PFAB#3: How to rigorously analyze your journey to work

07 Dec 2019

Welcome to week 3 of Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners. In this series I review a program sent to me by one of my readers. I analyze their code, highlight the things that I like, and discuss the things that I think could be better. Most of all, I suggest small and big changes that the author could make in order to take their code to the next level.

(To receive all future PFABs as soon as they’re published, subscribe by email or follow me on Twitter. For the chance to have your code analyzed and featured in future a PFAB, go here)

This week’s program was sent to me by Michael Troyer, an archaeologist with an unexpectedly keen interest in computer programming. He prefers not to be called a code-slinging dinosaur hunter, but we all have to make compromises sometimes. Here’s how Michael describes his program:

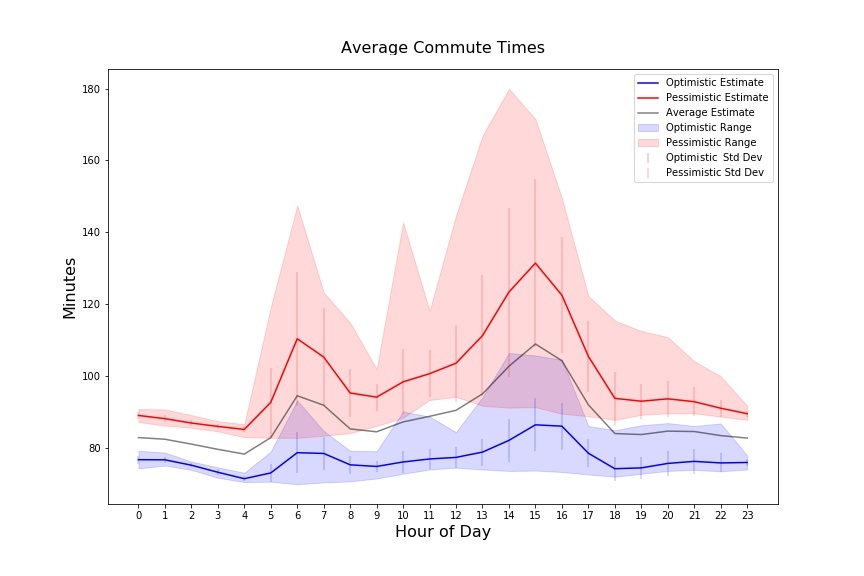

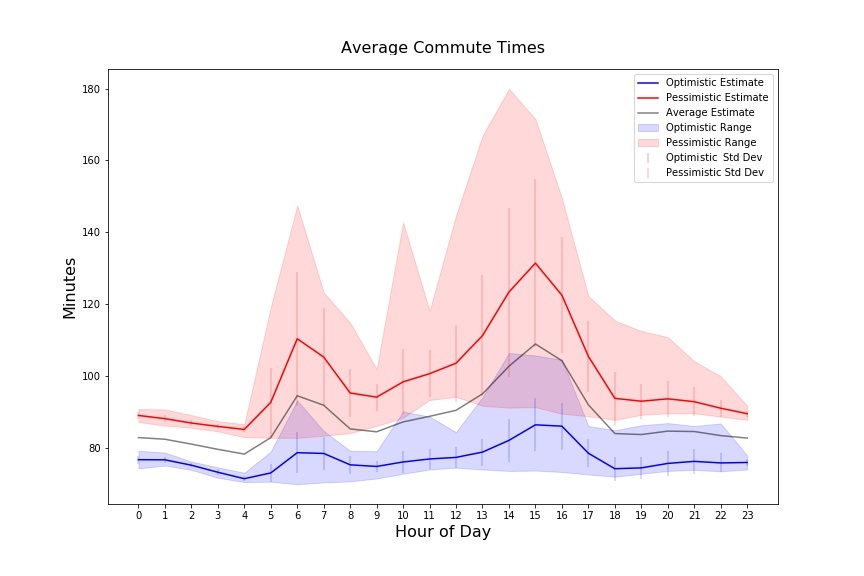

I was recently considering a new job in another city and was trying to decide if it was commutable or not. I was skeptical of most estimates as they didn’t really seem to consider real-time events like accidents (which are pretty regular on the route I was considering). So, I decided to use a scheduled script to regularly query the Google Maps API to get current commute time data and store it in a database, and then use this data to plot commute time average, min, max, standard deviation, etc. in order to get a more realistic assessment of an actual commute.

The tool worked well - and even convinced me to not take the new position. Using the basic Google Maps directions API to plot a hypothetical future commute (the departure time and/or arrival time parameters) typically indicated about a 60-70 minute one-way commute, which would be just barely within the realm of reason. However, I set my tool to ping the Google Maps API every thirty minutes and ran it for about a month, pulling live, real-time data throughout the day. Its results showed that the commute was more like 90-110 minutes each way on average for my anticipated travel windows; uhh no thanks, hard pass!

Instant full marks for imagination and execution, and the code is solid too. Before reading on, take a quick look at the code on GitHub. It’s written in Python, but uses very few Python-specific constructs and so should be quite understandable even if you haven’t used Python before.

Over the coming weeks we’ll look at how it could be made even better, but I’d like to start by talking about the aspects of the program that I particularly like.

1. The program is broken up into discrete components

The first thing I like about Michael’s code is the way it is structured. We talk a lot in PFAB about splitting code up into components that don’t care about each other’s internal logic, and this program is already very tidily chopped up.

Michael has split up his code into neat, separate components that:

- Query Google Maps

- Write data to a database (see below)

- Orchestrate the data retrieval and storage process

- Orchestrate the data analysis process

The components depend on each other like this:

+----------+ +-------------+

|run_app.py| |run_report.py|

+----+---+-+ +------+------+

| | |

| +-------------+ |

v v v

+------------------+ +-------------------+

|commute_handler.py| |database_handler.py|

+------------------+ +-------------------+

This split-up structure gives us all the benefits that we’ve talked about at length in previous PFABs. For example commute_handler.py doesn’t have to know anything about how database_handler.py works. And so long as commute_handler.py returns its commute data in a consistent format, database_handler.py doesn’t have to know anything about where it came from. These isolations make understanding and updating the code much simpler.

2. Using a database

The second thing I like about Michael’s code is his strategic use of a database to store his commute data. Every time he retrieves some new data from the Google Maps API, he immediately stashes it in a database. In abbreviated pseudo-code, this logic is:

while True:

commute = get_commute_data()

write_to_database(commute)

sleep(30 * 60)

# (data analysis performed by reading data from the

# database in a separate script)

For Michael’s use-case, this is a great idea. Technically, he could have got away without bothering with a database. He could have appended each new row of data to a normal list variable and then analyzed all of his data once he had collected enough of it. In pseudo-code this would have been:

all_commutes = []

for i in range(0, 10000):

commute = get_commute_data()

all_commutes.append(commute)

sleep(30 * 60)

print(analyze_commutes(all_commutes))

Stop reading and think for a second - why do you think Michael chose to store his data in a database?

I think he chose this approach because he wanted to be able to leave his script running for a long time in order to collect a lot of data. If he had gone with the second, in-memory approach, then if his program had stopped for any reason (a bug, computer turning off, power cut, etc) then he would have lost all of the data he had retrieved over the previous days.

But by writing to a database, Michael ensured that he immediately captured his data in a durable form. If his power had gone out after 2 weeks of patient data-collection then he would at least still have all the results that he had gathered up until that point. He could either perform his analysis using just the numbers that he had amassed so far, or restart the script and combine his new and old data later.

There’s no single rule that dictates whether you should write your program’s data to a database or keep it in-memory. Writing to a database is safer, but it isn’t free, and comes at the price of making your program slower and more complex. In general, the longer your data takes to reproduce, and the more you are interested in keeping it for future re-analysis, the more likely you should be to write to a database as you go.

In conclusion

I love the idea behind Michael’s program, and there’s a lot to admire about his code as well. Next week we’ll look at some ways that he could kick his already solid code up another notch or two.

In the meantime:

- To receive all future PFABs as soon as they’re published, subscribe to the mailing list

- Explore the archives: How Tinder keeps your exact location (a bit) private

- If you’ve written some code that you’d like feedback on, send it to me!

- Was any of this post unclear? Email or Tweet at me with suggestions, comments, and feedback on my feedback. I’d love to hear from you.

Welcome to week 3 of Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners. In this series I review a program sent to me by one of my readers. I analyze their code, highlight the things that I like, and discuss the things that I think could be better. Most of all, I suggest small and big changes that the author could make in order to take their code to the next level.

(To receive all future PFABs as soon as they’re published, subscribe by email or follow me on Twitter. For the chance to have your code analyzed and featured in future a PFAB, go here)

This week’s program was sent to me by Michael Troyer, an archaeologist with an unexpectedly keen interest in computer programming. He prefers not to be called a code-slinging dinosaur hunter, but we all have to make compromises sometimes. Here’s how Michael describes his program:

I was recently considering a new job in another city and was trying to decide if it was commutable or not. I was skeptical of most estimates as they didn’t really seem to consider real-time events like accidents (which are pretty regular on the route I was considering). So, I decided to use a scheduled script to regularly query the Google Maps API to get current commute time data and store it in a database, and then use this data to plot commute time average, min, max, standard deviation, etc. in order to get a more realistic assessment of an actual commute.

The tool worked well - and even convinced me to not take the new position. Using the basic Google Maps directions API to plot a hypothetical future commute (the departure time and/or arrival time parameters) typically indicated about a 60-70 minute one-way commute, which would be just barely within the realm of reason. However, I set my tool to ping the Google Maps API every thirty minutes and ran it for about a month, pulling live, real-time data throughout the day. Its results showed that the commute was more like 90-110 minutes each way on average for my anticipated travel windows; uhh no thanks, hard pass!

Instant full marks for imagination and execution, and the code is solid too. Before reading on, take a quick look at the code on GitHub. It’s written in Python, but uses very few Python-specific constructs and so should be quite understandable even if you haven’t used Python before.

Over the coming weeks we’ll look at how it could be made even better, but I’d like to start by talking about the aspects of the program that I particularly like.

1. The program is broken up into discrete components

The first thing I like about Michael’s code is the way it is structured. We talk a lot in PFAB about splitting code up into components that don’t care about each other’s internal logic, and this program is already very tidily chopped up.

Michael has split up his code into neat, separate components that:

- Query Google Maps

- Write data to a database (see below)

- Orchestrate the data retrieval and storage process

- Orchestrate the data analysis process

The components depend on each other like this:

+----------+ +-------------+

|run_app.py| |run_report.py|

+----+---+-+ +------+------+

| | |

| +-------------+ |

v v v

+------------------+ +-------------------+

|commute_handler.py| |database_handler.py|

+------------------+ +-------------------+

This split-up structure gives us all the benefits that we’ve talked about at length in previous PFABs. For example commute_handler.py doesn’t have to know anything about how database_handler.py works. And so long as commute_handler.py returns its commute data in a consistent format, database_handler.py doesn’t have to know anything about where it came from. These isolations make understanding and updating the code much simpler.

2. Using a database

The second thing I like about Michael’s code is his strategic use of a database to store his commute data. Every time he retrieves some new data from the Google Maps API, he immediately stashes it in a database. In abbreviated pseudo-code, this logic is:

while True:

commute = get_commute_data()

write_to_database(commute)

sleep(30 * 60)

# (data analysis performed by reading data from the

# database in a separate script)

For Michael’s use-case, this is a great idea. Technically, he could have got away without bothering with a database. He could have appended each new row of data to a normal list variable and then analyzed all of his data once he had collected enough of it. In pseudo-code this would have been:

all_commutes = []

for i in range(0, 10000):

commute = get_commute_data()

all_commutes.append(commute)

sleep(30 * 60)

print(analyze_commutes(all_commutes))

Stop reading and think for a second - why do you think Michael chose to store his data in a database?

I think he chose this approach because he wanted to be able to leave his script running for a long time in order to collect a lot of data. If he had gone with the second, in-memory approach, then if his program had stopped for any reason (a bug, computer turning off, power cut, etc) then he would have lost all of the data he had retrieved over the previous days.

But by writing to a database, Michael ensured that he immediately captured his data in a durable form. If his power had gone out after 2 weeks of patient data-collection then he would at least still have all the results that he had gathered up until that point. He could either perform his analysis using just the numbers that he had amassed so far, or restart the script and combine his new and old data later.

There’s no single rule that dictates whether you should write your program’s data to a database or keep it in-memory. Writing to a database is safer, but it isn’t free, and comes at the price of making your program slower and more complex. In general, the longer your data takes to reproduce, and the more you are interested in keeping it for future re-analysis, the more likely you should be to write to a database as you go.

In conclusion

I love the idea behind Michael’s program, and there’s a lot to admire about his code as well. Next week we’ll look at some ways that he could kick his already solid code up another notch or two.

In the meantime:

- To receive all future PFABs as soon as they’re published, subscribe to the mailing list

- Explore the archives: How Tinder keeps your exact location (a bit) private

- If you’ve written some code that you’d like feedback on, send it to me!

- Was any of this post unclear? Email or Tweet at me with suggestions, comments, and feedback on my feedback. I’d love to hear from you.