PFAB#5: How to make your programs shorter

21 Dec 2019

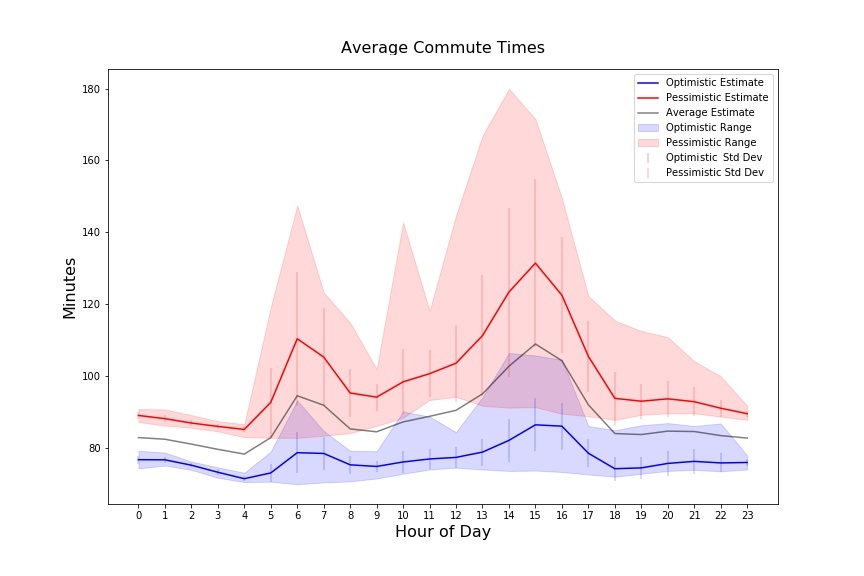

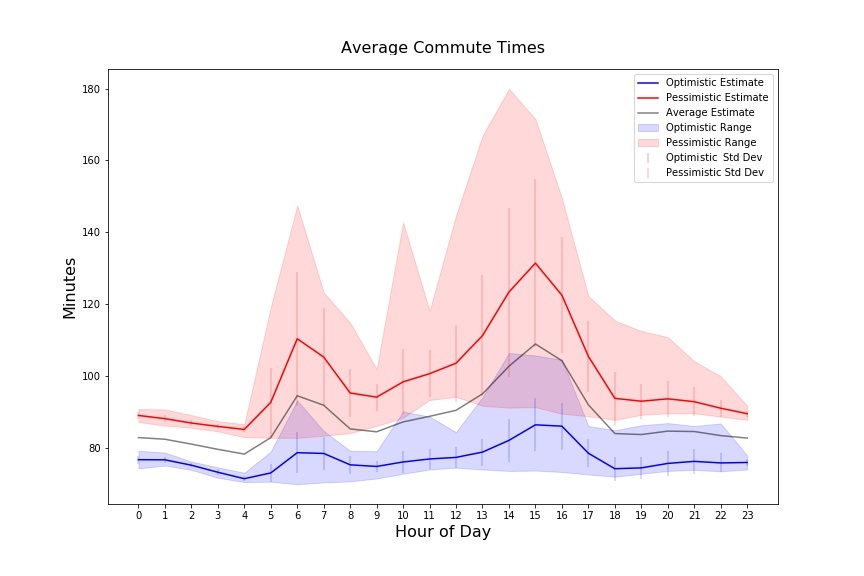

For the last two weeks we’ve been analyzing a program, written by an archaeologist named Michael Troyer, that measures commute times. So far we’ve admired the way in which its logic is split up, and have talked about how its error handling could be improved. In this final discussion of the program we’ll look at how we can tidy up and significantly shorten the code that handles querying its database.

Shorter programs aren’t always better. Sometimes it’s pragmatic to be verbose today in order to make your code more understandable tomorrow. But if you can make your code shorter and more readable at the same time then you’ve got a recipe for a cake plus eating it type of situation.

(You may want to open the code in GitHub to reference while you read this post.)

Simplifying the database code

Quick recap - Michael’s program has two commands. The first repeatedly queries the Google Maps API for the current commute time between two locations, and writes the results to a database. The second command reads the results back out of the database and calculates their average, range, and standard deviation.

Today we’re going to work on a function on Michael’s Database class called get_data. get_data is responsible for retrieving information about commute times from the program’s database, so that the program’s second command can analyze it. The function accepts arguments like specific_route, start_date and end_date, and uses these to filter down the data that it returns. Inside the function it constructs a SQL query using the arguments it receives, runs the query against the database, and returns the results.

You don’t need to know anything about the details of SQL in order to understand the get_data function, but here’s an example of a SQL query constructed by get_data:

SELECT *

FROM CommuteTimes

WHERE

Datetime > '2019-11-11' AND

Origin = "3180 18th Street, San Francisco" AND

Destination = "610 Townsend Street, San Francisco"

And here’s the get_data function as it is written today. It’s perfectly correct and functioning, but it’s also an 80-line monster. Have a read of it. Before reading further, see if you can identify any unnecessarily verbose sections. Then see if you can rewrite it in a much pithier form. As we’ll see, I was able to get it down to around 23 lines, making it more readable in the process.

class Database:

def get_data(self, start_date=None, end_date=None, specific_route=None):

"""

Return data from database between start_date and end_date.

Optionally allow a specific route: (origin, destination)

tuple.

Returns a pandas dataframe.

"""

if specific_route:

origin, destination = specific_route

try:

with sqlite3.connect(self.db_path) as con:

if specific_route:

if start_date:

if end_date:

# Start date and end date and specific route

query = "\

SELECT * FROM CommuteTimes \

WHERE (\

Datetime > ? AND \

Datetime < ? AND \

Origin = ? AND \

Destination = ? \

)"

params = (start_date, end_date, origin, destination,)

else:

# Start date only and specific route

query = "\

SELECT * FROM CommuteTimes \

WHERE (\

Datetime > ? AND \

Origin = ? AND \

Destination = ? \

)"

params = (start_date, origin, destination,)

elif end_date:

# End date only and specific route

query = "\

SELECT * FROM CommuteTimes \

WHERE (\

Datetime < ? AND \

Origin = ? AND \

Destination = ? \

)"

params=(end_date, origin, destination,)

else:

# No start or end date but specific route

query = "\

SELECT * FROM CommuteTimes \

WHERE (\

Origin = ? AND \

Destination = ? \

)"

params = (origin, destination,)

else:

if start_date:

if end_date:

# Start date and end date

query = "SELECT * FROM CommuteTimes WHERE (Datetime > ? AND Datetime < ?)"

params = (start_date, end_date,)

else:

# Start date only

query = "SELECT * FROM CommuteTimes WHERE Datetime > ?"

params = (start_date,)

elif end_date:

# End date only

query = "SELECT * FROM CommuteTimes WHERE Datetime < ?"

params = (end_date,)

else:

# No start or end date

query = "SELECT * FROM CommuteTimes"

params = None

# EDITOR'S NOTE: don't worry about exacty how `pd.read_sql_query`

# works. It's job is to query the database and format the results,

# but the details of how and why aren't important.

return pd.read_sql_query(query, con=con, parse_dates=['Datetime'], params=params)

except Exception as e:

print('Error getting data from database:', e)

How I would improve get_data

To improve get_data, I would first get rid of the try/except block entirely, for all the reasons discussed in our previous episode. If get_data throws an exception, it shouldn’t try to hide this fact by swallowing it. Instead, it should allow the code that called it to decide how to respond.

Second, I would try to reduce the repeated repetitive repetition throughout the function. When I read get_data for the first time, I immediately noticed that the string SELECT * From CommuteTimes was repeated 8 times. I also noticed that we have multiply-nested if-statements for every possible combination of the function’s arguments. For example, the function starts with the 3 blocks: if specific_route => if start_date => if end_date. This prol-IF-eration (sorry) is the root cause of the code’s already extreme repetitiousness. What’s more, suppose that we wanted to add another filter variable into our SQL query (such as time_of_day). We would need to add a fourth level of if-nesting to every block in our already precarious E-IF-fel Tower (sorry again). This would double the number of if-branches, to 16. This is madness.

After I got to the end of the function I didn’t immediately have a plan for how to tighten it up, but I knew that if I couldn’t then we were all doomed. I pondered a while. Then I noticed that none of the variables in the different if-branches depend on each other. By this I mean that the effect of an if start_date block is always to simply add a Datetime > ? condition to the WHERE clause of the SQL statement. It doesn’t matter whether end_date or specific_route is set. This means that we can examine every argument in its own, simple, un-nested if-statement. We can use these statements to build up a list of the different WHERE filters that we need to apply, and then construct the SQL query dynamically at the end of the function.

Here’s what I mean:

class Database:

def get_data(self, start_date=None, end_date=None, specific_route=None):

"""

Return data from database between start_date and end_date.

Optionally allow a specific route: (origin, destination)

tuple.

Returns a pandas dataframe.

"""

if specific_route:

origin, destination = specific_route

filters = []

if specific_route:

filters.append(("Origin = ?", origin))

filters.append(("Destination = ?", destination))

if start_date:

filters.append(("Datetime > ?", start_date))

if end_date:

filters.append(("Datetime < ?", end_date))

query = "SELECT * FROM CommuteTimes"

if len(filters) > 0:

# [f[0] for f in filters] is a Python "list

# comprehension". It is shorthand for:

#

# l = []

# for f in filters:

# l.append(f[0])

#

# Here we use a list comprehension to

# extract the first elements of the filter

# pairs we just created, and use them to

# construct our query.

clauses = [f[0] for f in filters]

query += " WHERE " + " AND ".join(clauses)

with sqlite3.connect(self.db_path) as con:

return pd.read_sql_query(query, con=con, parse_dates=['Datetime'], params=[f[1] for f in filters])

Now if we want to add a time_of_day parameter, we no longer have to add 8 new if-statement branches. Instead, we can add a single extra 2 line if-statement and call it a day:

if time_of_day:

filters.append(("TimeOfDay = ?", time_of_day))

That’s it. The pre-existing query-building code will magically take care of integrating the new filter into the query.

Conclusion

In order to apply this kind of reasoning to your own code, start by developing your sense of smell. Almost every day I write code that feels somehow off but that I don’t know how to improve. I usually finish up my attempt to the best of my ability, and then ask a co-worker for their opinion and advice. Sometimes they have some ideas, sometimes they don’t.

Developing a sense for when a piece of code can be improved is an important skill in itself, even when you aren’t immediately sure what to do about it. As you expand your toolbox of tricks and patterns, you’ll start to be able to fix more of the problems that you notice. Then you’ll start noticing more problems, then you’ll be able to fix them, then you’ll notice more problems, then… You’ll never be perfect or satisfied, but you will hopefully get paid more.

Until next week:

- To receive all future PFABs as soon as they’re published, subscribe to the mailing list

- Check out my series of Programming Projects for Advanced Beginners

- Explore the archives: I was 7 words away from being spear-phished

- If you’ve written some code that you’d like feedback on, send it to me!

- Was any of this post unclear? Email or Tweet at me with suggestions, comments, and feedback on my feedback. I’d love to hear from you.

For the last two weeks we’ve been analyzing a program, written by an archaeologist named Michael Troyer, that measures commute times. So far we’ve admired the way in which its logic is split up, and have talked about how its error handling could be improved. In this final discussion of the program we’ll look at how we can tidy up and significantly shorten the code that handles querying its database.

Shorter programs aren’t always better. Sometimes it’s pragmatic to be verbose today in order to make your code more understandable tomorrow. But if you can make your code shorter and more readable at the same time then you’ve got a recipe for a cake plus eating it type of situation.

(You may want to open the code in GitHub to reference while you read this post.)

Simplifying the database code

Quick recap - Michael’s program has two commands. The first repeatedly queries the Google Maps API for the current commute time between two locations, and writes the results to a database. The second command reads the results back out of the database and calculates their average, range, and standard deviation.

Today we’re going to work on a function on Michael’s Database class called get_data. get_data is responsible for retrieving information about commute times from the program’s database, so that the program’s second command can analyze it. The function accepts arguments like specific_route, start_date and end_date, and uses these to filter down the data that it returns. Inside the function it constructs a SQL query using the arguments it receives, runs the query against the database, and returns the results.

You don’t need to know anything about the details of SQL in order to understand the get_data function, but here’s an example of a SQL query constructed by get_data:

SELECT *

FROM CommuteTimes

WHERE

Datetime > '2019-11-11' AND

Origin = "3180 18th Street, San Francisco" AND

Destination = "610 Townsend Street, San Francisco"

And here’s the get_data function as it is written today. It’s perfectly correct and functioning, but it’s also an 80-line monster. Have a read of it. Before reading further, see if you can identify any unnecessarily verbose sections. Then see if you can rewrite it in a much pithier form. As we’ll see, I was able to get it down to around 23 lines, making it more readable in the process.

class Database:

def get_data(self, start_date=None, end_date=None, specific_route=None):

"""

Return data from database between start_date and end_date.

Optionally allow a specific route: (origin, destination)

tuple.

Returns a pandas dataframe.

"""

if specific_route:

origin, destination = specific_route

try:

with sqlite3.connect(self.db_path) as con:

if specific_route:

if start_date:

if end_date:

# Start date and end date and specific route

query = "\

SELECT * FROM CommuteTimes \

WHERE (\

Datetime > ? AND \

Datetime < ? AND \

Origin = ? AND \

Destination = ? \

)"

params = (start_date, end_date, origin, destination,)

else:

# Start date only and specific route

query = "\

SELECT * FROM CommuteTimes \

WHERE (\

Datetime > ? AND \

Origin = ? AND \

Destination = ? \

)"

params = (start_date, origin, destination,)

elif end_date:

# End date only and specific route

query = "\

SELECT * FROM CommuteTimes \

WHERE (\

Datetime < ? AND \

Origin = ? AND \

Destination = ? \

)"

params=(end_date, origin, destination,)

else:

# No start or end date but specific route

query = "\

SELECT * FROM CommuteTimes \

WHERE (\

Origin = ? AND \

Destination = ? \

)"

params = (origin, destination,)

else:

if start_date:

if end_date:

# Start date and end date

query = "SELECT * FROM CommuteTimes WHERE (Datetime > ? AND Datetime < ?)"

params = (start_date, end_date,)

else:

# Start date only

query = "SELECT * FROM CommuteTimes WHERE Datetime > ?"

params = (start_date,)

elif end_date:

# End date only

query = "SELECT * FROM CommuteTimes WHERE Datetime < ?"

params = (end_date,)

else:

# No start or end date

query = "SELECT * FROM CommuteTimes"

params = None

# EDITOR'S NOTE: don't worry about exacty how `pd.read_sql_query`

# works. It's job is to query the database and format the results,

# but the details of how and why aren't important.

return pd.read_sql_query(query, con=con, parse_dates=['Datetime'], params=params)

except Exception as e:

print('Error getting data from database:', e)

How I would improve get_data

To improve get_data, I would first get rid of the try/except block entirely, for all the reasons discussed in our previous episode. If get_data throws an exception, it shouldn’t try to hide this fact by swallowing it. Instead, it should allow the code that called it to decide how to respond.

Second, I would try to reduce the repeated repetitive repetition throughout the function. When I read get_data for the first time, I immediately noticed that the string SELECT * From CommuteTimes was repeated 8 times. I also noticed that we have multiply-nested if-statements for every possible combination of the function’s arguments. For example, the function starts with the 3 blocks: if specific_route => if start_date => if end_date. This prol-IF-eration (sorry) is the root cause of the code’s already extreme repetitiousness. What’s more, suppose that we wanted to add another filter variable into our SQL query (such as time_of_day). We would need to add a fourth level of if-nesting to every block in our already precarious E-IF-fel Tower (sorry again). This would double the number of if-branches, to 16. This is madness.

After I got to the end of the function I didn’t immediately have a plan for how to tighten it up, but I knew that if I couldn’t then we were all doomed. I pondered a while. Then I noticed that none of the variables in the different if-branches depend on each other. By this I mean that the effect of an if start_date block is always to simply add a Datetime > ? condition to the WHERE clause of the SQL statement. It doesn’t matter whether end_date or specific_route is set. This means that we can examine every argument in its own, simple, un-nested if-statement. We can use these statements to build up a list of the different WHERE filters that we need to apply, and then construct the SQL query dynamically at the end of the function.

Here’s what I mean:

class Database:

def get_data(self, start_date=None, end_date=None, specific_route=None):

"""

Return data from database between start_date and end_date.

Optionally allow a specific route: (origin, destination)

tuple.

Returns a pandas dataframe.

"""

if specific_route:

origin, destination = specific_route

filters = []

if specific_route:

filters.append(("Origin = ?", origin))

filters.append(("Destination = ?", destination))

if start_date:

filters.append(("Datetime > ?", start_date))

if end_date:

filters.append(("Datetime < ?", end_date))

query = "SELECT * FROM CommuteTimes"

if len(filters) > 0:

# [f[0] for f in filters] is a Python "list

# comprehension". It is shorthand for:

#

# l = []

# for f in filters:

# l.append(f[0])

#

# Here we use a list comprehension to

# extract the first elements of the filter

# pairs we just created, and use them to

# construct our query.

clauses = [f[0] for f in filters]

query += " WHERE " + " AND ".join(clauses)

with sqlite3.connect(self.db_path) as con:

return pd.read_sql_query(query, con=con, parse_dates=['Datetime'], params=[f[1] for f in filters])

Now if we want to add a time_of_day parameter, we no longer have to add 8 new if-statement branches. Instead, we can add a single extra 2 line if-statement and call it a day:

if time_of_day:

filters.append(("TimeOfDay = ?", time_of_day))

That’s it. The pre-existing query-building code will magically take care of integrating the new filter into the query.

Conclusion

In order to apply this kind of reasoning to your own code, start by developing your sense of smell. Almost every day I write code that feels somehow off but that I don’t know how to improve. I usually finish up my attempt to the best of my ability, and then ask a co-worker for their opinion and advice. Sometimes they have some ideas, sometimes they don’t.

Developing a sense for when a piece of code can be improved is an important skill in itself, even when you aren’t immediately sure what to do about it. As you expand your toolbox of tricks and patterns, you’ll start to be able to fix more of the problems that you notice. Then you’ll start noticing more problems, then you’ll be able to fix them, then you’ll notice more problems, then… You’ll never be perfect or satisfied, but you will hopefully get paid more.

Until next week:

- To receive all future PFABs as soon as they’re published, subscribe to the mailing list

- Check out my series of Programming Projects for Advanced Beginners

- Explore the archives: I was 7 words away from being spear-phished

- If you’ve written some code that you’d like feedback on, send it to me!

- Was any of this post unclear? Email or Tweet at me with suggestions, comments, and feedback on my feedback. I’d love to hear from you.