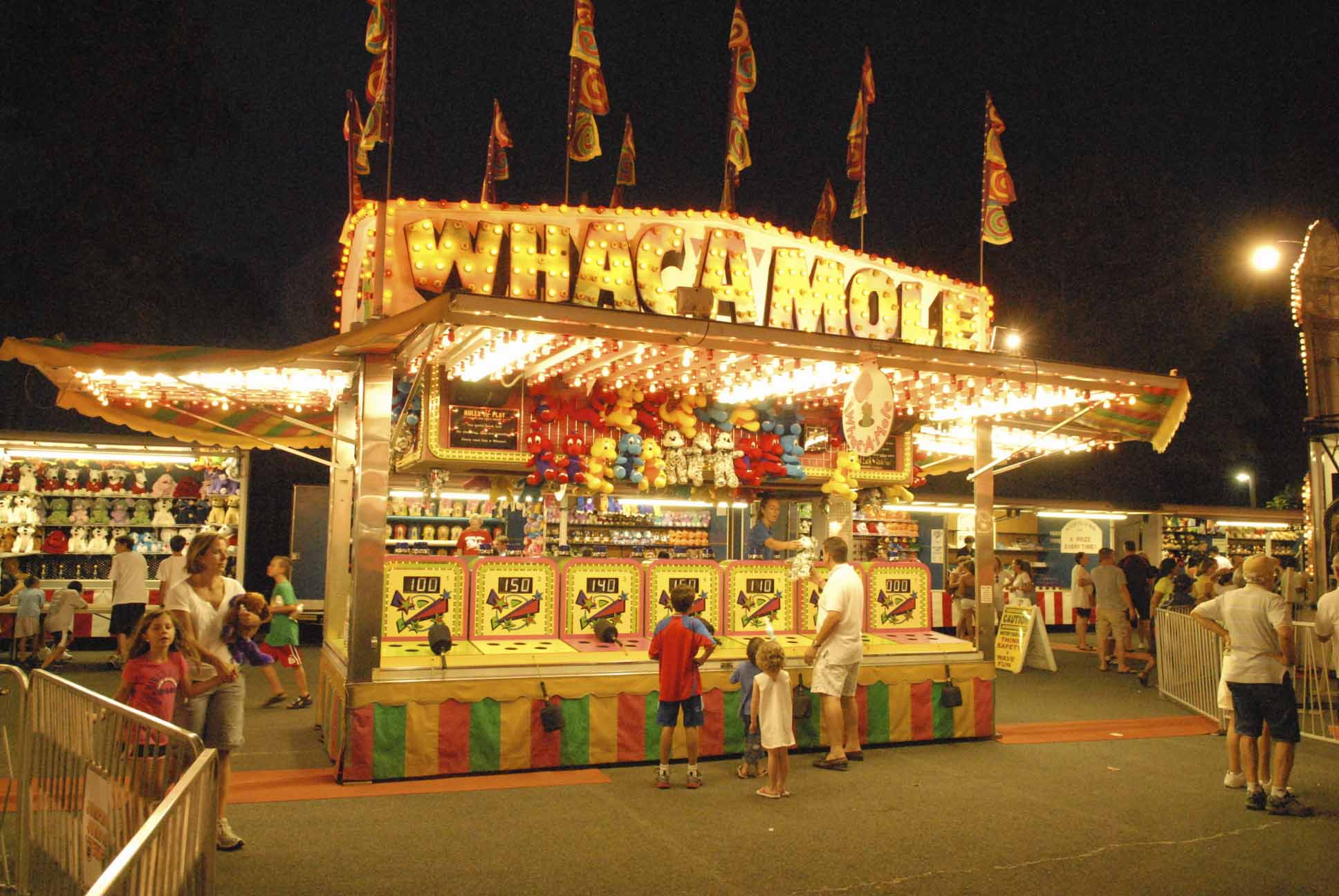

You may have played the game “Whac-A-Mole” at fun fairs. Moles pop up randomly out of 10 or 20 different holes, and your job is to bash them on the head and send them straight back to hell. The game is difficult and therefore profitable for funfair owners because there are so many different places that the moles could pop out of. This is what working on a large program can be like. You fix one problem, but this causes another mole to pop up on the other side of the program. You fix that one too, but then 3 more moles raise their ugly heads and the buzzer goes off and you lose yet again.

If you build your code out of small, isolated pieces that you can pick off one at a time, then it’s as though you’re playing Whack-A-Mole with only one hole and only one mole. This is why they call me “The Mole Killer.”

Let’s try breaking down our Tic-Tac-Toe AI project into easily bashable pieces. We’ll start by cleaving it into a few smaller sub-projects:

- Build a Tic-Tac-Toe game or “engine” that allows human players to play against each other

- Plug AIs into our Tic Tac Toe engine

- Repeatedly play AIs against each other to see which of them is the best

This is a reasonable start. “Build a Tic-Tac-Toe engine” is a smaller task than “build a perfect Tic-Tac-Toe AI”. It’s already much easier to think about. But it’s still too big for my liking. Fortunately, we don’t have to get the chunks perfectly sized first time round. We can keep chipping away at them until we have a pile of well-formed tasks that are each small enough to start working on.

Code skeletons

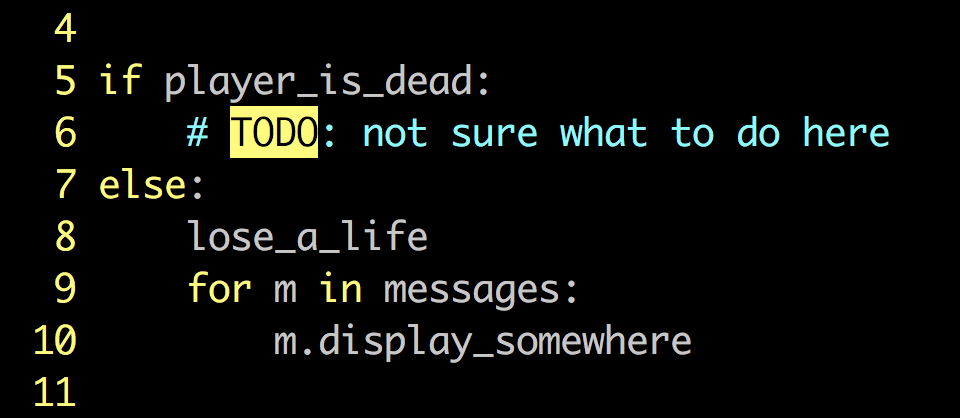

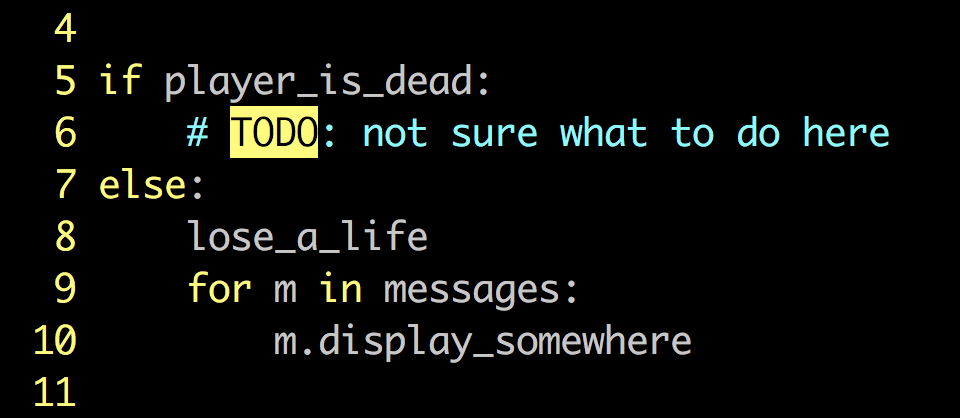

One way to start breaking down a big program is to make a rough sketch of its high-level code, which we’ll call a “skeleton program”. Jotting down a skeleton helps you work out what the different components of the program are and how they might all fit together. Skeletons are usually messy, poorly formatted and consist mostly of syntax errors. But the point of them isn’t to produce valid code. The point is to better understand the tasks in front of us.

You will often find that writing a skeleton helps to tame a project that had previously seemed daunting and unapproachable. Once you’ve broken off a few pieces and have realized that they aren’t as spooky as you first thought - “well if I want to make Tic-Tac-Toe then I’ll obviously need a 3x3 board of some sort” - it becomes much easier to keep breaking off more pieces until there’s nothing left to do.

When you’re writing a skeleton and you come to a medium-sized piece of logic like “figure out whether someone has won the game”, don’t spend too much time worrying about how to flesh it out. A task like this is a perfectly sized “milestone” that we can work on properly later. For now, write a placeholder function to come back to (in this case, something like get_winner). Think briefly about the interface of this function - the arguments it will need, and the data it will return.

A code skeleton for Tic-Tac-Toe

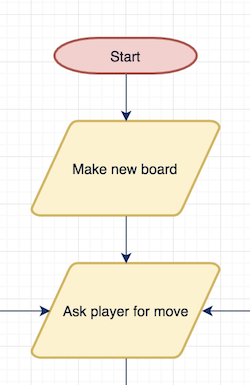

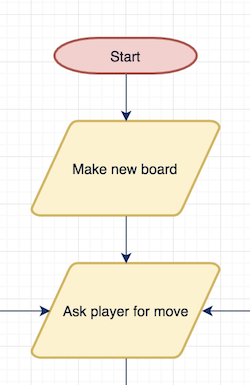

Let’s try sketching out a skeleton for our Tic-Tac-Toe engine. Before reading any further, spend a few minutes sketching one on your own. If you’re having trouble, start by making a list of as many of the individual challenges involved in making a Tic-Tac-Toe game as you can. Don’t worry about arranging them or putting them in an order. You could also try temporarily forgetting about code completely, and draw a flow chart that describes the rules for playing Tic-Tac-Toe.

Here’s the skeleton that I came up with:

board = new_board()

# Loop through turns until the game is over

loop forever:

# TODO: hmm I'm not sure how best to do this

# right now. No problem, I'll come back later.

current_player = ???

# Print the current state of the board

render(board)

# Get the move that the current player is going

# to make.

move_co_ords = get_move()

# Make the move that we calculated above

make_move(board, move_co_ords, current_player)

# Work out if there's a winner

winner = get_winner(board)

# If there is a winner, crown them the champion

# and exit the loop.

if winner is not None:

print "WINNER IS %s!!" % winner

break

# If there is no winner and the board is full,

# exit the loop.

if is_board_full(board):

print "IT'S A DRAW!!"

break

# Repeat until the game is over

Looking over this skeleton, I notice that it is made up of about 6 main components:

new_boardrenderget_movemake_moveget_winneris_board_full

Now these are some well-sized chunks of work. We can work on each of them in almost total isolation, without having to worry about the others. When we’re calculating whether our game has a winner yet (get_winner), we can completely forget about how it is actually played (get_move, make_move). Once we’ve finished writing each of these components and have glued them all together, we’ll have finished our Tic-Tac-Toe engine. After all, if you take the right body parts, stitch them onto each other and apply electricity, you’ve got yourself a fully-functional Frankenstein’s monster.

Our initial task list is neither exhaustive nor binding. When writing a big program you will always encounter new problems that you didn’t anticipate. You will always change your mind about how to arrange several limbs of your skeleton, but adaptation becomes much easier when you have an actual plan that you can adapt. We will use the above task list as “milestones” - checkpoints that allow us to constantly verify that we are on the right track.

Run code frequently

We’re going to run our code very frequently; at an absolute minimum once every time we complete a milestone. This will make bugs easy to locate and destroy, because there will be very few places in which they can hide. If our program is broken, but was working 10 minutes ago, then I’ll bet you pesos to pizza that there’s a bug holed up in the couple of lines we wrote during those fateful 10 minutes.

We could instead write hundreds of lines of code in one go before finally running our program once and crossing our fingers. But whilst high-risk moments of truth make for a good movie, they make for terrible software. In a good development process, the hero (that’s you) tests their work frequently. They use a small-steps approach in order to uncover bugs quickly. They have a better understanding of the internals of their code because of this, and can frequently adjust and course-correct their plans. They might not produce a thrilling box office hit, but they will ensure that the software that powers the box office actually works.

Building a Tic-Tac-Toe engine

We’re now ready to grind down our first, appropriately-sized milestone - making the Tic-Tac-Toe board.

Remember that if you ever need a hint, I’ve written an example program that you can take inspiration from.

1. Representing the board

We’re going to start by making a “data structure” that stores the state of the game board. Tic-Tac-Toe is played on a 3x3 grid, and in code, grids are often represented using nested lists, or “lists of lists”. If you haven’t come across this idea before, read the explanation of lists of lists in part 1 of my Game of Life project.

[

['X', None, 'O'],

['O', None, None],

[None, 'X', 'X']

]

Each element in our list-of-lists will represent a square on the board. In each sqaure we will need to be able to represent the 3 possible states - O, X and empty. I suggest representing O and X using the characters O and X, and an empty square using None or nil or however it is that your programming language represents “nothing”.

Your first task is to write a new_board function that takes in 0 arguments and returns an empty, 3x3 grid. Test that your function works with a simple print-statement.

print new_board()

=> [[None, None, None], [None, None, None], [None, None, None]]

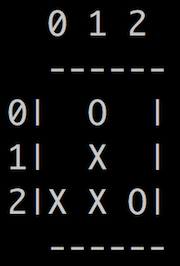

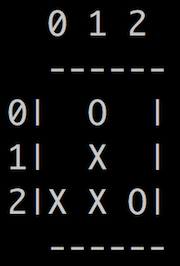

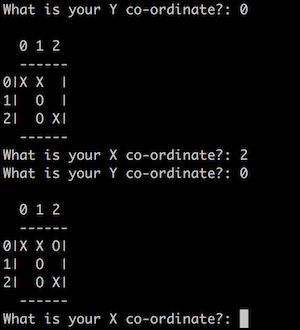

2. Print the board

Basic print-statements are fine for debugging, but our players deserve something more refined. In this milestone we’re going to write a function whose only job is to pretty-print our board to the terminal in a form that is useful to humans.

Write a render function that takes in 1 argument - a Tic-Tac-Toe board - and prints it to the terminal. This function does not need to return anything. You can format the board however you like; I personally found it useful to add co-ordinate markers around the edge to make it easier for human players to reference specific squares.

Test your render function by using it to print some dummy boards. Construct these boards by generating an empty board using new_board and adding moves to it manually.

board = new_board()

board[0][1] = ‘X'

board[1][1] = ‘O'

render(board)

=>

0 1 2

------

0| |

1|X O |

2| |

------

We’re going to delete this test code almost immediately, but that’s fine, code is free. Writing throwaway scripts like this isn’t cheating - it’s just good practice.

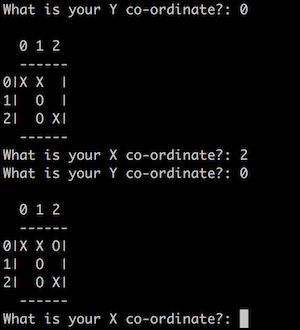

3. Get player input

Now that we’ve got a board and a way to display it, we’re ready to start playing.

In this milestone we’re going to work out how to ask our human players to input their moves. Because we understand the extreme power of focussing on one thing at a time, we’re not yet going to worry about using these moves to update the board. Once again, this temporary shortcut is not cheating.

We could ask our players to input their moves in many different formats. I like asking for X and Y co-ordinates, because this maps well onto our grid data structure. But you could also assign each square a number from 1 to 9, or a word, or a letter.

1 O 3

4 X 6

O 8 9

The decision of how to ask our users for input is very low-stakes, and it doesn’t matter much if we change our minds later. This is not because user interfaces aren’t important - they are a vital part of a useful, functional program. Rather, the decision of how to ask our users for input is very low stakes because it is so easy for us to change, even if we’ve already finished the rest of our program. If we do change our minds then we should only have to update the section of our code that asks our players for input. The other components of our program should not have to care about this change. Once we have turned a player’s input into a move co-ordinate, the code that uses this co-ordinate to update the board shouldn’t have to know or concern itself with where the co-ordinate came from. This is a concept known as modularity - more on which in future projects.

You should still strive to make the best decisions you can. But you should also make sure to understand when a decision is binding, when a decision is easily reversible, and how you can restructure your code so that a decision becomes easily reversible. Think about the extent to which other parts of your program rely and care about your decisions. Would it be awkward for them if you changed your mind later? For example, it’s far more important that we cast-iron decide on our tic-tac-toe board’s shape than on its size. Changing our board from square to hexagonal would have far more knock-on effects than changing its height from 3 squares to 4.

Write a get_move function that takes 0 arguments, and returns the co-ordinates of the player’s chosen move as a 2-element tuple or array (one element each for the x and y co-ordinates), or whatever works best in your language.

Test it by running it and printing its output:

move_coords = get_move()

=> What is your move's X co-ordinate?: 1

=> What is your move's Y co-ordinate?: 2

print move_coords

=> (1, 2)

4. Execute moves

Now that our players can input their moves, it’s time for us to use those moves to update the board. We’re still not going to worry about whether either of our players has won. You can probably guess why.

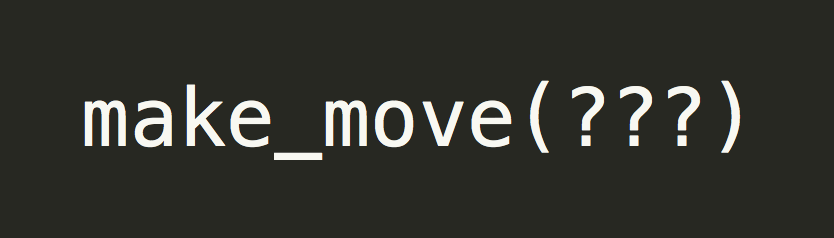

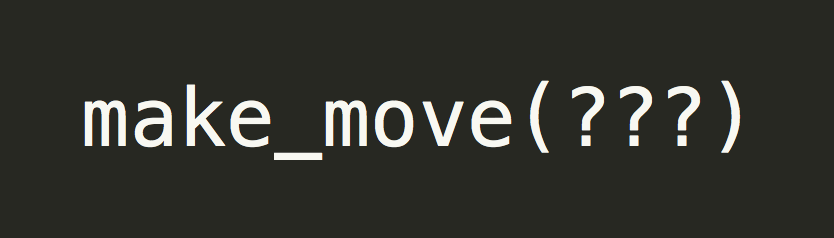

In this milestone you’re going to write a function called make_move. As the name suggests, this function will execute a Tic-Tac-Toe move by updating the board. make_move will not print the board; printing is the job of our render function from part 2. Instead, we’ll use make_move to update the board, then separately pass the updated board into render for printing.

Before going any further, think about what arguments make_move will need to take in in order to update the board.

The answer is that make_move will need 3 arguments:

- The board

- The co-ordinates of the move

- The player who is making the move (so that

make_move knows whether to insert an O or an X into the board)

Return values and mutation

We have a choice about what our make_move function returns. It could either:

- Return a new board with the given move added:

new_board = make_move(old_board, (1, 1), 'X')

# `old_board` still represents the old position

# `new_board` is equivalent to `old_board` PLUS an 'X' at (1,1)

- Or return nothing, and update (or mutate) the board that it was given:

make_move(board, (1, 1), 'X')

# `board` has been mutated directly to add an 'X' at (1,1)

You should usually be wary of mutating a function’s arguments. Mutation can be surprising and unexpected, and can make for subtle, hard-to-diagnose bugs. It’s often much clearer to leave a function’s arguments unchanged, and to instead return new data representing a new state.

Mutation can sometimes be a defensible design choice. However, having seen the future, I know that this project will be easier if we steer clear of it. We should leave the board that make_move is given untouched, and return a brand new one instead.

When I was writing the first version of my code for this project, I wrote make_move using mutation. It took me a while to discover the problems with this decision, but, thanks to modularity, once I did I was able to come back and change my design with very little invasive surgery.

If the idea of mutation doesn’t make sense yet, don’t worry. It’s a subtle concept, and a thorough understanding of it is not necessary for this project.

You’re now ready to write a make_move function that takes in 3 arguments - the board, the move co-ordinates, and the player making the move. It should not mutate the board that it is given, and should return a new board, with the new move made.

Test your work by making some moves.

board = new_board()

move_coords_1 = (2, 0)

board = make_move(board, move_coords_1, "X")

render(board)

move_coords_2 = (1, 1)

board = make_move(board, move_coords_2, "O")

render(board)

Error handling - an edge-case

How does your make_move function deal with the following situation? How should it deal with it?

board = new_board()

move_coords = (2, 0)

board = make_move(board, move_coords, "X")

board = make_move(board, move_coords, "O")

=> ???

I think that the best thing to do when make_move is given an illegal move is for it to panic and raise an exception. I want make_move to be responsible only for executing moves, and absolutely nothing else. This means that its “contract” with the rest of the program is that the moves it is given had better all be legal, or else it’s going to have a freak out.

If we decide that we want to allow a player who makes an illegal move to retry with a different choice, then I would want us to make a separate function whose job it is to validate moves (maybe called is_valid_move). This might look something like:

move_coords = None

while True:

move_coords = get_move()

if is_valid_move(board, move_coords):

break

else:

print "Invalid move, try again"

board = make_move(board, move_coords, player)

make_move still freaks out if we give it bad input, but we’ve added some extra code to ensure that we don’t.

Update your make_move function to raise an exception if it’s given an illegal move. Make sure that it works.

board = new_board()

move_coords = (2, 0)

board = make_move(board, move_coords, "X")

board = make_move(board, move_coords, "X")

=> Exception: "Can't make move (2, 0), square already taken!"

5. Combining our work so far

So far we have written several functions that together can:

- Make a new board

- Print a board

- Ask a human player for a move

- Update a board with a move

Let’s join these components up to make a prototype program that allows the O and X players to take alternate moves until the board fills up. When the board fills up the program will probably crash. This is fine.

This is not the dummy’s approach to software development. I’m not blowing smoke at you - “you’re only an advanced beginner, it’s OK if your programs crash sometimes and don’t do everything that they’re meant to.” My own version of Tic-Tac-Toe started life as an incomplete program that broke a lot. Then I kept working on it, adding one feature and a few lines at a time, until it had stopped breaking and was complete.

Start by looking back at our code skeleton from the introduction. Pick out the bits that you need, and plug in our actual-code-so-far. You’ll notice that we haven’t yet written any code that will alternate moves between O and X - see if you can write this yourself. There are several reasonable ways to do it, and my example code is there if you need it.

Once you’ve got your sort-of-Tic-Tac-Toe program working, you’re ready to move on.

6. Check for winners

Hope and dreams and games of Tic-Tac-Toe are won or lost by one player getting 3 Os or Xs in a straight line. It’s our job to identify victories and declare champions. Stop and think for a minute or two about how to teach a computer to work out whether either player has won a game of Tic-Tac-Toe.

When I was thinking about this, I asked myself “how does a human work out whether either player has won a game of Tic Tac Toe?” Asking “how would a human do this?” can be a very useful way to design programs. Often (not always), a computer will do things in the same way as a human would, only much, much faster. In this case, the answer I came up with was “a human would look at every possible line of 3 grid squares, and check whether any of them contain all Os or all Xs.”

Write a get_winner function that takes take 1 argument - a board - and returns the ID of the player that has won (O or X), or None if no one has won yet. I’d suggest that you structure your function like this:

- Build a list of all the lines on the board - columns, rows and diagonals (eg. -

[[O, X, None], [X, O, X], # etc...)

- For each line in this list, check whether it contains all Os or all Xs. If yes, return the character of the winning player (

O or X). If no, continue onto the next line

- If none of the lines on the board are winners, return

None or nil to indicate that no one has won yet

Test your function with some practice boards:

board_1 = [

['X', 'X', 'O'],

['O', 'X', None]

['O', 'O', 'X']

]

get_winner(board_1)

=> 'X'

board_2 = [

['X', 'X', 'O'],

['O', None, 'X']

['O', 'O', 'X']

]

get_winner(board_2)

=> None

Bonus points are available for writing “unit tests” like in section 3 of my Game of Life project. These tests will help ensure that you have covered every possible edge-case, and that don’t accidentally break your code in the future.

Once you are confident that your get_winner function works, plug it into the rest of your program. Your program should still allow players to alternate taking turns, but now it should also end the game when one player makes a line of 3.

Then there’s only one thing left to do.

7. Check for a draw

Not all games of Tic-Tac-Toe end in a victory. If both players are evenly matched then a game may end in a hard-fought draw. Figure out how to add this logic to your program.

Since this is the final piece of this project, that’s all the advice I’ll give you. Walk yourself through the problem step-by-step. Check my example code if you get stuck.

8. Keep testing

Keep testing your Tic-Tac-Toe engine by playing practice games against yourself and your friends. Fix bugs (there will be bugs), until no bugs remain.

9. Final task - say hi!

You now have a fully-working, bug-free Tic-Tac-Toe engine. Congratulations! After pausing to pat yourself on the back, send me an email to let me know that you’ve finished! I’d love to hear from you. Have a go at my other programming projects for advanced beginners as well - ASCII art and Game of Life. Most importantly, sign up for my mailing list (see the bottom of the page) to find out when the next part of this project is released and you can start work on your unbeatable Tic-Tac-Toe AI.

Once you’ve completed these final tasks, compose yourself and venture boldly into the extensions section below, or straight on to part 2.

Extensions

This section contains several extension projects that build on top of our Tic-Tac-Toe code so far. Pick and choose the ones that you like the look of, and dream up your own, entirely new ones. Because these are extension projects, I’ll be giving you far fewer tips and pointers. Instead, you should be your own guide and walk yourself through them using the techniques and strategies that we used to build our main Tic-Tac-Toe game. Start by breaking up the tasks into small pieces. Work on one piece at a time and run your code as often as you can. Don’t be afraid of writing test code that you quickly throw away, and don’t be afraid of writing programs that only do 50, 25, or even 1 percent of what you want them to eventually be capable of.

Before starting work on the extensions, save a copy of your code. We’re going to need it for the next section of the main project - “Making a perfect TicTacToe AI”. You can save a copy by either duplicating the file, or using “git” to check out a new branch. Both approaches are totally fine, and don’t feel bad if you haven’t come across git before.

Extension 1: Build an “AI” player that makes random moves

Add the option for a single human player to play against an AI computer player. This AI player should start by only making random (legal) moves. We’ll look at how to make them smarter in the next project. If you want to get a head start on making your AI player smarter then go wild.

Extension 2: Improve the user experience

Allow each player to enter their name. Print out random celebration lines when someone wins. Add color to the printouts. Use your imagination.

Extension 3: Play different games

There are lots of games that are like Tic Tac Toe, only better and more complex. Look up Connect 4, and use the techniques you learned in this project to write an engine for it it. Steal shamelessly from your code in this project.

Try changing the rules of Tic Tac Toe too. Make the board bigger, add a third player, make the board a weird shape.

Extension 4: Networked gaming

Allow your players to play on different computers, over a local network. Each computer should run its own copy of your program, and they should send their moves to each other via TCP.

Extension 5: Leagues, statistics and databases

Keep track of players and their results. Use a database to store match results, and add tools to print out league tables. Add a username and password login system so that players can’t impersonate each other - make sure to look up how to securely store passwords first (keywords - hashing and salting).

Running a networked Tic Tac Toe league may feel like taking things Tic Tac Toe too far. But networks and league tables are not specific to Tic Tac Toe. In a future project we’re going to build the game “Tron” (like from the movie). Tic Tac Toe is fun, but Tron is awesome. You’ll be able to reuse a lot of your networking and results-tracking code from your Tic Tac Toe in your Tron.

See you in part 2, where we’ll ruin the noble game of Tic Tac Toe by building an AI that plays it perfectly.

This is a programming project for Advanced Beginners. If you’ve completed all the introductory programming tutorials you can find and want to start sharpening your skills on something bigger, this project is for you. You’ll get thrown in at the deep end. But you’ll also get gentle reminders on how to swim, as well as some new tips on swimming best practices. You can do it using any programming language you like, and if you get stuck I’ll help you out over email, Twitter or Skype.

Subscribe to my new "Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners" newsletter to receive concise weekly emails containing specific, real-world ways to make your code cleaner and more professional.

Each week I review code sent to me by one of my readers. I highlight the things that I like, discuss the things that I think could be better, and offer suggestions for how the author could make their code cleaner and easier to work with.

Subscribe now to receive these invaluable improvements in your inbox every week, completely free.

You’re going to build artificial intelligences (AIs) that play Tic Tac Toe. You’ll battle different algorithms against each other, challenge your friends to build their own, and ultimately develop an unbeatable, perfect Tic Tac Toe AI.

You’ll learn how to break down large, intimidating projects into smaller, manageable pieces. You’ll learn how to separate your code into independent chunks that are each responsible for 1 thing. You’ll learn how to solve problems using the simplest code you can get away with, and how to refactor your work to handle more complex problems as they emerge. You’ll learn how to not feel bad when you write throwaway test code, and you’ll learn to apply these invaluable principles to your future projects.

And you’ll become unbeatable at Tic-Tac-Toe.

Introduction

The project is divided into 2 parts. In part 1 we’re going to build a command-line Tic-Tac-Toe game that allows 2 human players to face off against each other by typing their moves into the terminal. In part 2 we’ll replace the humans with AIs. This substitution will be surprisingly simple. There’s a metaphor in that somewhere.

The project is split up in this way because building a perfect Tic-Tac-Toe AI is a difficult, monolithic task. It’s a colossal boulder of a challenge, with no handholds or clues for how to work with it. When confronted with a task like this, the first thing you should do is cut it up into smaller, more manageable chunks. This allows you focus on a single chunk at a time, temporarily shunting all the others to one side.

You may have played the game “Whac-A-Mole” at fun fairs. Moles pop up randomly out of 10 or 20 different holes, and your job is to bash them on the head and send them straight back to hell. The game is difficult and therefore profitable for funfair owners because there are so many different places that the moles could pop out of. This is what working on a large program can be like. You fix one problem, but this causes another mole to pop up on the other side of the program. You fix that one too, but then 3 more moles raise their ugly heads and the buzzer goes off and you lose yet again.

If you build your code out of small, isolated pieces that you can pick off one at a time, then it’s as though you’re playing Whack-A-Mole with only one hole and only one mole. This is why they call me “The Mole Killer.”

Let’s try breaking down our Tic-Tac-Toe AI project into easily bashable pieces. We’ll start by cleaving it into a few smaller sub-projects:

- Build a Tic-Tac-Toe game or “engine” that allows human players to play against each other

- Plug AIs into our Tic Tac Toe engine

- Repeatedly play AIs against each other to see which of them is the best

This is a reasonable start. “Build a Tic-Tac-Toe engine” is a smaller task than “build a perfect Tic-Tac-Toe AI”. It’s already much easier to think about. But it’s still too big for my liking. Fortunately, we don’t have to get the chunks perfectly sized first time round. We can keep chipping away at them until we have a pile of well-formed tasks that are each small enough to start working on.

Code skeletons

One way to start breaking down a big program is to make a rough sketch of its high-level code, which we’ll call a “skeleton program”. Jotting down a skeleton helps you work out what the different components of the program are and how they might all fit together. Skeletons are usually messy, poorly formatted and consist mostly of syntax errors. But the point of them isn’t to produce valid code. The point is to better understand the tasks in front of us.

You will often find that writing a skeleton helps to tame a project that had previously seemed daunting and unapproachable. Once you’ve broken off a few pieces and have realized that they aren’t as spooky as you first thought - “well if I want to make Tic-Tac-Toe then I’ll obviously need a 3x3 board of some sort” - it becomes much easier to keep breaking off more pieces until there’s nothing left to do.

When you’re writing a skeleton and you come to a medium-sized piece of logic like “figure out whether someone has won the game”, don’t spend too much time worrying about how to flesh it out. A task like this is a perfectly sized “milestone” that we can work on properly later. For now, write a placeholder function to come back to (in this case, something like get_winner). Think briefly about the interface of this function - the arguments it will need, and the data it will return.

A code skeleton for Tic-Tac-Toe

Let’s try sketching out a skeleton for our Tic-Tac-Toe engine. Before reading any further, spend a few minutes sketching one on your own. If you’re having trouble, start by making a list of as many of the individual challenges involved in making a Tic-Tac-Toe game as you can. Don’t worry about arranging them or putting them in an order. You could also try temporarily forgetting about code completely, and draw a flow chart that describes the rules for playing Tic-Tac-Toe.

Here’s the skeleton that I came up with:

board = new_board()

# Loop through turns until the game is over

loop forever:

# TODO: hmm I'm not sure how best to do this

# right now. No problem, I'll come back later.

current_player = ???

# Print the current state of the board

render(board)

# Get the move that the current player is going

# to make.

move_co_ords = get_move()

# Make the move that we calculated above

make_move(board, move_co_ords, current_player)

# Work out if there's a winner

winner = get_winner(board)

# If there is a winner, crown them the champion

# and exit the loop.

if winner is not None:

print "WINNER IS %s!!" % winner

break

# If there is no winner and the board is full,

# exit the loop.

if is_board_full(board):

print "IT'S A DRAW!!"

break

# Repeat until the game is over

Looking over this skeleton, I notice that it is made up of about 6 main components:

new_boardrenderget_movemake_moveget_winneris_board_full

Now these are some well-sized chunks of work. We can work on each of them in almost total isolation, without having to worry about the others. When we’re calculating whether our game has a winner yet (get_winner), we can completely forget about how it is actually played (get_move, make_move). Once we’ve finished writing each of these components and have glued them all together, we’ll have finished our Tic-Tac-Toe engine. After all, if you take the right body parts, stitch them onto each other and apply electricity, you’ve got yourself a fully-functional Frankenstein’s monster.

Our initial task list is neither exhaustive nor binding. When writing a big program you will always encounter new problems that you didn’t anticipate. You will always change your mind about how to arrange several limbs of your skeleton, but adaptation becomes much easier when you have an actual plan that you can adapt. We will use the above task list as “milestones” - checkpoints that allow us to constantly verify that we are on the right track.

Run code frequently

We’re going to run our code very frequently; at an absolute minimum once every time we complete a milestone. This will make bugs easy to locate and destroy, because there will be very few places in which they can hide. If our program is broken, but was working 10 minutes ago, then I’ll bet you pesos to pizza that there’s a bug holed up in the couple of lines we wrote during those fateful 10 minutes.

We could instead write hundreds of lines of code in one go before finally running our program once and crossing our fingers. But whilst high-risk moments of truth make for a good movie, they make for terrible software. In a good development process, the hero (that’s you) tests their work frequently. They use a small-steps approach in order to uncover bugs quickly. They have a better understanding of the internals of their code because of this, and can frequently adjust and course-correct their plans. They might not produce a thrilling box office hit, but they will ensure that the software that powers the box office actually works.

Building a Tic-Tac-Toe engine

We’re now ready to grind down our first, appropriately-sized milestone - making the Tic-Tac-Toe board.

Remember that if you ever need a hint, I’ve written an example program that you can take inspiration from.

1. Representing the board

We’re going to start by making a “data structure” that stores the state of the game board. Tic-Tac-Toe is played on a 3x3 grid, and in code, grids are often represented using nested lists, or “lists of lists”. If you haven’t come across this idea before, read the explanation of lists of lists in part 1 of my Game of Life project.

[

['X', None, 'O'],

['O', None, None],

[None, 'X', 'X']

]

Each element in our list-of-lists will represent a square on the board. In each sqaure we will need to be able to represent the 3 possible states - O, X and empty. I suggest representing O and X using the characters O and X, and an empty square using None or nil or however it is that your programming language represents “nothing”.

Your first task is to write a new_board function that takes in 0 arguments and returns an empty, 3x3 grid. Test that your function works with a simple print-statement.

print new_board()

=> [[None, None, None], [None, None, None], [None, None, None]]

2. Print the board

Basic print-statements are fine for debugging, but our players deserve something more refined. In this milestone we’re going to write a function whose only job is to pretty-print our board to the terminal in a form that is useful to humans.

Write a render function that takes in 1 argument - a Tic-Tac-Toe board - and prints it to the terminal. This function does not need to return anything. You can format the board however you like; I personally found it useful to add co-ordinate markers around the edge to make it easier for human players to reference specific squares.

Test your render function by using it to print some dummy boards. Construct these boards by generating an empty board using new_board and adding moves to it manually.

board = new_board()

board[0][1] = ‘X'

board[1][1] = ‘O'

render(board)

=>

0 1 2

------

0| |

1|X O |

2| |

------

We’re going to delete this test code almost immediately, but that’s fine, code is free. Writing throwaway scripts like this isn’t cheating - it’s just good practice.

3. Get player input

Now that we’ve got a board and a way to display it, we’re ready to start playing.

In this milestone we’re going to work out how to ask our human players to input their moves. Because we understand the extreme power of focussing on one thing at a time, we’re not yet going to worry about using these moves to update the board. Once again, this temporary shortcut is not cheating.

We could ask our players to input their moves in many different formats. I like asking for X and Y co-ordinates, because this maps well onto our grid data structure. But you could also assign each square a number from 1 to 9, or a word, or a letter.

1 O 3

4 X 6

O 8 9

The decision of how to ask our users for input is very low-stakes, and it doesn’t matter much if we change our minds later. This is not because user interfaces aren’t important - they are a vital part of a useful, functional program. Rather, the decision of how to ask our users for input is very low stakes because it is so easy for us to change, even if we’ve already finished the rest of our program. If we do change our minds then we should only have to update the section of our code that asks our players for input. The other components of our program should not have to care about this change. Once we have turned a player’s input into a move co-ordinate, the code that uses this co-ordinate to update the board shouldn’t have to know or concern itself with where the co-ordinate came from. This is a concept known as modularity - more on which in future projects.

You should still strive to make the best decisions you can. But you should also make sure to understand when a decision is binding, when a decision is easily reversible, and how you can restructure your code so that a decision becomes easily reversible. Think about the extent to which other parts of your program rely and care about your decisions. Would it be awkward for them if you changed your mind later? For example, it’s far more important that we cast-iron decide on our tic-tac-toe board’s shape than on its size. Changing our board from square to hexagonal would have far more knock-on effects than changing its height from 3 squares to 4.

Write a get_move function that takes 0 arguments, and returns the co-ordinates of the player’s chosen move as a 2-element tuple or array (one element each for the x and y co-ordinates), or whatever works best in your language.

Test it by running it and printing its output:

move_coords = get_move()

=> What is your move's X co-ordinate?: 1

=> What is your move's Y co-ordinate?: 2

print move_coords

=> (1, 2)

4. Execute moves

Now that our players can input their moves, it’s time for us to use those moves to update the board. We’re still not going to worry about whether either of our players has won. You can probably guess why.

In this milestone you’re going to write a function called make_move. As the name suggests, this function will execute a Tic-Tac-Toe move by updating the board. make_move will not print the board; printing is the job of our render function from part 2. Instead, we’ll use make_move to update the board, then separately pass the updated board into render for printing.

Before going any further, think about what arguments make_move will need to take in in order to update the board.

The answer is that make_move will need 3 arguments:

- The board

- The co-ordinates of the move

- The player who is making the move (so that

make_moveknows whether to insert anOor anXinto the board)

Return values and mutation

We have a choice about what our make_move function returns. It could either:

- Return a new board with the given move added:

new_board = make_move(old_board, (1, 1), 'X')

# `old_board` still represents the old position

# `new_board` is equivalent to `old_board` PLUS an 'X' at (1,1)

- Or return nothing, and update (or mutate) the board that it was given:

make_move(board, (1, 1), 'X')

# `board` has been mutated directly to add an 'X' at (1,1)

You should usually be wary of mutating a function’s arguments. Mutation can be surprising and unexpected, and can make for subtle, hard-to-diagnose bugs. It’s often much clearer to leave a function’s arguments unchanged, and to instead return new data representing a new state.

Mutation can sometimes be a defensible design choice. However, having seen the future, I know that this project will be easier if we steer clear of it. We should leave the board that make_move is given untouched, and return a brand new one instead.

When I was writing the first version of my code for this project, I wrote make_move using mutation. It took me a while to discover the problems with this decision, but, thanks to modularity, once I did I was able to come back and change my design with very little invasive surgery.

If the idea of mutation doesn’t make sense yet, don’t worry. It’s a subtle concept, and a thorough understanding of it is not necessary for this project.

You’re now ready to write a make_move function that takes in 3 arguments - the board, the move co-ordinates, and the player making the move. It should not mutate the board that it is given, and should return a new board, with the new move made.

Test your work by making some moves.

board = new_board()

move_coords_1 = (2, 0)

board = make_move(board, move_coords_1, "X")

render(board)

move_coords_2 = (1, 1)

board = make_move(board, move_coords_2, "O")

render(board)

Error handling - an edge-case

How does your make_move function deal with the following situation? How should it deal with it?

board = new_board()

move_coords = (2, 0)

board = make_move(board, move_coords, "X")

board = make_move(board, move_coords, "O")

=> ???

I think that the best thing to do when make_move is given an illegal move is for it to panic and raise an exception. I want make_move to be responsible only for executing moves, and absolutely nothing else. This means that its “contract” with the rest of the program is that the moves it is given had better all be legal, or else it’s going to have a freak out.

If we decide that we want to allow a player who makes an illegal move to retry with a different choice, then I would want us to make a separate function whose job it is to validate moves (maybe called is_valid_move). This might look something like:

move_coords = None

while True:

move_coords = get_move()

if is_valid_move(board, move_coords):

break

else:

print "Invalid move, try again"

board = make_move(board, move_coords, player)

make_move still freaks out if we give it bad input, but we’ve added some extra code to ensure that we don’t.

Update your make_move function to raise an exception if it’s given an illegal move. Make sure that it works.

board = new_board()

move_coords = (2, 0)

board = make_move(board, move_coords, "X")

board = make_move(board, move_coords, "X")

=> Exception: "Can't make move (2, 0), square already taken!"

5. Combining our work so far

So far we have written several functions that together can:

- Make a new board

- Print a board

- Ask a human player for a move

- Update a board with a move

Let’s join these components up to make a prototype program that allows the O and X players to take alternate moves until the board fills up. When the board fills up the program will probably crash. This is fine.

This is not the dummy’s approach to software development. I’m not blowing smoke at you - “you’re only an advanced beginner, it’s OK if your programs crash sometimes and don’t do everything that they’re meant to.” My own version of Tic-Tac-Toe started life as an incomplete program that broke a lot. Then I kept working on it, adding one feature and a few lines at a time, until it had stopped breaking and was complete.

Start by looking back at our code skeleton from the introduction. Pick out the bits that you need, and plug in our actual-code-so-far. You’ll notice that we haven’t yet written any code that will alternate moves between O and X - see if you can write this yourself. There are several reasonable ways to do it, and my example code is there if you need it.

Once you’ve got your sort-of-Tic-Tac-Toe program working, you’re ready to move on.

6. Check for winners

Hope and dreams and games of Tic-Tac-Toe are won or lost by one player getting 3 Os or Xs in a straight line. It’s our job to identify victories and declare champions. Stop and think for a minute or two about how to teach a computer to work out whether either player has won a game of Tic-Tac-Toe.

When I was thinking about this, I asked myself “how does a human work out whether either player has won a game of Tic Tac Toe?” Asking “how would a human do this?” can be a very useful way to design programs. Often (not always), a computer will do things in the same way as a human would, only much, much faster. In this case, the answer I came up with was “a human would look at every possible line of 3 grid squares, and check whether any of them contain all Os or all Xs.”

Write a get_winner function that takes take 1 argument - a board - and returns the ID of the player that has won (O or X), or None if no one has won yet. I’d suggest that you structure your function like this:

- Build a list of all the lines on the board - columns, rows and diagonals (eg. -

[[O, X, None], [X, O, X], # etc...) - For each line in this list, check whether it contains all Os or all Xs. If yes, return the character of the winning player (

OorX). If no, continue onto the next line - If none of the lines on the board are winners, return

Noneornilto indicate that no one has won yet

Test your function with some practice boards:

board_1 = [

['X', 'X', 'O'],

['O', 'X', None]

['O', 'O', 'X']

]

get_winner(board_1)

=> 'X'

board_2 = [

['X', 'X', 'O'],

['O', None, 'X']

['O', 'O', 'X']

]

get_winner(board_2)

=> None

Bonus points are available for writing “unit tests” like in section 3 of my Game of Life project. These tests will help ensure that you have covered every possible edge-case, and that don’t accidentally break your code in the future.

Once you are confident that your get_winner function works, plug it into the rest of your program. Your program should still allow players to alternate taking turns, but now it should also end the game when one player makes a line of 3.

Then there’s only one thing left to do.

7. Check for a draw

Not all games of Tic-Tac-Toe end in a victory. If both players are evenly matched then a game may end in a hard-fought draw. Figure out how to add this logic to your program.

Since this is the final piece of this project, that’s all the advice I’ll give you. Walk yourself through the problem step-by-step. Check my example code if you get stuck.

8. Keep testing

Keep testing your Tic-Tac-Toe engine by playing practice games against yourself and your friends. Fix bugs (there will be bugs), until no bugs remain.

9. Final task - say hi!

You now have a fully-working, bug-free Tic-Tac-Toe engine. Congratulations! After pausing to pat yourself on the back, send me an email to let me know that you’ve finished! I’d love to hear from you. Have a go at my other programming projects for advanced beginners as well - ASCII art and Game of Life. Most importantly, sign up for my mailing list (see the bottom of the page) to find out when the next part of this project is released and you can start work on your unbeatable Tic-Tac-Toe AI.

Once you’ve completed these final tasks, compose yourself and venture boldly into the extensions section below, or straight on to part 2.

Extensions

This section contains several extension projects that build on top of our Tic-Tac-Toe code so far. Pick and choose the ones that you like the look of, and dream up your own, entirely new ones. Because these are extension projects, I’ll be giving you far fewer tips and pointers. Instead, you should be your own guide and walk yourself through them using the techniques and strategies that we used to build our main Tic-Tac-Toe game. Start by breaking up the tasks into small pieces. Work on one piece at a time and run your code as often as you can. Don’t be afraid of writing test code that you quickly throw away, and don’t be afraid of writing programs that only do 50, 25, or even 1 percent of what you want them to eventually be capable of.

Before starting work on the extensions, save a copy of your code. We’re going to need it for the next section of the main project - “Making a perfect TicTacToe AI”. You can save a copy by either duplicating the file, or using “git” to check out a new branch. Both approaches are totally fine, and don’t feel bad if you haven’t come across git before.

Extension 1: Build an “AI” player that makes random moves

Add the option for a single human player to play against an AI computer player. This AI player should start by only making random (legal) moves. We’ll look at how to make them smarter in the next project. If you want to get a head start on making your AI player smarter then go wild.

Extension 2: Improve the user experience

Allow each player to enter their name. Print out random celebration lines when someone wins. Add color to the printouts. Use your imagination.

Extension 3: Play different games

There are lots of games that are like Tic Tac Toe, only better and more complex. Look up Connect 4, and use the techniques you learned in this project to write an engine for it it. Steal shamelessly from your code in this project.

Try changing the rules of Tic Tac Toe too. Make the board bigger, add a third player, make the board a weird shape.

Extension 4: Networked gaming

Allow your players to play on different computers, over a local network. Each computer should run its own copy of your program, and they should send their moves to each other via TCP.

Extension 5: Leagues, statistics and databases

Keep track of players and their results. Use a database to store match results, and add tools to print out league tables. Add a username and password login system so that players can’t impersonate each other - make sure to look up how to securely store passwords first (keywords - hashing and salting).

Running a networked Tic Tac Toe league may feel like taking things Tic Tac Toe too far. But networks and league tables are not specific to Tic Tac Toe. In a future project we’re going to build the game “Tron” (like from the movie). Tic Tac Toe is fun, but Tron is awesome. You’ll be able to reuse a lot of your networking and results-tracking code from your Tic Tac Toe in your Tron.

See you in part 2, where we’ll ruin the noble game of Tic Tac Toe by building an AI that plays it perfectly.