PFAB #17: pre-computation sounds like cheating but isn't

27 Jun 2020

This post is part of “Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners”, a regular series that helps you make the leap from cobbling programs together to writing elegant, thoughtful code. Subscribe now to receive PFAB in your inbox, every fortnight, entirely free.

Last time on Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners we started speeding up Justin Reppert’s ASCII art generator. We looked at how to improve Justin’s algorithm for mapping image colors to terminal colors and devised an approach that got the job done thirty times faster. If you haven’t read last week’s PFAB then I’d suggest you start there. It’s not long and it got rave reviews.

A thirty-x speedup is nothing to sneeze at, but this week we’re going to optimize Justin’s program even further. What we’re about to do might feel like cheating, but it’s really just good practise.

Pre-computation

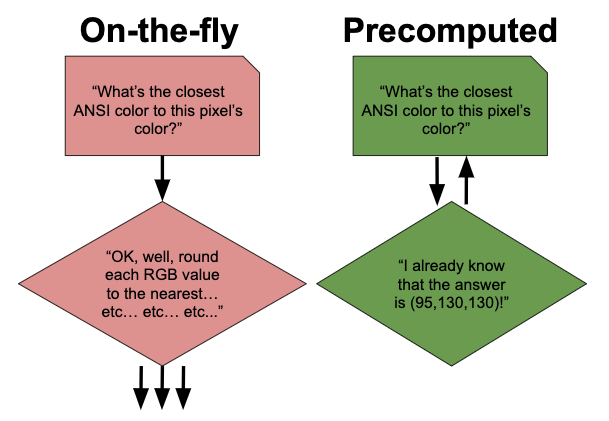

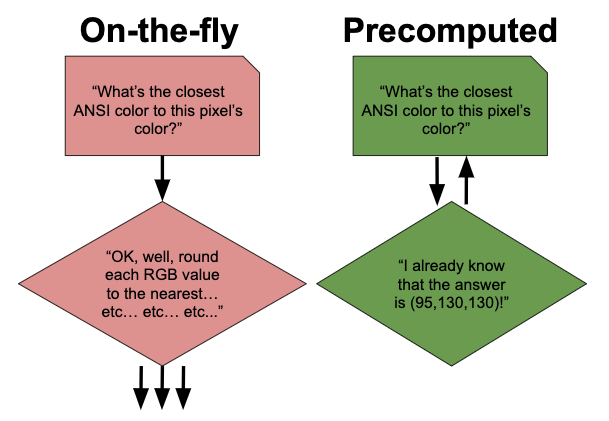

At the moment Justin’s program goes through each pixel in a source image and computes the closest ANSI color that can be displayed by his terminal. The program performs each calculation as it goes, on-the-fly. But what if we already knew all the answers? What if we had already worked out the closest ANSI color to every possible pixel color? Then our program wouldn’t need to do any computation; instead it could instantly look up the closest ANSI color to each pixel color in zero seconds flat.

“Well yes,” you might say, “if you know all the answers in advance then of course your algorithm will be faster. But there’s no such thing as a free lunch, and we still have to do all the work to find those answers at some point.

“In fact,” you might continue, “if we use this approach then the price of our lunch actually increases. If we use the on-the-fly method method for an 80x80 image then we have to calculate the closest ANSI color to a pixel color 80 * 80 = 6,400 times. But if we calculate in advance the closest ANSI color to every possible pixel color then we have to do 256 * 256 * 256 =~ 16,000,000 calculations, almost all of which will be wasted. This is like saying that producing Lord of the Rings was easy because all the publisher had to do was press print and a best-selling book came out.” If you were paying me for any of my blog posts, which you aren’t, you might ostentatiously demand a refund.

However, you’d be missing some important subtleties. What we think of as a program’s “speed” depends on the context. Programs are written to be used, and so arguably the most important definition of “speed” is the time that a program takes to respond to a user’s request. For our program, this is the time between a user asking for a colorful ASCII art image and our program printing this image to the terminal.

Pre-computing all the answers may require more total work to be performed. However, we can do all of the pre-computation in advance of the program being run. We can store the results in a file or a database, and load them when our program runs. This means that the user doesn’t have to sit and wait while we run all the calculations. They can benefit from our work without having to sit through it. There’s no free lunch, but like any good investment bank we can use some sleight of hand to palm the costs off onto someone else.

Is this actually a good idea?

The code for the pre-computation algorithm will be very simple: for each pixel, look up the correct answer in a pre-existing answer list. We also have to write a separate script to calculate all the answers ahead of time, but this is no harder than calculating the answer for each pixel on-the-fly, which is what we are currently doing. However, whether any of this is actually a good idea depends on the specifics of how Justin intends his program to be used and how we store our pre-computed color mapping.

Let’s start by discussing our storage options. Two of the simplest ways to store our pre-computed mapping are in a file using a serialization format like JSON, or in a database like SQLite.

JSON:

{

// Pixel color => closest ANSI color

"000000": "000000",

"000001": "000000",

"000002": "000000",

// etc...

}

SQLite:

| id | pixel | ansi |

+----+--------+--------+

| 1 | 000000 | 000000 |

| 2 | 000001 | 000000 |

| 3 | 000002 | 000000 |

As always, there are tradeoffs between these two options. I would expect the code that loads data from a JSON file to be simpler than the code that loads it from a database, because there are fewer moving parts. I would also expect it to be faster to retrieve a record from a JSON file (once it has been loaded and parsed) than from a database because retrieving data from Python dictionaries is a very speedy operation. Retrieving data from a database, especially one with 16MM rows, is typically slower than in-memory operations like retrieving data from a dictionary, although reading from a database can be sped up by using database indexes.

On the other hand, at the start of our program it will take much longer to load and parse a large JSON file than it will take to connect to a SQLite database. As part of implementing this algorithm (see below) I generated a JSON file containing all the pre-computated mappings from RGB values to the closest ANSI colors. It was 350MB in size. I think I could have used some tricks to slim it down (which we’ll talk about in a future PFAB), but not by very much. My computer took around 20 seconds to load and parse the file. For a single 80x80 image, this means that even though generating an image would take a fraction of the time of an on-the-fly approach, the overall program would still take substantially more time to run from start to finish.

How do we make these tradeoffs?

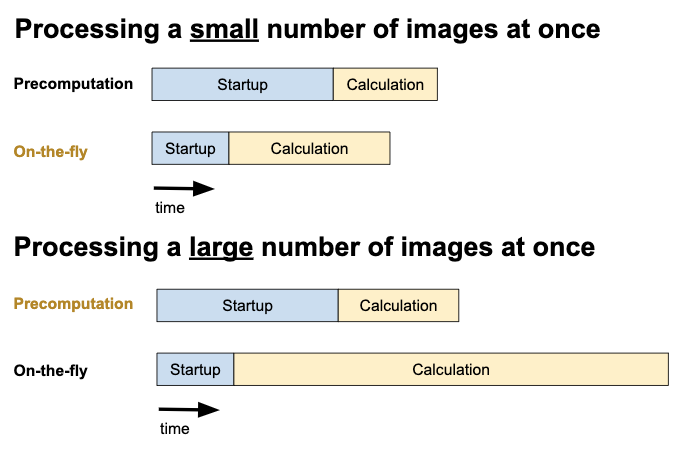

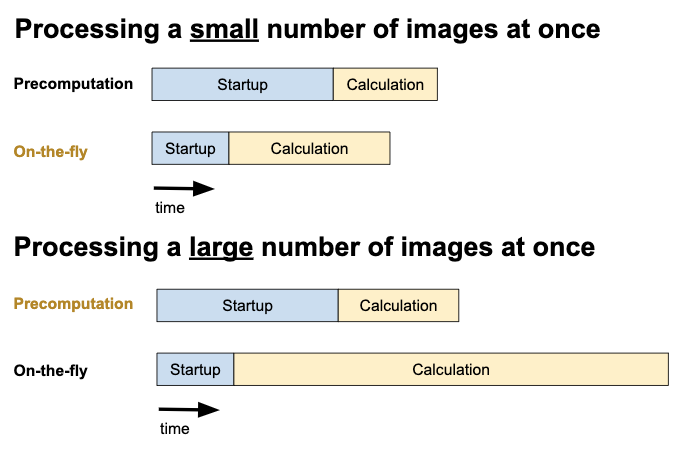

This long list of tradeoffs illustrates why the way in which Justin’s program is used is important. If the program is only intended to generate a single image at a time, then storing our pre-computed color map in a database will likely be the best solution. This is because it’s not worth spending the time to load a large JSON file if we’re only going to use it once. However, if the program is used to generate many images in a single run then we still only have to load the JSON file once. This means that accepting the large fixed cost of loading the JSON file starts to look like a good idea if it reduces our time to retrieve the color mapping for a pixel.

Let’s formalize this a little. The overall running time of our program can be approximated using the following equation:

total_time = startup_time + (time_per_image * n_images)

When n_images is small, total_time is dominated by the startup_time term. This means that to minimize total_time we need to focus on minimizing startup_time. This indicates that we should read our data from a database, or even stick with calculating it on-the-fly as in the previous PFAB.

However, as n_images gets large, the time_per_image * n_images term starts to dominate. Now to minimize total_time we need to focus on minimizing time_per_image, not startup_time. In other words, the more images we process, the more sensible it becomes to accept a large startup_time if in exchange we get a smaller time_per_image. This is exactly what pre-computing all the answers achieves, especially if we load our answers into memory from a JSON file instead of querying them from a database.

Using an approach with a small time_per_image also becomes more beneficial the larger each image is. This is because the more pixels we are processing, the more important it becomes to minimize the time we spend on each pixel. We can rewrite our previous equation in terms of pixels as follows:

total_time = startup_time + (time_per_pixel * pixels_per_image * n_images)

The larger pixels_per_image is, the larger the (time_per_pixel * pixels_per_image * n_images) term, and the more important it becomes to minimize time_per_pixel instead of startup_time.

Getting the best of all worlds

This analysis shows us that the fastest algorithm depends on the inputs our program receives. This means that if we really, really want to optimize our program’s performance (which after all is the whole point of this post) then we should change the algorithm that we used based on the inputs we receive.

We could run our program repeatedly and record how the different algorithms perform for different inputs. We could use this data to estimate how long each approach will take for a given input set of images. For example, if we are given 1000 images that are each 640x480 pixels in size, we might choose to accept the startup performance hit of loading the pre-computed color map in exchange for a minimal time-per-pixel. We have so many calculations to do that we will be able to efficiently amortize the startup cost over them all. By contrast, if we are given just 2 images of 80x80 pixels in size, we might decide that connecting to a database or even using an on-the-fly approach will be quicker. All of this calculation can be done transparently in the background, without the user having to know or care what we are doing.

Where’s the code?

I’ve updated Justin’s program to pre-compute color mappings and store them in a JSON file. You can read the full code here; see here for the most important changes. You can also read just the diff between the old and new versions here. Storing color mappings in a database and choosing an algorithm based on user inputs is left as an exercise for the reader.

Conclusion

At first glance, pre-computing the closest ANSI color to every single RGB value seems like a stupid, gluttonous idea. And in some situations it is. But what sounds stupid for a single image might not be so ridiculous for hundreds of images, and the more work your program is doing, the more work it’s worth you putting in to optimize it.

You’ll rarely need to write out equations in the same way as we did here, or to know off-hand how long it takes to access a dictionary or a database. But it does pay to build up your intuition about how different approaches behave at different scales. And if you need to cast-iron ensure that your program is as fast as it can possibly be then you can’t beat trying a few things out and timing them.

New to Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners? Catch up with the full archives, subscribe to future editions, and learn how to make your programs shorter, clearer, and easier for other people to work with.

This post is part of “Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners”, a regular series that helps you make the leap from cobbling programs together to writing elegant, thoughtful code. Subscribe now to receive PFAB in your inbox, every fortnight, entirely free.

Last time on Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners we started speeding up Justin Reppert’s ASCII art generator. We looked at how to improve Justin’s algorithm for mapping image colors to terminal colors and devised an approach that got the job done thirty times faster. If you haven’t read last week’s PFAB then I’d suggest you start there. It’s not long and it got rave reviews.

A thirty-x speedup is nothing to sneeze at, but this week we’re going to optimize Justin’s program even further. What we’re about to do might feel like cheating, but it’s really just good practise.

Pre-computation

At the moment Justin’s program goes through each pixel in a source image and computes the closest ANSI color that can be displayed by his terminal. The program performs each calculation as it goes, on-the-fly. But what if we already knew all the answers? What if we had already worked out the closest ANSI color to every possible pixel color? Then our program wouldn’t need to do any computation; instead it could instantly look up the closest ANSI color to each pixel color in zero seconds flat.

“Well yes,” you might say, “if you know all the answers in advance then of course your algorithm will be faster. But there’s no such thing as a free lunch, and we still have to do all the work to find those answers at some point.

“In fact,” you might continue, “if we use this approach then the price of our lunch actually increases. If we use the on-the-fly method method for an 80x80 image then we have to calculate the closest ANSI color to a pixel color 80 * 80 = 6,400 times. But if we calculate in advance the closest ANSI color to every possible pixel color then we have to do 256 * 256 * 256 =~ 16,000,000 calculations, almost all of which will be wasted. This is like saying that producing Lord of the Rings was easy because all the publisher had to do was press print and a best-selling book came out.” If you were paying me for any of my blog posts, which you aren’t, you might ostentatiously demand a refund.

However, you’d be missing some important subtleties. What we think of as a program’s “speed” depends on the context. Programs are written to be used, and so arguably the most important definition of “speed” is the time that a program takes to respond to a user’s request. For our program, this is the time between a user asking for a colorful ASCII art image and our program printing this image to the terminal.

Pre-computing all the answers may require more total work to be performed. However, we can do all of the pre-computation in advance of the program being run. We can store the results in a file or a database, and load them when our program runs. This means that the user doesn’t have to sit and wait while we run all the calculations. They can benefit from our work without having to sit through it. There’s no free lunch, but like any good investment bank we can use some sleight of hand to palm the costs off onto someone else.

Is this actually a good idea?

The code for the pre-computation algorithm will be very simple: for each pixel, look up the correct answer in a pre-existing answer list. We also have to write a separate script to calculate all the answers ahead of time, but this is no harder than calculating the answer for each pixel on-the-fly, which is what we are currently doing. However, whether any of this is actually a good idea depends on the specifics of how Justin intends his program to be used and how we store our pre-computed color mapping.

Let’s start by discussing our storage options. Two of the simplest ways to store our pre-computed mapping are in a file using a serialization format like JSON, or in a database like SQLite.

JSON:

{

// Pixel color => closest ANSI color

"000000": "000000",

"000001": "000000",

"000002": "000000",

// etc...

}

SQLite:

| id | pixel | ansi |

+----+--------+--------+

| 1 | 000000 | 000000 |

| 2 | 000001 | 000000 |

| 3 | 000002 | 000000 |

As always, there are tradeoffs between these two options. I would expect the code that loads data from a JSON file to be simpler than the code that loads it from a database, because there are fewer moving parts. I would also expect it to be faster to retrieve a record from a JSON file (once it has been loaded and parsed) than from a database because retrieving data from Python dictionaries is a very speedy operation. Retrieving data from a database, especially one with 16MM rows, is typically slower than in-memory operations like retrieving data from a dictionary, although reading from a database can be sped up by using database indexes.

On the other hand, at the start of our program it will take much longer to load and parse a large JSON file than it will take to connect to a SQLite database. As part of implementing this algorithm (see below) I generated a JSON file containing all the pre-computated mappings from RGB values to the closest ANSI colors. It was 350MB in size. I think I could have used some tricks to slim it down (which we’ll talk about in a future PFAB), but not by very much. My computer took around 20 seconds to load and parse the file. For a single 80x80 image, this means that even though generating an image would take a fraction of the time of an on-the-fly approach, the overall program would still take substantially more time to run from start to finish.

How do we make these tradeoffs?

This long list of tradeoffs illustrates why the way in which Justin’s program is used is important. If the program is only intended to generate a single image at a time, then storing our pre-computed color map in a database will likely be the best solution. This is because it’s not worth spending the time to load a large JSON file if we’re only going to use it once. However, if the program is used to generate many images in a single run then we still only have to load the JSON file once. This means that accepting the large fixed cost of loading the JSON file starts to look like a good idea if it reduces our time to retrieve the color mapping for a pixel.

Let’s formalize this a little. The overall running time of our program can be approximated using the following equation:

total_time = startup_time + (time_per_image * n_images)

When n_images is small, total_time is dominated by the startup_time term. This means that to minimize total_time we need to focus on minimizing startup_time. This indicates that we should read our data from a database, or even stick with calculating it on-the-fly as in the previous PFAB.

However, as n_images gets large, the time_per_image * n_images term starts to dominate. Now to minimize total_time we need to focus on minimizing time_per_image, not startup_time. In other words, the more images we process, the more sensible it becomes to accept a large startup_time if in exchange we get a smaller time_per_image. This is exactly what pre-computing all the answers achieves, especially if we load our answers into memory from a JSON file instead of querying them from a database.

Using an approach with a small time_per_image also becomes more beneficial the larger each image is. This is because the more pixels we are processing, the more important it becomes to minimize the time we spend on each pixel. We can rewrite our previous equation in terms of pixels as follows:

total_time = startup_time + (time_per_pixel * pixels_per_image * n_images)

The larger pixels_per_image is, the larger the (time_per_pixel * pixels_per_image * n_images) term, and the more important it becomes to minimize time_per_pixel instead of startup_time.

Getting the best of all worlds

This analysis shows us that the fastest algorithm depends on the inputs our program receives. This means that if we really, really want to optimize our program’s performance (which after all is the whole point of this post) then we should change the algorithm that we used based on the inputs we receive.

We could run our program repeatedly and record how the different algorithms perform for different inputs. We could use this data to estimate how long each approach will take for a given input set of images. For example, if we are given 1000 images that are each 640x480 pixels in size, we might choose to accept the startup performance hit of loading the pre-computed color map in exchange for a minimal time-per-pixel. We have so many calculations to do that we will be able to efficiently amortize the startup cost over them all. By contrast, if we are given just 2 images of 80x80 pixels in size, we might decide that connecting to a database or even using an on-the-fly approach will be quicker. All of this calculation can be done transparently in the background, without the user having to know or care what we are doing.

Where’s the code?

I’ve updated Justin’s program to pre-compute color mappings and store them in a JSON file. You can read the full code here; see here for the most important changes. You can also read just the diff between the old and new versions here. Storing color mappings in a database and choosing an algorithm based on user inputs is left as an exercise for the reader.

Conclusion

At first glance, pre-computing the closest ANSI color to every single RGB value seems like a stupid, gluttonous idea. And in some situations it is. But what sounds stupid for a single image might not be so ridiculous for hundreds of images, and the more work your program is doing, the more work it’s worth you putting in to optimize it.

You’ll rarely need to write out equations in the same way as we did here, or to know off-hand how long it takes to access a dictionary or a database. But it does pay to build up your intuition about how different approaches behave at different scales. And if you need to cast-iron ensure that your program is as fast as it can possibly be then you can’t beat trying a few things out and timing them.

New to Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners? Catch up with the full archives, subscribe to future editions, and learn how to make your programs shorter, clearer, and easier for other people to work with.