PFAB #11: Separating logic and data

07 Mar 2020

This post is part of my “Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners” series, which helps you make the leap from knowing how to cobble messy programs toether to writing clean, elegant code. Subscribe now to receive PFAB in your inbox, every fortnight, entirely free.

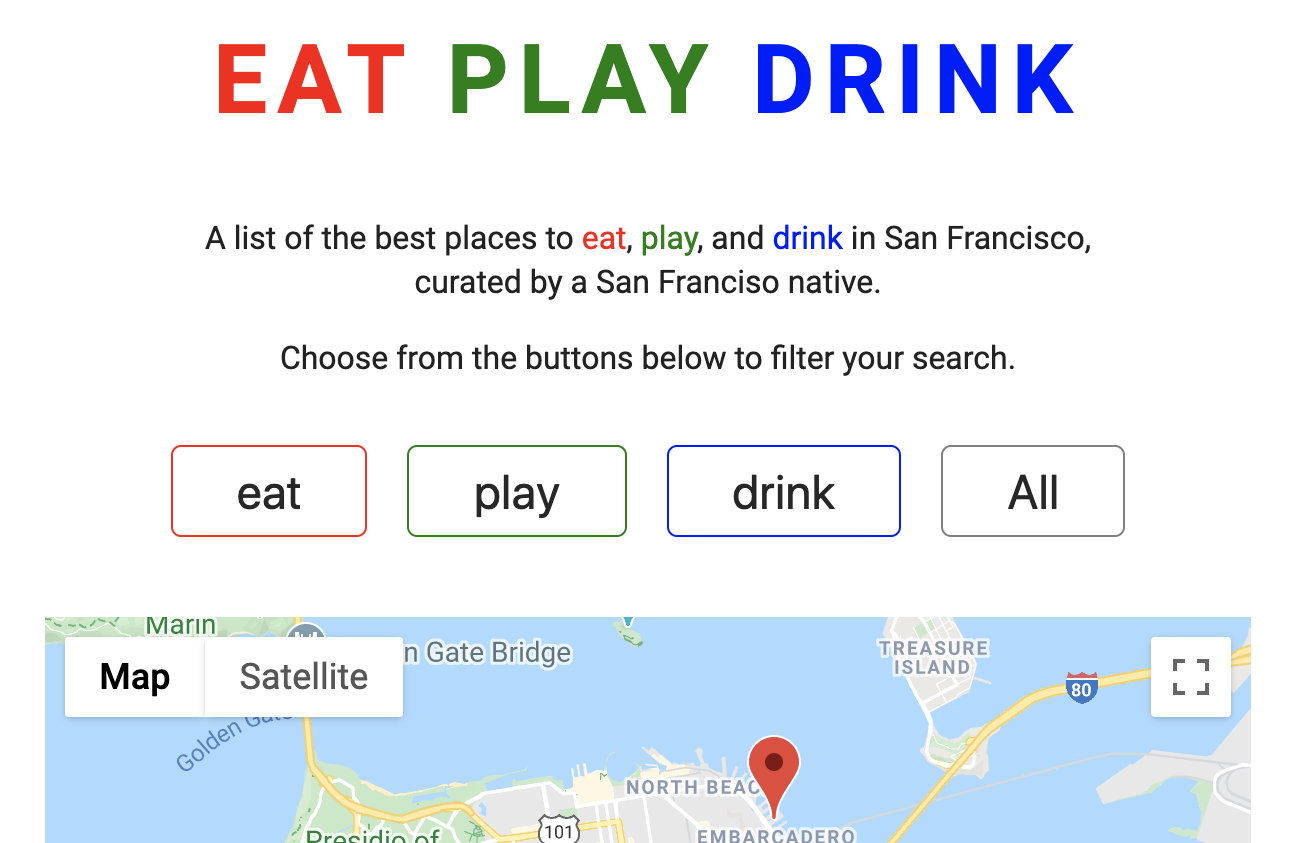

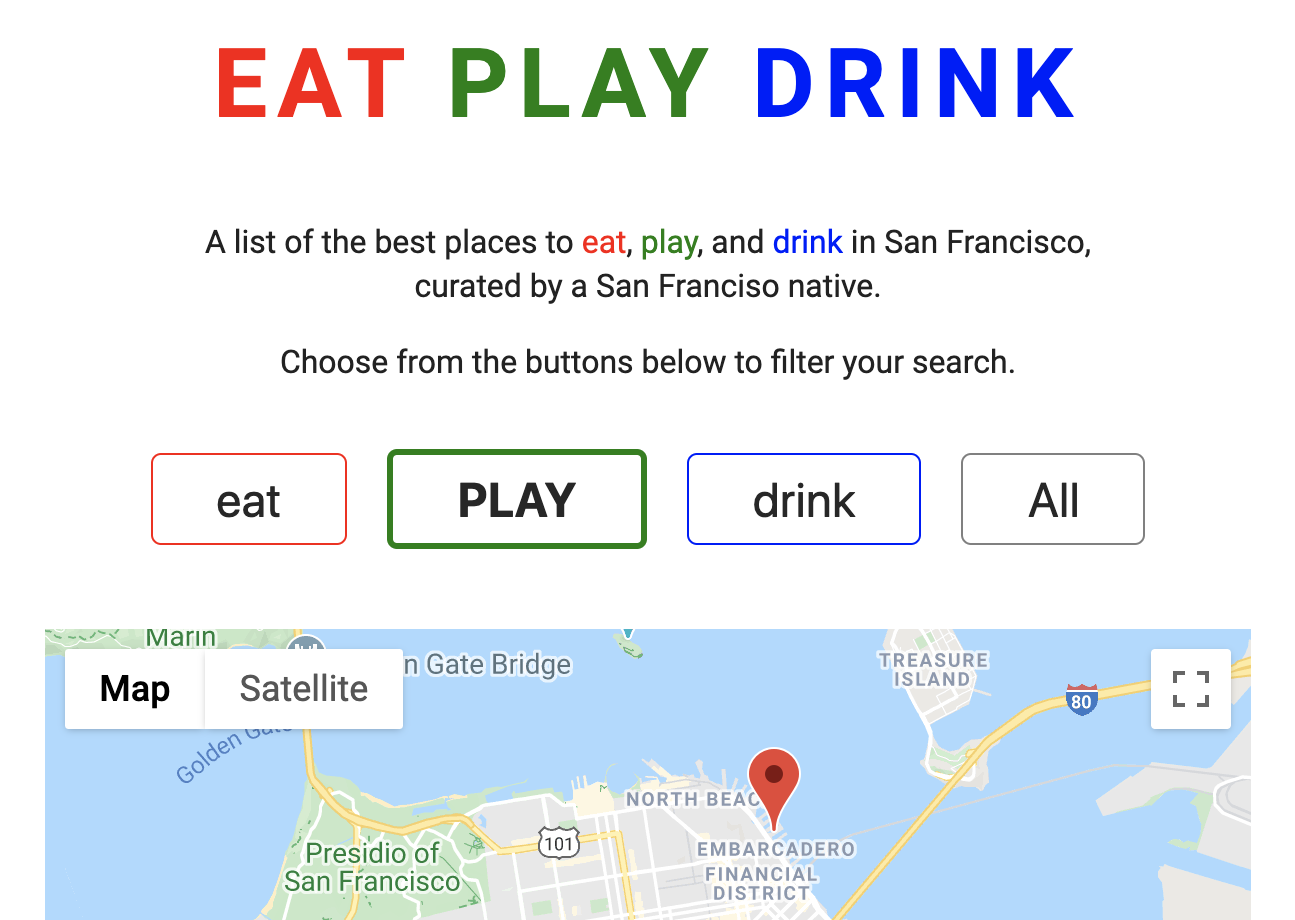

This week on Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners we’re going to start analyzing a brand new project. It’s an interactive website called Eat/Play/Drink, created by PFAB reader Sophia Li. Eat/Play/Drink presents the user with a curated map of places to eat, play, and drink, and allows the user to filter the map by category.

As with almost every program that we analyze in PFAB, Sophia’s program is already entirely functional and fit for purpose. You can even view it in action at https://sophiali.dev/eat-play-drink. The changes that we’re going to suggest would only start to become particularly important if the codebase grew larger or was being worked on by multiple programmers. For a small, personal side-project the changes should therefore be considered somewhat optional, but they’re still good opportunities for practice and learning.

Over the coming editions of PFAB we’re going to look at how Sophie could restructure her code so as to make it more “defensive”. This means anticipating the types of bugs that future programmers could accidentally introduce (Sophie-in-a-month counts as a future programmer!), and programming in a style that mitigates or prevents these bugs altogether.

But first I want to start our journey by discussing a design choice that Sophie made that I particularly like: enforcing the separation of logic and data.

Separating logic and data

Let’s start with a quick tour of the code (you can also read it in full on GitHub).

Eat/Play/Drink is built using HTML and JavaScript. If you aren’t familiar with these technologies then don’t worry - the concepts that we’re going to talk about are applicable to all other languages too. Roughly speaking, HTML is how you describe what a website looks like, and JavaScript is how you dynamically update it (for example, expanding a menu when a user clicks on a button).

HTML looks like this:

<!-- A simple website with an image and a button -->

<html>

<body>

<img id="main-pic" src="/images/photo-of-me.jpg" />

<button id="btn-change-pic" value="Change the pic!" />

</body>

</html>

JavaScript looks like this:

// When the user clicks on the button, change the image

$("#btn-change-pic").click(function() {

$("#main-pic").attr("src", "/images/photo-of-you.jpg");

});

The HTML for Eat/Play/Drink lives in a file called index.html ([view][index_html]). We’re not going to talk about this file much this week. The JavaScript lives in a file called app.js ([view][app_js]). It is responsible for creating Google Maps markers and “info boxes”, and for showing and hiding these components whenever a user clicks on a filter button.

At the top of app.js is an array called markers. This array contains details about each place on the Eat/Play/Drink map, including a place’s co-ordinates, category, and description:

const markers = [

{

coords: { lat: 37.7638, lng: -122.469 },

content:

"<h3>San Tung</h3><p>Chinese restaurant with delicious dry fried chicken wings.</p><a href='https://goo.gl/maps/wiqva8qzW9bBoJRJ6' target='_blank'>Get directions</a>",

category: "eat"

},

// ...etc...

}

I really like this array. It encapsulates all of the website’s data, keeping it completely isolated from the logic that is responsible for displaying it. This separation is valuable, for two reasons.

First, it’s almost always good to keep different components of your code separate from each other, regardless of what those components are. As we’ve talked about at length in previous PFABs, code that is well-separated into discrete components will, as a natural, inevitable consequence, tend to be easier to understand and work with.

Second, separating logic and data allows us to add new places to the Eat/Play/Drink app without needing to go anywhere near the code that is responsible for displaying those new places. Instead, we can add our new places to the markers array using a simple, well-defined format. We can hit save and refresh the page, and the new markers and info windows are immediately available to be clicked on.

As well as improving our lives in the short-term, separating logic and data opens up extra possibilities for the future too.

Future benefits of separating data and logic

We can make data updates even simpler

With only a little extra work, we could make it even easier for anyone to update our app’s code with new places, even if they aren’t a programmer. Non-programmers could probably already add a new element to the markers array in a pinch, but it might be intimidating to require them to edit a full JavaScript file that also contains functions, loops, if-statements, and so on. To alleviate this, we could move our places data to an entirely separate file (perhaps called places.json). This file would contain nothing but data, formatted as JSON. JSON stands for JavaScript Object Notation, and is a simple format for representing data. For example:

{

"places": [

{

"coords": { "lat": 37.7638, "lng": -122.469 },

"content":

"<h3>San Tung</h3><p>Chinese restaurant with delicious dry fried chicken wings.</p><a href='https://goo.gl/maps/wiqva8qzW9bBoJRJ6' target='_blank'>Get directions</a>",

"category": "eat"

}

// ...etc...

]

}

JSON files only represent data, and don’t contain any logic whatsoever. app.js would read and load the data from the JSON file, and then use it to perform all the presentation and other heavy lifting, just as it does today.

+-----------+ +------+ +----------+

|places.json+--->+app.js+--->+index.html|

+-----------+ +------+ +----------+

Changing the code in this way would further hide the complexity that turns raw data into maps and markers. Adding new places by appending a few lines to a simple config file should be much less daunting than editing a file of JavaScript.

Next, let’s take this principle even further.

We can make E/P/D reusable in different cities

Eat/Play/Drink is a simple application that is deliberately and sensibly laser-focussed on things to do in San Francisco. But what if Sophia’s cousin, who lives in Austin (assume that Sophia has a cousin and that this cousin lives in Austin), wanted to make an Austin version of Eat/Play/Drink? He could copy and paste our source code, but in order to localize it for use in Austin he would need to edit a long list of specific files and lines. This would be fiddly and error-prone. On top of this, if we made improvements to the core Eat/Play/Drink codebase, he would have to manually copy these changes over and make sure that they didn’t accidentally overwrite his Austin-focussed updates to the code.

Sophia’s hypothetical cousin is probably very intelligent, and could probably figure out what to do given enough time. However, the more complex the app gets, the harder this migration will become. We should therefore go one step better. It would not take us much work to refactor the Eat/Play/Drink codebase into a generic, customizable framework that could trivially be reused by anyone to create an app to display their favorite places in their own city.

To do this, we would need to move all of the San-Francisco-specific pieces of the application into a config file (similar to places.json, described above), and have the rest of the application read all of its data from this file. Adapting the app for Austin should then require only replacing the San Francisco config file with one for Austin, with no changes to the core code required. This means that if Sophia were to make improvements to the core code, her cousin would be able to pull them in to his website without stomping over any of his Austin-based changes. Since all of his location-specific data is stored in the config file, updating the core code is entirely safe.

Which parts of the app are currently San-Francisco-specific? The places on the map (which we discussed above) are, of course. Add to this the co-ordinates where the map should be centred, the initial zoom-level of the map, the title of the home page, and the description text above the map. We also have to decide whether to stipulate that our app can only be used with the existing categories of eat, play, and drink, or whether to allow someone repurposing the app to choose their own categories, such as run, bike, and swim. If we made the latter choice, we would need to specify the categories in the config file too so that our app could generate the appropriate filter buttons.

The config file might look something like this:

{

"title": "EAT PLAY DRINK",

"description": "A list of the best places to eat, play, and drink in San Francisco, curated by a San Franciso native. Choose from the buttons below to filter your search.",

"categories": ["eat", "play", "drink"],

"map": {

"center": { "lat": 37.7749, "lng": -122.4194 },

"zoom": 12

},

"places": [

{

"coords": { "lat": 37.7638, "lng": -122.469 },

"content":

"<h3>San Tung</h3><p>Chinese restaurant with delicious dry fried chicken wings.</p><a href='https://goo.gl/maps/wiqva8qzW9bBoJRJ6' target='_blank'>Get directions</a>",

"category": "eat"

},

// ...etc...

]

}

After moving all the city-specific data into a config file, we would update app.js to read all of this extra data from it. We would also need to move responsibility for some pieces of data from index.html into app.js. For example, index.html currently has the description of the Eat/Play/Drink app hardcoded into it. We would instead need to make app.js responsible for dynamically inserting the description that it reads from the config file.

Now that we’ve seen how to extract more data into configuration files, let’s consider ways in we could enhance the markers data structure that we already have. I’m not actually certain that this next suggestion is a good idea, but it’s definitely educational so let’s discuss it anyway.

Extracting extra fields

You may notice that the content field of each element in the markers array always follows the same structure. For example:

<h3>Manna</h3><p>Hole-in-the-wall family-owned

Korean restaurant with the best tofu soup.</p>

<a href='https://goo.gl/maps/TkAFCrGrswH76hmT8'

target='_blank'>Get directions</a>

This and all other content values contain a heading, a description, and a link to directions. Can we exploit this consistency to improve our code? Maybe.

To answer this question, let’s start by making sure we understand the possible problems we are trying to solve. Suppose that we wanted to change the “Get directions” link to instead say simply “Directions”. At the moment we’d have to go through each place’s content field and manually update its value with the new link text. Or suppose that we wanted to allow someone not familiar with programming to add and update our data (as above). This person could probably copy-and-paste an example description and deduce that the words between <h3> and </h3> are probably a heading. However, this is a lot of unnecessary thinking to require of a person who only wants to make a note of a cool new coffee shop. There’s also a significant risk that they might accidentally delete a closing </p> tag or make some other typo. Come to think of it there’s a significant risk that I would accidentally delete a closing </p> tag too.

To solve these problems, we could extract each component of the content field into its own field, and write code to join these new fields together into a fully rendered block. So in our markers data structure, instead of this:

{

content: "<h3>Manna</h3><p>Hole-in-the-wall family-owned Korean restaurant with the best tofu soup.</p><a href='https://goo.gl/maps/TkAFCrGrswH76hmT8' target='_blank'>Get directions</a>",

// ...etc...

}

We would write this:

{

name: "Manna",

description: "Hole-in-the-wall family-owned Korean restaurant with the best tofu soup.",

directions_url: "https://goo.gl/maps/TkAFCrGrswH76hmT8",

// ...etc...

}

We would then write code to join the above parameters and turn them into the same fully-rendered output (<h3>Manna</h3><p>...etc...) that was previously stored wholesale in the content field.

This approach has several advantages. First, it further separates data from logic and presentation. Currently the markers array is responsible for raw information, but also some elements of presentation, such as whether the title should be displayed in <h3> or <h2> tags. However, markers should ideally contain only raw information, and the components of our program responsible for displaying this data (i.e. the rest of the app) should be responsible for making cosmetic choices.

Second, as discussed above, it makes adding and editing data simpler. It means that editors don’t have to know anything about HTML, and makes it harder for them to make silly typos.

However, the approach is not without its tradeoffs. By standardizing on a fixed structure made up of a set of fixed parameters, we make it easy to create info windows that follow this fixed structure. However, we also make it harder to create info windows that don’t. Currently the structure of an info window is to start with a title, then one paragraph of description, and finish with a link to directions. If you want two paragraphs of description, or an image, or you didn’t want a link to any directions, then you’re out of luck. You’ll have to update the code that turns our parameters into info window text so that it also accepts additional, optional parameters, such as description_2, image_url, hide_directions_link, and so on. If there aren’t many of these extra customizations then this might be a reasonable solution. But if there are a lot of them and you end up with twenty different configurable fields that sometimes interact with each other in surprising and complex ways (what should happen if hide_directions_link and directions_url are both set?) then you might find yourself wishing you had simply stuck with verbose, custom HTML instead of trying to make your life “easier”.

In situations like this I usually start off with whichever approach requires writing the least amount of code. Then I add specialized features only when I feel that I understand the problem that I’m trying to solve. One way to decide when to invest in writing more code is to wait until the problems that you think it will solve have really become problems. For example, I’ve claimed that splitting out the content field into multiple sub-fields will reduce the number of silly mistakes and bugs in the info window content. I’ve also claimed that it will make it easier to update the appearence of every info window at once. But how often have you actually introduced silly mistakes and bugs as a result of messing up HTML? And how often have you had to update the appearence of every info window at once? Was it really that annoying?

Don’t solve problems that you don’t have.

Trying to be too clever

Suppose that we did decide to refactor our data file in this way. We split out the content field into separate fields for name, description, and directions_url. At this point we notice that every directions_url is of the form https://goo.gl/maps/$UNIQUE_ID, and that we could potentially save a few characters by replacing the directions_url field with one called directions_google_id, which contains only the unique ID in the goo.gl/maps URL. For example:

{

name: "Manna",

description: "Hole-in-the-wall family-owned Korean restaurant with the best tofu soup.",

directions_google_id: "TkAFCrGrswH76hmT8",

// ...etc...

}

If we went down this path then our info-window-building code would be responsible for turning TkAFCrGrswH76hmT8 into https://goo.gl/maps/TkAFCrGrswH76hmT8 before inserting it into the directions link.

Making this change would certainly reduce the number of characters in our config file, and would indisputably reduce duplication of the string https://goo.gl/maps/. However, in my opinion these are very small benefits that don’t nearly outweigh the problems that it introduces.

For one thing, this change would make our config file less clear to read and update. “Create a goo.gl link but then chop off everything except the random characters at the end” is a more complicated instruction than “create a goo.gl link and copy it”. Worse, it would unnecessarily encode in our program the assumption that we always want to get our directions from Google Maps. Since we are still early in the lifecycle of the Eat/Play/Drink app, this could easily change, and we want to stay as flexible as possible. Suppose that we decided that for some places, Bing Maps gave better directions. We could add yet another field called directions_bing_id and write even more code to turn this into a Bing Maps URL, but now we’re starting to really add a lot more complexity for a nebulous gain. Wanting to save keystrokes is a good instinct, but isn’t always a good idea.

There are no hard rules about how data should be decomposed into parameters. It’s even easy to imagine further constraints that would make the above change a good idea. For example, maybe we’re being paid by Google to showcase Google Maps, and maybe it’s better for us to work with IDs instead of full URLs because this is the form in which Google sends us click statistics. You have to consider the tradeoffs for each individual case, and if in doubt err towards doing nothing.

Separating out your data and your logic can make your code cleaner and your life easier, and we haven’t even begun to fully exhaust the benefits. Suppose that the Eat/Play/Drink website keeps growing and adding more and more places. Eventually it will reach the point where storing all of our location data in JavaScript files, or even in separate config files, becomes unfeasible. Once this happens, we will want to switch to storing our data in a purpose-built database. This change will require a significant rearchitecting of our code, but having kept a clear separation between code and data will make the change substantially more straightforward. This is because we will only have to change the pieces of our code that deal with loading data from a data source. We can rip out the code that loads data from files and replace it with code that loads data from a database, and the code that is responsible for formatting and presenting the data won’t have to know or care what we have done. So long as this code gets passed data that describes places, it doesn’t much care where that data came from.

So next time you spot the opportunity to draw lines between your data and your logic, remember what Sophia did and give it a go.

Until next time:

- Subscribe to receive all future Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners in your inbox, once a fortnight, entirely free

- Subscribe to receive all my other blog posts in your inbox, once every now and then, also entirely free

- From the archives: A blogging style guide

- Follow me on Twitter

This post is part of my “Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners” series, which helps you make the leap from knowing how to cobble messy programs toether to writing clean, elegant code. Subscribe now to receive PFAB in your inbox, every fortnight, entirely free.

This week on Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners we’re going to start analyzing a brand new project. It’s an interactive website called Eat/Play/Drink, created by PFAB reader Sophia Li. Eat/Play/Drink presents the user with a curated map of places to eat, play, and drink, and allows the user to filter the map by category.

As with almost every program that we analyze in PFAB, Sophia’s program is already entirely functional and fit for purpose. You can even view it in action at https://sophiali.dev/eat-play-drink. The changes that we’re going to suggest would only start to become particularly important if the codebase grew larger or was being worked on by multiple programmers. For a small, personal side-project the changes should therefore be considered somewhat optional, but they’re still good opportunities for practice and learning.

Over the coming editions of PFAB we’re going to look at how Sophie could restructure her code so as to make it more “defensive”. This means anticipating the types of bugs that future programmers could accidentally introduce (Sophie-in-a-month counts as a future programmer!), and programming in a style that mitigates or prevents these bugs altogether.

But first I want to start our journey by discussing a design choice that Sophie made that I particularly like: enforcing the separation of logic and data.

Separating logic and data

Let’s start with a quick tour of the code (you can also read it in full on GitHub).

Eat/Play/Drink is built using HTML and JavaScript. If you aren’t familiar with these technologies then don’t worry - the concepts that we’re going to talk about are applicable to all other languages too. Roughly speaking, HTML is how you describe what a website looks like, and JavaScript is how you dynamically update it (for example, expanding a menu when a user clicks on a button).

HTML looks like this:

<!-- A simple website with an image and a button -->

<html>

<body>

<img id="main-pic" src="/images/photo-of-me.jpg" />

<button id="btn-change-pic" value="Change the pic!" />

</body>

</html>

JavaScript looks like this:

// When the user clicks on the button, change the image

$("#btn-change-pic").click(function() {

$("#main-pic").attr("src", "/images/photo-of-you.jpg");

});

The HTML for Eat/Play/Drink lives in a file called index.html ([view][index_html]). We’re not going to talk about this file much this week. The JavaScript lives in a file called app.js ([view][app_js]). It is responsible for creating Google Maps markers and “info boxes”, and for showing and hiding these components whenever a user clicks on a filter button.

At the top of app.js is an array called markers. This array contains details about each place on the Eat/Play/Drink map, including a place’s co-ordinates, category, and description:

const markers = [

{

coords: { lat: 37.7638, lng: -122.469 },

content:

"<h3>San Tung</h3><p>Chinese restaurant with delicious dry fried chicken wings.</p><a href='https://goo.gl/maps/wiqva8qzW9bBoJRJ6' target='_blank'>Get directions</a>",

category: "eat"

},

// ...etc...

}

I really like this array. It encapsulates all of the website’s data, keeping it completely isolated from the logic that is responsible for displaying it. This separation is valuable, for two reasons.

First, it’s almost always good to keep different components of your code separate from each other, regardless of what those components are. As we’ve talked about at length in previous PFABs, code that is well-separated into discrete components will, as a natural, inevitable consequence, tend to be easier to understand and work with.

Second, separating logic and data allows us to add new places to the Eat/Play/Drink app without needing to go anywhere near the code that is responsible for displaying those new places. Instead, we can add our new places to the markers array using a simple, well-defined format. We can hit save and refresh the page, and the new markers and info windows are immediately available to be clicked on.

As well as improving our lives in the short-term, separating logic and data opens up extra possibilities for the future too.

Future benefits of separating data and logic

We can make data updates even simpler

With only a little extra work, we could make it even easier for anyone to update our app’s code with new places, even if they aren’t a programmer. Non-programmers could probably already add a new element to the markers array in a pinch, but it might be intimidating to require them to edit a full JavaScript file that also contains functions, loops, if-statements, and so on. To alleviate this, we could move our places data to an entirely separate file (perhaps called places.json). This file would contain nothing but data, formatted as JSON. JSON stands for JavaScript Object Notation, and is a simple format for representing data. For example:

{

"places": [

{

"coords": { "lat": 37.7638, "lng": -122.469 },

"content":

"<h3>San Tung</h3><p>Chinese restaurant with delicious dry fried chicken wings.</p><a href='https://goo.gl/maps/wiqva8qzW9bBoJRJ6' target='_blank'>Get directions</a>",

"category": "eat"

}

// ...etc...

]

}

JSON files only represent data, and don’t contain any logic whatsoever. app.js would read and load the data from the JSON file, and then use it to perform all the presentation and other heavy lifting, just as it does today.

+-----------+ +------+ +----------+

|places.json+--->+app.js+--->+index.html|

+-----------+ +------+ +----------+

Changing the code in this way would further hide the complexity that turns raw data into maps and markers. Adding new places by appending a few lines to a simple config file should be much less daunting than editing a file of JavaScript.

Next, let’s take this principle even further.

We can make E/P/D reusable in different cities

Eat/Play/Drink is a simple application that is deliberately and sensibly laser-focussed on things to do in San Francisco. But what if Sophia’s cousin, who lives in Austin (assume that Sophia has a cousin and that this cousin lives in Austin), wanted to make an Austin version of Eat/Play/Drink? He could copy and paste our source code, but in order to localize it for use in Austin he would need to edit a long list of specific files and lines. This would be fiddly and error-prone. On top of this, if we made improvements to the core Eat/Play/Drink codebase, he would have to manually copy these changes over and make sure that they didn’t accidentally overwrite his Austin-focussed updates to the code.

Sophia’s hypothetical cousin is probably very intelligent, and could probably figure out what to do given enough time. However, the more complex the app gets, the harder this migration will become. We should therefore go one step better. It would not take us much work to refactor the Eat/Play/Drink codebase into a generic, customizable framework that could trivially be reused by anyone to create an app to display their favorite places in their own city.

To do this, we would need to move all of the San-Francisco-specific pieces of the application into a config file (similar to places.json, described above), and have the rest of the application read all of its data from this file. Adapting the app for Austin should then require only replacing the San Francisco config file with one for Austin, with no changes to the core code required. This means that if Sophia were to make improvements to the core code, her cousin would be able to pull them in to his website without stomping over any of his Austin-based changes. Since all of his location-specific data is stored in the config file, updating the core code is entirely safe.

Which parts of the app are currently San-Francisco-specific? The places on the map (which we discussed above) are, of course. Add to this the co-ordinates where the map should be centred, the initial zoom-level of the map, the title of the home page, and the description text above the map. We also have to decide whether to stipulate that our app can only be used with the existing categories of eat, play, and drink, or whether to allow someone repurposing the app to choose their own categories, such as run, bike, and swim. If we made the latter choice, we would need to specify the categories in the config file too so that our app could generate the appropriate filter buttons.

The config file might look something like this:

{

"title": "EAT PLAY DRINK",

"description": "A list of the best places to eat, play, and drink in San Francisco, curated by a San Franciso native. Choose from the buttons below to filter your search.",

"categories": ["eat", "play", "drink"],

"map": {

"center": { "lat": 37.7749, "lng": -122.4194 },

"zoom": 12

},

"places": [

{

"coords": { "lat": 37.7638, "lng": -122.469 },

"content":

"<h3>San Tung</h3><p>Chinese restaurant with delicious dry fried chicken wings.</p><a href='https://goo.gl/maps/wiqva8qzW9bBoJRJ6' target='_blank'>Get directions</a>",

"category": "eat"

},

// ...etc...

]

}

After moving all the city-specific data into a config file, we would update app.js to read all of this extra data from it. We would also need to move responsibility for some pieces of data from index.html into app.js. For example, index.html currently has the description of the Eat/Play/Drink app hardcoded into it. We would instead need to make app.js responsible for dynamically inserting the description that it reads from the config file.

Now that we’ve seen how to extract more data into configuration files, let’s consider ways in we could enhance the markers data structure that we already have. I’m not actually certain that this next suggestion is a good idea, but it’s definitely educational so let’s discuss it anyway.

Extracting extra fields

You may notice that the content field of each element in the markers array always follows the same structure. For example:

<h3>Manna</h3><p>Hole-in-the-wall family-owned

Korean restaurant with the best tofu soup.</p>

<a href='https://goo.gl/maps/TkAFCrGrswH76hmT8'

target='_blank'>Get directions</a>

This and all other content values contain a heading, a description, and a link to directions. Can we exploit this consistency to improve our code? Maybe.

To answer this question, let’s start by making sure we understand the possible problems we are trying to solve. Suppose that we wanted to change the “Get directions” link to instead say simply “Directions”. At the moment we’d have to go through each place’s content field and manually update its value with the new link text. Or suppose that we wanted to allow someone not familiar with programming to add and update our data (as above). This person could probably copy-and-paste an example description and deduce that the words between <h3> and </h3> are probably a heading. However, this is a lot of unnecessary thinking to require of a person who only wants to make a note of a cool new coffee shop. There’s also a significant risk that they might accidentally delete a closing </p> tag or make some other typo. Come to think of it there’s a significant risk that I would accidentally delete a closing </p> tag too.

To solve these problems, we could extract each component of the content field into its own field, and write code to join these new fields together into a fully rendered block. So in our markers data structure, instead of this:

{

content: "<h3>Manna</h3><p>Hole-in-the-wall family-owned Korean restaurant with the best tofu soup.</p><a href='https://goo.gl/maps/TkAFCrGrswH76hmT8' target='_blank'>Get directions</a>",

// ...etc...

}

We would write this:

{

name: "Manna",

description: "Hole-in-the-wall family-owned Korean restaurant with the best tofu soup.",

directions_url: "https://goo.gl/maps/TkAFCrGrswH76hmT8",

// ...etc...

}

We would then write code to join the above parameters and turn them into the same fully-rendered output (<h3>Manna</h3><p>...etc...) that was previously stored wholesale in the content field.

This approach has several advantages. First, it further separates data from logic and presentation. Currently the markers array is responsible for raw information, but also some elements of presentation, such as whether the title should be displayed in <h3> or <h2> tags. However, markers should ideally contain only raw information, and the components of our program responsible for displaying this data (i.e. the rest of the app) should be responsible for making cosmetic choices.

Second, as discussed above, it makes adding and editing data simpler. It means that editors don’t have to know anything about HTML, and makes it harder for them to make silly typos.

However, the approach is not without its tradeoffs. By standardizing on a fixed structure made up of a set of fixed parameters, we make it easy to create info windows that follow this fixed structure. However, we also make it harder to create info windows that don’t. Currently the structure of an info window is to start with a title, then one paragraph of description, and finish with a link to directions. If you want two paragraphs of description, or an image, or you didn’t want a link to any directions, then you’re out of luck. You’ll have to update the code that turns our parameters into info window text so that it also accepts additional, optional parameters, such as description_2, image_url, hide_directions_link, and so on. If there aren’t many of these extra customizations then this might be a reasonable solution. But if there are a lot of them and you end up with twenty different configurable fields that sometimes interact with each other in surprising and complex ways (what should happen if hide_directions_link and directions_url are both set?) then you might find yourself wishing you had simply stuck with verbose, custom HTML instead of trying to make your life “easier”.

In situations like this I usually start off with whichever approach requires writing the least amount of code. Then I add specialized features only when I feel that I understand the problem that I’m trying to solve. One way to decide when to invest in writing more code is to wait until the problems that you think it will solve have really become problems. For example, I’ve claimed that splitting out the content field into multiple sub-fields will reduce the number of silly mistakes and bugs in the info window content. I’ve also claimed that it will make it easier to update the appearence of every info window at once. But how often have you actually introduced silly mistakes and bugs as a result of messing up HTML? And how often have you had to update the appearence of every info window at once? Was it really that annoying?

Don’t solve problems that you don’t have.

Trying to be too clever

Suppose that we did decide to refactor our data file in this way. We split out the content field into separate fields for name, description, and directions_url. At this point we notice that every directions_url is of the form https://goo.gl/maps/$UNIQUE_ID, and that we could potentially save a few characters by replacing the directions_url field with one called directions_google_id, which contains only the unique ID in the goo.gl/maps URL. For example:

{

name: "Manna",

description: "Hole-in-the-wall family-owned Korean restaurant with the best tofu soup.",

directions_google_id: "TkAFCrGrswH76hmT8",

// ...etc...

}

If we went down this path then our info-window-building code would be responsible for turning TkAFCrGrswH76hmT8 into https://goo.gl/maps/TkAFCrGrswH76hmT8 before inserting it into the directions link.

Making this change would certainly reduce the number of characters in our config file, and would indisputably reduce duplication of the string https://goo.gl/maps/. However, in my opinion these are very small benefits that don’t nearly outweigh the problems that it introduces.

For one thing, this change would make our config file less clear to read and update. “Create a goo.gl link but then chop off everything except the random characters at the end” is a more complicated instruction than “create a goo.gl link and copy it”. Worse, it would unnecessarily encode in our program the assumption that we always want to get our directions from Google Maps. Since we are still early in the lifecycle of the Eat/Play/Drink app, this could easily change, and we want to stay as flexible as possible. Suppose that we decided that for some places, Bing Maps gave better directions. We could add yet another field called directions_bing_id and write even more code to turn this into a Bing Maps URL, but now we’re starting to really add a lot more complexity for a nebulous gain. Wanting to save keystrokes is a good instinct, but isn’t always a good idea.

There are no hard rules about how data should be decomposed into parameters. It’s even easy to imagine further constraints that would make the above change a good idea. For example, maybe we’re being paid by Google to showcase Google Maps, and maybe it’s better for us to work with IDs instead of full URLs because this is the form in which Google sends us click statistics. You have to consider the tradeoffs for each individual case, and if in doubt err towards doing nothing.

Separating out your data and your logic can make your code cleaner and your life easier, and we haven’t even begun to fully exhaust the benefits. Suppose that the Eat/Play/Drink website keeps growing and adding more and more places. Eventually it will reach the point where storing all of our location data in JavaScript files, or even in separate config files, becomes unfeasible. Once this happens, we will want to switch to storing our data in a purpose-built database. This change will require a significant rearchitecting of our code, but having kept a clear separation between code and data will make the change substantially more straightforward. This is because we will only have to change the pieces of our code that deal with loading data from a data source. We can rip out the code that loads data from files and replace it with code that loads data from a database, and the code that is responsible for formatting and presenting the data won’t have to know or care what we have done. So long as this code gets passed data that describes places, it doesn’t much care where that data came from.

So next time you spot the opportunity to draw lines between your data and your logic, remember what Sophia did and give it a go.

Until next time:

- Subscribe to receive all future Programming Feedback for Advanced Beginners in your inbox, once a fortnight, entirely free

- Subscribe to receive all my other blog posts in your inbox, once every now and then, also entirely free

- From the archives: A blogging style guide

- Follow me on Twitter