How does a TCP Reset Attack work?

27 Apr 2020

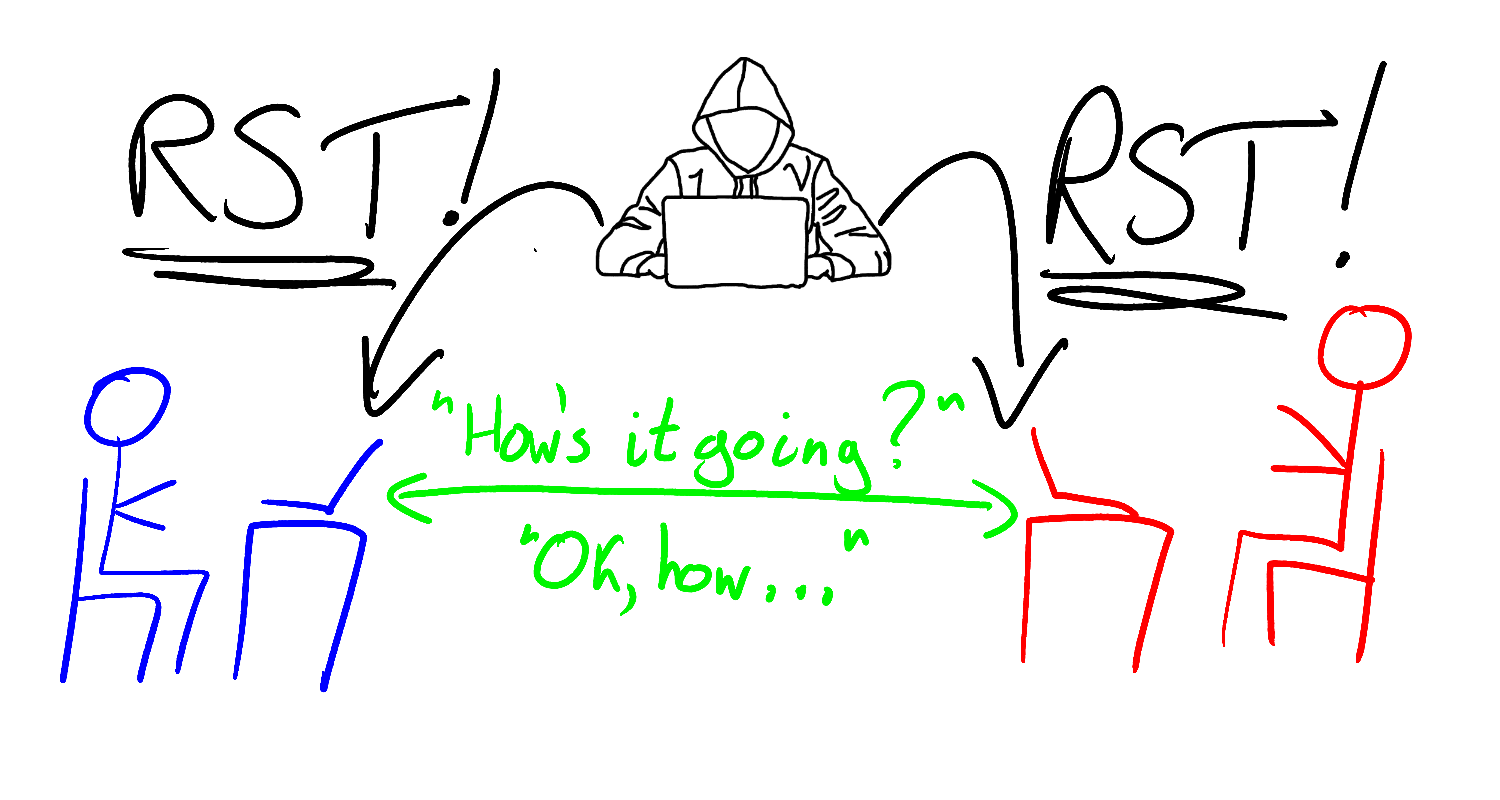

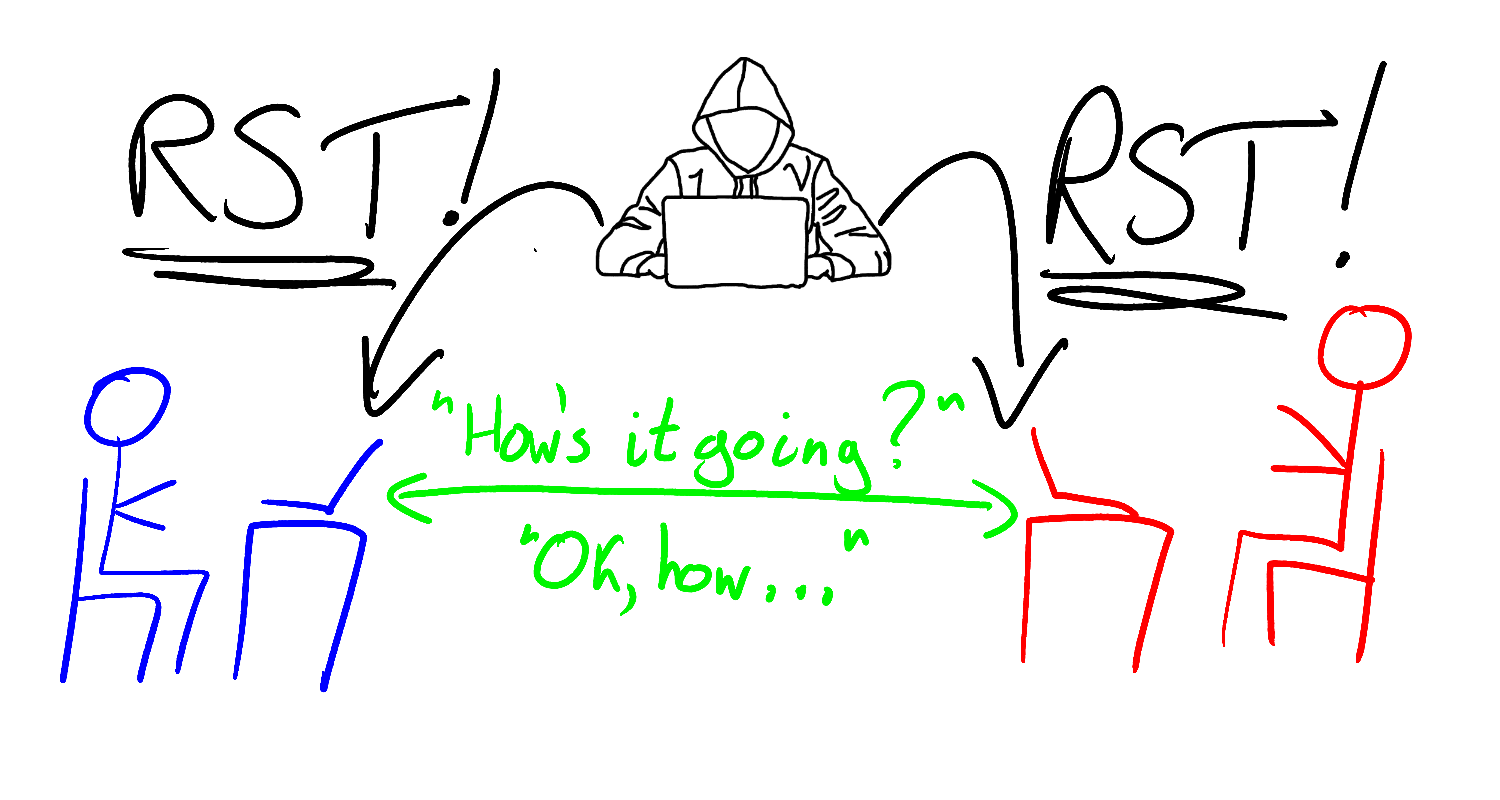

A TCP reset attack is executed using a single packet of data, no more than a few bytes in size. A spoofed TCP segment, crafted and sent by an attacker, tricks two victims into abandoning a TCP connection, interrupting possibly vital communications between them.

The attack has had real-world consequences. Fear of it has caused mitigating changes to be made to the TCP protocol itself. The attack is believed to be a key component of China’s Great Firewall, used by the Chinese government to censor the internet inside China. Despite this weighty biography, understanding the attack doesn’t require deep prior knowledge of networking or TCP. Indeed, understanding the attack’s intricacies will teach you a great deal about the particulars of the TCP protocol, and, as we will soon see, you can even execute the attack against yourself using only a single laptop.

In this post we’re going to:

- Learn the basics of the TCP protocol

- Learn how the attack works

- Execute the attack against ourselves using a simple Python script

Before we analyze the mechanics of the attack, let’s begin by seeing how it is used in the real world.

How is the TCP reset attack used in the Great Firewall?

The Great Firewall (GFW) is a collection of systems and techniques used by the Chinese government to censor the internet for users inside China. The GFW actively blocks and kills connections to servers inside and outside of the country, as well as passively monitoring internet traffic for proscribed content.

To prevent users from even connecting to forbidden servers, the GFW uses techniques like DNS pollution and IP blocking (both stories for another time). However, the GFW may sometimes also want to allow a connection to be made, but to then kill it halfway through. This could be because they want to perform slow, out-of-band analysis on the connection, such as correlating it with other activity. Or it could be because they want to analyze the data exchanged over a connection and use this information to decide whether to allow or block it. For example, they may want to generally allow traffic to a news website, but to censor specific videos containing banned keywords.

To do this, the GFW needs tools that are capable of killing already-established connections. One such tool that they use is the TCP reset attack.

How does a TCP reset attack work?

In a TCP reset attack, an attacker kills a connection between two victims by sending one or both of them fake messages telling them to stop using the connection immediately. These messages are called TCP reset segments. In normal, non-nefarious operations, computers send TCP reset segments whenever they receive unexpected TCP traffic and they want its sender to stop sending it.

A TCP reset attack exploits this mechanism to trick victims into prematurely closing TCP connections by sending them fake reset segments. If a fake reset segment is crafted correctly, the receiver will accept it as valid and close their side of the connection, preventing the connection from being used to exchange further information. The victims can create a new TCP connection in an attempt to resume their communications, but the attacker may be able to reset this new connection too. Fortunately, because it takes the attacker time to assemble and send their spoofed packet, reset attacks are only really effective against long-lived connections. Short-lived connections, for example those used to transmit small webpages, will typically have already fulfilled their purpose by the time an attacker is able to attempt to reset them.

Sending spoofed TCP segments is in one sense easy, since neither TCP nor IP comes with any built-in way to verify a sender’s identity. There is an extension to IP which does provide authentication, called IPSec. However, it is not widely used. Internet service providers are supposed to refuse to transit IP packets that claim to have come from a clearly-spoofed IP address, but such verification is anecdotally said to be patchy. All a receiver can do is to take the source IP address and port inside a packet or segment at face value, and where possible use higher-level protocols, such as TLS, to verify the sender’s identity. However, since TCP reset packets are part of the TCP protocol itself, they cannot be validated using these higher-level protocols.

Despite the ease with which spoofed segments can be sent, crafting the right spoofed segment and executing a successful TCP reset attack can still be challenging. In order to see why, we’ll need to understand how the TCP protocol works.

How the TCP protocol works

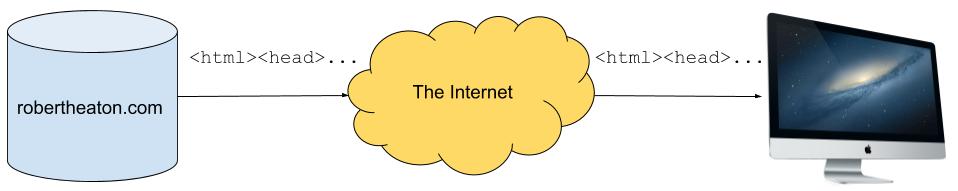

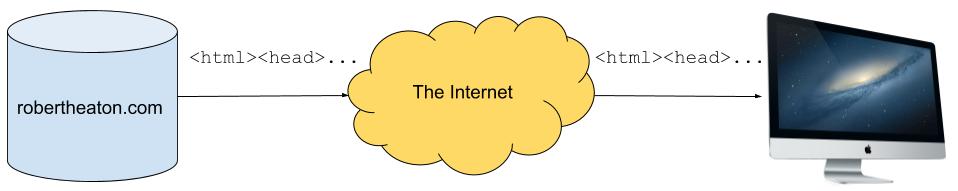

The goal of the TCP protocol is to send a recipient a perfect copy of a piece of data. For example, if my server sends your computer the HTML for my website over a TCP connection, your computer’s TCP stack (the part of its operating system that handles TCP) should be able to output my HTML in the exact form and order that my server sent it.

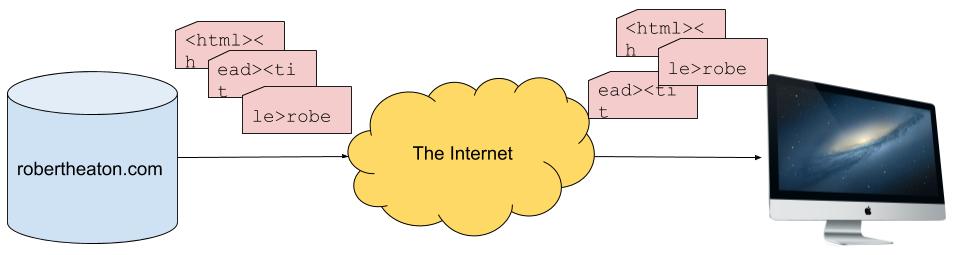

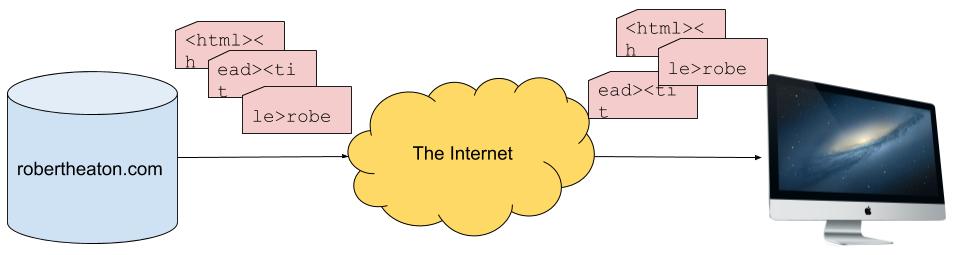

However, my HTML is not sent over the internet in such a perfect, ordered form. Instead, it is broken up into many small chunks (known as TCP segments), which are each sent separately over the internet and reconstituted back into the order in which they were sent by your computer’s TCP stack. This reconsituted output is known as a TCP stream. Each TCP segment is sent in its own IP packet, although we don’t need to understand any of the details of IP for this attack.

Reconstructing segments into a stream requires care, because the internet is not reliable. TCP segments may get dropped. They may arrive out of order; be sent twice; get corrupted; or have any number of other mishaps befall them. The job of the TCP protocol is therefore to provide reliable communication over an unreliable network. TCP achieves this goal by requiring the two sides of a connection to keep in close contact with each other, constantly reporting which pieces of data they have received. This allows senders to infer which data a receiver has not yet received, and to re-send any data that may have been lost.

In order to understand how this process works, we need to understand how senders and receivers use TCP sequence numbers to label and keep track of data sent over TCP.

TCP sequence numbers

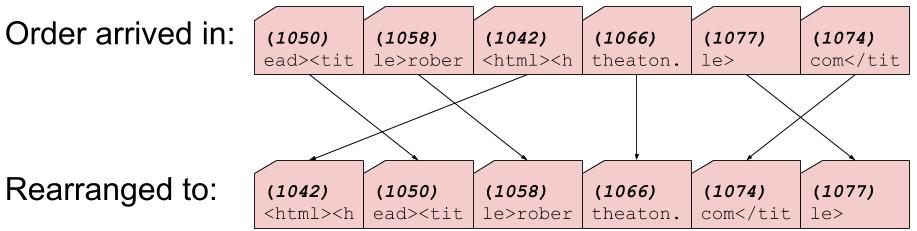

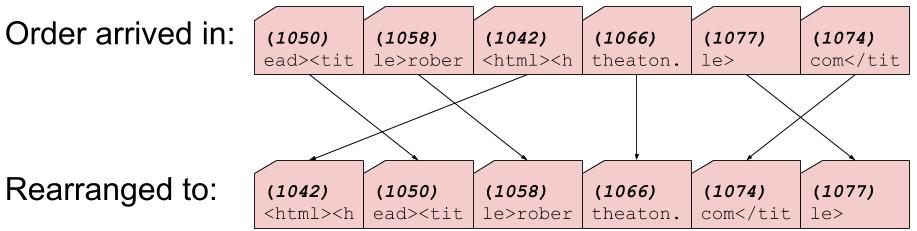

Every byte sent over a TCP connection has an ordered sequence number, assigned to it by its sender. Receiving machines use sequence numbers to shift the data that they receive back into its original order.

When two machines negotiate a TCP connection, each machine sends the other a random initial sequence number. This is the sequence number that the machine will assign to the first byte of data that it sends. Every subsequent byte is assigned the sequence number of the previous byte, plus 1. TCP segments contain TCP headers, which are metadata attached to the start of a segment. The sequence number of the first byte in a segment’s body is included in that segment’s TCP header.

Note that TCP connections are bi-directional, which means that data can be sent in both directions and that each machine in a TCP connection acts as both a sender and a receiver. Because of this, each machine must assign and manage its own, independent set of sequence numbers.

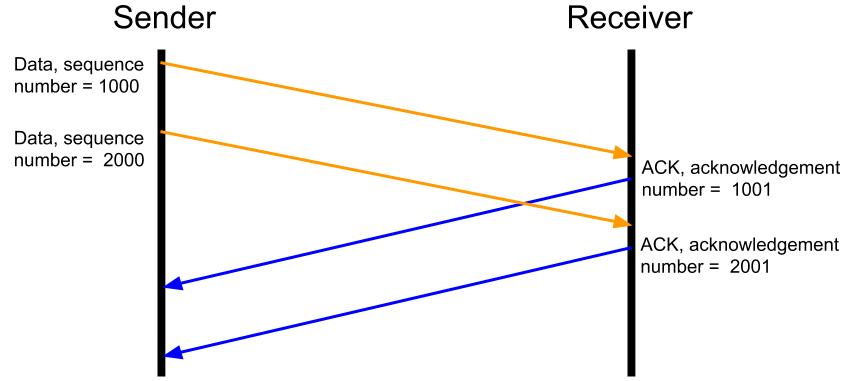

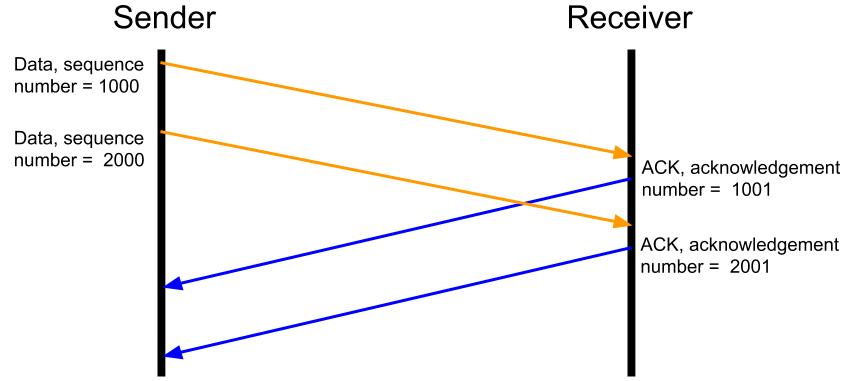

Acknowledging receipt of data

When a machine receives a TCP segment, it notifies the segment’s sender that it has been received. The receiver does this by sending an ACK (short for “acknowledge”) segment, containing the sequence number of the next byte that it expects to receive from the sender. The sender uses this information to infer that the receiver has successfully received all other bytes up to this number.

An ACK segment is denoted by the presence of the ACK flag and a corresponding acknowledgement number in the segment’s TCP headers. TCP has a total of 6 flags, including - as we will soon see - the RST (short for “reset”) flag that denotes a reset segment.

Sidenote - the TCP protocol also allows for selective ACKs, which are sent when a receiver has received some, but not all, segments in a range. For example “I’ve received bytes 1000-3000 and 4000-5000, but not 3001-3999”. For simplicity, we will ignore selective ACKs in our discussion of TCP reset attacks.

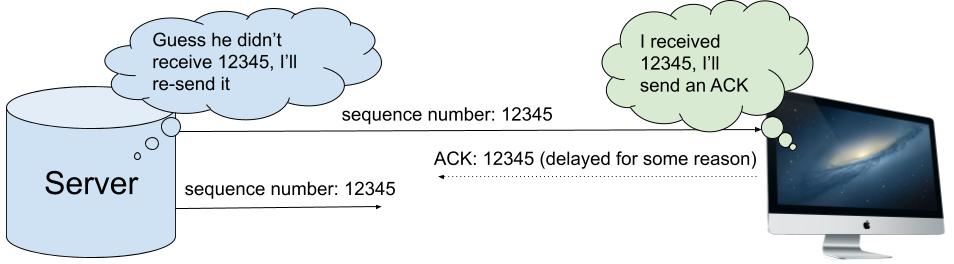

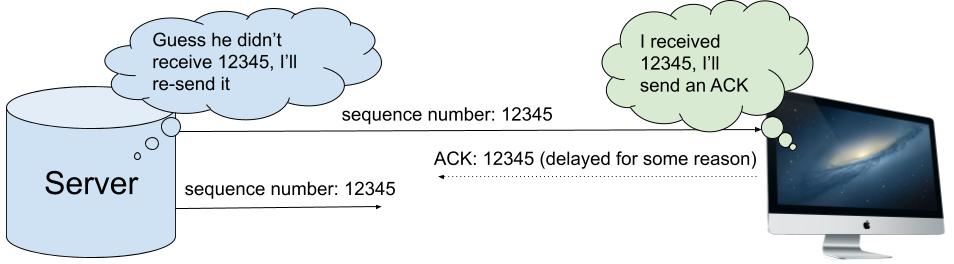

If a sender sends data but does not receive an ACK for it within a certain time interval, then the sender assumes that the data was lost and re-sends it, tagged with the same sequence numbers. This means that if the receiver receives the same bytes twice, it can trivially use sequence numbers to de-duplicate them without corrupting the stream. A receiver might receive duplicate data because an original segment arrived late, after it had been re-sent; or because an original segment arrived successfully but the corresponding ACK was lost on its way back to the sender.

So long as such duplicate data is relatively infrequent, the overhead that it causes is unproblematic. If all data eventually reaches its receiver, and the corresponding ACKs eventually reach their sender, the TCP connection is doing its job.

Choosing a sequence number for spoofed segment

As part of constructing a spoofed RST segment, an attacker needs to give their segment a sequence number. Receivers are happy to accept segments with non-sequential sequence numbers, and to take responsibility for stitching them back into the correct order. However, this tolerance is limited. If a receiver receives a segment with a sequence number that is “too” out of order then the receiver will discard the segment.

A successful TCP reset attack therefore requires a believable sequence number. But what counts as a believable sequence number? For most segments (although, as we will see, not RSTs), the answer is determined by the receiver’s TCP window size.

TCP window size

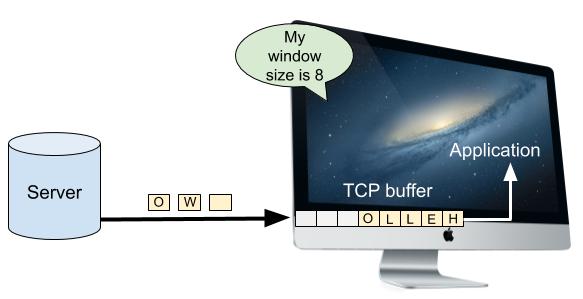

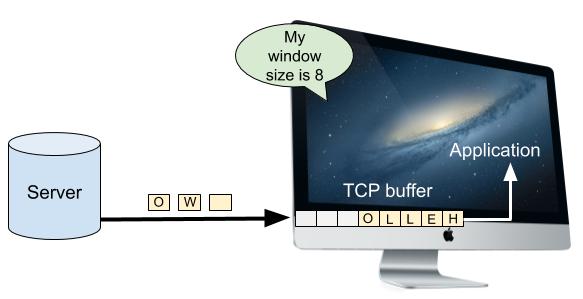

Imagine an ancient, early-1990s computer, connected to a modern gigabit fibre network. The lightning-quick network can feed data to the venerable computer at neckbreaking speed, much faster than the computer can handle it. This would not be helpful, because a TCP segment can’t be considered to have been received until the receiver has been able to process it.

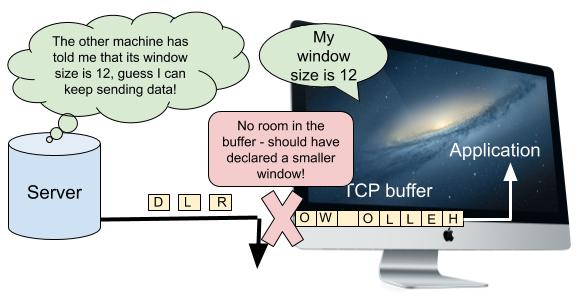

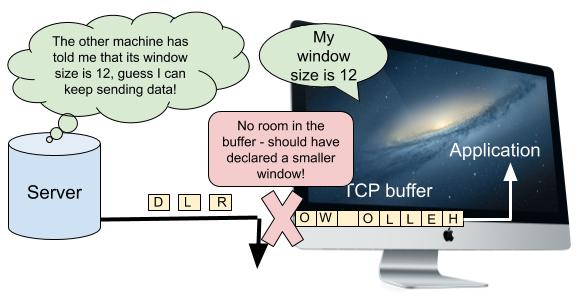

Computers have a TCP buffer where newly-arrived data waits to be processed while the computer works through any data that arrived ahead of it. However, this buffer has a finite size. If the receiver is unable to keep up with the volume of data that the network is feeding it, the buffer will fill up. Once the buffer is completely full, the receiver will have no choice but to drop excess data on the floor. The receiver won’t send an ACK for the dropped data, and so the sender will have to re-send it once space opens up in the receiver’s buffer. It doesn’t matter how fast a network can send data if the receiver can’t keep up.

Imagine also an over-zealous friend who mails you a torrent of letters faster than you can read them. You have some amount of buffer space inside your mailbox, but once your mailbox fills up any overflow letters will spill out onto the floor and be eaten by foxes and other critters. Your friend will have to re-send the now-digested letters once you’ve had time to retrieve their earlier missives. Sending too many letters or too much data when the recipient is unable to process it is a pure waste of energy and bandwidth.

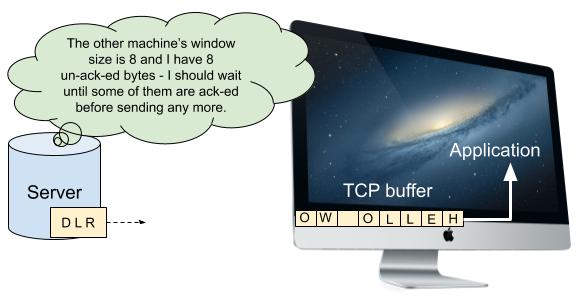

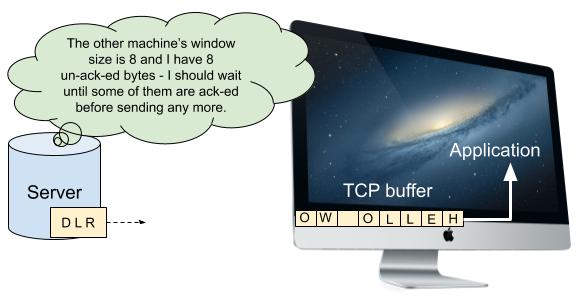

How much data is too much? How does a sender know when to send more data and when to hold back? This is where the TCP window size comes in. A receiver’s window size is the maximum number of unacknowledged bytes that a sender may have in flight to it at any one time. Suppose that a receiver advertises a window size of 100,000 (we’ll see how it broadcasts this value shortly), and so a sender fires off 100,000 bytes. Let’s say that by the time the sender has sent the 100,000th byte, the receiver has sent ACKs for the first 10,000 of those bytes. This means that there are 90,000 bytes still un-acked. Since the window size is 100,000, this leaves 10,000 more bytes that the sender can send before it has to wait for more ACKs. After sending 10,000 extra bytes, if there have been no further ACKs then the sender will have hit the limit of 100,000 un-acknowledged bytes. The sender will therefore have to wait and stop sending data (apart from re-sending data that it believes may be lost) until it receives some ACKs.

Each side of a TCP connection informs the other of its window size during the initial handshake that is performed when the connection is opened. Window sizes may also be adjusted dynamically during a connection. A computer with a large TCP buffer might declare a large window size in order to maximize throughput. This allows a machine communicating with it to continuously shovel data into the TCP connection, without having to pause and wait for any of it to be acknowledged. By contrast, a computer with a small TCP buffer might be forced to declare a small window size. Senders may sometimes fill up the window and be forced to wait until some of their segments have been acknowledged before continuing. This sacrifices some amount of throughput, but is necessary in order to prevent the receiver’s TCP buffer from overflowing.

The TCP window size is a hard limit on the amount of unacknowledged data that may be in-flight. We can use it to calculate the maximum possible sequence number (which I’m calling max_seq_no in the below equation) that a sender could have sent at a given time:

max_seq_no = max_acked_seq_no + window_size

max_acked_seq_no is the maximum sequence number that the receiver has sent an ACK for. It is the maximum sequence number that the sender knows that the receiver has received successfully. Since the sender is only allowed to have window_size unacknowledged bytes in-flight, the maximum sequence number that it can send is max_acked_seq_no + window_size.

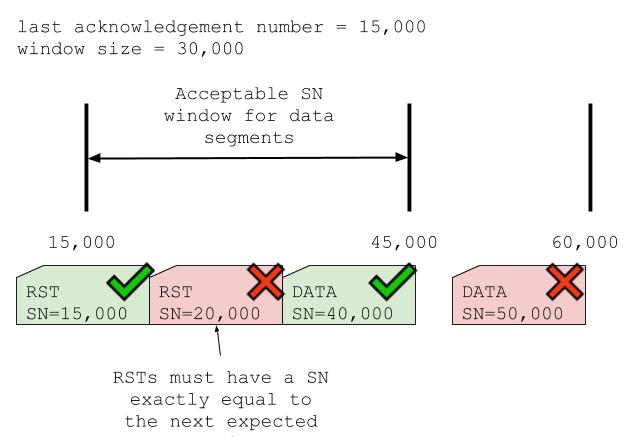

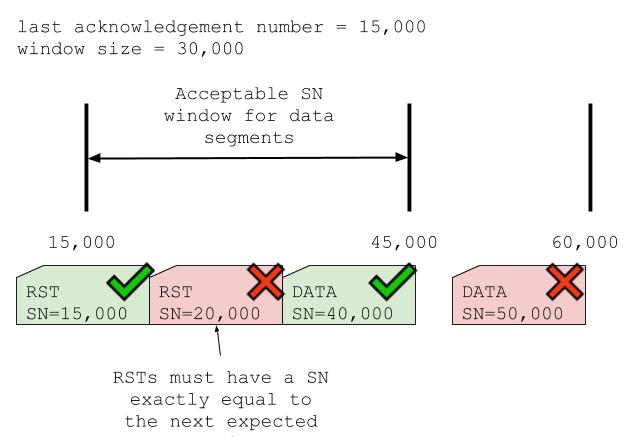

Because of this, the TCP specification decrees that the receiver should ignore any data that it receives with sequence numbers outside its acceptable window. For example, if a receiver has acknowledged all bytes up to 15,000, and its window size is 30,000, then the receiver will accept any data with a sequence number between 15,000 and (15,000 + 30,000 = 45,000). By contrast, the receiver will completely ignore data with a sequence number outside this range. If a segment contains some data that is within its window, and some that is outside, then the data inside the window will be accepted and acknowledged, but the data outside it will be dropped. Note that we are still ignoring the possibility of selective ACKs, which we touched on briefly at the start of this post.

For most TCP segments, this rule gives the range of acceptable sequence numbers. However, as previously noted, the restrictions on RST segments are even stricter than those for normal, data-transmission, segments. As we will soon see, this is in order to make a type of TCP reset attack called a blind TCP reset attack more difficult.

Acceptable sequence numbers for RST segments

Normal segments are accepted if they have a sequence number anywhere between the next expected sequence number and that number plus the window size. However, RST packets are only accepted if they have a sequence number exactly equal to the next expected sequence number. Consider once again our previous example, in which the receiver has sent an acknowledgement number of 15,000. In order to be accepted, a RST packet must have a sequence number of exactly 15,000. If the receiver receives a RST segment with a sequence number that is not exactly 15,000, it will not accept it.

If the sequence number is completely out of range then the receiver ignores the segment entirely. If, however, it is within the window of expected sequence numbers, then the receiver sends back a “challenge ACK”. This is a segment which tells the sender that the RST segment had the wrong sequence number. It also tells the sender actual sequence number that the receiver was expecting. The sender can use the information in the challenge ACK to re-construct and re-send its RST.

Before 2010, the TCP protocol did not impose these additional restrictions on RST segments. RST segments were accepted or rejected according to the same rules as any other segment. However, this made blind TCP reset attacks too easy.

Blind TCP reset attacks

If an attacker is able to intercept the traffic being exchanged by their victims, the attacker can read the sequence and acknowledgment numbers on their victims’ TCP packets. They can use this information to decide what sequence numbers they should give their spoofed RST segments. By contrast, if the attacker cannot intercept their victims’ traffic then they will not know what sequence numbers they should insert. However, they can still blast out as many RST segments with as many different sequence numbers as possible and hope that one of them turns out to be correct. This is known as a blind TCP reset attack.

As we have already noted, in the original version of the TCP protocol an attacker only had to guess a RST sequence number somewhere within the receiver’s TCP window. A paper called “Slipping in the Window” showed that this made a successful blind attack too easy, since the attacker only needed to send a few tens of thousands of segments in order to be almost assured of success. To counter this, the rules for when a receiver should accept a RST segment were changed to the more restrictive criterion described above. With the new rules in force, blind TCP reset attacks require sending out millions of segments, making them all-but intractable. See RFC-5963 for more details.

Executing a TCP reset attack against ourselves

NOTE: I’ve tested this process on OSX, but have received several reports of it not working as intended on Linux.

We now know everything about executing a TCP reset attack. An attacker has to:

- Watch (or sniff) the network traffic being exchanged between our two victims

- Sniff a TCP segment with the

ACK flag enabled and read its acknowledgement number

- Craft a spoofed TCP segment with the

RST flag enabled, and a sequence number equal to the acknowledgement number of the intercepted segment (note that this assumes that data is exchanged over the connection slowly, and so our choice of sequence number does not quickly go out of date. We can fire off multiple RST segments with a range of sequence numbers if we want to increase our chance of success)

- Send the spoofed segments to one or both of our victims, hopefully causing them to terminate their TCP connection

To practice, let’s execute a TCP attack against ourselves using a single computer talking to itself through localhost. To do this we need to:

- Set up a TCP connection between two terminal windows

- Write an attack program that sniffs the traffic

- Modify the attack program to craft and send spoofed

RST segments

Let’s begin.

1. Set up a TCP connection between two terminal windows

We set up our TCP connection using a tool called netcat, which comes pre-installed on many operating systems. Any other TCP client would do the job too. In our first terminal window we run:

nc -nvl 8000

This command starts a TCP server on your local machine, listening on port 8000. In our second terminal window we run:

nc 127.0.0.1 8000

This command attempts to make a TCP connection with the machine at IP address 127.0.0.1 on port 8000. These two terminal windows should now have a TCP connection established between them. Try typing some words into one window - the data should be sent over the TCP connection and appear in the other window.

2. Sniff the traffic

We write an attack program to sniff our connection’s traffic using scapy, a popular Python networking library. This program uses scapy read the data exchanged between our two terminal windows, despite not being part of the connection.

The code is in my GitHub repo. It sniffs traffic on our connection and prints it to the terminal. The core of the code is the call to scapy’s sniff method at the bottom of the file:

t = sniff(

iface='lo0',

lfilter=is_packet_tcp_client_to_server(localhost_ip, localhost_server_port, localhost_ip),

prn=log_packet,

count=50)

This snippet tells scapy to sniff packets on the lo0 interface, and to log details about all packets that are part of our TCP connection. The parameters are:

iface - tells scapy to listen on the lo0, or localhost, network interfacelfilter - a filter function that tells scapy to ignore all packets that aren’t part of a connection that is between two localhost IPs and is on our server’s port. This filtering is necessary because there are many other programs running on our machine that use the lo0 interface. We want to ignore any packets that aren’t part of our experiment.prn - a function through which scapy should run each packet that matches the lfilter function. The function in the example above simply logs the packet to the terminal. In the next step we will modify this function to also send our RST segments.count - the number of packets we want scapy to sniff before returning.

To test out this program, set up the TCP connection as in step 1. Clone my GitHub repo, follow the setup instructions, and run the program in a third terminal window. Type some text into one of the terminals in the TCP connection. You should see the program start to log information about the connection’s segments.

3. Send spoofed RST packets

With a connection established and a program able to sniff the TCP segments passing through it, all that remains is for us to modify our program to execute a TCP reset attack by sending spoofed RST segments. To do this, we modify the prn function (see parameter list above) that scapy calls on packets that match our lfilter function. In the modified version of this function, instead of simply logging a matching packet, we inspect the packet, pull off the necessary parameters, and use those parameters to construct and send a RST segment.

For example, suppose we intercept a segment going from (src_ip, src_port) to (dst_ip, dst_port). It has the ACK flag set, and an acknowledgement number of 100,000. In order to craft and send our segment we:

- Switch the destination and source IPs, as well as the destination and source ports. This is because our packet is a response to the intercepted packet. Our packet’s source should be the original packet’s destination, and vice-versa.

- Turn on the segment’s

RST flag, since this is what indicates the the segment is a RST

- Set the sequence number to be the exact acknowledgement number from the packet that we intercepted, since this is the next sequence number that the sender expects to receive

- Call

scapy’s send method to send the segment to our victim, the source of our intercepted packet

To modify our previous program to do this, uncomment this line and comment out the line above it.

We are now ready to execute the attack in full. Set up the TCP connection as in step 1. Run the attack program from step 2 in a third terminal window. Then type some text into one of the terminals in the TCP connection. The terminal that you typed into should have its TCP connection abruptly and mystifyingly killed. The attack is complete!

Further work

- Continue to experiment with the attack apparatus. See what happens if you add or subtract 1 from the sequence number of the

RST packet. Convince yourself that it does indeed need to be exactly equal to the ack value of the intercepted packet.

- Download Wireshark and use it to listen on the

lo0 interface while you execute the attack. This will allow you to see all the details of every TCP segment exchanged over the connection, including the spoofed RST. Use the filter ip.src == 127.0.0.1 && ip.dst == 127.0.0.1 && tcp.port == 8000 to filter out extraneous traffic from other programs.

- Make the attack harder to execute by sending a continuous stream of data over the connection. This will make it harder for our script to choose the correct sequence number for its

RST segments, because by the time the RST segment arrives at our victim the victim may have received further legitimate data, increasing its expected next sequence number. To counter this effect we can fire off multiple RST packets, each with different sequence numbers.

In conclusion

The TCP reset attack is both deep and simple. Good luck with your experimentation, and please do let me know if you have any questions or comments.

A TCP reset attack is executed using a single packet of data, no more than a few bytes in size. A spoofed TCP segment, crafted and sent by an attacker, tricks two victims into abandoning a TCP connection, interrupting possibly vital communications between them.

The attack has had real-world consequences. Fear of it has caused mitigating changes to be made to the TCP protocol itself. The attack is believed to be a key component of China’s Great Firewall, used by the Chinese government to censor the internet inside China. Despite this weighty biography, understanding the attack doesn’t require deep prior knowledge of networking or TCP. Indeed, understanding the attack’s intricacies will teach you a great deal about the particulars of the TCP protocol, and, as we will soon see, you can even execute the attack against yourself using only a single laptop.

In this post we’re going to:

- Learn the basics of the TCP protocol

- Learn how the attack works

- Execute the attack against ourselves using a simple Python script

Before we analyze the mechanics of the attack, let’s begin by seeing how it is used in the real world.

How is the TCP reset attack used in the Great Firewall?

The Great Firewall (GFW) is a collection of systems and techniques used by the Chinese government to censor the internet for users inside China. The GFW actively blocks and kills connections to servers inside and outside of the country, as well as passively monitoring internet traffic for proscribed content.

To prevent users from even connecting to forbidden servers, the GFW uses techniques like DNS pollution and IP blocking (both stories for another time). However, the GFW may sometimes also want to allow a connection to be made, but to then kill it halfway through. This could be because they want to perform slow, out-of-band analysis on the connection, such as correlating it with other activity. Or it could be because they want to analyze the data exchanged over a connection and use this information to decide whether to allow or block it. For example, they may want to generally allow traffic to a news website, but to censor specific videos containing banned keywords.

To do this, the GFW needs tools that are capable of killing already-established connections. One such tool that they use is the TCP reset attack.

How does a TCP reset attack work?

In a TCP reset attack, an attacker kills a connection between two victims by sending one or both of them fake messages telling them to stop using the connection immediately. These messages are called TCP reset segments. In normal, non-nefarious operations, computers send TCP reset segments whenever they receive unexpected TCP traffic and they want its sender to stop sending it.

A TCP reset attack exploits this mechanism to trick victims into prematurely closing TCP connections by sending them fake reset segments. If a fake reset segment is crafted correctly, the receiver will accept it as valid and close their side of the connection, preventing the connection from being used to exchange further information. The victims can create a new TCP connection in an attempt to resume their communications, but the attacker may be able to reset this new connection too. Fortunately, because it takes the attacker time to assemble and send their spoofed packet, reset attacks are only really effective against long-lived connections. Short-lived connections, for example those used to transmit small webpages, will typically have already fulfilled their purpose by the time an attacker is able to attempt to reset them.

Sending spoofed TCP segments is in one sense easy, since neither TCP nor IP comes with any built-in way to verify a sender’s identity. There is an extension to IP which does provide authentication, called IPSec. However, it is not widely used. Internet service providers are supposed to refuse to transit IP packets that claim to have come from a clearly-spoofed IP address, but such verification is anecdotally said to be patchy. All a receiver can do is to take the source IP address and port inside a packet or segment at face value, and where possible use higher-level protocols, such as TLS, to verify the sender’s identity. However, since TCP reset packets are part of the TCP protocol itself, they cannot be validated using these higher-level protocols.

Despite the ease with which spoofed segments can be sent, crafting the right spoofed segment and executing a successful TCP reset attack can still be challenging. In order to see why, we’ll need to understand how the TCP protocol works.

How the TCP protocol works

The goal of the TCP protocol is to send a recipient a perfect copy of a piece of data. For example, if my server sends your computer the HTML for my website over a TCP connection, your computer’s TCP stack (the part of its operating system that handles TCP) should be able to output my HTML in the exact form and order that my server sent it.

However, my HTML is not sent over the internet in such a perfect, ordered form. Instead, it is broken up into many small chunks (known as TCP segments), which are each sent separately over the internet and reconstituted back into the order in which they were sent by your computer’s TCP stack. This reconsituted output is known as a TCP stream. Each TCP segment is sent in its own IP packet, although we don’t need to understand any of the details of IP for this attack.

Reconstructing segments into a stream requires care, because the internet is not reliable. TCP segments may get dropped. They may arrive out of order; be sent twice; get corrupted; or have any number of other mishaps befall them. The job of the TCP protocol is therefore to provide reliable communication over an unreliable network. TCP achieves this goal by requiring the two sides of a connection to keep in close contact with each other, constantly reporting which pieces of data they have received. This allows senders to infer which data a receiver has not yet received, and to re-send any data that may have been lost.

In order to understand how this process works, we need to understand how senders and receivers use TCP sequence numbers to label and keep track of data sent over TCP.

TCP sequence numbers

Every byte sent over a TCP connection has an ordered sequence number, assigned to it by its sender. Receiving machines use sequence numbers to shift the data that they receive back into its original order.

When two machines negotiate a TCP connection, each machine sends the other a random initial sequence number. This is the sequence number that the machine will assign to the first byte of data that it sends. Every subsequent byte is assigned the sequence number of the previous byte, plus 1. TCP segments contain TCP headers, which are metadata attached to the start of a segment. The sequence number of the first byte in a segment’s body is included in that segment’s TCP header.

Note that TCP connections are bi-directional, which means that data can be sent in both directions and that each machine in a TCP connection acts as both a sender and a receiver. Because of this, each machine must assign and manage its own, independent set of sequence numbers.

Acknowledging receipt of data

When a machine receives a TCP segment, it notifies the segment’s sender that it has been received. The receiver does this by sending an ACK (short for “acknowledge”) segment, containing the sequence number of the next byte that it expects to receive from the sender. The sender uses this information to infer that the receiver has successfully received all other bytes up to this number.

An ACK segment is denoted by the presence of the ACK flag and a corresponding acknowledgement number in the segment’s TCP headers. TCP has a total of 6 flags, including - as we will soon see - the RST (short for “reset”) flag that denotes a reset segment.

Sidenote - the TCP protocol also allows for selective ACKs, which are sent when a receiver has received some, but not all, segments in a range. For example “I’ve received bytes 1000-3000 and 4000-5000, but not 3001-3999”. For simplicity, we will ignore selective ACKs in our discussion of TCP reset attacks.

If a sender sends data but does not receive an ACK for it within a certain time interval, then the sender assumes that the data was lost and re-sends it, tagged with the same sequence numbers. This means that if the receiver receives the same bytes twice, it can trivially use sequence numbers to de-duplicate them without corrupting the stream. A receiver might receive duplicate data because an original segment arrived late, after it had been re-sent; or because an original segment arrived successfully but the corresponding ACK was lost on its way back to the sender.

So long as such duplicate data is relatively infrequent, the overhead that it causes is unproblematic. If all data eventually reaches its receiver, and the corresponding ACKs eventually reach their sender, the TCP connection is doing its job.

Choosing a sequence number for spoofed segment

As part of constructing a spoofed RST segment, an attacker needs to give their segment a sequence number. Receivers are happy to accept segments with non-sequential sequence numbers, and to take responsibility for stitching them back into the correct order. However, this tolerance is limited. If a receiver receives a segment with a sequence number that is “too” out of order then the receiver will discard the segment.

A successful TCP reset attack therefore requires a believable sequence number. But what counts as a believable sequence number? For most segments (although, as we will see, not RSTs), the answer is determined by the receiver’s TCP window size.

TCP window size

Imagine an ancient, early-1990s computer, connected to a modern gigabit fibre network. The lightning-quick network can feed data to the venerable computer at neckbreaking speed, much faster than the computer can handle it. This would not be helpful, because a TCP segment can’t be considered to have been received until the receiver has been able to process it.

Computers have a TCP buffer where newly-arrived data waits to be processed while the computer works through any data that arrived ahead of it. However, this buffer has a finite size. If the receiver is unable to keep up with the volume of data that the network is feeding it, the buffer will fill up. Once the buffer is completely full, the receiver will have no choice but to drop excess data on the floor. The receiver won’t send an ACK for the dropped data, and so the sender will have to re-send it once space opens up in the receiver’s buffer. It doesn’t matter how fast a network can send data if the receiver can’t keep up.

Imagine also an over-zealous friend who mails you a torrent of letters faster than you can read them. You have some amount of buffer space inside your mailbox, but once your mailbox fills up any overflow letters will spill out onto the floor and be eaten by foxes and other critters. Your friend will have to re-send the now-digested letters once you’ve had time to retrieve their earlier missives. Sending too many letters or too much data when the recipient is unable to process it is a pure waste of energy and bandwidth.

How much data is too much? How does a sender know when to send more data and when to hold back? This is where the TCP window size comes in. A receiver’s window size is the maximum number of unacknowledged bytes that a sender may have in flight to it at any one time. Suppose that a receiver advertises a window size of 100,000 (we’ll see how it broadcasts this value shortly), and so a sender fires off 100,000 bytes. Let’s say that by the time the sender has sent the 100,000th byte, the receiver has sent ACKs for the first 10,000 of those bytes. This means that there are 90,000 bytes still un-acked. Since the window size is 100,000, this leaves 10,000 more bytes that the sender can send before it has to wait for more ACKs. After sending 10,000 extra bytes, if there have been no further ACKs then the sender will have hit the limit of 100,000 un-acknowledged bytes. The sender will therefore have to wait and stop sending data (apart from re-sending data that it believes may be lost) until it receives some ACKs.

Each side of a TCP connection informs the other of its window size during the initial handshake that is performed when the connection is opened. Window sizes may also be adjusted dynamically during a connection. A computer with a large TCP buffer might declare a large window size in order to maximize throughput. This allows a machine communicating with it to continuously shovel data into the TCP connection, without having to pause and wait for any of it to be acknowledged. By contrast, a computer with a small TCP buffer might be forced to declare a small window size. Senders may sometimes fill up the window and be forced to wait until some of their segments have been acknowledged before continuing. This sacrifices some amount of throughput, but is necessary in order to prevent the receiver’s TCP buffer from overflowing.

The TCP window size is a hard limit on the amount of unacknowledged data that may be in-flight. We can use it to calculate the maximum possible sequence number (which I’m calling max_seq_no in the below equation) that a sender could have sent at a given time:

max_seq_no = max_acked_seq_no + window_size

max_acked_seq_no is the maximum sequence number that the receiver has sent an ACK for. It is the maximum sequence number that the sender knows that the receiver has received successfully. Since the sender is only allowed to have window_size unacknowledged bytes in-flight, the maximum sequence number that it can send is max_acked_seq_no + window_size.

Because of this, the TCP specification decrees that the receiver should ignore any data that it receives with sequence numbers outside its acceptable window. For example, if a receiver has acknowledged all bytes up to 15,000, and its window size is 30,000, then the receiver will accept any data with a sequence number between 15,000 and (15,000 + 30,000 = 45,000). By contrast, the receiver will completely ignore data with a sequence number outside this range. If a segment contains some data that is within its window, and some that is outside, then the data inside the window will be accepted and acknowledged, but the data outside it will be dropped. Note that we are still ignoring the possibility of selective ACKs, which we touched on briefly at the start of this post.

For most TCP segments, this rule gives the range of acceptable sequence numbers. However, as previously noted, the restrictions on RST segments are even stricter than those for normal, data-transmission, segments. As we will soon see, this is in order to make a type of TCP reset attack called a blind TCP reset attack more difficult.

Acceptable sequence numbers for RST segments

Normal segments are accepted if they have a sequence number anywhere between the next expected sequence number and that number plus the window size. However, RST packets are only accepted if they have a sequence number exactly equal to the next expected sequence number. Consider once again our previous example, in which the receiver has sent an acknowledgement number of 15,000. In order to be accepted, a RST packet must have a sequence number of exactly 15,000. If the receiver receives a RST segment with a sequence number that is not exactly 15,000, it will not accept it.

If the sequence number is completely out of range then the receiver ignores the segment entirely. If, however, it is within the window of expected sequence numbers, then the receiver sends back a “challenge ACK”. This is a segment which tells the sender that the RST segment had the wrong sequence number. It also tells the sender actual sequence number that the receiver was expecting. The sender can use the information in the challenge ACK to re-construct and re-send its RST.

Before 2010, the TCP protocol did not impose these additional restrictions on RST segments. RST segments were accepted or rejected according to the same rules as any other segment. However, this made blind TCP reset attacks too easy.

Blind TCP reset attacks

If an attacker is able to intercept the traffic being exchanged by their victims, the attacker can read the sequence and acknowledgment numbers on their victims’ TCP packets. They can use this information to decide what sequence numbers they should give their spoofed RST segments. By contrast, if the attacker cannot intercept their victims’ traffic then they will not know what sequence numbers they should insert. However, they can still blast out as many RST segments with as many different sequence numbers as possible and hope that one of them turns out to be correct. This is known as a blind TCP reset attack.

As we have already noted, in the original version of the TCP protocol an attacker only had to guess a RST sequence number somewhere within the receiver’s TCP window. A paper called “Slipping in the Window” showed that this made a successful blind attack too easy, since the attacker only needed to send a few tens of thousands of segments in order to be almost assured of success. To counter this, the rules for when a receiver should accept a RST segment were changed to the more restrictive criterion described above. With the new rules in force, blind TCP reset attacks require sending out millions of segments, making them all-but intractable. See RFC-5963 for more details.

Executing a TCP reset attack against ourselves

NOTE: I’ve tested this process on OSX, but have received several reports of it not working as intended on Linux.

We now know everything about executing a TCP reset attack. An attacker has to:

- Watch (or sniff) the network traffic being exchanged between our two victims

- Sniff a TCP segment with the

ACKflag enabled and read its acknowledgement number - Craft a spoofed TCP segment with the

RSTflag enabled, and a sequence number equal to the acknowledgement number of the intercepted segment (note that this assumes that data is exchanged over the connection slowly, and so our choice of sequence number does not quickly go out of date. We can fire off multipleRSTsegments with a range of sequence numbers if we want to increase our chance of success) - Send the spoofed segments to one or both of our victims, hopefully causing them to terminate their TCP connection

To practice, let’s execute a TCP attack against ourselves using a single computer talking to itself through localhost. To do this we need to:

- Set up a TCP connection between two terminal windows

- Write an attack program that sniffs the traffic

- Modify the attack program to craft and send spoofed

RSTsegments

Let’s begin.

1. Set up a TCP connection between two terminal windows

We set up our TCP connection using a tool called netcat, which comes pre-installed on many operating systems. Any other TCP client would do the job too. In our first terminal window we run:

nc -nvl 8000

This command starts a TCP server on your local machine, listening on port 8000. In our second terminal window we run:

nc 127.0.0.1 8000

This command attempts to make a TCP connection with the machine at IP address 127.0.0.1 on port 8000. These two terminal windows should now have a TCP connection established between them. Try typing some words into one window - the data should be sent over the TCP connection and appear in the other window.

2. Sniff the traffic

We write an attack program to sniff our connection’s traffic using scapy, a popular Python networking library. This program uses scapy read the data exchanged between our two terminal windows, despite not being part of the connection.

The code is in my GitHub repo. It sniffs traffic on our connection and prints it to the terminal. The core of the code is the call to scapy’s sniff method at the bottom of the file:

t = sniff(

iface='lo0',

lfilter=is_packet_tcp_client_to_server(localhost_ip, localhost_server_port, localhost_ip),

prn=log_packet,

count=50)

This snippet tells scapy to sniff packets on the lo0 interface, and to log details about all packets that are part of our TCP connection. The parameters are:

iface- tellsscapyto listen on thelo0, or localhost, network interfacelfilter- a filter function that tellsscapyto ignore all packets that aren’t part of a connection that is between two localhost IPs and is on our server’s port. This filtering is necessary because there are many other programs running on our machine that use thelo0interface. We want to ignore any packets that aren’t part of our experiment.prn- a function through whichscapyshould run each packet that matches thelfilterfunction. The function in the example above simply logs the packet to the terminal. In the next step we will modify this function to also send ourRSTsegments.count- the number of packets we wantscapyto sniff before returning.

To test out this program, set up the TCP connection as in step 1. Clone my GitHub repo, follow the setup instructions, and run the program in a third terminal window. Type some text into one of the terminals in the TCP connection. You should see the program start to log information about the connection’s segments.

3. Send spoofed RST packets

With a connection established and a program able to sniff the TCP segments passing through it, all that remains is for us to modify our program to execute a TCP reset attack by sending spoofed RST segments. To do this, we modify the prn function (see parameter list above) that scapy calls on packets that match our lfilter function. In the modified version of this function, instead of simply logging a matching packet, we inspect the packet, pull off the necessary parameters, and use those parameters to construct and send a RST segment.

For example, suppose we intercept a segment going from (src_ip, src_port) to (dst_ip, dst_port). It has the ACK flag set, and an acknowledgement number of 100,000. In order to craft and send our segment we:

- Switch the destination and source IPs, as well as the destination and source ports. This is because our packet is a response to the intercepted packet. Our packet’s source should be the original packet’s destination, and vice-versa.

- Turn on the segment’s

RSTflag, since this is what indicates the the segment is aRST - Set the sequence number to be the exact acknowledgement number from the packet that we intercepted, since this is the next sequence number that the sender expects to receive

- Call

scapy’ssendmethod to send the segment to our victim, the source of our intercepted packet

To modify our previous program to do this, uncomment this line and comment out the line above it.

We are now ready to execute the attack in full. Set up the TCP connection as in step 1. Run the attack program from step 2 in a third terminal window. Then type some text into one of the terminals in the TCP connection. The terminal that you typed into should have its TCP connection abruptly and mystifyingly killed. The attack is complete!

Further work

- Continue to experiment with the attack apparatus. See what happens if you add or subtract 1 from the sequence number of the

RSTpacket. Convince yourself that it does indeed need to be exactly equal to theackvalue of the intercepted packet. - Download Wireshark and use it to listen on the

lo0interface while you execute the attack. This will allow you to see all the details of every TCP segment exchanged over the connection, including the spoofedRST. Use the filterip.src == 127.0.0.1 && ip.dst == 127.0.0.1 && tcp.port == 8000to filter out extraneous traffic from other programs. - Make the attack harder to execute by sending a continuous stream of data over the connection. This will make it harder for our script to choose the correct sequence number for its

RSTsegments, because by the time theRSTsegment arrives at our victim the victim may have received further legitimate data, increasing its expected next sequence number. To counter this effect we can fire off multipleRSTpackets, each with different sequence numbers.

In conclusion

The TCP reset attack is both deep and simple. Good luck with your experimentation, and please do let me know if you have any questions or comments.