Programming Projects for Advanced Beginners #3b: Tic-Tac-Toe AI

09 Oct 2018

This is the second and final part of our quest to build an unbeatable, perfect Tic-Tac-Toe AI. In part 1 we wrote a Tic-Tac-Toe engine that allowed two human players to play against each other. In part 2, we’re going to use the minimax algorithm to build a flawless AI.

NEW

Subscribe to my new "Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners"

newsletter to receive concise weekly emails containing specific,

real-world ways to make your code cleaner and more professional.

Each week I review code sent to me by one of my readers. I highlight

the things that I like, discuss the

things that I think could be better, and offer suggestions for how

the author could make their code cleaner and easier to work with.

Subscribe now to receive these invaluable improvements in your inbox

every week, completely free.

First we’re going to warm up by writing some simpler AIs that choose their moves using if-statements and rules of thumb. As we do this we’ll build out the code that connects our computer players to our existing Tic-Tac-Toe engine. Once we’ve got our warmup AIs working and have written and verified this generic infrastructure we’ll be ready to give our total focus to our final goal: making a perfect Tic-Tac-Toe AI.

As with all my projects, I’m going to leave all of the difficult work to you and throw you right in at the deep-end. But I’ll also give you gentle reminders on how to swim, as well as some new tips on swimming best practices. If you do get completely stuck then I’ve written some example code. You can always use it to point yourself back in the right direction.

Today’s lesson - Interfaces

We’re going to write several different Tic-Tac-Toe AIs, each of which will choose their moves using different strategies of varying degrees of complexity. And we won’t be the only ones doing this. We also want to be able to challenge your friends and family to a duel - your best AI against theirs. We want them to be able to build their AIs on their own, and to be able to easily plug them into our Tic-Tac-Toe engine so that we can have a rumble. Then we want to crush their AIs and their spirits. And we will. Mark my words. We will crush them.

This raises an important question. We’re going to be writing many different AIs. Your enemies are going to be writing AIs of their own too. How can we ensure that all of these algorithms are able to talk to each other? How can we ensure they they can all plug into our Tic-Tac-Toe engine, even though they were all developed independently and take completely different approaches to choosing their moves?

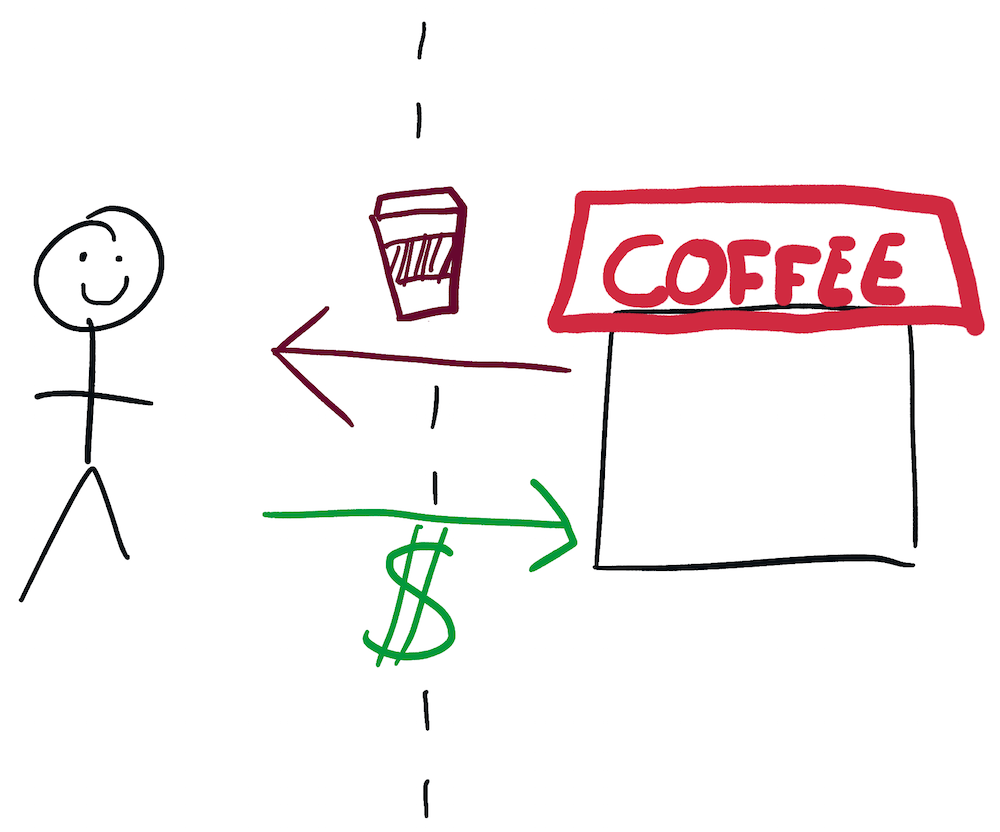

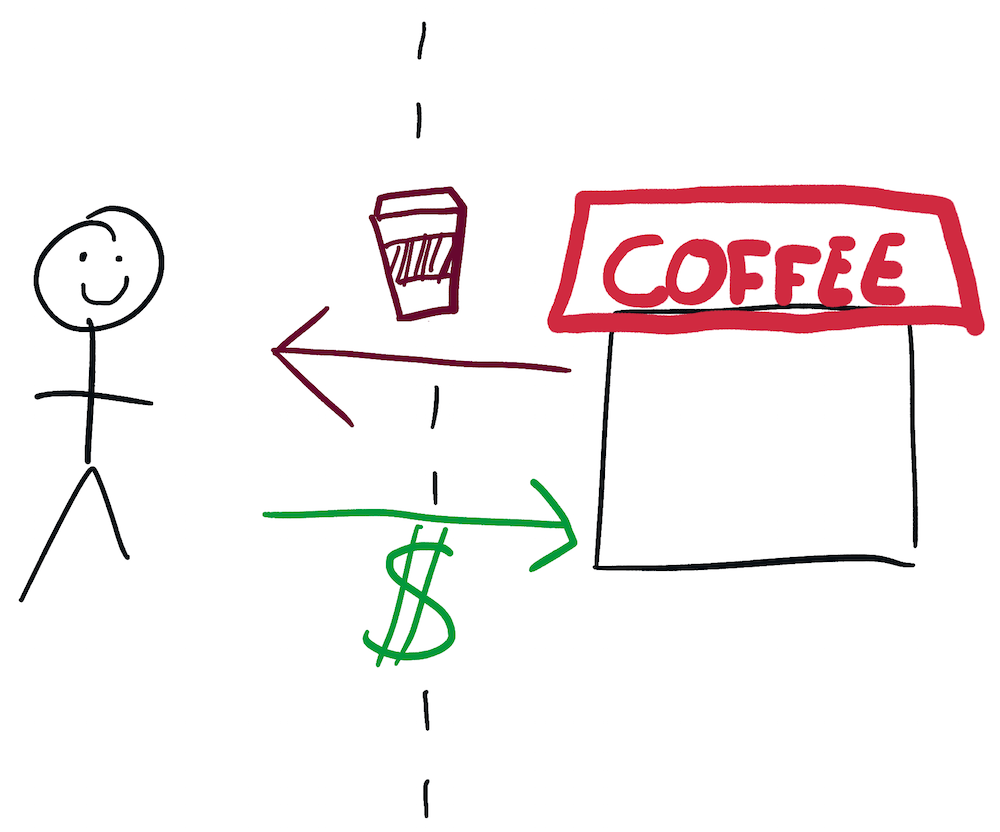

We will solve this problem and make sure that all of our code is compatible by using interfaces. An interface is a definition of the way in which different components of a system communicate with each other. For example, the interface between you and a coffee shop is that if you give the coffee shop the right amount of money, they will give you a coffee.

The interface between you and the dry cleaners is that if give the dry cleaners some clothes, they will give you a ticket. And if you wait a few days and then give them a ticket and the right amount of money, they will give you back your clothes minus any foul stenches they may have had.

Interfaces are powerful because the component on one side of an interface boundary doesn’t need to know any details about how the component on the other side works. Another real-life example: the interface between your headphones and your laptop is that if you plug a 1mm jack into your laptop, your laptop will send that jack electrical signals in a pre-agreed format that can be converted into sound. But your laptop doesn’t actually care what your headphones do with these signals after they’ve crossed the interface boundary, and your headphones don’t care how the signals were originally generated. They could have come from YouTube, Spotify, Skype or Minecraft. As long as the laptop and headphones conform to the agreed interface, they can generate their inputs and outputs in any way that they please.

Similarly, you don’t have to care how the coffee shop produced the coffee it gave you (so long as everyone involved washed their hands and was compensated according to your ethical standards), and the coffee shop doesn’t have to care where your money came from. You could have taken it out of an ATM (your interface with your bank), found it on the street, or received it from the US Federal Reserve in exchange for toxic mortgage-backed securities as part of the 2008 TARP bailout. The implementation of an interface - how a component lives up to its end of the deal - is completely separate from what the deal actually is.

Poorly-designed interfaces are messy and hard to understand. Take the IRS. If you fill out a trillion forms, do some maths, write a check, post it to the government, and phone them up a few days later to make sure that they got it, then the IRS will mark your taxes as paid. This interface is difficult and stressful, and products like TurboTax exist to provide a better one. If you upload some documents, click some buttons, abdicate some responsibility, and pay TurboTax $100, then they’ll figure out the rest. TurboTax does also lobby the Federal government to make sure that your direct interface with the IRS is as bad as possible in order to keep you paying them that $100 every year, but this doesn’t diminish their utility as a teaching example. Once you’ve clicked “Submit” you don’t care how they get your tax return to the IRS, so long as they do. They could have an army of Mechanical Turks, a very messy but unfailingly accurate PHP program, or infinite monkeys with infinite CPA qualifications.

Interfaces in code

Interfaces are everywhere in code too. Every function is an interface - “you give me X and Y and I’ll return you Z”. It’s very possible and very useful for multiple functions to share the same interface.

For example, imagine that you’re building a system that makes personalized movie recommendations. You want your system to be diverse and imaginative, and so you want it to have several different methods of generating recommendations.

You would be well-advised to construct your system out of functions that each use different techniques to recommend movies, but all conform to the same interface. This interface could be something like “you give me the list of movies that a user liked, and I’ll return the 3 movies that I think they should watch next.” One function could look for movies with similar names to those that the user liked. Another could be looking for movies that were liked by other users with similar tastes. And a final one could always return ["Con Air", "Con Air", "Con Air"], because there is no better movie than “Con Air”. Even though all of these functions do extremely different things behind the scenes, they all conform to the same interface. And because they all conform to the same interface, new recommendation algorithms can be dropped in and swapped out, with no new custom code required to plug them in.

# By using "first-class functions", we

# can just add our new recommender functions

# to this list

recommender_functions = [

similar_names,

similar_tastes,

con_air

]

for f in recommender_functions:

print f(user_favorite_movies)

# => ["American Beauty", "American Beauty 2", "Quest for Beauty"]

# => ["Aladdin", "Frozen", "Wall-E"]

# => ["Con Air", "Con Air", "Con Air"]

We are going to specify our own interface that defines how our Tic-Tac-Toe engine and our Tic-Tac-Toe AIs communicate with each other. Right now our engine has sections of code that take care of printing the board, checking for wins, checking for draws, alternating sides, checking for legal moves, and getting moves from the human players. We will keep almost all of this code the same; the only change we will make is to swap out the section that gets moves from humans and replace it with an AI.

We’ll decree that an AI function should accept 2 arguments - a board and the ID of the side whose move it is (O or X). The function should return the co-ordinates of the square that the AI would like to play in. As long as a function conforms to this interface - “you give me a board and an ID and I’ll give you back a co-ordinate” - we can easily plug it into our engine, without our engine needing to know anything about how it works behind the scenes. The function can decide on its move in any way it likes, using anything from a neural network to a Twitter poll to a complex system of levers and pulleys. In this project we’ll write AI functions that calculate their moves using stacks of if-statements, human decisions, and the elegant and unbeatable minimax algorithm. However, these are all implementation details that our engine won’t have to know or care about.

Note that in some programming languages, like Java and Go, interface is a special language keyword with a specific meaning. We are using the word in a more general sense. In many other languages, like Python and Ruby, you don’t have to write any code that officially “declares” an interface. You just tell other programmers who want to add new components to your system how everything works and which interfaces they need to conform to. If they do then everything else will Just Work.

Why it’s good to think in interfaces

Thinking about your programs in terms of interfaces makes your code neater and easier to extend. It pushes you towards designing your system as a series of discrete components that are each responsible for a small number of things, and that only communicate with each other through well-defined, well-understood pathways. This means that changing one component is less likely to cause bugs with another. As long as the component you changed still conforms to all the same interfaces, it will still interact with the rest of your system in the same way. A good sign that your code is making good use of interfaces and components is that you can easily sketch its structure using boxes and arrows, and don’t need too many arrows.

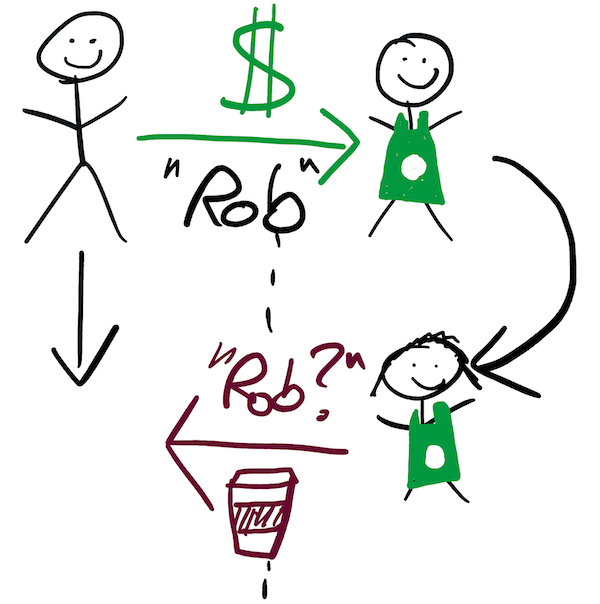

A world without well-defined interfaces is a world in which everything directly depends on the details of everything else. Complex or non-existent interfaces can sometimes be justified. In many Starbucks coffee shops you start as normal, by giving the barista money and an order in flawless Italian. But then, then instead of immediately receiving your coffee, you have to go and stand in the coffee bullpen until your name is called. This interface between you and Starbucks is more complex than the simple exchange of cash and caffeine that we discussed previously. It requires you, the user, to do more work, and to understand something about the internal workings of Starbucks. It does, however, increase the shop’s overall coffee throughput (measured in macchiatos per minute), which can only be good for busy bean lovers and holders of $SBUX stock.

You could argue that the increasing popularity of chain restaurants and coffee shops is indicative of people’s desire for consistent, well-defined interfaces with the world. They don’t want to have to care whether the yam harvest was good or bad this year or which days Julian is in the kitchen. They want to be served within 30 minutes and back out the door within 75. They want to pay by inserting their credit card into a standardized device and putting in a magic code. And they want to not have to worry about their family’s reputation in the community whilst they get drunk enough to forget about all the Jira tickets that await them the next morning. However, this is probably reading a little too much into decent, reasonably-priced pizza. A consistent interface doesn’t mean that everything is the same - it means that the way you interact with it is.

With a million metaphors under our belt, let’s build some Tic-Tac-Toe AIs that all conform to a consistent interface, and see for ourselves why interfaces are so helpful.

1. AI that makes random moves

We’re going to start by writing one of the simplest AIs possible. This AI will look at the board, find all the legal moves, and return one of them at random.

We’ll write a function called random_ai that conforms to our AI interface. This means that it accepts 2 arguments - a Tic-Tac-Toe board and the current player - and returns the co-ordinates of a move. You may notice that random_ai does not actually need to know the current player, since all it is doing is using the board to choose a random legal move. However, in order to conform to our Tic-Tac-Toe AI interface, it still needs to accept the current player as an argument. It can then simply ignore it.

Write random_ai now. Try it out on some test boards:

board = [

['X', 'O', None],

['O', 'O', None],

['X', None, None]

]

print random_ai(board, 'X')

print random_ai(board, 'X')

print random_ai(board, 'X')

print random_ai(board, 'X')

# => should print a random legal move each time

Make sure that it always returns a legal move.

Then plug random_ai into your Tic-Tac-Toe engine from the first part of this project. Your engine probably has a line that looks something like:

move = get_move()

get_move was the function that was responsible for getting the human player’s next move. Because of the delightfully modular way in which we constructed our Tic-Tac-Toe engine, you should be able to instantly swap in your new robot by changing this line to something like:

move = random_ai(board, current_player)

The rest of your program should continue to work as normal, with no further changes required. Run your program a few times and watch it play some random games against itself.

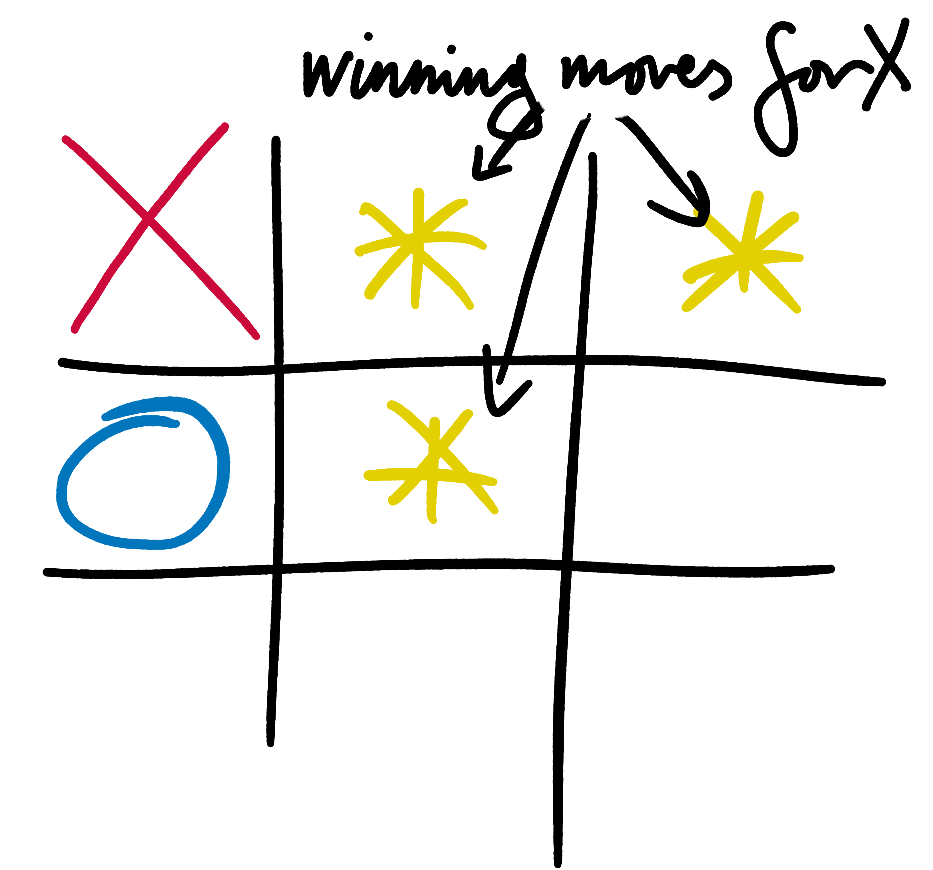

2. AI that makes winning moves

Let’s make a second, slightly more intelligent AI. Write a finds_winning_moves_ai function that returns a winning move if one exists, and a random move otherwise. It too should conform to our AI interface, meaning that it accepts 2 arguments - a Tic-Tac-Toe board and the current player - and returns the co-ordinates of a move. Unlike random_ai, finds_winning_moves_ai will need to use the current_player argument, because it needs to know whose winning moves it should be trying to find.

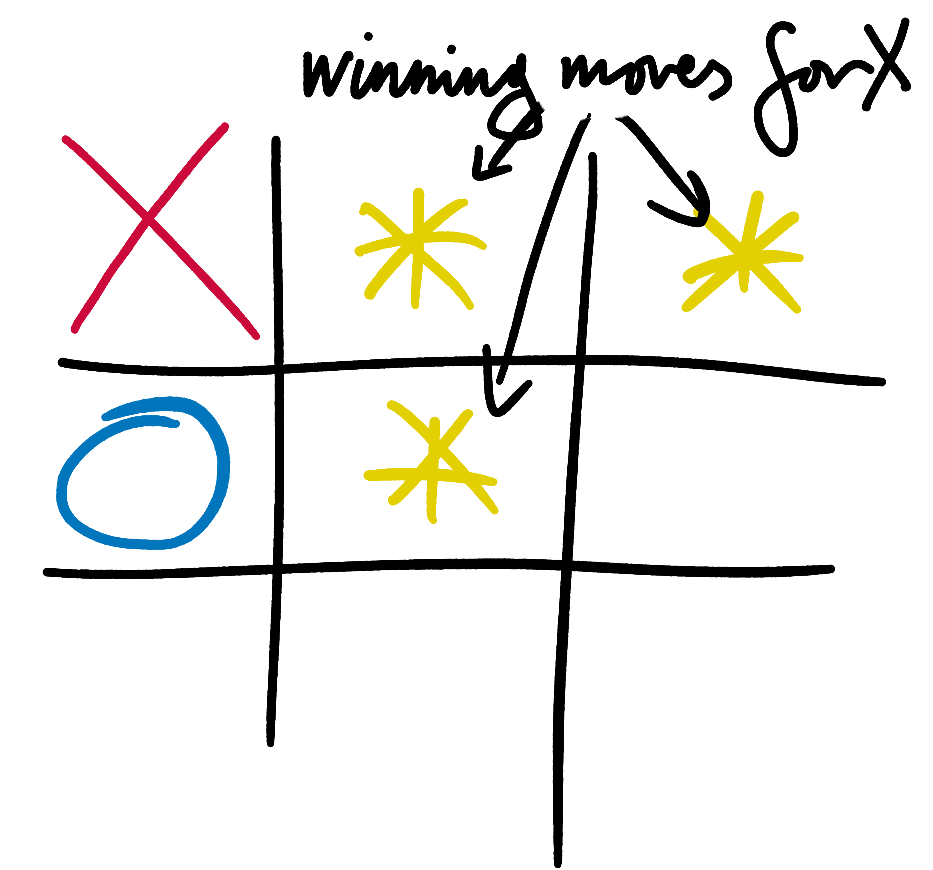

Once again, try out your finds_winning_moves_ai function manually on some test boards:

board = [

['X', 'O', None],

[None, 'O', None],

['X', None, None]

]

print finds_winning_moves_ai(board, 'X')

print finds_winning_moves_ai(board, 'X')

# => should always print (1, 0)

print finds_winning_moves_ai(board, 'O')

print finds_winning_moves_ai(board, 'O')

# => should always print (2, 1)

Then update your main program with your smarter AI. Because finds_winning_moves_ai conforms to the same interface as random_ai, this will be as straightforward as changing:

move = random_ai(board, current_player)

to:

move = finds_winning_moves_ai(board, current_player)

Powerful things, these interfaces. Run your smarter AI against itself a few times. How should the results of these games be different to those played by 2 random_ais? Should you see more or fewer draws?

3. AI that makes winning moves and blocks losing ones

This is the final approximate, or heuristic AI that we’ll write before starting work on our flawless minimax algorithm. Write a finds_winning_and_losing_moves_ai that conforms to our AI interface. finds_winning_and_losing_moves_ai should return, in order of preference: a move that wins, a move that block a loss, and a random move.

Test it out, plug it in. How should the results of these games be different to those between 2 finds_winning_moves_ais? Should you see more or fewer draws?

4. Refactoring the human

Now let’s bring back the human player. Remember, the point of an interface is that you don’t have to care how the thing behind the interface does its work. All of the functions that we’ve written so far are powered by highly sophisticated artificial intelligence, but it’s also completely permissible for us to define a function that conforms to the same interface but is powered by a real, fleshy human.

Write a human_player function that gets its move co-ordinates by asking for input on the command line, in the same way as you did in the first part of this project. The only difference is that this time human_player should conform to the AI function interface. Test it out, plug it in, play some games against yourself.

5. Different sides, different AIs

So far we’ve only been battling AIs against copies of themselves. But things start to get really interesting when you have different algorithms face off against each other.

First we’ll have to tell our program which algorithms should go in the arena. We could do this in the same way we’ve done it so far - directly changing the guts of the code - but this is not very satisfactory or user-friendly. Instead, we’ll give our AIs names - strings like "random_ai" and "find_winning_moves_ai". We’ll pass the (possibly different) names of the O and X AIs into our program (perhaps via the command-line), and use them to select the logic that should be used.

python tictactoe.py random_ai find_winning_moves_ai

We can convert these names into algorithms in several different ways. The approach that we will start with is to use if-statements in your main game loop:

# In your main game loop:

if player_name == 'random_ai:

move = random_ai(board, current_player)

else if player_name == 'find_winning_moves_ai':

move = find_winning_moves_ai(board, current_player)

# ... etc

This approach is a little verbose and cumbersome, but it works and is completely adequate. If you’re curious then use Google to find out how to select AIs with slightly more style using first-class functions and classes.

We’ll also have to update our main program to alternate between the different algorithms that are battling against each other as we alternate between taking turns for X and O. Do this now.

Once you’ve written this code, fight a random_ai against a finds_winning_and_losing_moves_ai a few times. The more intelligent AI should have a significant advantage.

5b. Repeated battles

Add a way to fight 2 AIs against each other thousands of times to find the average win percentages. I’d suggest structuring this like:

def play(player1_name, player2_name):

# Returns:

# * 0 if the game is drawn

# * 1 if player 1 wins

# * 2 if player 2 wins

def repeated_battle(player1_name, player2_name)

# Repeatedly call the `play` function and tally the results

This is just an experiment to see how much effect different rules and optimizations have on an AI’s skill-level. It’s not essential, and you can skip it if you want to move straight onto the final milestone: building a perfect AI.

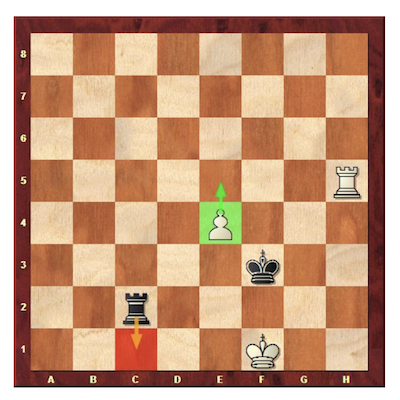

6. Building a perfect AI

I used to play in a lot of chess tournaments. They were played in vast, hushed halls, with no sound other than the gentle clacks of knights moving to F3. If you wanted to post-mortem your game after you had finished, there was usually a small analysis room off to the side. Here triumphant victors and grumpy losers pored over the past, trying to show how smart they had been or work out what they could have done better. The air was saturated with a gentle hubbub of “if I go there, she goes there; but if she goes there, I go there!” Players were looking at all the possible moves that they could have made in a position, and for each move trying to find their opponent’s best response. For each best response they tried to find the best counter-response, and so on and so forth until the game had ended or the result was no longer in doubt.

Assuming that your opponent will play optimally and trying to find the best responses to their best responses is pretty much what the minimax algorithm does. The only difference is that we’re going to use computers to do it perfectly and much, much faster.

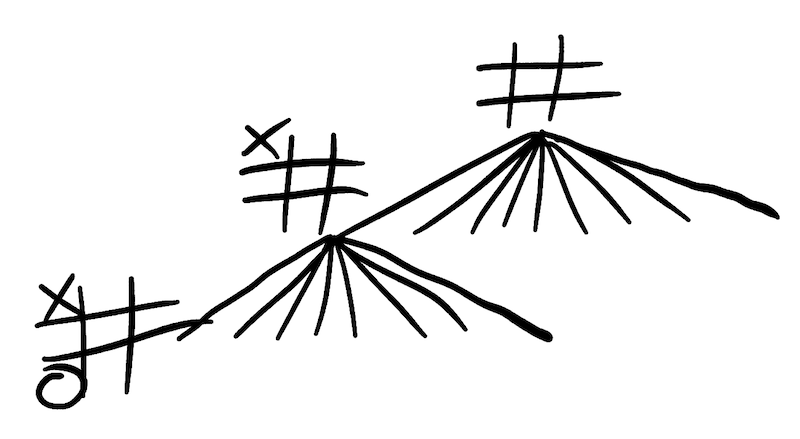

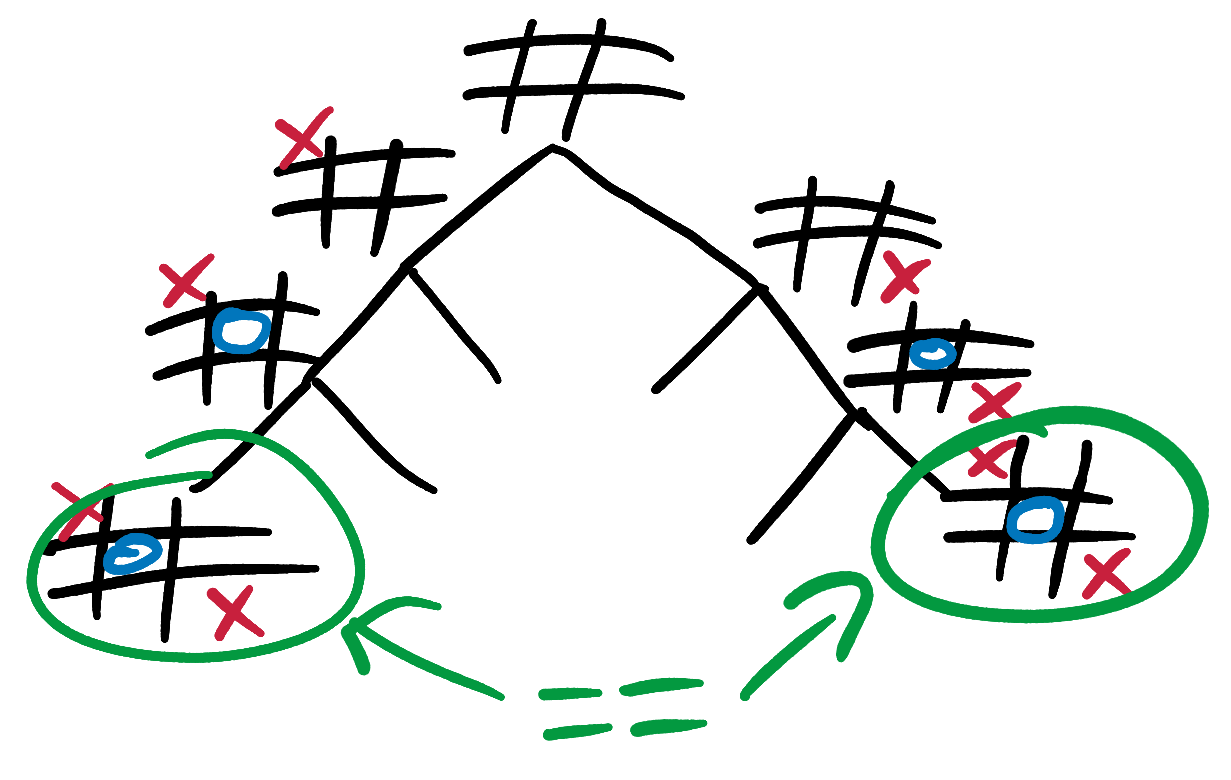

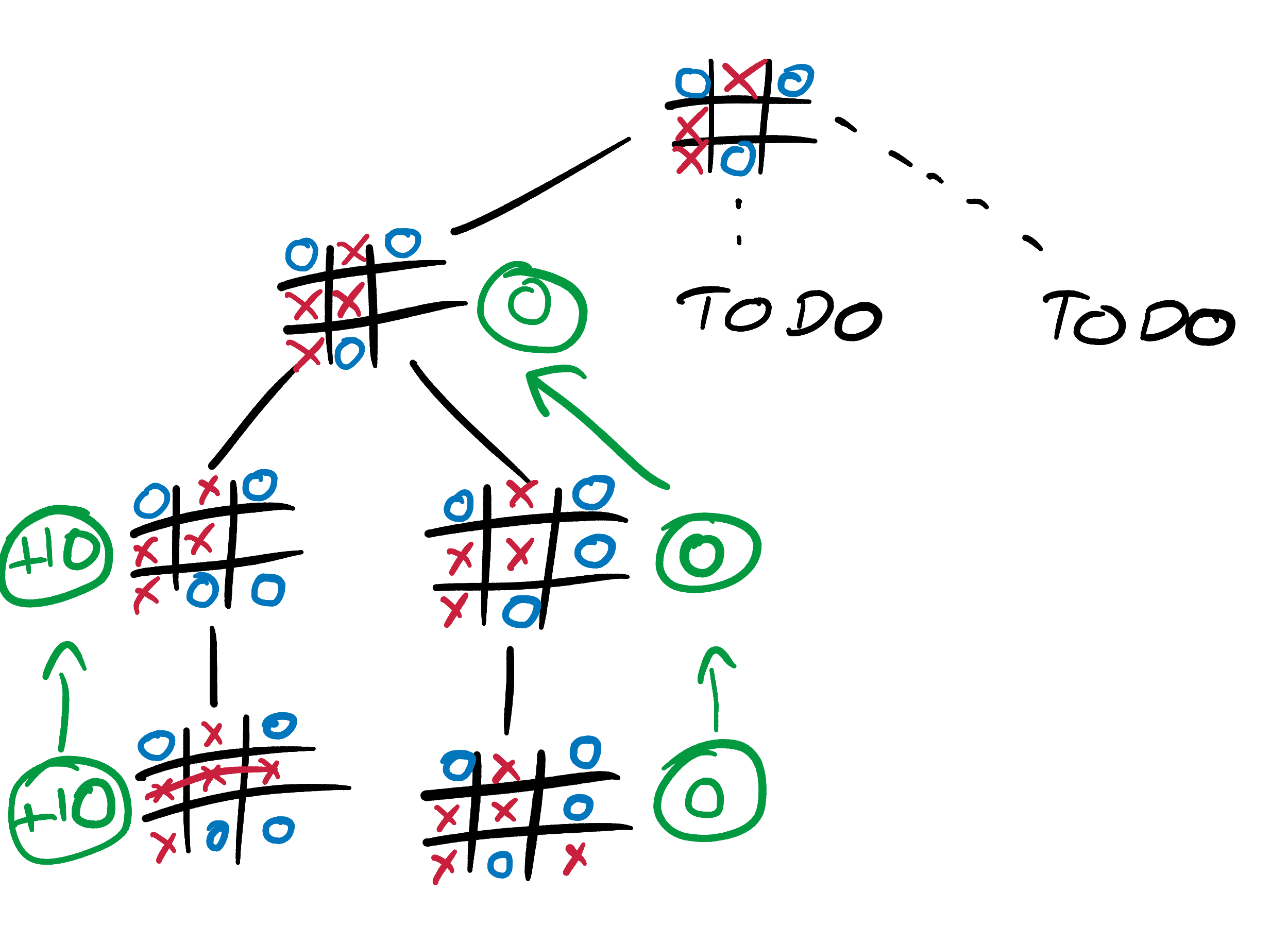

To begin the minimax algorithm, our AI will build a tree of all 250,000 possible games of Tic-Tac-Toe.

On its own, this tree won’t tell our AI anything useful. It will describe all the games of Tic-Tac-Toe that could ever be played, but it won’t say anything about how to use this information to make flawless moves. Possession of mountains of raw facts is not the same as knowledge of what to do with them. Only with the help of the minimax algorithm can our AI convert this Tic-Tac-Toe tree from dumb data into profound sylvan wisdom.

Minimax or maximin?

As Sun-Tzu once said (or was it my dad?), in order to be a good Tic-Tac-Toe player, you must see the battlefield through the eyes of your opponent. We will take to heart the wisdom of the ancients, and will train our AI in the ways of the most ruthless warrior the world has ever seen (or was it Sun-Tzu?).

In order to choose its moves, our AI will put itself in the mind of its opponent. It will see that it’s no good playing moves that will win if your opponent plays foolishly, but lose if they play well. You must assume the worst. You must assume that your opponent will choose the moves that maximize their own outcome, and you must choose the moves that MINimize these MAXimum outcomes for your opponent (hence: minimax). Leave them with no good choices, and assume that they will try to do the same to you.

If you prefer to think positively then you can also see this as MAXimizing your own MINimum outcome (maximin). Maximin and minimax are the same side of the same coin, seen from opposing perspectives.

Our AI will start by considering all of the current position’s legal moves, and assigning the position resulting from each move a numerical score. It will calculate these scores by working out what the result of the game would be if it were played out between two equally perfect players. Finally, it will choose the move that gives it the maximum score. This sounds straightforward enough, except for one tiny detail.

How exactly does it calculate those scores?

Scores

Our AI will need to be able to assign scores to 2 types of positions: those in which the game has finished (which we will refer to as terminal states), and those in which it has not. Terminal states are much simpler than non-terminal ones, so let’s start with them.

Scoring terminal states

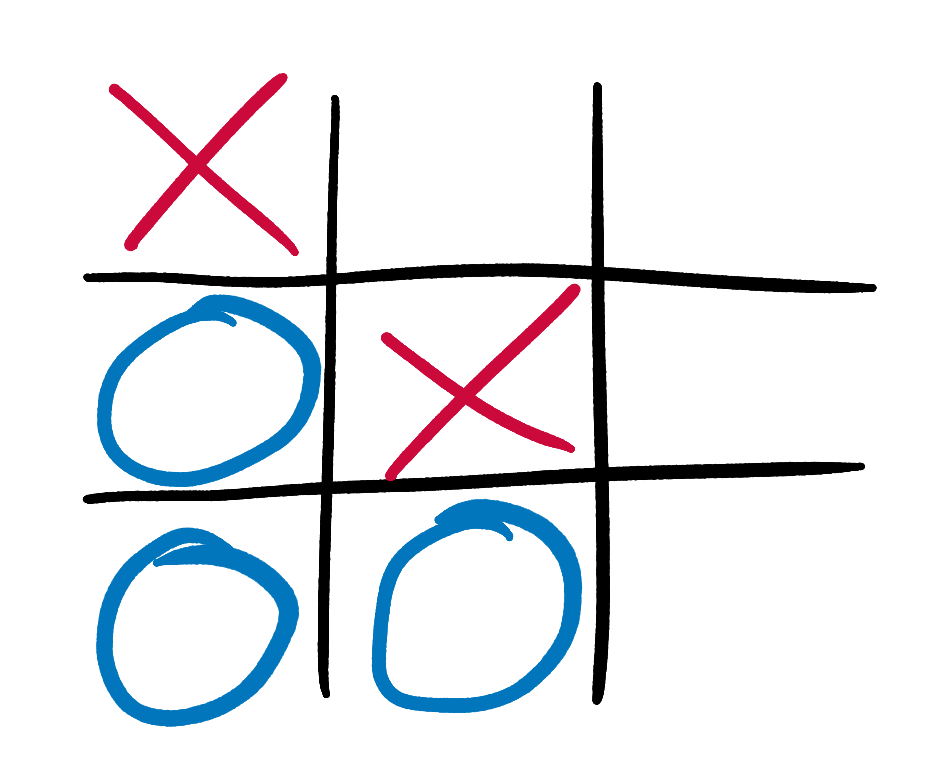

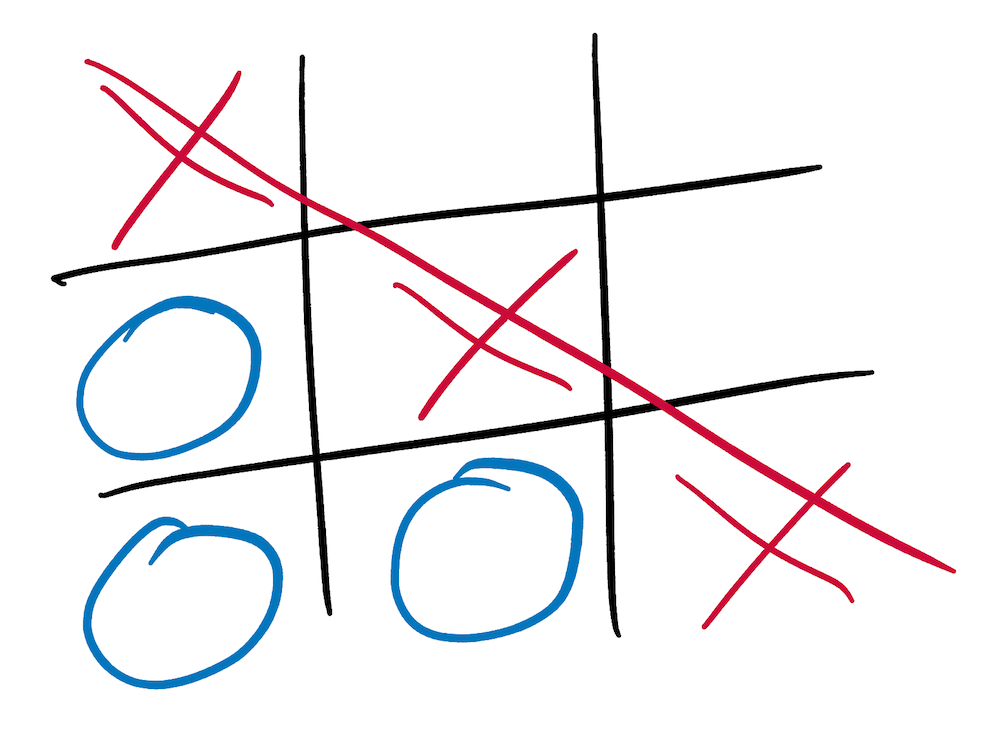

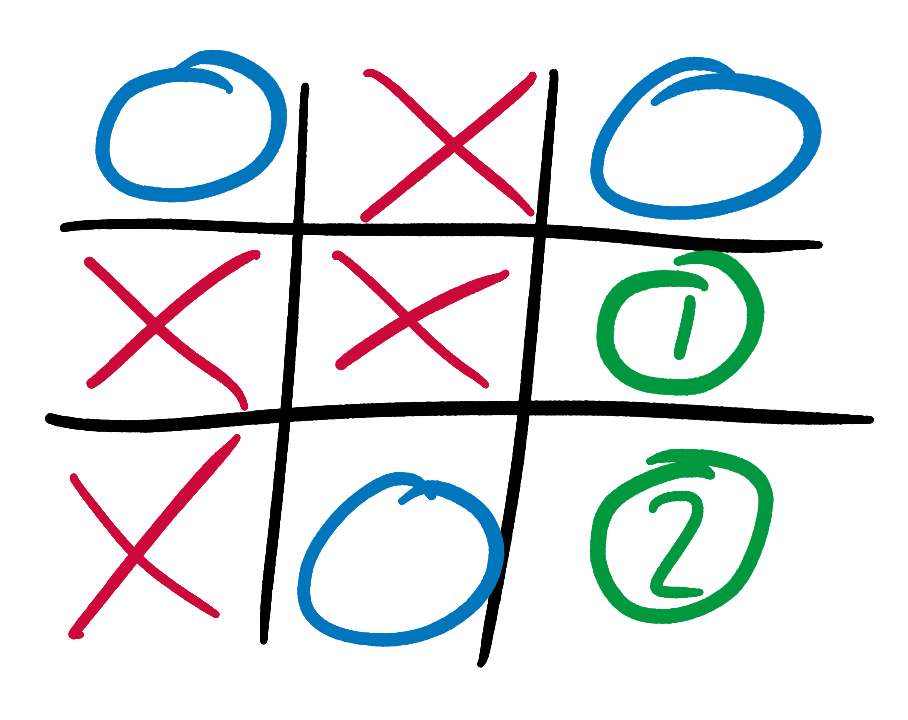

If a terminal state is a win for our AI, it gets a score of +10. If it’s a loss for our AI, it gets a score of -10. If it’s a draw, it gets a 0. That’s all there is to this rule. It applies only to completely terminal, game-over state. It does not apply to states in which the result is certain but has not yet been played out. For example, we can use the rule to immediately assign the following state a score of +10, since our AI (playing as X) has already won:

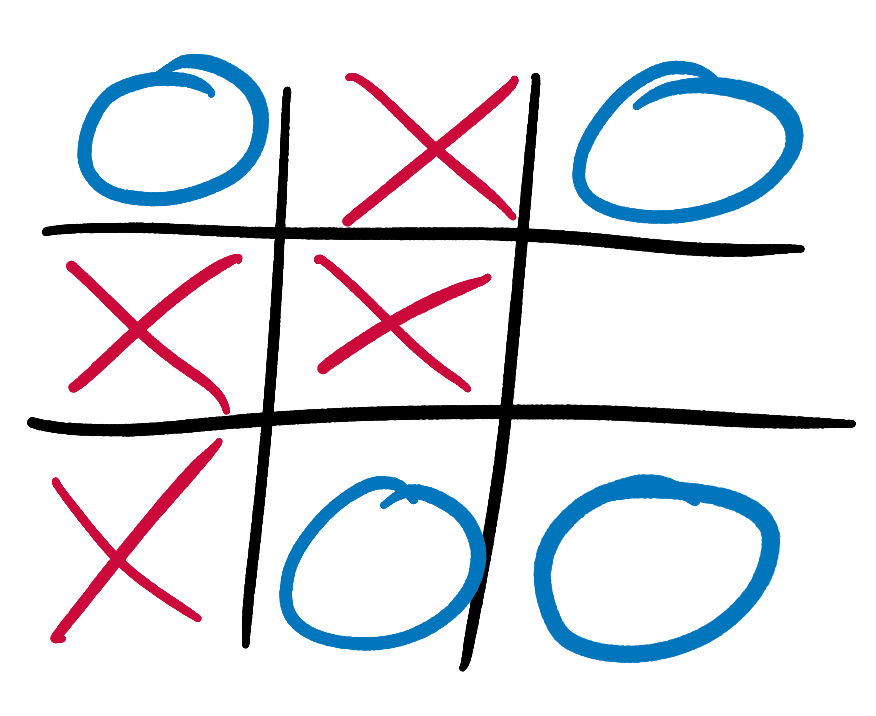

But we could not use it for the following state:

It’s clear to us savvy humans that our AI (still playing as X) is about to win. But it has not yet delivered the coup de grace, and the game is not yet officially over. We therefore can’t apply our terminal state rule, because we aren’t in a terminal state. We could score this state using another big ol’ pile of branching if-statements to work out if there is a winning move available, like we did in the previous iterations of our AI. But this won’t help us with more ambiguous states in which the eventual outcome is less clear.

We need a general rule that can score all non-terminal states, not just those in which the future result is obvious. We’re about to get a bit abstract, so pack a lunch and tell a friend to alert the police if you’re not back by 5.

Scoring non-terminal states

Our AI will score non-terminal states by working out what the outcome would be if both players finished the game by playing perfect Tic-Tac-Toe, and assign the state a score corresponding to that outcome. Sounds sensible enough. But this brings us right back to the very question that we are trying to solve - how exactly does one play perfect Tic-Tac-Toe? Don’t worry, we’re getting closer.

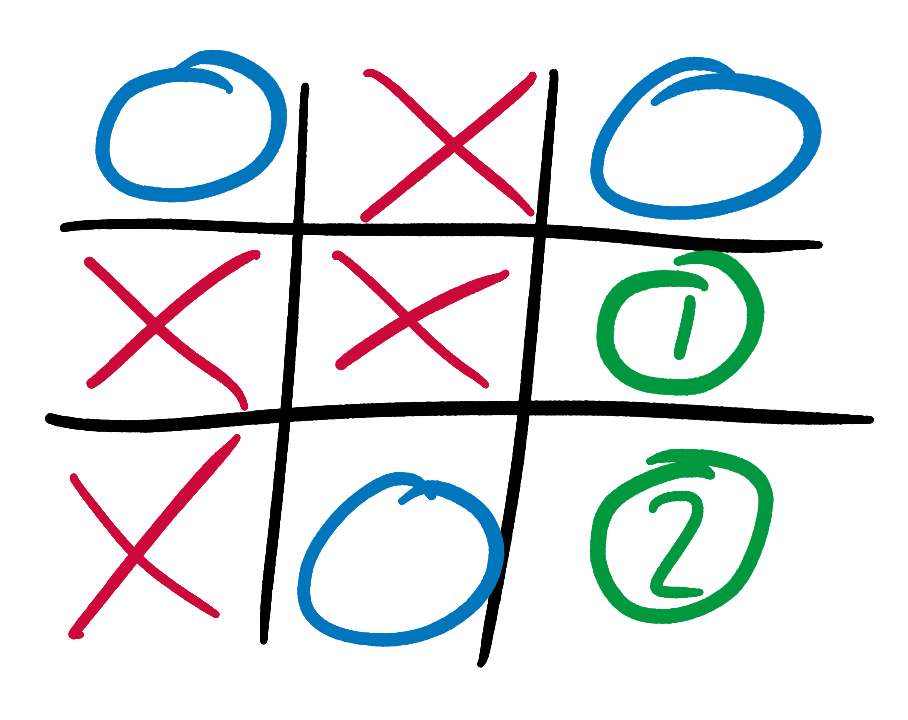

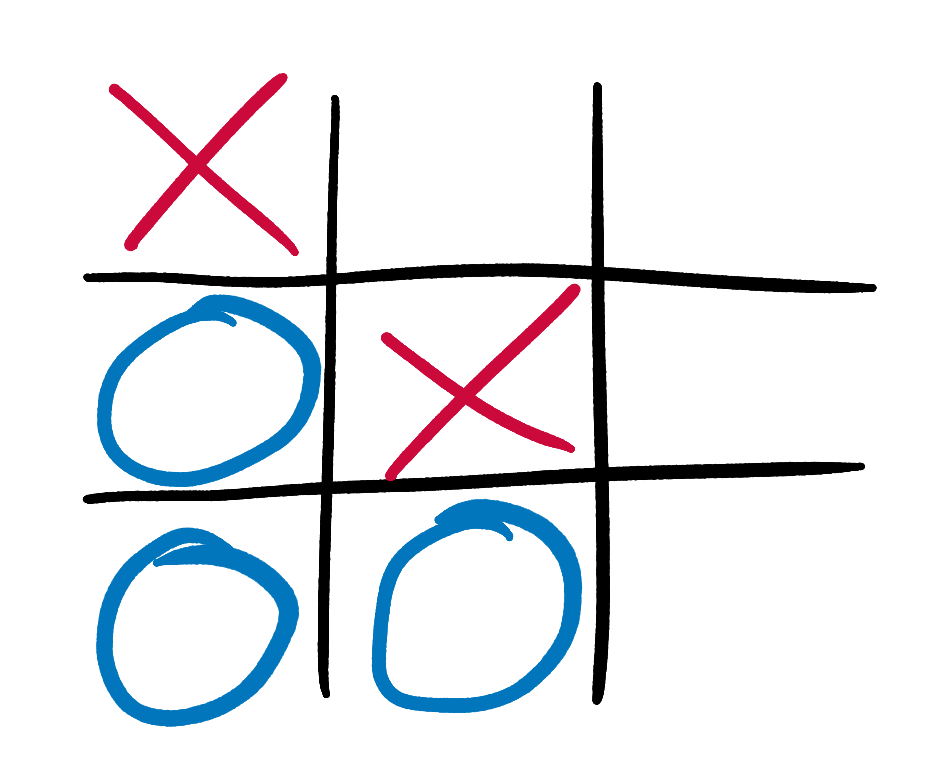

Minimax requires our AI to walk along the branches of its Tic-Tac-Toe tree, propagating concrete scores from the terminal states on the leaves up to more uncertain-looking early-game states. Let’s try some examples. It’s X’s turn to play. What score should our AI, playing as X, give this state?

The game is not yet over, so we can’t use our simple rule for game-over states from above. But X has only one possible move, and it results in a glorious victory. We can therefore say that with perfect play from both sides X will win. This is a slightly odd statement, since X has only one possible move and so has no choice but to play perfectly. But it’s still true, and it means that our AI should give this state a score of +10, even though it is not terminal. Our AI now knows that if it can reach this state then the game is as good as won, and should be just as excited about reaching this state as one in which it already has 3 Xs in a row.

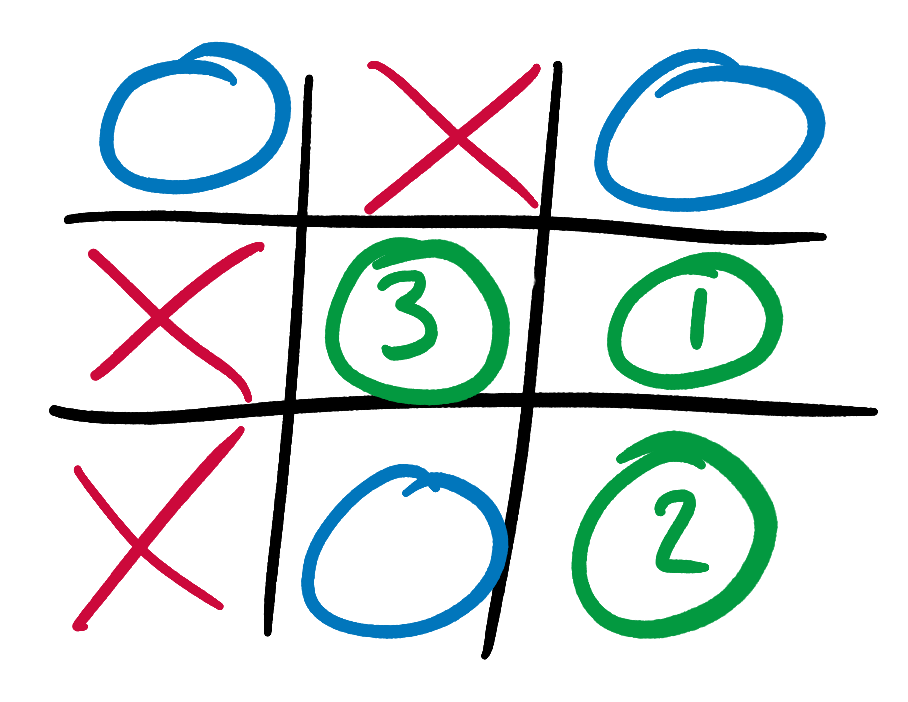

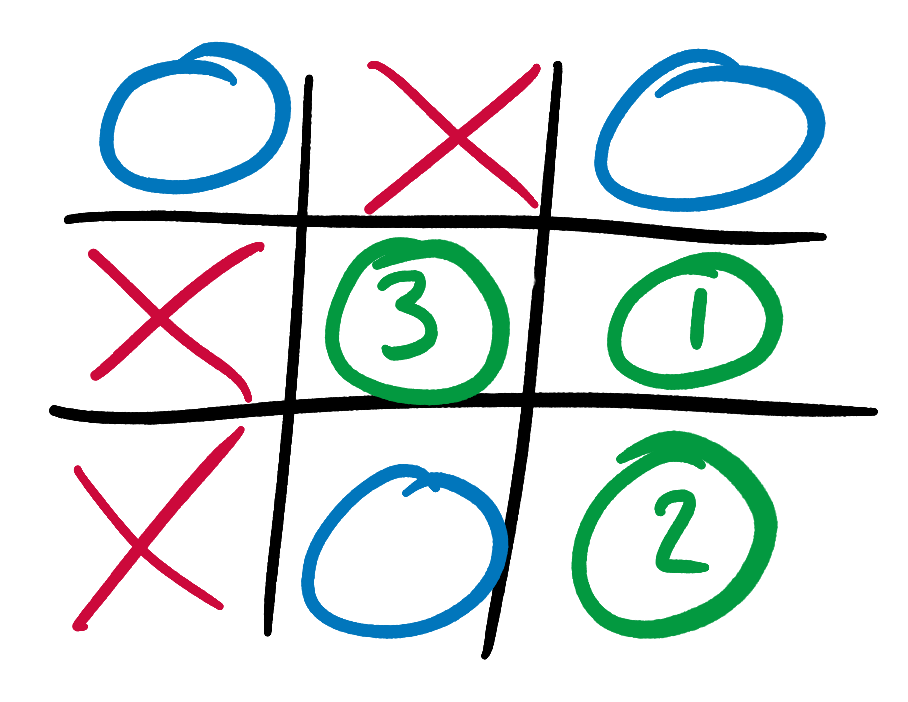

Let’s rewind the game by one move and climb one branch up the Tic-Tac-Toe tree. This time it’s O’s turn. What score should our AI, still playing as X, give this state?

O has 2 possible moves, and this element of choice makes our AI’s calculations more complex. It’s easy for a human to see that O should play in square 1, since this allows it to salvage a draw. But we need to teach this intuition to our AI.

Let’s think back to our tree, and propagate up its branches the information that we already know. If O plays in square 2, this results in the above state, to which we already gave a score of +10 (remember that high scores are always good for X, low scores are good for O). If O instead plays in square 1, we can repeat our analysis for the resulting state. If X plays “perfectly”, in the only square available to it, the game will be a draw, and the final state will be given a score of 0. Our AI propagates this 0 up the tree branches, and gives the state after O plays in square 1 a score of 0 too.

We have now methodically shown that O has a choice between 2 moves, and that these moves result in states with scores of +10 and 0 respectively. Low scores are good for O, so O should choose the move that results in the state with the minimum score. This is state 2. Our AI therefore propagates state 1’s 0 score up the tree to our original state, and assigns this original state a score of 0 as well. We have now systematically, if longwindedly, re-proven our original intuition: with optimum play from both sides, the original state will be a draw.

We can repeat this process for states earlier in Tic-Tac-Toe games. Suppose that we want to calculate the best move in the following state, 1 move earlier:

We’ve already shown that the state if X plays in square 3 has a score of 0. We can repeat our above analysis for the states that would result from X playing in the other two squares, and then choose the move with the maximum score (since X is trying to “maximin”).

The scores of the terminal states are the source of all knowledge. Our AI spreads this knowledge using the minimax algorithm; from the ends (or leaves) of the tree, all the way up to the very start of the game. It uses the scores from the terminal states (call them, say, level 0) to calculate scores for states one move earlier (level 1). It uses these level 1 state scores to calculate level 2 state scores, level 2 to calculate level 3 and so on.

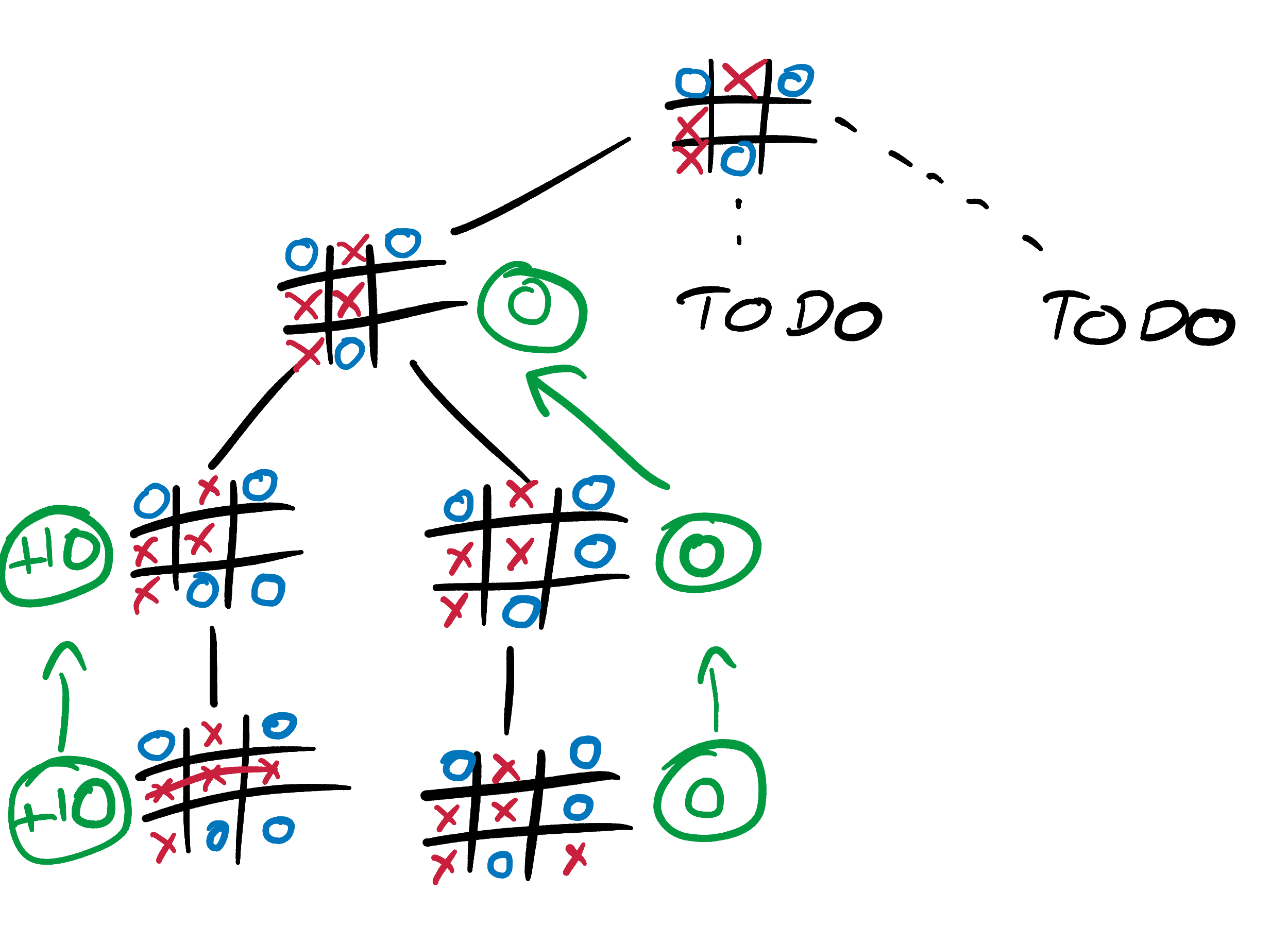

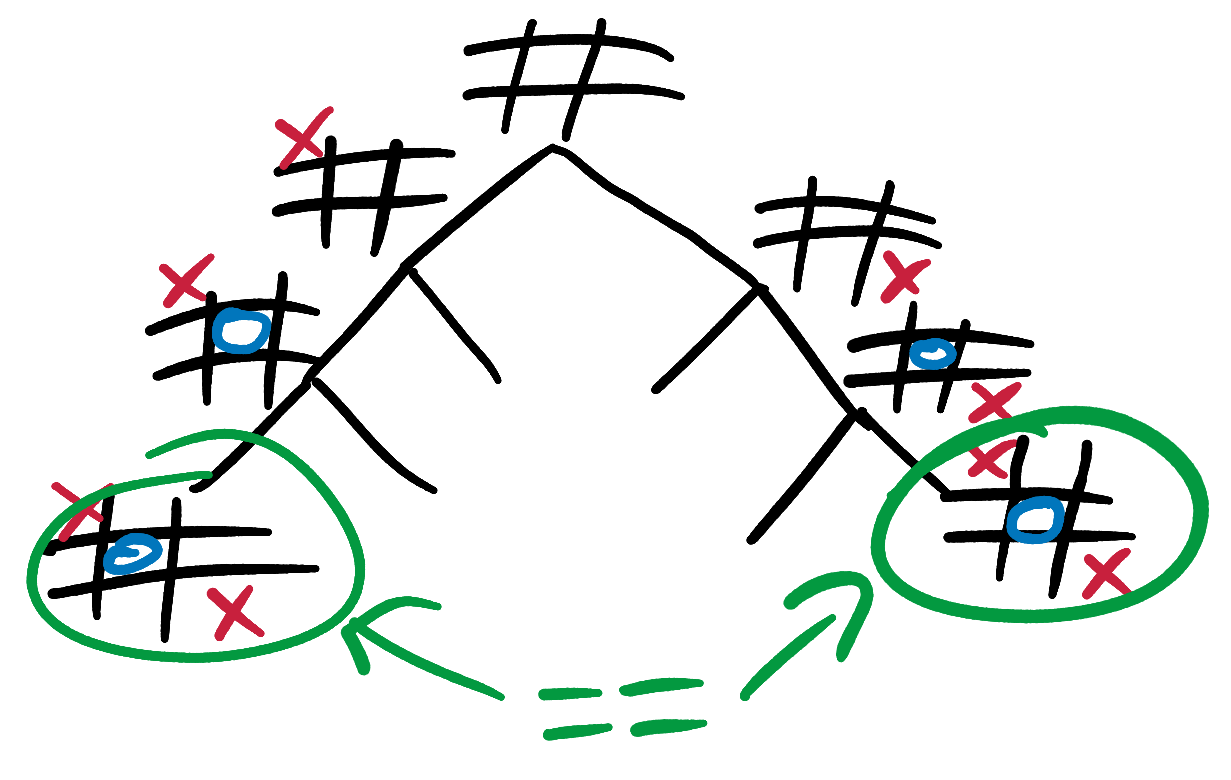

This image is a very good explanation of minimax.

Writing the minimax algorithm

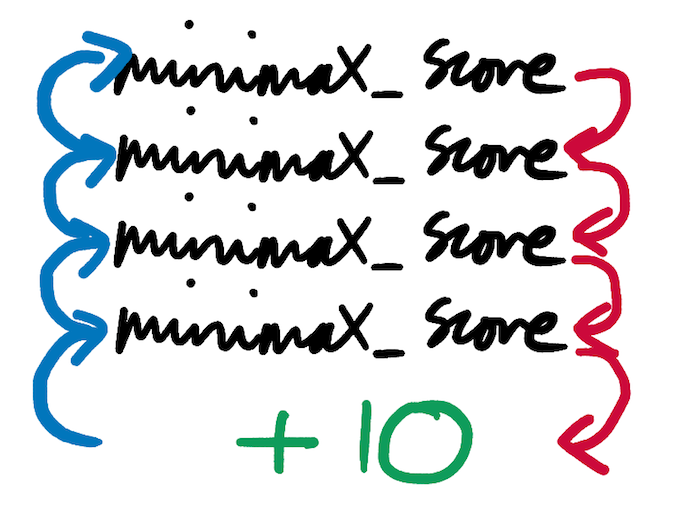

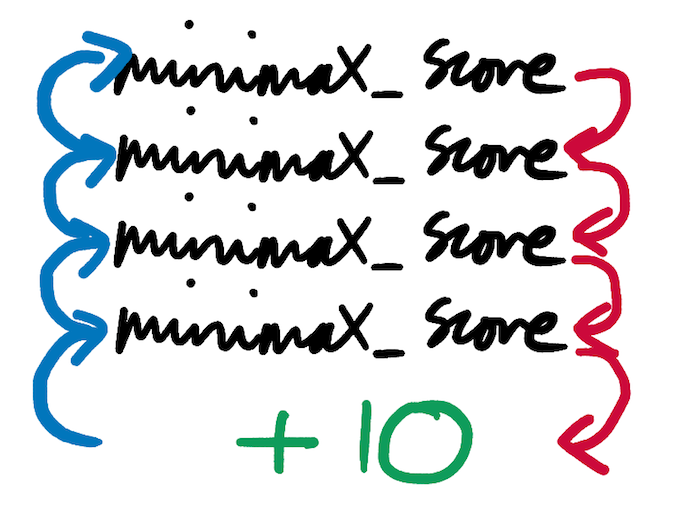

Let’s rewrite the above 10 paragraphs as pseudo-code. The code will make use of a technique known as recursion: a function that calls itself, possibly many times in a row. Recursion is nothing special or magical - it’s just code - but it can be hard to reason about if you haven’t come across it before. Google “recursion fibonnaci sequence” if you’d like a more detailed introduction.

# For simplicity we'll assume that our AI

# always plays as X.

#

# "X" for Xpert!

# "O" for Opponent!

#

# `board` is a 2-D grid of the state to be scored

# `current_player` is the player whose turn it is

# ('X' or 'O')

def minimax_score(board, current_player):

# If `board` is a terminal state, immediately

# return the appropriate score.

if x_has_won

return +10

else if o_has_won

return -10

else if is_draw

return 0

# If `board` is not a terminal state, get all

# moves that could be played.

legal_moves = get_legal_moves(board)

# Iterate through these moves, calculating a score

# for them and adding it to the `scores` array.

scores = []

for each move in legal_moves:

# First make the move

new_board = make_move(board, move, current_player)

# Then get the minimax score for the resulting

# state, passing in `current_player`'s opponents

# because it's their turn now.

#

# You may notice that `minimax_score` is calling itself -

# this is known as "recursion".

opponent = get_opponent(current_player)

score = minimax_score(new_board, opponent)

scores << score

# If `current_player` is X (our AI), then they are

# trying to maximize the score, so we should return

# the maximum of all the scores that we calculated.

if current_player == 'X'

return max(scores)

# If `current_player` is O (our AI's opponent), then

# they are trying to minimize the score. We should

# return the minimum.

else

return min(scores)

Here’s another description of the minimax_score function, this time structured as bullet-points:

- If X has won, immediately return +10

- If O has won, immediately return -10

- If the state is a draw, immediately return 0

- For each possible move for the current player, get the state that would result if that move was made

- For each of these states, use the

minimax_score function to calculate its score. This is an example of “recursion” - a function calling itself. Store all of these scores in an array

- If X is the current player, return the max of the scores resulting from each possible move (maximin-ing)

- If O is the current player, return the min of the scores (minimax-ing)

These descriptions of the minimax algorithm take a slightly different perspective to that of the previous section. In the previous section we began our analysis from terminal states, at the bottom of the tree. We then climbed up the tree using minimax, propagating scores up as we went.

However, our AI has to start its calculations from the early-game state it is given, which may be a long way from the terminal states on the leaves. Because of this, it structures its work in 2 “phases”.

Phase 1 is the unrolling of the recursion; the building of the tree. Each call to minimax_score in our pseudo-code begets several more calls to minimax_score, each of which begets several more calls, each of which… None of these calls return until they hit a terminal state that triggers one of the 3 if-branches at the top of the function. Hitting one of these branches allows minimax_score to immediately return -10, 0 or +10, without needing to make any further recursive calls to itself.

Phase 2 is the recursion rolling back up, once the tree has reached the terminal states that populate its leaves. This is the phase that we looked at in most depth in the previous section. As massively-nested calls to minimax_score start to return, the calls that spawned them can return too, and so on and so on back up the stack, until the original call returns a single number.

In the pseudo-code above, the 2 phases are actually interleaved with each other. If you trace the program through step-by-step, you’ll find that some calls to minimax_score start to return before others have even been made. The tree is constantly being both rolled and unrolled. However, the phase-based model is still valid and useful for understanding the algorithm. It would be completely possible to refactor our code to more sharply divide the phases; in fact, we’ll look at how to do this in the extensions section. As always, both approaches have their advantages and disadvantages.

It’s time to act

Write a perfect tic-tac-toe AI called minimax_ai. Re-read this section if and inevitably when you need to refresh some of the details. Google “minimax” and “tic-tac-toe minimax” and read other takes on the algorithm. My example code is there if you get truly stuck.

Tic-Tac-Toe is a simple game, but playing through every single possible game is still a lot of work, even for a modern, powerful computer. It can take over 10-20s for minimax to decide on a move at the very start of the game. In the extensions section, we’ll look at how to use caching to speed up the execution of our program by approximately 10x. To save yourself some time in the meantime, start by testing your AI using late game states. In particular, test with late game states where there are some moves that are clearly bad and some that are clearly good. Make sure that your AI only ever chooses the good ones.

There are several ways you can build confidence that your AI really is perfect.

- Play against it. Try to beat it, try to let it beat you.

- Battle 2 perfect AIs against each other. Since Tic-Tac-Toe is a draw with perfect play, every game they play should be drawn

- Battle a perfect AI against a worse AI. The perfect AI should never lose, and should sometimes win

- Write “unit tests” that assert that your AI makes the best move (or avoids the worst move) in a range of tricky states

Once you’re convinced that your AI is perfect, show it off to your family, friends and enemies. Especially your enemies. Once they see your power they won’t mess with you ever again.

Final task - say hi!

If you’ve successfully made it this far then I’d love to know! I’m going to be making more advanced-beginner projects like this, and I’d like to understand how to make them as useful as possible. Please send me an email to tell me about your achievement, I’d love to hear from you. You can also sign up for my mailing list at the bottom of this page to find out when I publish more advanced-beginner projects. I’m planning on writing at least 1 per month.

Once you’ve sent me that quick message, it’s time to move on to the extensions. They are even harder than the rest of the project, and come with even fewer pointers. Don’t be afraid to spend a lot of time just thinking and sketching out brief, experimental snatches of code.

NEW

Subscribe to my new "Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners"

newsletter to receive concise weekly emails containing specific,

real-world ways to make your code cleaner and more professional.

Each week I review code sent to me by one of my readers. I highlight

the things that I like, discuss the

things that I think could be better, and offer suggestions for how

the author could make their code cleaner and easier to work with.

Subscribe now to receive these invaluable improvements in your inbox

every week, completely free.

Extensions

Extension 1. Make our AI streetwise

Our AI chooses its moves based on the assumption that its opponent will play perfectly. This is sensible. Assuming the worst and respecting your opponent will win you many wars, both on and off the Tic-Tac-Toe board.

However, this mindset means that our AI doesn’t even consider the possibility that its opponent might make a mistake. It doesn’t bother trying to find tricksy moves that require precise play to defend against. As far as it’s concerned, its opponent’s play will always be precise, so what’s the point?

For example, to our AI, the first move of the game is entirely unimportant, because all Tic-Tac-Toe first moves result in a draw with perfect play. Since our AI assumes that all play is always perfect, it gets quite nihilistic, seeing no reason to prefer any move over any other. It sees all moves as equally good, bad, or pointless.

If its opponent really is perfect, then our AI is right and this choice really doesn’t matter. But if there’s any chance that its opponent might make the occasional blunder then our AI should give it as much rope to hang itself as possible.

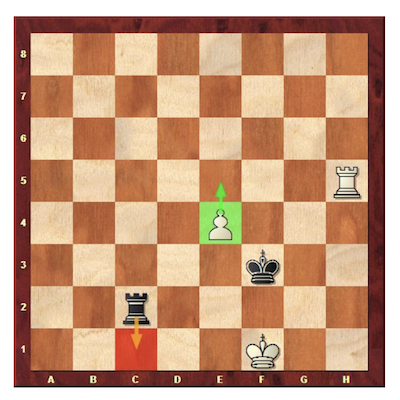

White: GM Magnus Carlesen (World Champion)

Black: GM Merab Gagunashvili

Our AI should hand out this rope by choosing moves that demand precise responses. It should prefer to play in the corners, and it should try to get 2 pieces in a row, even if its opponent can block it from getting the third if they’re paying any attention whatsoever.

A good way to add these kinds of preferences to your AI is to update the way that it calculates state scores. We still want it to choose winning moves and avoid losing ones above all else. But now we want it to use heuristic rules to break ties when choosing between 2 or more moves with equal scores.

There are at least 2 ways to implement this feature. First is to tweak the score that our AI is already calculating using tie-breaker rules. We keep the scores for winning, losing and drawing states at +10, -10 and 0 respectively, and then add and subtract a tenth of a point here and there for states with tricksy features like having 2 pieces in a row. Your AI will still always choose winning moves (base score of +10) when they exist, but if all moves theoretically lead to draws (base score of 0) then it will choose the craftiest one (with a score of eg +0.2).

The alternative (and in my opinion better) approach is to keep tie-breakers and deal-breakers completely separate. In this approach we still have the same heuristic rules for calculating tie-break scores. But we don’t add them to the main, deal-breaker score. Instead, we return the tie-break score as a second distinct, value. Your AI chooses the move with the highest first score (+10/-10/0), and only ever uses the second if it needs to break a tie in the first.

This makes for slightly clearer code that will be harder to accidentally introduce bugs into. The first approach relied on you choosing your numbers carefully. If you accidentally made it possible for a losing state to have enough heuristic advantages to get a higher score than a drawn one, your perfect AI would not be so perfect anymore. But by cleanly separating out the different levels of decision-making, the second approach makes this kind of bug impossible.

Repeatedly fight your street_smart_minmax_ai against your minmax_ai (see section 5b). What should the results be? What about if you compare the results of street_smart_minmax_ai and minmax_ai when they battle against our earlier, inferior AIs?

Extension 2. Speed up execution using caching

As it is currently written, our minimax AI is very slow and wasteful. When it reaches the same state on 2 different branches via 2 different move orders, it has no way to share its calculations. It blithely repeats the exact same calculations, getting the exact same results every time.

To fix this and speed up our program, we can use a cache to store and share state scores across branches. This saves us from calculating a score for the same state twice:.

cache = {}

def minimax_score_with_cache(board)

# Turn the board into a string so

# it can be used as a dictionary key

# to access our hash.

#

# This conversion can be done any way

# you like so long as each board

# produces a unique string.

board_cache_key = str(board)

# Only calculate a score if the board

# is not already in our cache.

if board_cache_key not in cache:

score = ... # MINIMAX CODE GOES HERE!

# Once the new score has been calculated,

# stuff it into the cache.

cache[board_cache_key] = score

# Finally, return the score from the cache.

# Either it was already there, or it wasn't

# and we just calculated in in the block

# above.

return cache[board_board_cache_key]

print minimax_score_with_cache(my_board)

Add caching to your AI. Compare its speed with and without caching, especially for the first move of the game. You should see close to a 10x speedup. Print out the cache and see what it looks like.

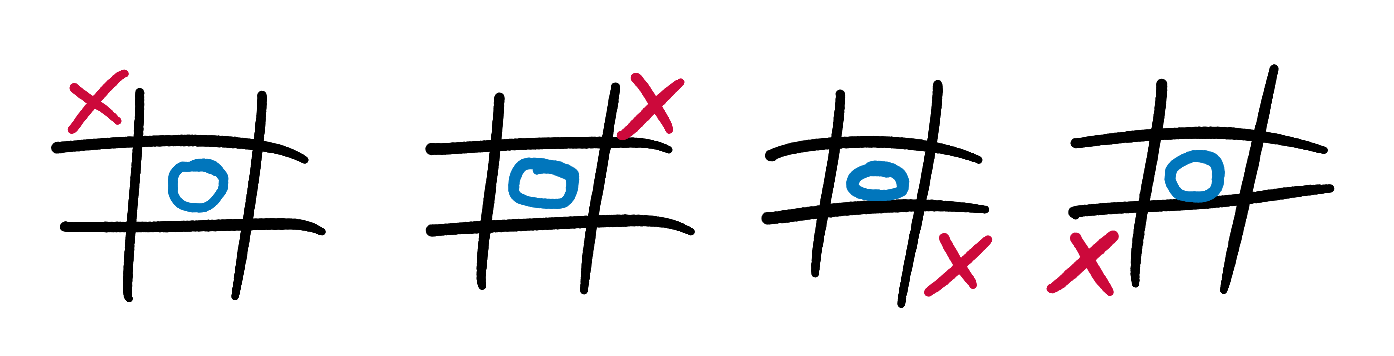

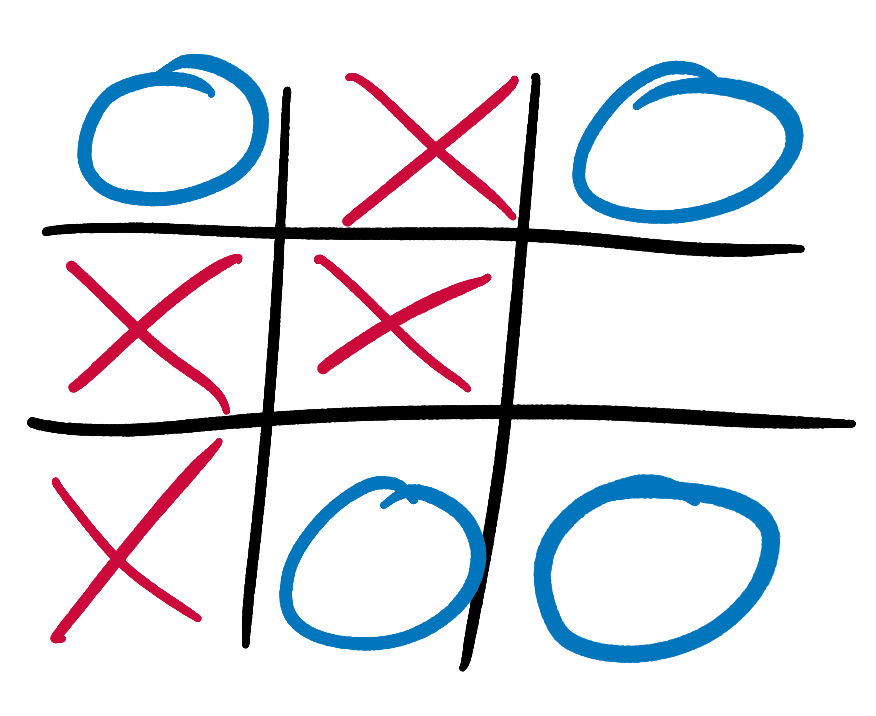

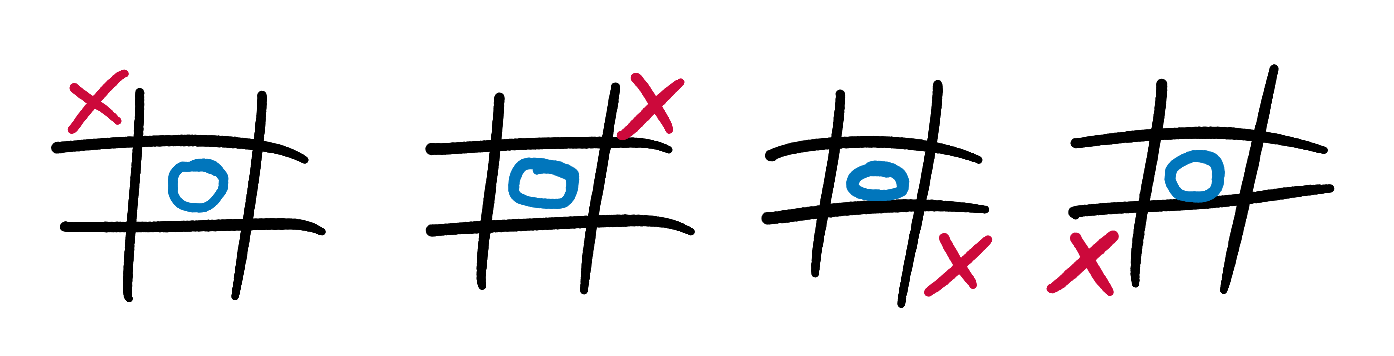

Extension to the extension - from a scoring point of view, these 4 states are all identical:

If we know the score for the first state, we can re-use it for the other three states without having to do any extra calculation. Try updating our caching mechanism so that it doesn’t have to re-calculate scores for states that are mirror-images or rotations of each other. You could do this by inserting multiple entries into the cache when you calculate a score, or by calculating the board_cache_key string in such a way that mirror-images and rotations all produce the same key.

(This is probably my favorite piece of this entire project)

Extension 3. Speed up execution using alpha-beta pruning

Alpha-beta pruning is another way to speed up execution of the minimax algorithm. Google it, read about it, implement it, measure the speed up. Start by doing it separately to caching, then try combining them.

Extension 4. Speed up execution using pre-calculation

Caching and alpha-beta pruning are good ideas, but they’re nothing compared to simply precalculating the best move for every state and storing it in a massive file. Write a program that uses minimax to precalculate the best move in every possible Tic-Tac-Toe state and saves this information to a file (perhaps as JSON). Then write a new AI function that simply reads this file when it starts up and uses it to instantly look up the best move for any state, without any need for any further minimax-ing.

Extension 5. Apply minimax to other games

You can use the exact same minimax algorithm to play other games perfectly too. In theory you could use it to solve chess, go, or any other perfect information game (one in which nothing is secret) that can be taught to a computer. However, as games get more complex, the amount of computing power required to minimax them quickly explodes. You can look up the exact stats yourself, but in order to thoroughly minimax all games of chess of 40 moves or less, I believe that you’d have to run a supercomputer the size of the universe from now until the end of time.

Assuming that you don’t have such a machine and have only a limited amount of time to devote to your programming pursuits, try minimax-ing simplified versions of your favorite games. Connect 4 on a 5x5 board, or chess on a 4x4 board with nothing but kings and pawns.

This is the second and final part of our quest to build an unbeatable, perfect Tic-Tac-Toe AI. In part 1 we wrote a Tic-Tac-Toe engine that allowed two human players to play against each other. In part 2, we’re going to use the minimax algorithm to build a flawless AI.

Subscribe to my new "Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners" newsletter to receive concise weekly emails containing specific, real-world ways to make your code cleaner and more professional.

Each week I review code sent to me by one of my readers. I highlight the things that I like, discuss the things that I think could be better, and offer suggestions for how the author could make their code cleaner and easier to work with.

Subscribe now to receive these invaluable improvements in your inbox every week, completely free.

First we’re going to warm up by writing some simpler AIs that choose their moves using if-statements and rules of thumb. As we do this we’ll build out the code that connects our computer players to our existing Tic-Tac-Toe engine. Once we’ve got our warmup AIs working and have written and verified this generic infrastructure we’ll be ready to give our total focus to our final goal: making a perfect Tic-Tac-Toe AI.

As with all my projects, I’m going to leave all of the difficult work to you and throw you right in at the deep-end. But I’ll also give you gentle reminders on how to swim, as well as some new tips on swimming best practices. If you do get completely stuck then I’ve written some example code. You can always use it to point yourself back in the right direction.

Today’s lesson - Interfaces

We’re going to write several different Tic-Tac-Toe AIs, each of which will choose their moves using different strategies of varying degrees of complexity. And we won’t be the only ones doing this. We also want to be able to challenge your friends and family to a duel - your best AI against theirs. We want them to be able to build their AIs on their own, and to be able to easily plug them into our Tic-Tac-Toe engine so that we can have a rumble. Then we want to crush their AIs and their spirits. And we will. Mark my words. We will crush them.

This raises an important question. We’re going to be writing many different AIs. Your enemies are going to be writing AIs of their own too. How can we ensure that all of these algorithms are able to talk to each other? How can we ensure they they can all plug into our Tic-Tac-Toe engine, even though they were all developed independently and take completely different approaches to choosing their moves?

We will solve this problem and make sure that all of our code is compatible by using interfaces. An interface is a definition of the way in which different components of a system communicate with each other. For example, the interface between you and a coffee shop is that if you give the coffee shop the right amount of money, they will give you a coffee.

The interface between you and the dry cleaners is that if give the dry cleaners some clothes, they will give you a ticket. And if you wait a few days and then give them a ticket and the right amount of money, they will give you back your clothes minus any foul stenches they may have had.

Interfaces are powerful because the component on one side of an interface boundary doesn’t need to know any details about how the component on the other side works. Another real-life example: the interface between your headphones and your laptop is that if you plug a 1mm jack into your laptop, your laptop will send that jack electrical signals in a pre-agreed format that can be converted into sound. But your laptop doesn’t actually care what your headphones do with these signals after they’ve crossed the interface boundary, and your headphones don’t care how the signals were originally generated. They could have come from YouTube, Spotify, Skype or Minecraft. As long as the laptop and headphones conform to the agreed interface, they can generate their inputs and outputs in any way that they please.

Similarly, you don’t have to care how the coffee shop produced the coffee it gave you (so long as everyone involved washed their hands and was compensated according to your ethical standards), and the coffee shop doesn’t have to care where your money came from. You could have taken it out of an ATM (your interface with your bank), found it on the street, or received it from the US Federal Reserve in exchange for toxic mortgage-backed securities as part of the 2008 TARP bailout. The implementation of an interface - how a component lives up to its end of the deal - is completely separate from what the deal actually is.

Poorly-designed interfaces are messy and hard to understand. Take the IRS. If you fill out a trillion forms, do some maths, write a check, post it to the government, and phone them up a few days later to make sure that they got it, then the IRS will mark your taxes as paid. This interface is difficult and stressful, and products like TurboTax exist to provide a better one. If you upload some documents, click some buttons, abdicate some responsibility, and pay TurboTax $100, then they’ll figure out the rest. TurboTax does also lobby the Federal government to make sure that your direct interface with the IRS is as bad as possible in order to keep you paying them that $100 every year, but this doesn’t diminish their utility as a teaching example. Once you’ve clicked “Submit” you don’t care how they get your tax return to the IRS, so long as they do. They could have an army of Mechanical Turks, a very messy but unfailingly accurate PHP program, or infinite monkeys with infinite CPA qualifications.

Interfaces in code

Interfaces are everywhere in code too. Every function is an interface - “you give me X and Y and I’ll return you Z”. It’s very possible and very useful for multiple functions to share the same interface.

For example, imagine that you’re building a system that makes personalized movie recommendations. You want your system to be diverse and imaginative, and so you want it to have several different methods of generating recommendations.

You would be well-advised to construct your system out of functions that each use different techniques to recommend movies, but all conform to the same interface. This interface could be something like “you give me the list of movies that a user liked, and I’ll return the 3 movies that I think they should watch next.” One function could look for movies with similar names to those that the user liked. Another could be looking for movies that were liked by other users with similar tastes. And a final one could always return ["Con Air", "Con Air", "Con Air"], because there is no better movie than “Con Air”. Even though all of these functions do extremely different things behind the scenes, they all conform to the same interface. And because they all conform to the same interface, new recommendation algorithms can be dropped in and swapped out, with no new custom code required to plug them in.

# By using "first-class functions", we

# can just add our new recommender functions

# to this list

recommender_functions = [

similar_names,

similar_tastes,

con_air

]

for f in recommender_functions:

print f(user_favorite_movies)

# => ["American Beauty", "American Beauty 2", "Quest for Beauty"]

# => ["Aladdin", "Frozen", "Wall-E"]

# => ["Con Air", "Con Air", "Con Air"]

We are going to specify our own interface that defines how our Tic-Tac-Toe engine and our Tic-Tac-Toe AIs communicate with each other. Right now our engine has sections of code that take care of printing the board, checking for wins, checking for draws, alternating sides, checking for legal moves, and getting moves from the human players. We will keep almost all of this code the same; the only change we will make is to swap out the section that gets moves from humans and replace it with an AI.

We’ll decree that an AI function should accept 2 arguments - a board and the ID of the side whose move it is (O or X). The function should return the co-ordinates of the square that the AI would like to play in. As long as a function conforms to this interface - “you give me a board and an ID and I’ll give you back a co-ordinate” - we can easily plug it into our engine, without our engine needing to know anything about how it works behind the scenes. The function can decide on its move in any way it likes, using anything from a neural network to a Twitter poll to a complex system of levers and pulleys. In this project we’ll write AI functions that calculate their moves using stacks of if-statements, human decisions, and the elegant and unbeatable minimax algorithm. However, these are all implementation details that our engine won’t have to know or care about.

Note that in some programming languages, like Java and Go, interface is a special language keyword with a specific meaning. We are using the word in a more general sense. In many other languages, like Python and Ruby, you don’t have to write any code that officially “declares” an interface. You just tell other programmers who want to add new components to your system how everything works and which interfaces they need to conform to. If they do then everything else will Just Work.

Why it’s good to think in interfaces

Thinking about your programs in terms of interfaces makes your code neater and easier to extend. It pushes you towards designing your system as a series of discrete components that are each responsible for a small number of things, and that only communicate with each other through well-defined, well-understood pathways. This means that changing one component is less likely to cause bugs with another. As long as the component you changed still conforms to all the same interfaces, it will still interact with the rest of your system in the same way. A good sign that your code is making good use of interfaces and components is that you can easily sketch its structure using boxes and arrows, and don’t need too many arrows.

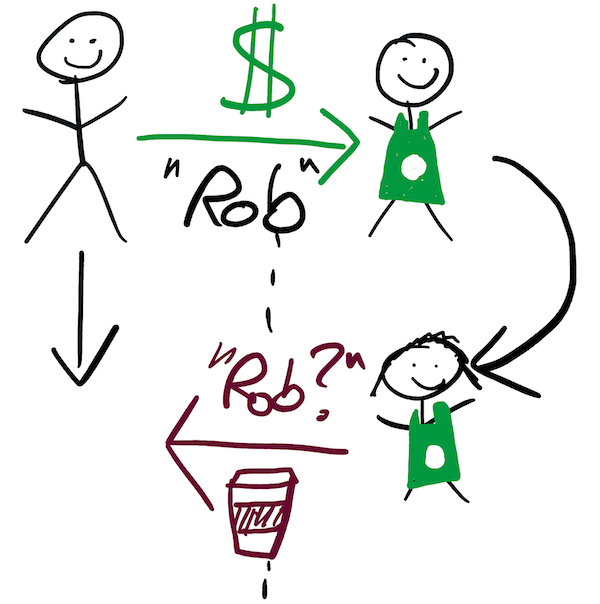

A world without well-defined interfaces is a world in which everything directly depends on the details of everything else. Complex or non-existent interfaces can sometimes be justified. In many Starbucks coffee shops you start as normal, by giving the barista money and an order in flawless Italian. But then, then instead of immediately receiving your coffee, you have to go and stand in the coffee bullpen until your name is called. This interface between you and Starbucks is more complex than the simple exchange of cash and caffeine that we discussed previously. It requires you, the user, to do more work, and to understand something about the internal workings of Starbucks. It does, however, increase the shop’s overall coffee throughput (measured in macchiatos per minute), which can only be good for busy bean lovers and holders of $SBUX stock.

You could argue that the increasing popularity of chain restaurants and coffee shops is indicative of people’s desire for consistent, well-defined interfaces with the world. They don’t want to have to care whether the yam harvest was good or bad this year or which days Julian is in the kitchen. They want to be served within 30 minutes and back out the door within 75. They want to pay by inserting their credit card into a standardized device and putting in a magic code. And they want to not have to worry about their family’s reputation in the community whilst they get drunk enough to forget about all the Jira tickets that await them the next morning. However, this is probably reading a little too much into decent, reasonably-priced pizza. A consistent interface doesn’t mean that everything is the same - it means that the way you interact with it is.

With a million metaphors under our belt, let’s build some Tic-Tac-Toe AIs that all conform to a consistent interface, and see for ourselves why interfaces are so helpful.

1. AI that makes random moves

We’re going to start by writing one of the simplest AIs possible. This AI will look at the board, find all the legal moves, and return one of them at random.

We’ll write a function called random_ai that conforms to our AI interface. This means that it accepts 2 arguments - a Tic-Tac-Toe board and the current player - and returns the co-ordinates of a move. You may notice that random_ai does not actually need to know the current player, since all it is doing is using the board to choose a random legal move. However, in order to conform to our Tic-Tac-Toe AI interface, it still needs to accept the current player as an argument. It can then simply ignore it.

Write random_ai now. Try it out on some test boards:

board = [

['X', 'O', None],

['O', 'O', None],

['X', None, None]

]

print random_ai(board, 'X')

print random_ai(board, 'X')

print random_ai(board, 'X')

print random_ai(board, 'X')

# => should print a random legal move each time

Make sure that it always returns a legal move.

Then plug random_ai into your Tic-Tac-Toe engine from the first part of this project. Your engine probably has a line that looks something like:

move = get_move()

get_move was the function that was responsible for getting the human player’s next move. Because of the delightfully modular way in which we constructed our Tic-Tac-Toe engine, you should be able to instantly swap in your new robot by changing this line to something like:

move = random_ai(board, current_player)

The rest of your program should continue to work as normal, with no further changes required. Run your program a few times and watch it play some random games against itself.

2. AI that makes winning moves

Let’s make a second, slightly more intelligent AI. Write a finds_winning_moves_ai function that returns a winning move if one exists, and a random move otherwise. It too should conform to our AI interface, meaning that it accepts 2 arguments - a Tic-Tac-Toe board and the current player - and returns the co-ordinates of a move. Unlike random_ai, finds_winning_moves_ai will need to use the current_player argument, because it needs to know whose winning moves it should be trying to find.

Once again, try out your finds_winning_moves_ai function manually on some test boards:

board = [

['X', 'O', None],

[None, 'O', None],

['X', None, None]

]

print finds_winning_moves_ai(board, 'X')

print finds_winning_moves_ai(board, 'X')

# => should always print (1, 0)

print finds_winning_moves_ai(board, 'O')

print finds_winning_moves_ai(board, 'O')

# => should always print (2, 1)

Then update your main program with your smarter AI. Because finds_winning_moves_ai conforms to the same interface as random_ai, this will be as straightforward as changing:

move = random_ai(board, current_player)

to:

move = finds_winning_moves_ai(board, current_player)

Powerful things, these interfaces. Run your smarter AI against itself a few times. How should the results of these games be different to those played by 2 random_ais? Should you see more or fewer draws?

3. AI that makes winning moves and blocks losing ones

This is the final approximate, or heuristic AI that we’ll write before starting work on our flawless minimax algorithm. Write a finds_winning_and_losing_moves_ai that conforms to our AI interface. finds_winning_and_losing_moves_ai should return, in order of preference: a move that wins, a move that block a loss, and a random move.

Test it out, plug it in. How should the results of these games be different to those between 2 finds_winning_moves_ais? Should you see more or fewer draws?

4. Refactoring the human

Now let’s bring back the human player. Remember, the point of an interface is that you don’t have to care how the thing behind the interface does its work. All of the functions that we’ve written so far are powered by highly sophisticated artificial intelligence, but it’s also completely permissible for us to define a function that conforms to the same interface but is powered by a real, fleshy human.

Write a human_player function that gets its move co-ordinates by asking for input on the command line, in the same way as you did in the first part of this project. The only difference is that this time human_player should conform to the AI function interface. Test it out, plug it in, play some games against yourself.

5. Different sides, different AIs

So far we’ve only been battling AIs against copies of themselves. But things start to get really interesting when you have different algorithms face off against each other.

First we’ll have to tell our program which algorithms should go in the arena. We could do this in the same way we’ve done it so far - directly changing the guts of the code - but this is not very satisfactory or user-friendly. Instead, we’ll give our AIs names - strings like "random_ai" and "find_winning_moves_ai". We’ll pass the (possibly different) names of the O and X AIs into our program (perhaps via the command-line), and use them to select the logic that should be used.

python tictactoe.py random_ai find_winning_moves_ai

We can convert these names into algorithms in several different ways. The approach that we will start with is to use if-statements in your main game loop:

# In your main game loop:

if player_name == 'random_ai:

move = random_ai(board, current_player)

else if player_name == 'find_winning_moves_ai':

move = find_winning_moves_ai(board, current_player)

# ... etc

This approach is a little verbose and cumbersome, but it works and is completely adequate. If you’re curious then use Google to find out how to select AIs with slightly more style using first-class functions and classes.

We’ll also have to update our main program to alternate between the different algorithms that are battling against each other as we alternate between taking turns for X and O. Do this now.

Once you’ve written this code, fight a random_ai against a finds_winning_and_losing_moves_ai a few times. The more intelligent AI should have a significant advantage.

5b. Repeated battles

Add a way to fight 2 AIs against each other thousands of times to find the average win percentages. I’d suggest structuring this like:

def play(player1_name, player2_name):

# Returns:

# * 0 if the game is drawn

# * 1 if player 1 wins

# * 2 if player 2 wins

def repeated_battle(player1_name, player2_name)

# Repeatedly call the `play` function and tally the results

This is just an experiment to see how much effect different rules and optimizations have on an AI’s skill-level. It’s not essential, and you can skip it if you want to move straight onto the final milestone: building a perfect AI.

6. Building a perfect AI

I used to play in a lot of chess tournaments. They were played in vast, hushed halls, with no sound other than the gentle clacks of knights moving to F3. If you wanted to post-mortem your game after you had finished, there was usually a small analysis room off to the side. Here triumphant victors and grumpy losers pored over the past, trying to show how smart they had been or work out what they could have done better. The air was saturated with a gentle hubbub of “if I go there, she goes there; but if she goes there, I go there!” Players were looking at all the possible moves that they could have made in a position, and for each move trying to find their opponent’s best response. For each best response they tried to find the best counter-response, and so on and so forth until the game had ended or the result was no longer in doubt.

Assuming that your opponent will play optimally and trying to find the best responses to their best responses is pretty much what the minimax algorithm does. The only difference is that we’re going to use computers to do it perfectly and much, much faster.

To begin the minimax algorithm, our AI will build a tree of all 250,000 possible games of Tic-Tac-Toe.

On its own, this tree won’t tell our AI anything useful. It will describe all the games of Tic-Tac-Toe that could ever be played, but it won’t say anything about how to use this information to make flawless moves. Possession of mountains of raw facts is not the same as knowledge of what to do with them. Only with the help of the minimax algorithm can our AI convert this Tic-Tac-Toe tree from dumb data into profound sylvan wisdom.

Minimax or maximin?

As Sun-Tzu once said (or was it my dad?), in order to be a good Tic-Tac-Toe player, you must see the battlefield through the eyes of your opponent. We will take to heart the wisdom of the ancients, and will train our AI in the ways of the most ruthless warrior the world has ever seen (or was it Sun-Tzu?).

In order to choose its moves, our AI will put itself in the mind of its opponent. It will see that it’s no good playing moves that will win if your opponent plays foolishly, but lose if they play well. You must assume the worst. You must assume that your opponent will choose the moves that maximize their own outcome, and you must choose the moves that MINimize these MAXimum outcomes for your opponent (hence: minimax). Leave them with no good choices, and assume that they will try to do the same to you.

If you prefer to think positively then you can also see this as MAXimizing your own MINimum outcome (maximin). Maximin and minimax are the same side of the same coin, seen from opposing perspectives.

Our AI will start by considering all of the current position’s legal moves, and assigning the position resulting from each move a numerical score. It will calculate these scores by working out what the result of the game would be if it were played out between two equally perfect players. Finally, it will choose the move that gives it the maximum score. This sounds straightforward enough, except for one tiny detail.

How exactly does it calculate those scores?

Scores

Our AI will need to be able to assign scores to 2 types of positions: those in which the game has finished (which we will refer to as terminal states), and those in which it has not. Terminal states are much simpler than non-terminal ones, so let’s start with them.

Scoring terminal states

If a terminal state is a win for our AI, it gets a score of +10. If it’s a loss for our AI, it gets a score of -10. If it’s a draw, it gets a 0. That’s all there is to this rule. It applies only to completely terminal, game-over state. It does not apply to states in which the result is certain but has not yet been played out. For example, we can use the rule to immediately assign the following state a score of +10, since our AI (playing as X) has already won:

But we could not use it for the following state:

It’s clear to us savvy humans that our AI (still playing as X) is about to win. But it has not yet delivered the coup de grace, and the game is not yet officially over. We therefore can’t apply our terminal state rule, because we aren’t in a terminal state. We could score this state using another big ol’ pile of branching if-statements to work out if there is a winning move available, like we did in the previous iterations of our AI. But this won’t help us with more ambiguous states in which the eventual outcome is less clear.

We need a general rule that can score all non-terminal states, not just those in which the future result is obvious. We’re about to get a bit abstract, so pack a lunch and tell a friend to alert the police if you’re not back by 5.

Scoring non-terminal states

Our AI will score non-terminal states by working out what the outcome would be if both players finished the game by playing perfect Tic-Tac-Toe, and assign the state a score corresponding to that outcome. Sounds sensible enough. But this brings us right back to the very question that we are trying to solve - how exactly does one play perfect Tic-Tac-Toe? Don’t worry, we’re getting closer.

Minimax requires our AI to walk along the branches of its Tic-Tac-Toe tree, propagating concrete scores from the terminal states on the leaves up to more uncertain-looking early-game states. Let’s try some examples. It’s X’s turn to play. What score should our AI, playing as X, give this state?

The game is not yet over, so we can’t use our simple rule for game-over states from above. But X has only one possible move, and it results in a glorious victory. We can therefore say that with perfect play from both sides X will win. This is a slightly odd statement, since X has only one possible move and so has no choice but to play perfectly. But it’s still true, and it means that our AI should give this state a score of +10, even though it is not terminal. Our AI now knows that if it can reach this state then the game is as good as won, and should be just as excited about reaching this state as one in which it already has 3 Xs in a row.

Let’s rewind the game by one move and climb one branch up the Tic-Tac-Toe tree. This time it’s O’s turn. What score should our AI, still playing as X, give this state?

O has 2 possible moves, and this element of choice makes our AI’s calculations more complex. It’s easy for a human to see that O should play in square 1, since this allows it to salvage a draw. But we need to teach this intuition to our AI.

Let’s think back to our tree, and propagate up its branches the information that we already know. If O plays in square 2, this results in the above state, to which we already gave a score of +10 (remember that high scores are always good for X, low scores are good for O). If O instead plays in square 1, we can repeat our analysis for the resulting state. If X plays “perfectly”, in the only square available to it, the game will be a draw, and the final state will be given a score of 0. Our AI propagates this 0 up the tree branches, and gives the state after O plays in square 1 a score of 0 too.

We have now methodically shown that O has a choice between 2 moves, and that these moves result in states with scores of +10 and 0 respectively. Low scores are good for O, so O should choose the move that results in the state with the minimum score. This is state 2. Our AI therefore propagates state 1’s 0 score up the tree to our original state, and assigns this original state a score of 0 as well. We have now systematically, if longwindedly, re-proven our original intuition: with optimum play from both sides, the original state will be a draw.

We can repeat this process for states earlier in Tic-Tac-Toe games. Suppose that we want to calculate the best move in the following state, 1 move earlier:

We’ve already shown that the state if X plays in square 3 has a score of 0. We can repeat our above analysis for the states that would result from X playing in the other two squares, and then choose the move with the maximum score (since X is trying to “maximin”).

The scores of the terminal states are the source of all knowledge. Our AI spreads this knowledge using the minimax algorithm; from the ends (or leaves) of the tree, all the way up to the very start of the game. It uses the scores from the terminal states (call them, say, level 0) to calculate scores for states one move earlier (level 1). It uses these level 1 state scores to calculate level 2 state scores, level 2 to calculate level 3 and so on.

This image is a very good explanation of minimax.

Writing the minimax algorithm

Let’s rewrite the above 10 paragraphs as pseudo-code. The code will make use of a technique known as recursion: a function that calls itself, possibly many times in a row. Recursion is nothing special or magical - it’s just code - but it can be hard to reason about if you haven’t come across it before. Google “recursion fibonnaci sequence” if you’d like a more detailed introduction.

# For simplicity we'll assume that our AI

# always plays as X.

#

# "X" for Xpert!

# "O" for Opponent!

#

# `board` is a 2-D grid of the state to be scored

# `current_player` is the player whose turn it is

# ('X' or 'O')

def minimax_score(board, current_player):

# If `board` is a terminal state, immediately

# return the appropriate score.

if x_has_won

return +10

else if o_has_won

return -10

else if is_draw

return 0

# If `board` is not a terminal state, get all

# moves that could be played.

legal_moves = get_legal_moves(board)

# Iterate through these moves, calculating a score

# for them and adding it to the `scores` array.

scores = []

for each move in legal_moves:

# First make the move

new_board = make_move(board, move, current_player)

# Then get the minimax score for the resulting

# state, passing in `current_player`'s opponents

# because it's their turn now.

#

# You may notice that `minimax_score` is calling itself -

# this is known as "recursion".

opponent = get_opponent(current_player)

score = minimax_score(new_board, opponent)

scores << score

# If `current_player` is X (our AI), then they are

# trying to maximize the score, so we should return

# the maximum of all the scores that we calculated.

if current_player == 'X'

return max(scores)

# If `current_player` is O (our AI's opponent), then

# they are trying to minimize the score. We should

# return the minimum.

else

return min(scores)

Here’s another description of the minimax_score function, this time structured as bullet-points:

- If X has won, immediately return +10

- If O has won, immediately return -10

- If the state is a draw, immediately return 0

- For each possible move for the current player, get the state that would result if that move was made

- For each of these states, use the

minimax_scorefunction to calculate its score. This is an example of “recursion” - a function calling itself. Store all of these scores in an array - If X is the current player, return the max of the scores resulting from each possible move (maximin-ing)

- If O is the current player, return the min of the scores (minimax-ing)

These descriptions of the minimax algorithm take a slightly different perspective to that of the previous section. In the previous section we began our analysis from terminal states, at the bottom of the tree. We then climbed up the tree using minimax, propagating scores up as we went.

However, our AI has to start its calculations from the early-game state it is given, which may be a long way from the terminal states on the leaves. Because of this, it structures its work in 2 “phases”.

Phase 1 is the unrolling of the recursion; the building of the tree. Each call to minimax_score in our pseudo-code begets several more calls to minimax_score, each of which begets several more calls, each of which… None of these calls return until they hit a terminal state that triggers one of the 3 if-branches at the top of the function. Hitting one of these branches allows minimax_score to immediately return -10, 0 or +10, without needing to make any further recursive calls to itself.

Phase 2 is the recursion rolling back up, once the tree has reached the terminal states that populate its leaves. This is the phase that we looked at in most depth in the previous section. As massively-nested calls to minimax_score start to return, the calls that spawned them can return too, and so on and so on back up the stack, until the original call returns a single number.

In the pseudo-code above, the 2 phases are actually interleaved with each other. If you trace the program through step-by-step, you’ll find that some calls to minimax_score start to return before others have even been made. The tree is constantly being both rolled and unrolled. However, the phase-based model is still valid and useful for understanding the algorithm. It would be completely possible to refactor our code to more sharply divide the phases; in fact, we’ll look at how to do this in the extensions section. As always, both approaches have their advantages and disadvantages.

It’s time to act

Write a perfect tic-tac-toe AI called minimax_ai. Re-read this section if and inevitably when you need to refresh some of the details. Google “minimax” and “tic-tac-toe minimax” and read other takes on the algorithm. My example code is there if you get truly stuck.

Tic-Tac-Toe is a simple game, but playing through every single possible game is still a lot of work, even for a modern, powerful computer. It can take over 10-20s for minimax to decide on a move at the very start of the game. In the extensions section, we’ll look at how to use caching to speed up the execution of our program by approximately 10x. To save yourself some time in the meantime, start by testing your AI using late game states. In particular, test with late game states where there are some moves that are clearly bad and some that are clearly good. Make sure that your AI only ever chooses the good ones.

There are several ways you can build confidence that your AI really is perfect.

- Play against it. Try to beat it, try to let it beat you.

- Battle 2 perfect AIs against each other. Since Tic-Tac-Toe is a draw with perfect play, every game they play should be drawn

- Battle a perfect AI against a worse AI. The perfect AI should never lose, and should sometimes win

- Write “unit tests” that assert that your AI makes the best move (or avoids the worst move) in a range of tricky states

Once you’re convinced that your AI is perfect, show it off to your family, friends and enemies. Especially your enemies. Once they see your power they won’t mess with you ever again.

Final task - say hi!

If you’ve successfully made it this far then I’d love to know! I’m going to be making more advanced-beginner projects like this, and I’d like to understand how to make them as useful as possible. Please send me an email to tell me about your achievement, I’d love to hear from you. You can also sign up for my mailing list at the bottom of this page to find out when I publish more advanced-beginner projects. I’m planning on writing at least 1 per month.

Once you’ve sent me that quick message, it’s time to move on to the extensions. They are even harder than the rest of the project, and come with even fewer pointers. Don’t be afraid to spend a lot of time just thinking and sketching out brief, experimental snatches of code.

Subscribe to my new "Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners" newsletter to receive concise weekly emails containing specific, real-world ways to make your code cleaner and more professional.

Each week I review code sent to me by one of my readers. I highlight the things that I like, discuss the things that I think could be better, and offer suggestions for how the author could make their code cleaner and easier to work with.

Subscribe now to receive these invaluable improvements in your inbox every week, completely free.

Extensions

Extension 1. Make our AI streetwise

Our AI chooses its moves based on the assumption that its opponent will play perfectly. This is sensible. Assuming the worst and respecting your opponent will win you many wars, both on and off the Tic-Tac-Toe board.

However, this mindset means that our AI doesn’t even consider the possibility that its opponent might make a mistake. It doesn’t bother trying to find tricksy moves that require precise play to defend against. As far as it’s concerned, its opponent’s play will always be precise, so what’s the point?