Off-The-Record Messaging part 1: the problem with PGP

15 Feb 2022

“A dog ate my homework” becomes quite a credible excuse when you ostentatiously purchase twenty ferocious dogs.

This is a 4 part series about Off-The-Record Messaging (OTR), a cryptographic messaging protocol that protects its users’ communications even if they get hacked.

Index

- Part 1: the problem with PGP

- Part 2: deniability and forward secrecy

- Part 3: how OTR works

- Part 4: OTR’s key insights

0. Introduction

Suppose that you want to have a clandestine conversation with a friend in a park. If you secure any nearby shrubberies then you can be confident that no one will be able to eavesdrop on you. And unless you’re being secretly recorded or filmed you can be similarly confident that no one will be able to make a permanent, verifiable record of your conversation. This means that you and your friend can have a private, off-the-record exchange of views. Local parks - and the physical world in general - have reasonably strong and intuitive privacy settings.

However, in the cyberworld these settings get more complex. An internet eavesdropper can’t hide in the bushes, but they can hack your computer or intercept your traffic as it travels over a network. There’s no record of most real-world conversations apart from the other person’s word, but electronic messages create a papertrail, which can be both useful and incriminating. These differences between the fleshy and virtual realms don’t necessarily increase or decrease net privacy, but they do change the threats and vectors that security- and privacy-sensitive people within them need to consider.

For example, in the physical world a brief lapse in communication security usually has limited consequences. It might allow a snooper to overhear a single conversation, or a disgruntled confederate to loosely retell, without proof, the details of a past discussion. However, in the cyberworld, brief lapses can be catastrophic and the consequences can be even worse than merely exposing confidential information.

Suppose that, as happens all too often, an attacker steals a dump of electronic messages and the secret key needed to decrypt them. The attacker will be able to open and read the previously-secret messages. To make matters worse, they may also be able to exploit the messages’ encryption protocol to prove to the world that the stolen messages are real, preventing the victims from claiming that they are fakes that should be ignored. On top of all this, the attacker may even be able to use the compromised secret key to decrypt years worth of historical messages that were also encrypted using that same key.

Fortunately we can mitigate these problems. Getting hacked doesn’t have to reveal all of your historical messages, and it doesn’t have to inadvertently provide proof that stolen messages are real. There’s much more to cryptography than just encrypting and decrypting messages, and the details matter. For example:

- How do the sender and receiver authenticate each other’s identities?

- Where do encryption keys come from?

- What algorithms are used to encrypt and decrypt messages?

- What happens to keys once they’ve been used?

- Do the sender and receiver ever need to generate new keys? How often?

Off-The-Record Messaging (OTR) is a cryptographic protocol that aims to replicate the privacy properties of a casual, in-person conversation. Like most cryptographic protocols, the primary goal of OTR is to prevent an attacker from reading its messages. But on top of this it guarantees that if someone somehow does gain access to an OTR message then they won’t be able to prove that it is real, and they certainly won’t be able to decrypt and read reams of historical messages. Any fool with decades of experience in high-grade cryptography can design a communication protocol that is secure when things go right. OTR focuses on what happens when things go wrong.

OTR does all this using standard, off-the-shelf ciphers and algorithms, and its (relatively) simple genius is in how it arranges old tools in novel patterns. In order to understand the innovations of OTR we don’t need to pore over pages of mathematical proofs. Instead we have to think precisely about the system-level ways in which familiar primitives are chained together. OTR inspired the first version of the Signal Protocol, used by the secure messaging app Signal, and learning how OTR works will invigorate your own cryptographic imagination too.

0.1 About this long blog post/short book

This long blog post/short book is based on Borisov, Goldberg and Brewer 2004, the paper that first introduced OTR. It assumes very little prior knowledge of cryptography. It won’t hurt to have prior experience with concepts like public and private keys and cryptographic signatures, but don’t worry if you don’t, we’ll cover what you need to know. Whereas Borisov, Goldberg and Brewer had but 7 pages in an academic journal, we have as much space as we like in which to cover the background, clarify the details, and ponder the ways in which OTR intersects with the 2020 US Presidential Election.

1. Why use Off-The-Record Messaging?

Alice and Bob want to talk to each other online. However, their privacy is under threat from the evil Eve, who wants to find out what they are saying and manipulate the contents of their messages. Alice and Bob want to stop her and talk to each other securely. To do this, they need a cryptographic protocol.

The two most basic properties that Alice and Bob need from a protocol are confidentiality and authenticity. Confidentiality means that Alice and Bob’s messages stay private and that Eve cannot read them. Authenticity means that Alice and Bob can be confident that they are talking to the right person and that Eve cannot spoof fake messages.

However, these aren’t the only properties that they want. Suppose that Eve hacks into Alice and Bob’s computers and steals their cryptographic keys. Even in this disaster scenario, Alice and Bob would like to ensure that Eve can’t use their keys to read any past encrypted messages that she has intercepted. This property is called forward secrecy. They would also like to prevent Eve from being able to prove that any messages that she does somehow steal are genuine. It’s bad if Eve leaks their messages to the press, but it’s less bad if they can credibly deny that they are real. This property is called deniability.

The original OTR paper was provocatively titled “Off-the-Record Communication, or, Why Not To Use PGP”. PGP is a widely-used and simple cryptographic protocol that provides good confidentiality and authenticity, but not perfect foward secrecy or deniability. OTR aims to address these shortcomings.

Since OTR began life as a challenge to PGP, we’ll begin our study of OTR by analysing PGP’s strengths and weaknesses. Then, with a working understanding of PGP under our belts, we’ll see how OTR mitigates PGP’s problems.

1.1 PGP

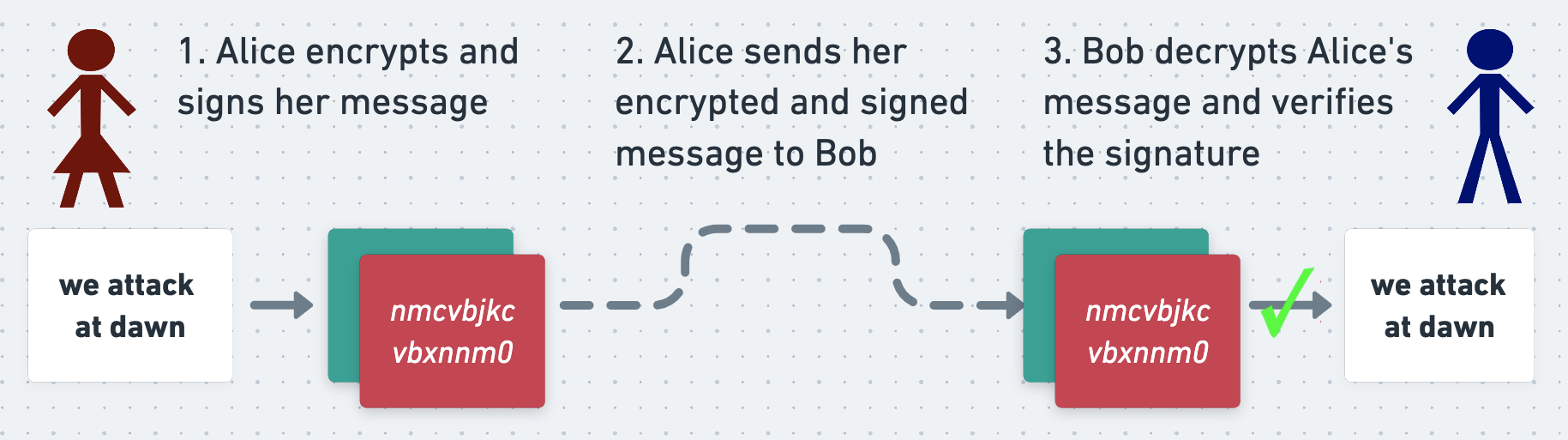

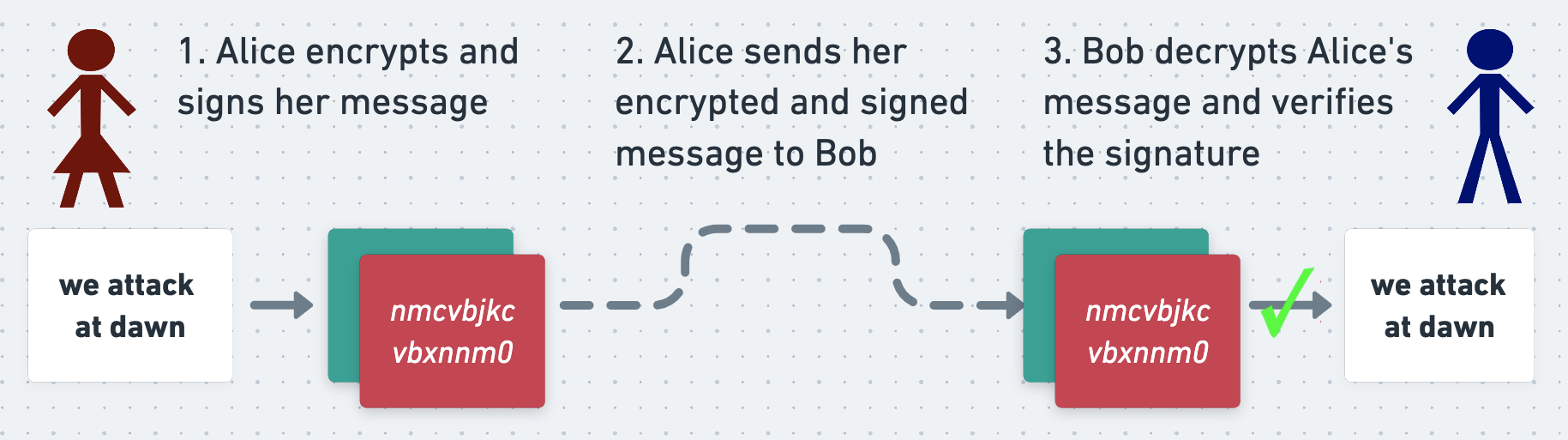

The PGP protocol can be used both to encrypt a message (which keeps it secret) and to sign it (which proves who wrote it). In short, when Alice wants to send a message to Bob, she first writes it in plaintext. She encrypts and signs it (more on which in a second) and sends the ciphertext and signature to Bob. When Bob receives Alice’s message he decrypts it, verifies the signature, and reads it.

If Eve intercepts Alice’s message on its way to Bob then she won’t be able to read it, and thanks to the signature she won’t be able to manipulate it without Bob noticing. This means that Alice and Bob can exchange secure messages over an insecure network.

Let’s look at how this all works.

Asymmetric encryption

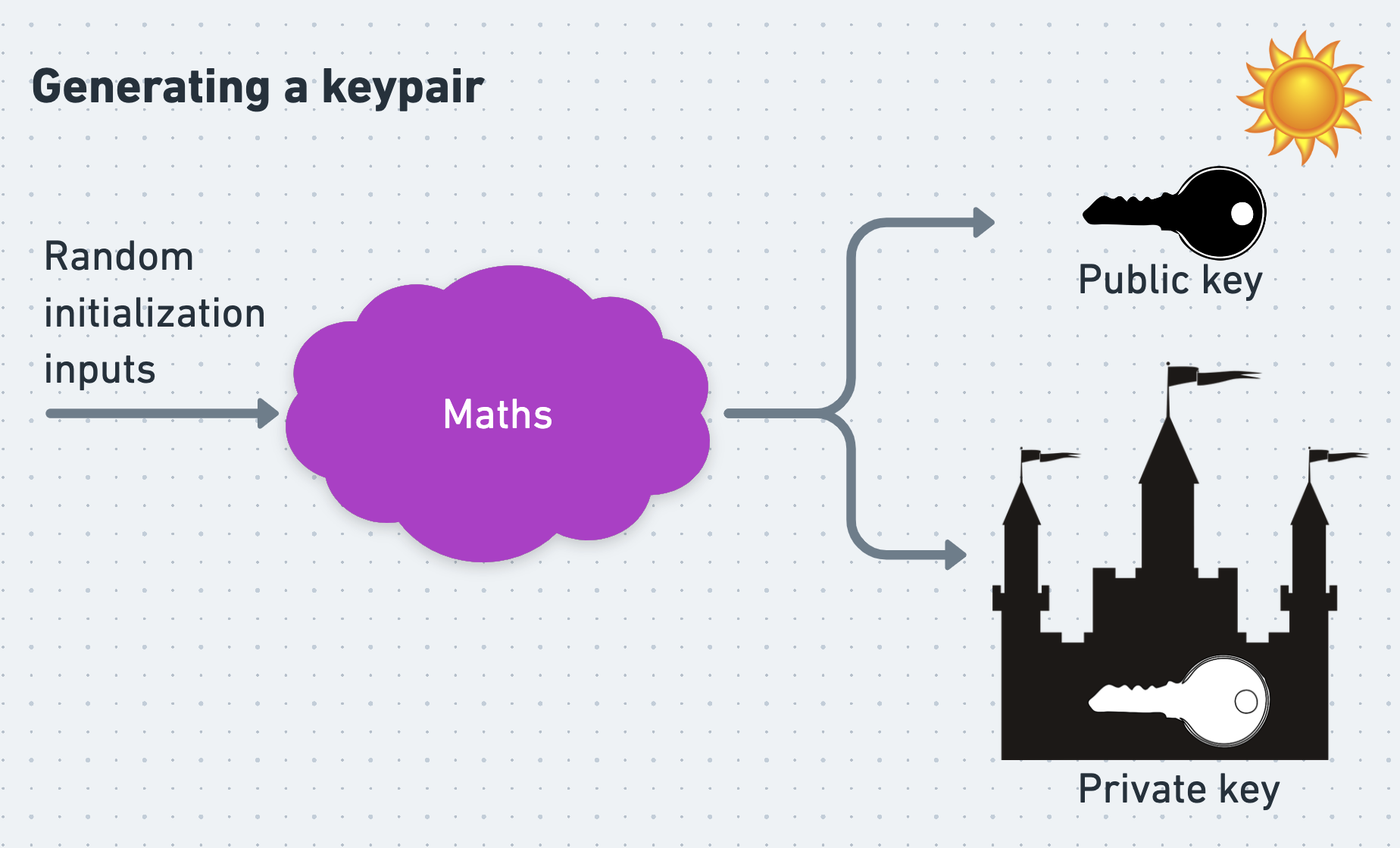

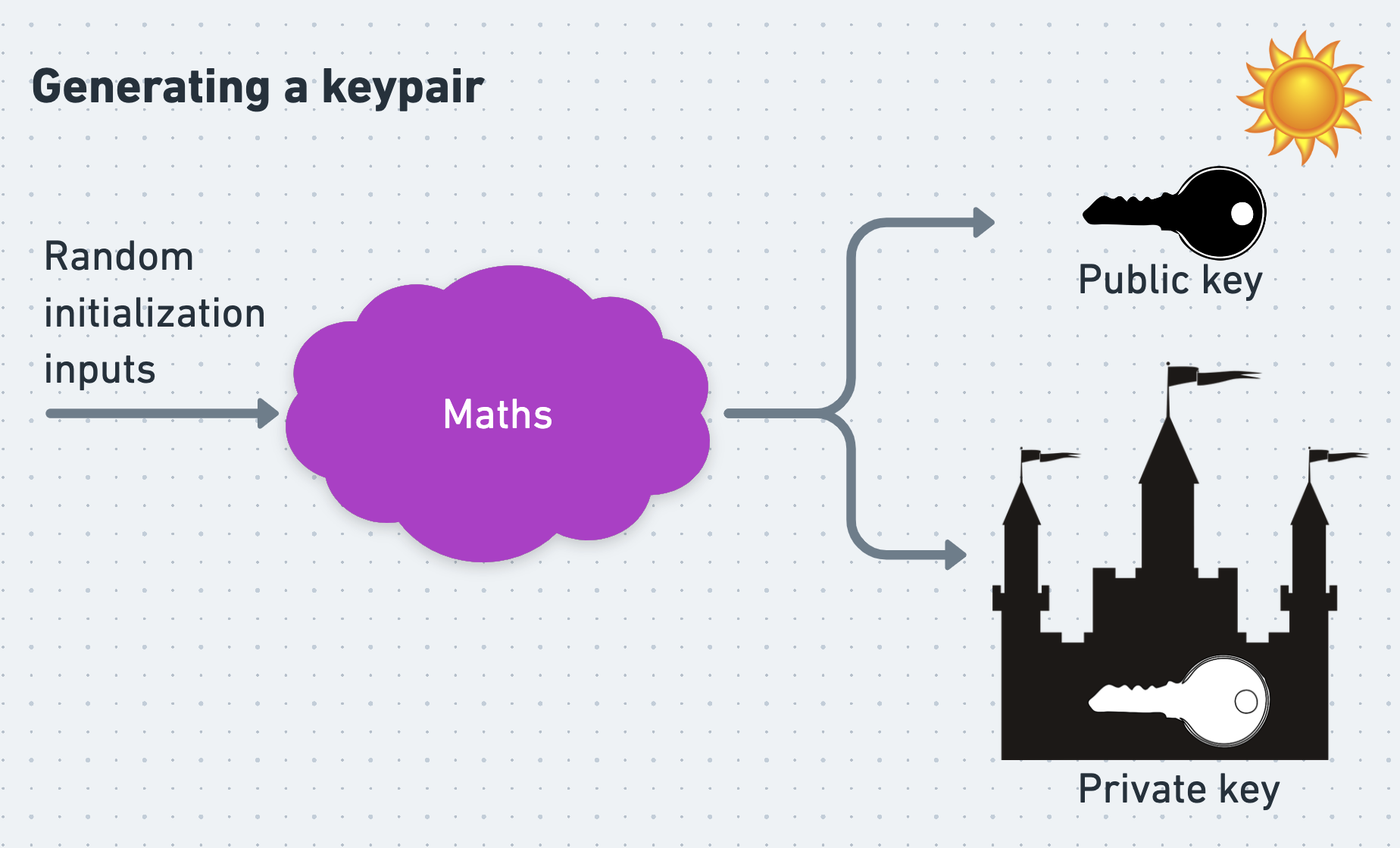

At its core PGP uses an asymmetric cipher, which is an encryption algorithm that uses one key for encryption and a different one for decryption. Before a person can receive PGP messages, they must first generate a pair of mathematically linked keys called a keypair. One of these keys is their private key, which they must keep secret and safe at all costs. The other is their public key, which they can safely publish and make available to anyone who wants it, even their enemies.

Distributing public keys reliably can be surprisingly difficult, and there is a deep literature on the ways in which they can be distributed, trusted, and un-trusted. I’ve written about these mechanisms elsewhere, but here we’ll assume that Alice and Bob are able to safely retrieve and trust each other’s public keys without problem.

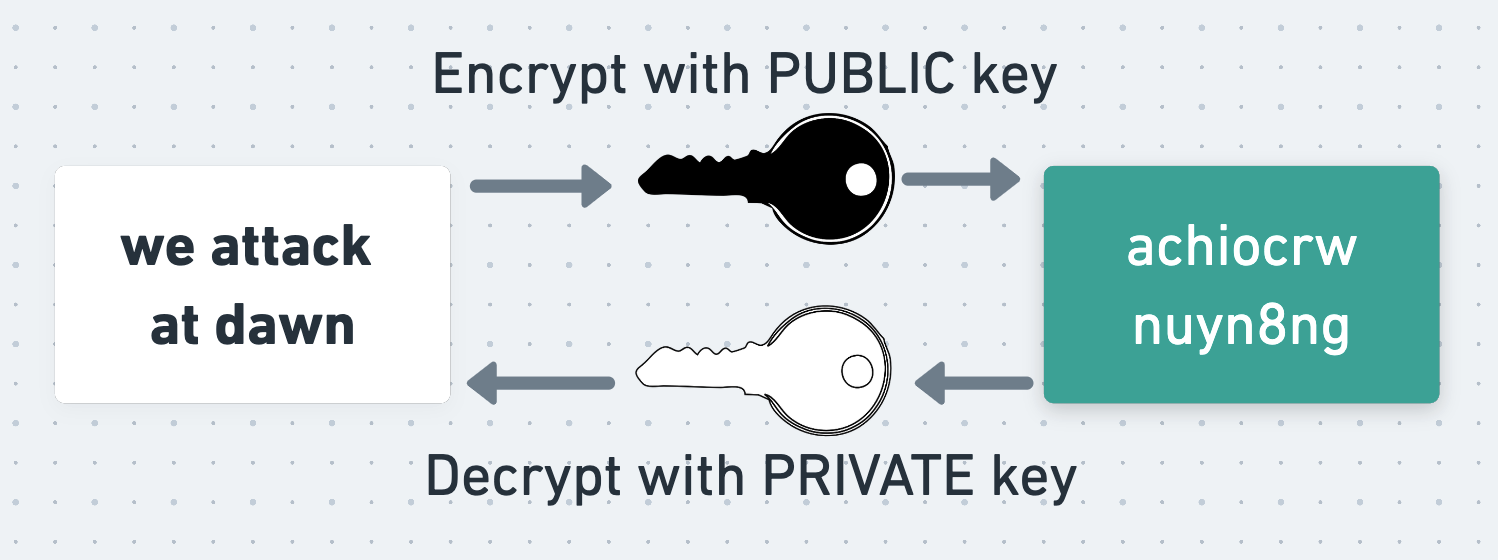

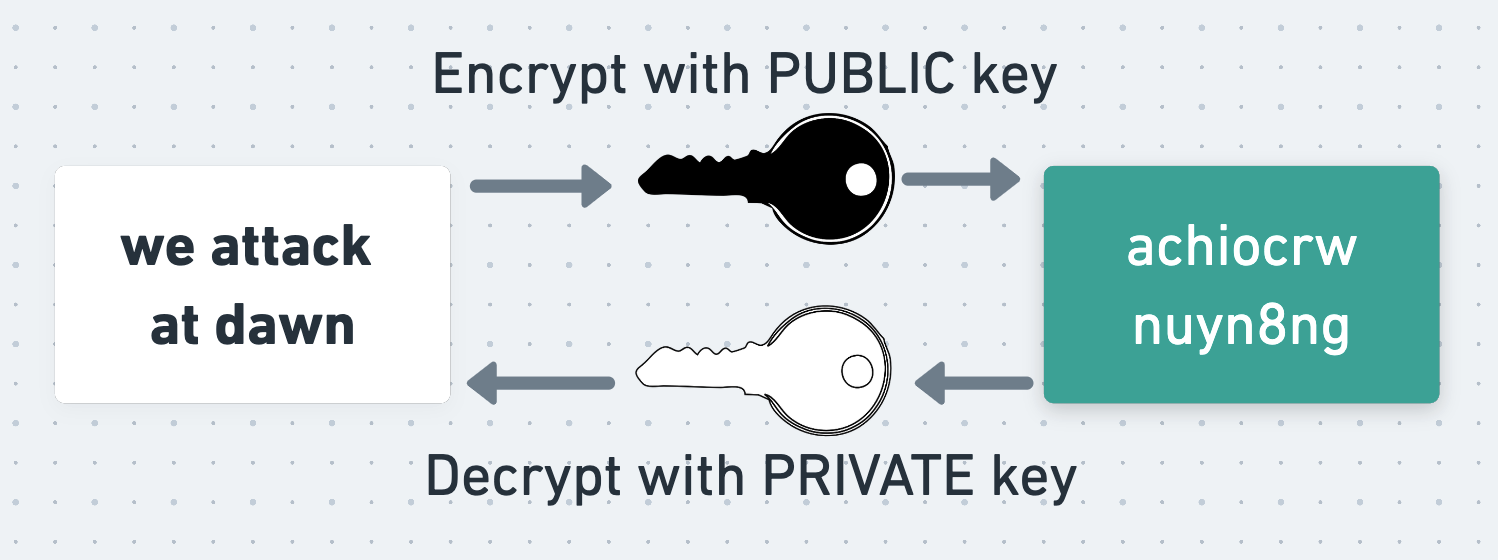

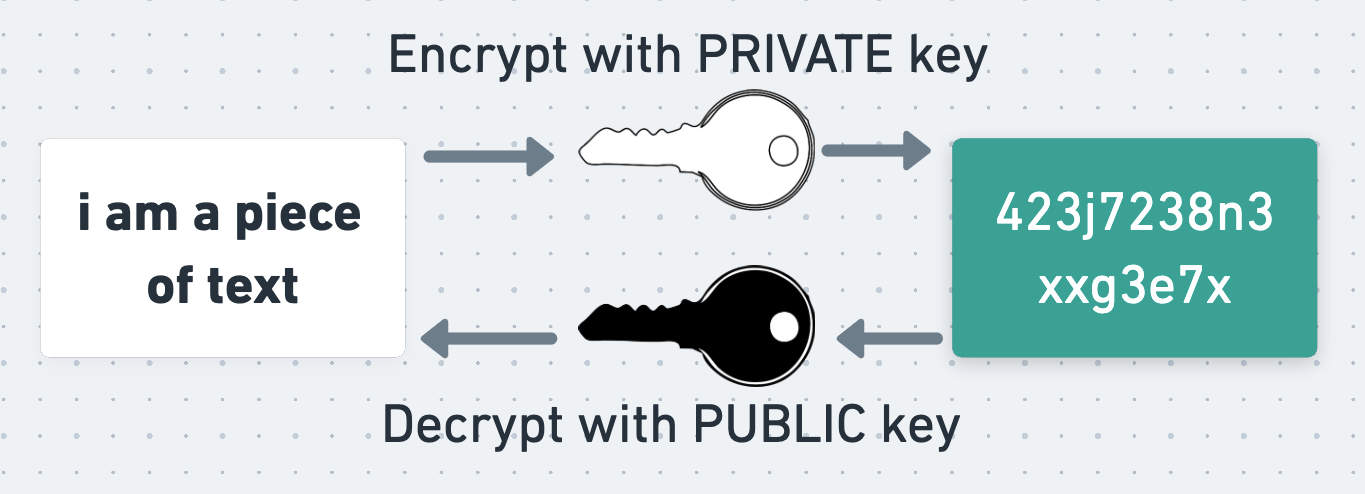

The critical property of asymmetric encryption is that data encrypted with a person’s public key can only be decrypted with their private key, and vice-versa.

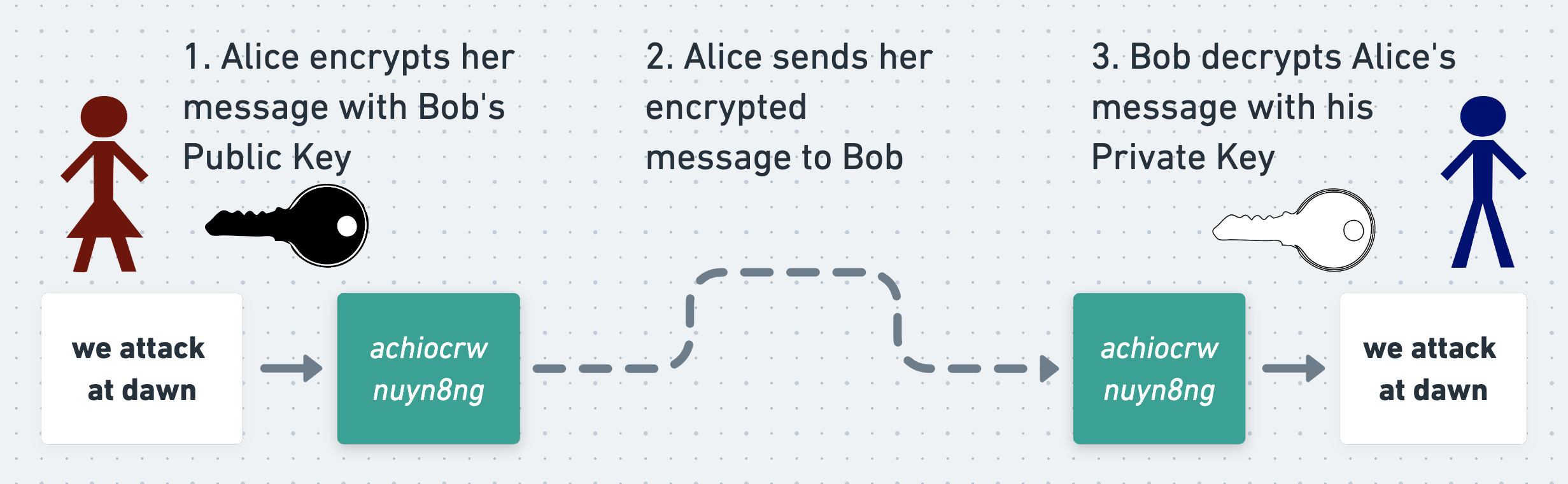

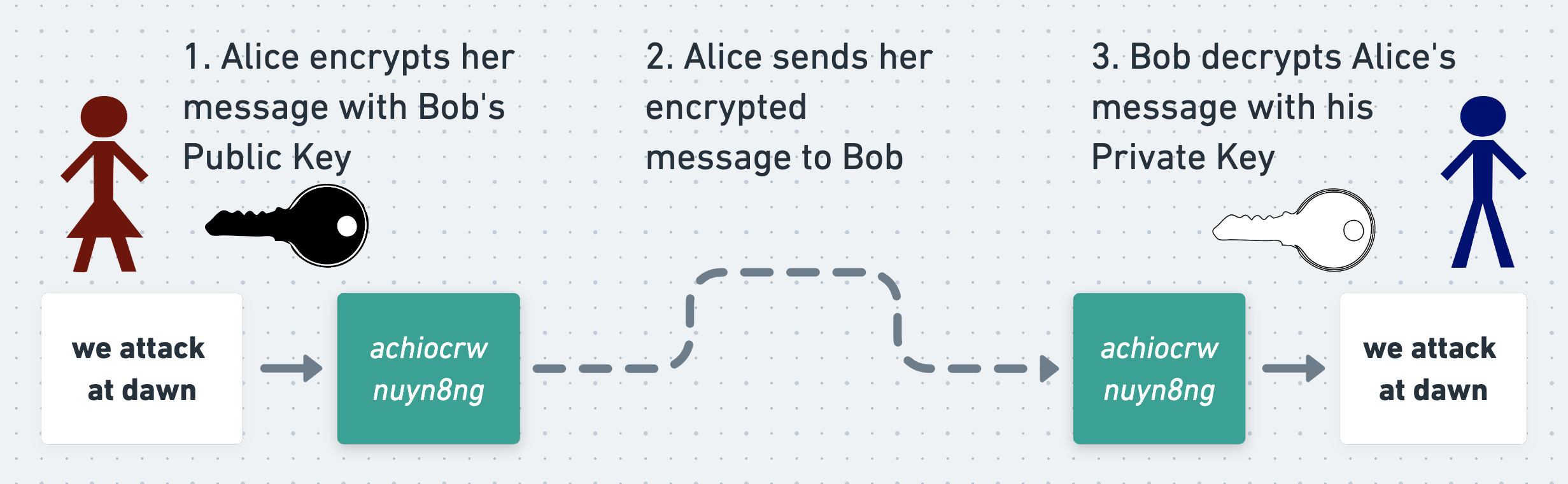

To see why this is so useful, suppose that Alice wants to send a secret message to Bob using an asymmetric cipher. The simplest way for her to do this is to directly encrypt her message using Bob’s public key (although PGP does something different, as we’ll see shortly). To do this, Alice retrieves Bob’s public key and encrypts her message with it. She sends the resulting ciphertext to Bob, and Bob uses his private key to decrypt and read it.

Since the message can only be decrypted using Bob’s private key, which only Bob knows, Alice and Bob can be confident that Eve can’t read their message even if she intercepts it.

Why is asymmetric encryption useful?

The big feature of asymmetric encryption is that it doesn’t require Alice and Bob to agree on a shared key ahead of time. All they have to do is distribute their public keys. They don’t care if Eve discovers them (so long as she doesn’t also discover their private keys), and indeed they fully expect her to.

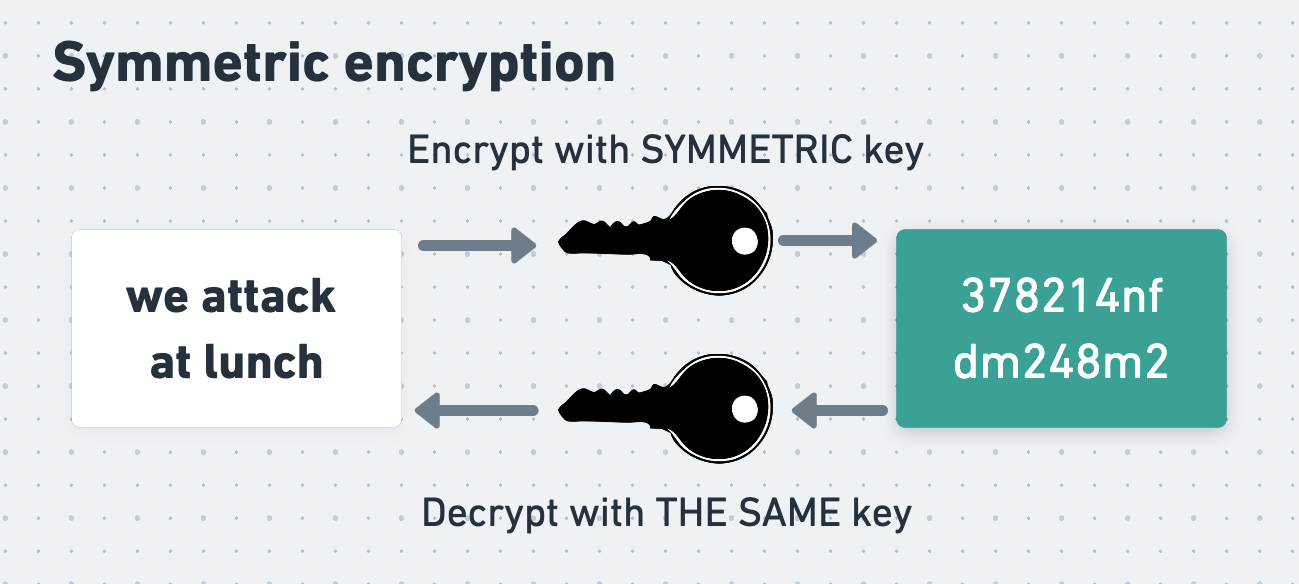

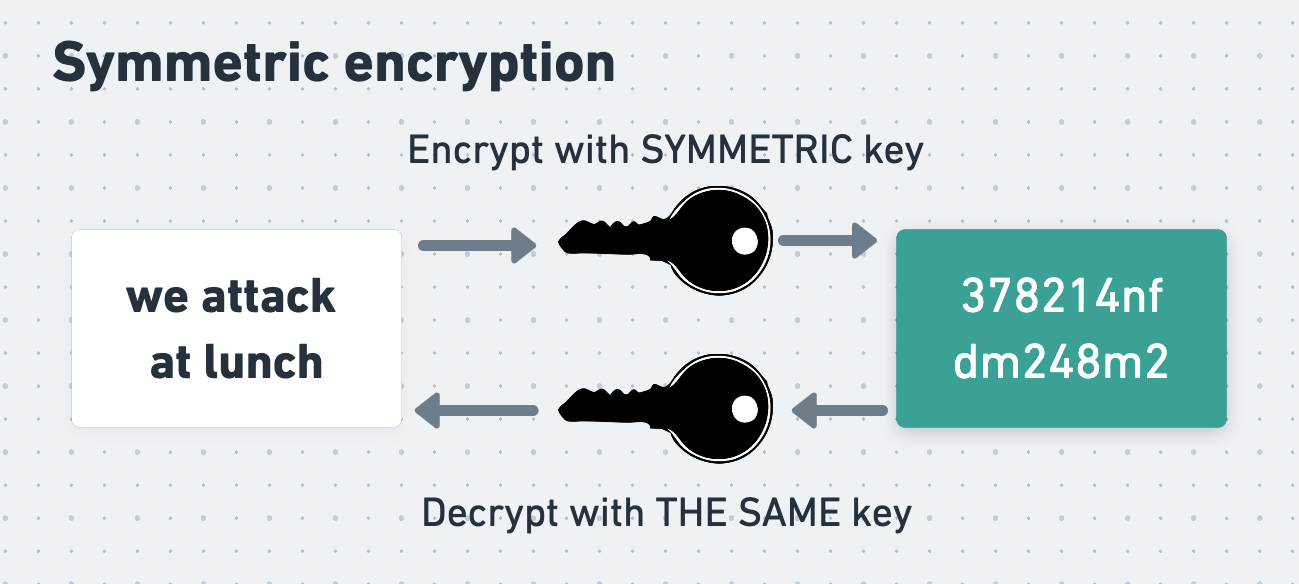

The opposite of asymmetric encryption is symmetric encryption. In symmetric encryption the same key is used for both encryption and decryption.

In order to exchange messages using symmetric encryption, Alice and Bob have to first agree on the symmetric key that they will use. This is tricky, since they can’t simply have one person generate a key and send it to the other. Eve might intercept the key and then use it to decrypt the messages that follow it. As we’ll see, there do exist plenty of ways for Alice and Bob to agree on a shared, symmetric key without Eve being able to discover it, but doing this does require care.

Nonetheless, neither family of algorithms is inherently more “secure” than the other, and an attacker who doesn’t know the relevant secret key will not be able to read a message that has been robustly encrypted with either type of algorithm.

How PGP uses asymmetric encryption

In fact, PGP uses both asymmetric and symmetric encryption. It does this because asymmetric encryption is slow, especially for long inputs. Using an asymmetric cipher to encrypt a long message in its entirety would be unacceptably time-consuming. By contrast, symmetric ciphers are much zippier. Alice and Bob would therefore prefer to do as much of their encryption and decryption as possible using a symmetric cipher instead of an asymmetric one. But how can they agree on a single, shared key to use with a symmetric cipher without Eve being able to see this key too?

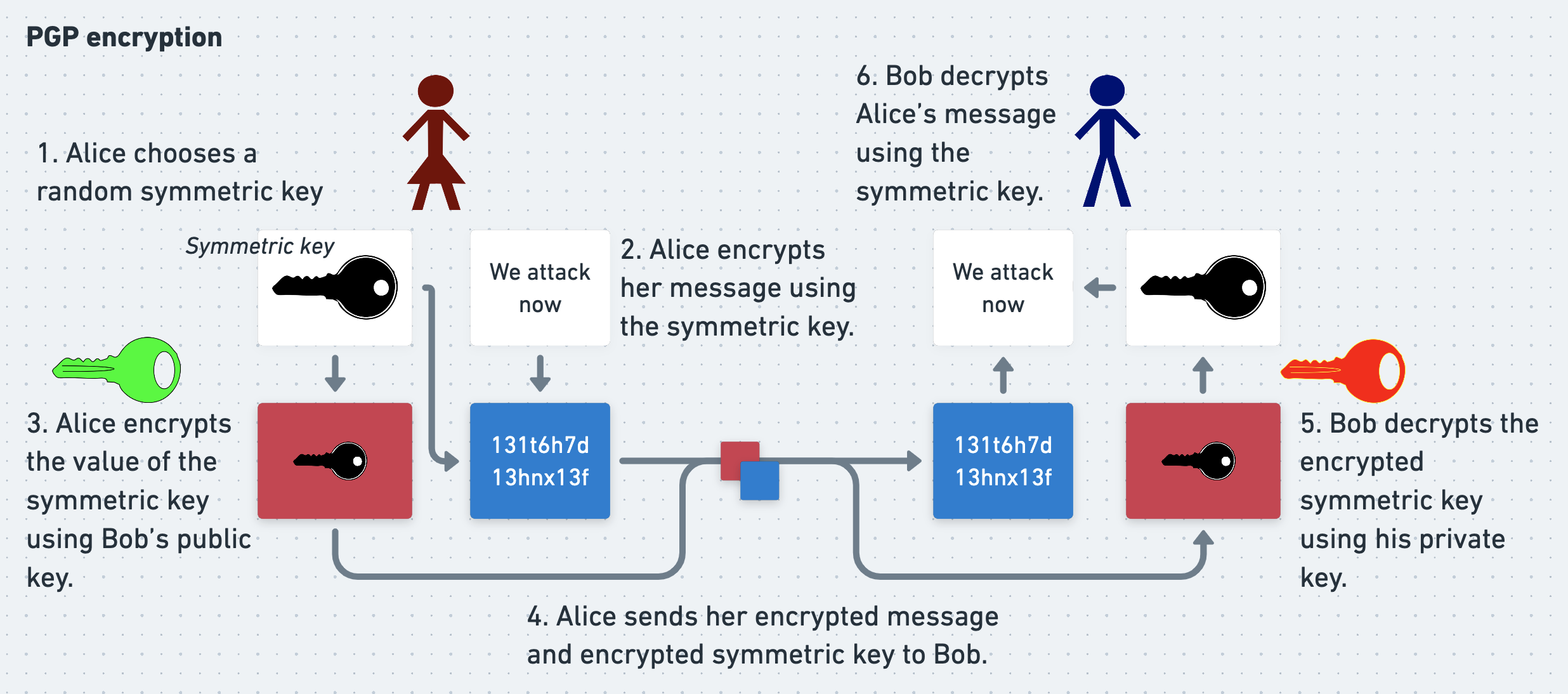

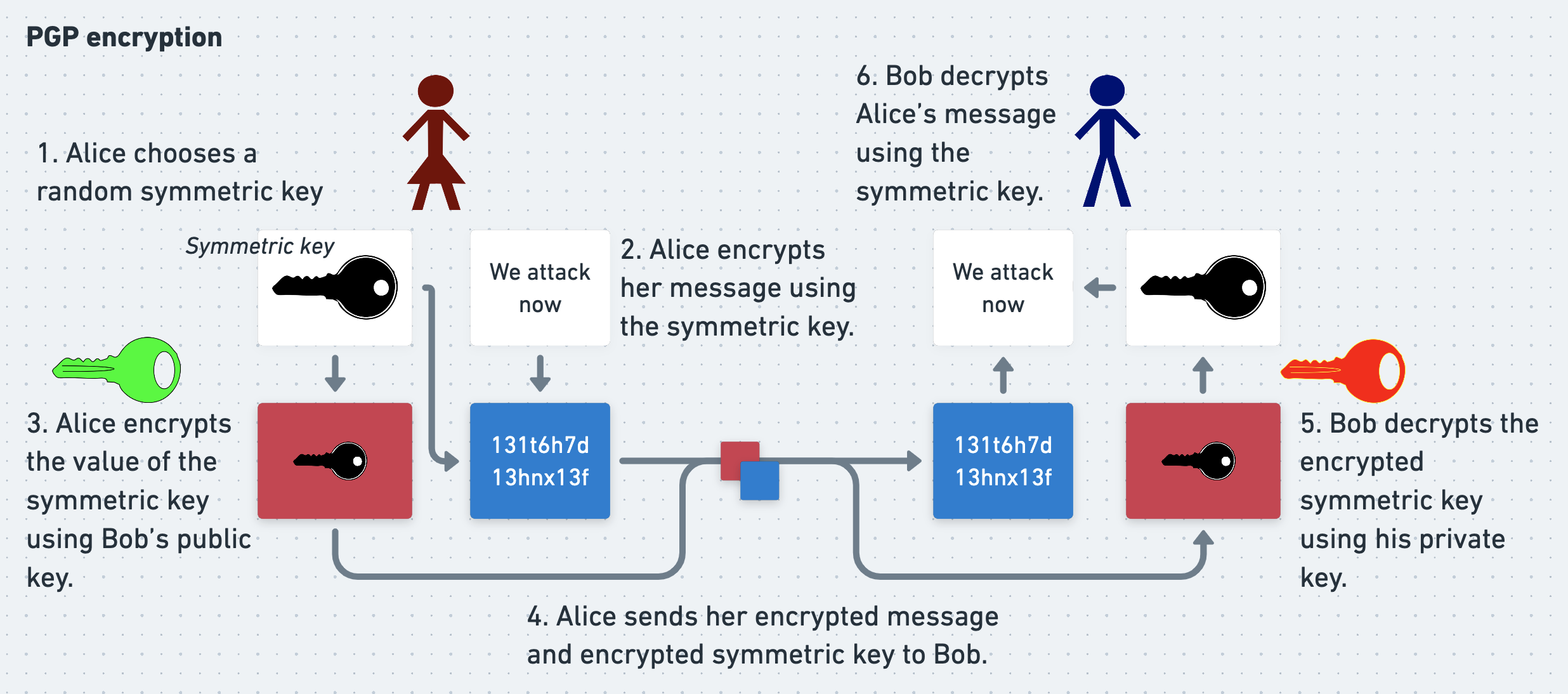

PGP gets the best of both worlds with a neat trick. In PGP, Alice doesn’t encrypt her entire message using an asymmetric cipher. Instead, she encrypts it using a symmetric cipher, with a random symmetric key that she generates called a session key.

To allow Bob to decrypt her message, Alice needs to send him the session key. She also needs to ensure that Eve can’t read the key. To achieve this, she encrypts the session key using Bob’s public key. Now Eve can’t recover the session key without Bob’s private key, which - all being well - only Bob knows. And since Eve can’t recover the session key, she also can’t decrypt Alice’s actual message, even if she intercepts every byte of traffic that Alice and Bob exchange. Alice can therefore confidently send both the symmetrically-encrypted message and asymmetrically-encrypted session key to Bob.

To read Alice’s message Bob reverses Alice’s process. He uses his private key to decrypt the symmetric session key, and then uses the session key to decrypt the actual message. With PGP Alice and Bob get the convenience of asymmetric cryptography with the speed of symmetric.

Cryptographic signatures

However, even though Bob is the only person who can read Alice’s message, at the moment he has no proof that the message really was written by Alice. As far as he’s concerned it could have been written and encrypted by Eve pretending to be Alice, or Eve could have intercepted and manipulated a real message from Alice. To prove to Bob that she wrote her message, Alice uses PGP to cryptographically sign it before sending it.

A cryptographic signature is a blob of data attached to a message that allows the recipient to prove to themselves who wrote the message. It also allows them to satisfy themselves that the message has not been tampered with. Signatures can be generated in several different ways, including the same kind of asymmetric cryptography that Alice and Bob just used to encrypt their messages.

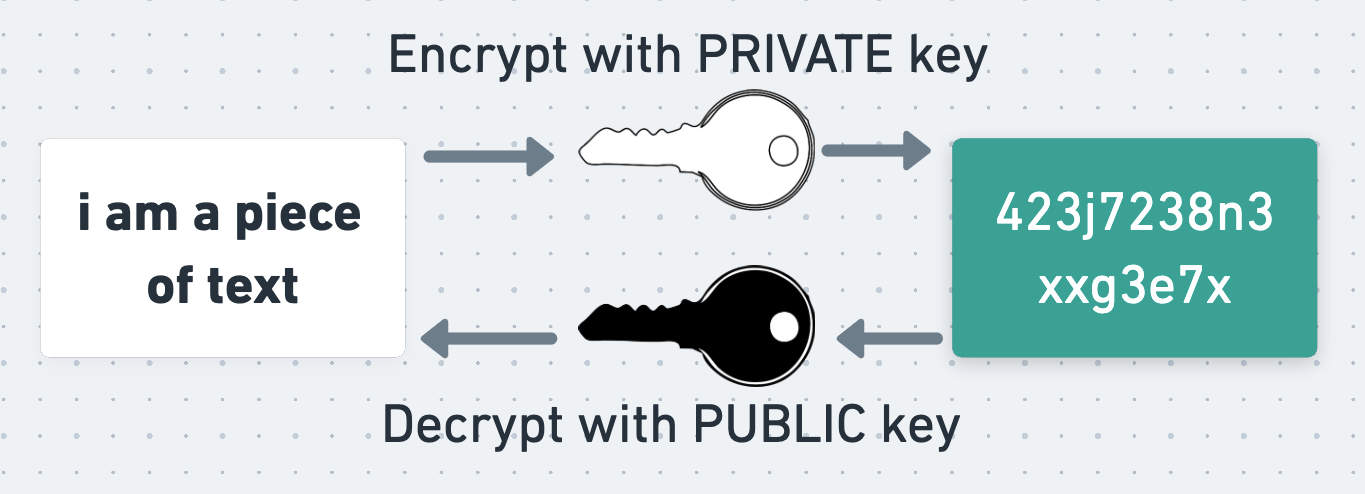

When encrypting and decrypting a message using asymmetric cryptography, Alice and Bob exploit the fact that a message encrypted using a public key can only be decrypted using the corresponding private key. To sign a message, they exploit the equivalent but inverse fact that a message encrypted with a private key can only be decrypted using the corresponding public key.

To produce a naive signature, Alice can take her encrypted message and encrypt it again using her private key. The result of this operation is the message’s signature. She can attach this signature to her encrypted message and send both it and the message to Bob.

This signature is useful because Bob can decrypt it using Alice’s public key, and verify that the result is equal to Alice’s encrypted message. This proves to Bob that the signature was produced using Alice’s private key, and therefore that the message was signed and written by Alice. He also knows that the message hasn’t been tampered with in transit, because if it had then the result of decrypting the signature would no longer equal the encrypted message. In order to mess with the message without being detected, Eve would need to update the signature too. However, since she doesn’t know Alice’s private key, she can’t generate a valid signature for her mutated message.

This is the principle underlying all types of cryptographic signature.

Cryptographic signatures in practice

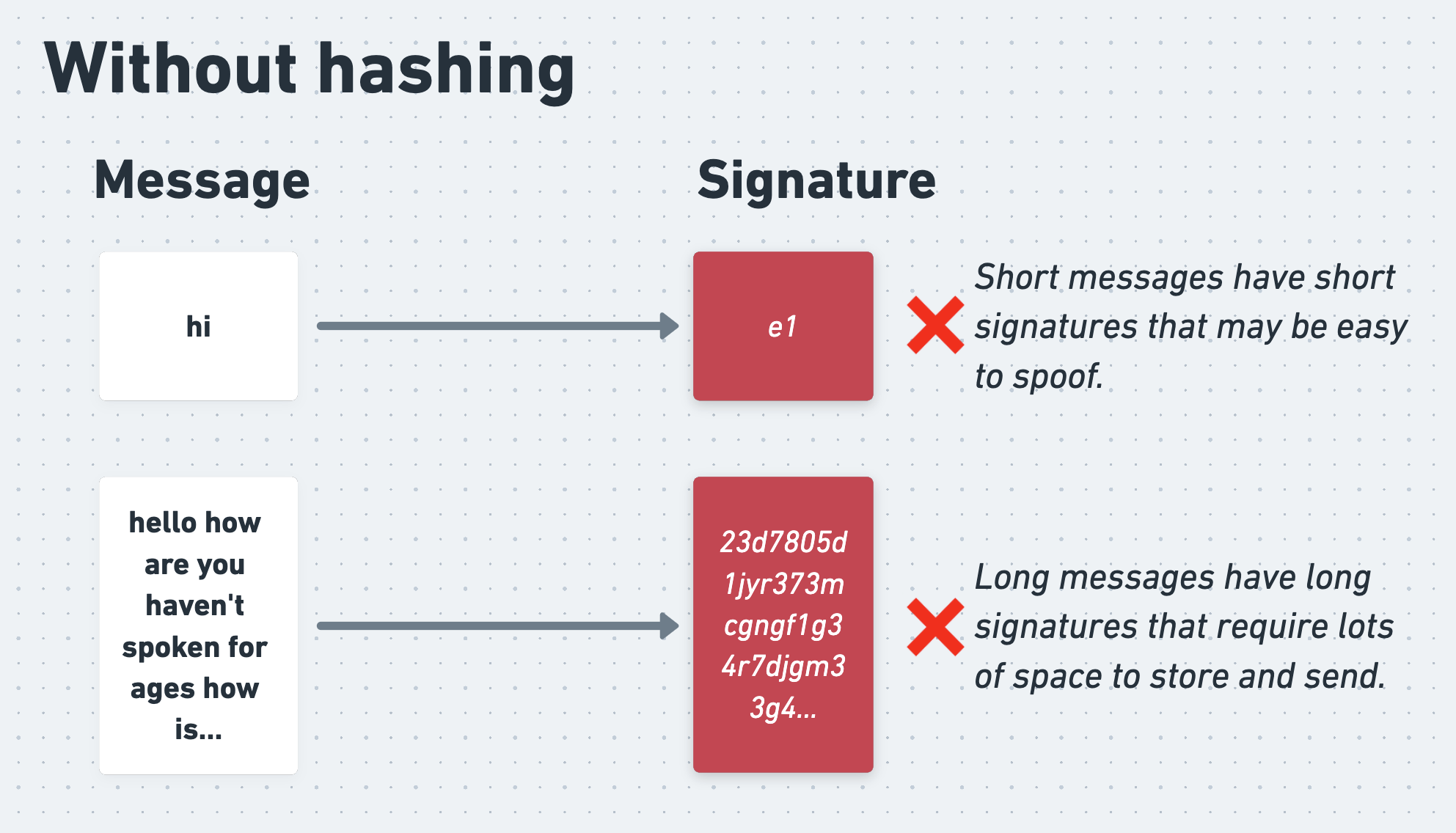

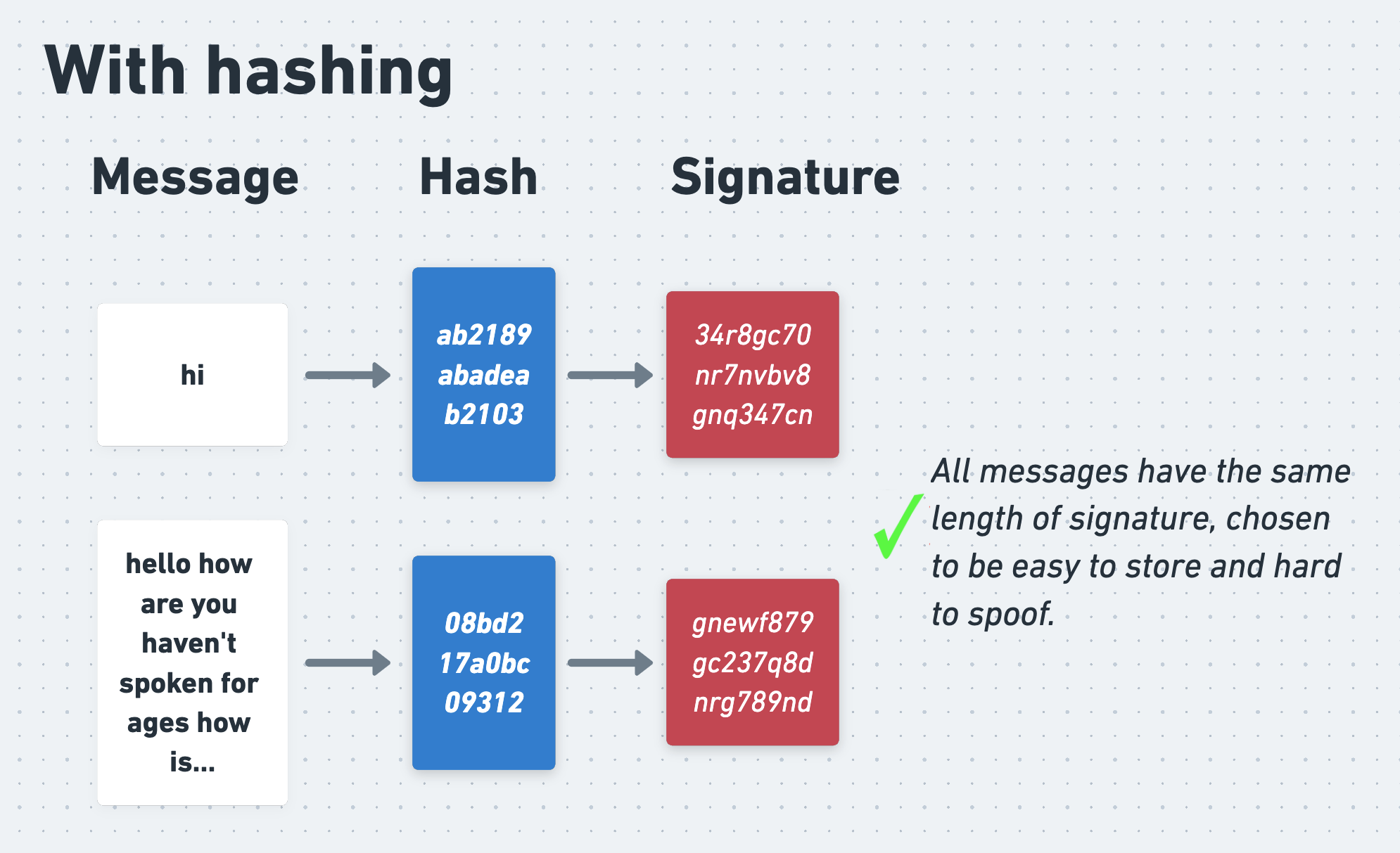

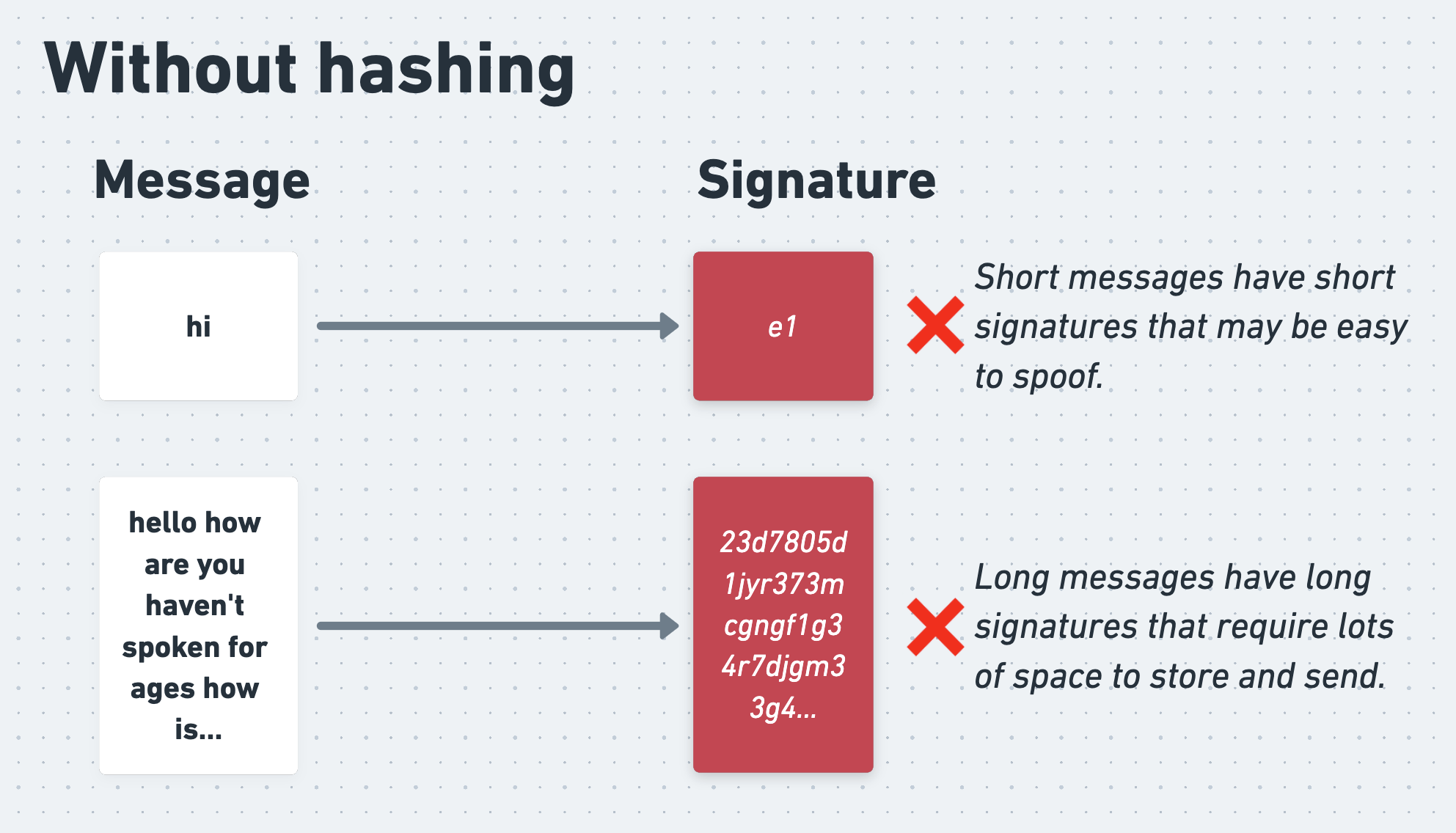

In practice, Alice doesn’t actually sign her encrypted message directly. This is because, as we know, asymmetric encryption is slow. On top of this, signing the entire message would produce a signature of the same length as the message, which would require unnecessary bandwidth to send. What’s more, short messages would produce short signatures, which could be easy for an attacker to forge, even without knowing Alice’s secret key.

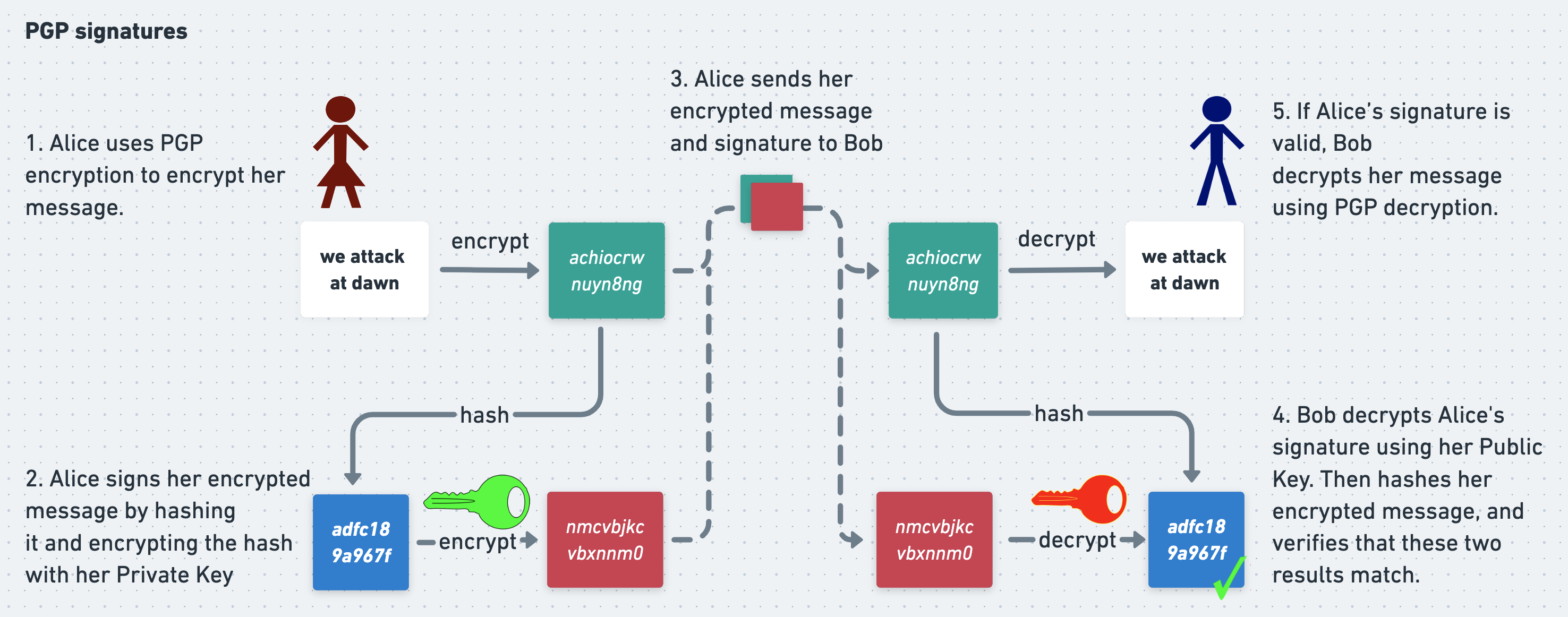

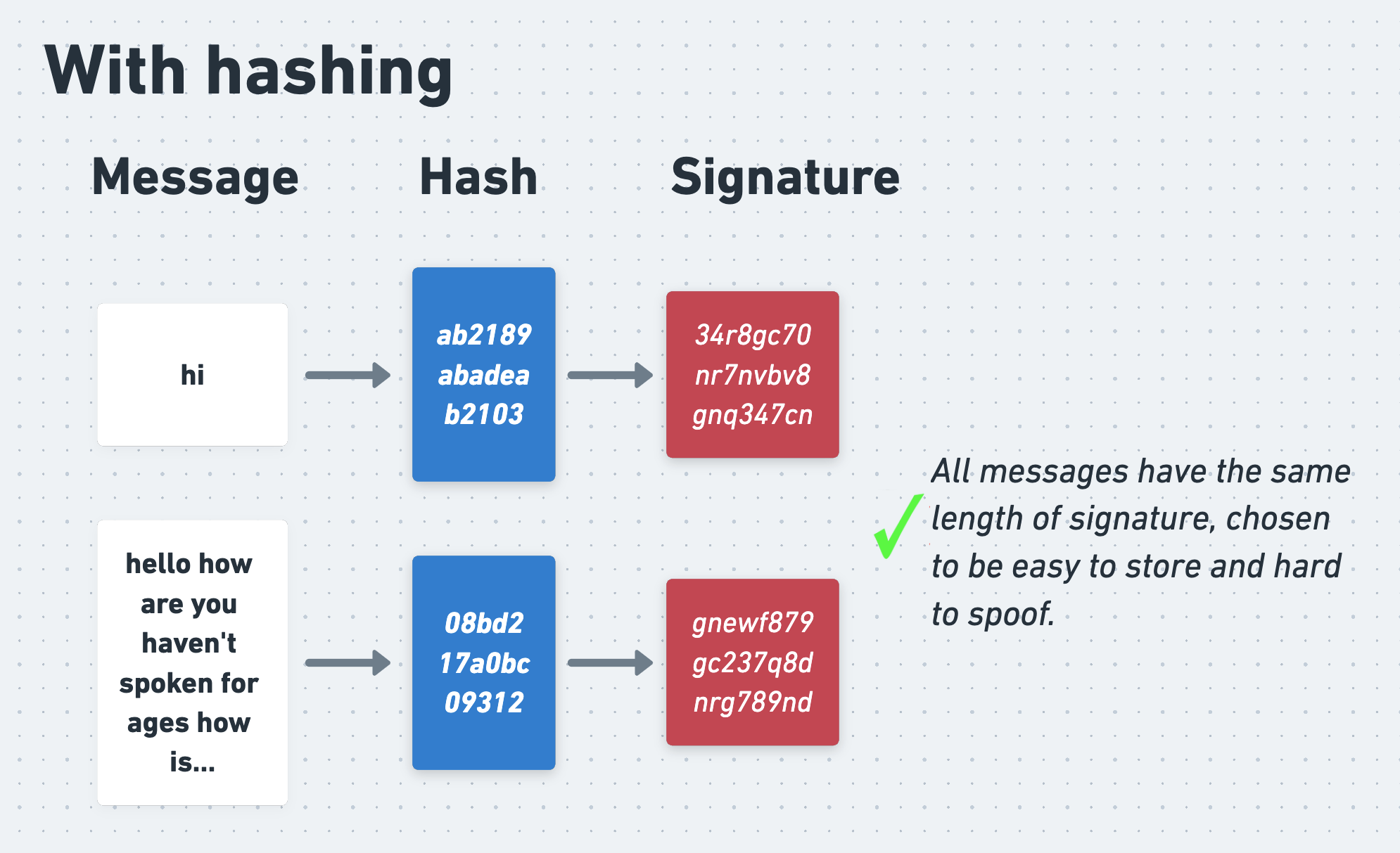

Alice therefore starts by passing her message through a hash function, which is an algorithm that produces a random-seeming but consistent and fixed-length output for a given input. She then signs the output of the hash function with her private key.

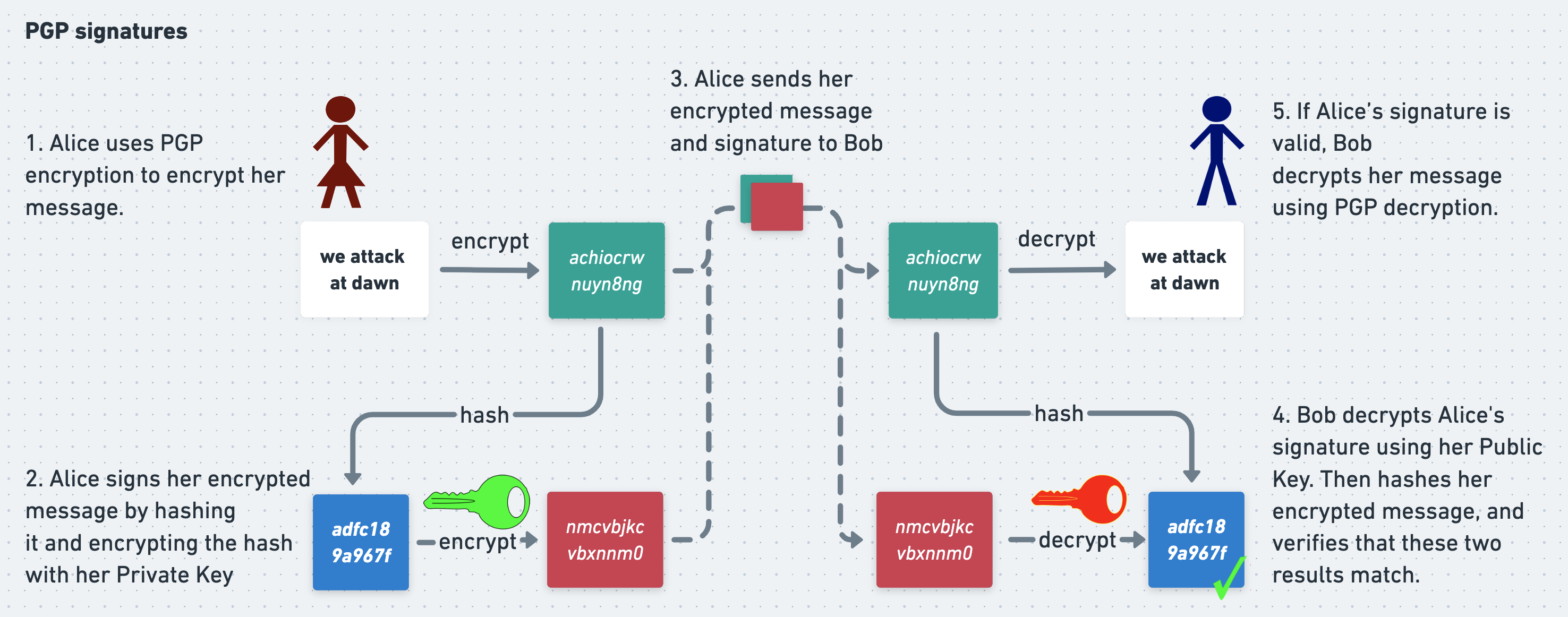

Putting this all together gives us the following picture:

When Bob receives Alice’s message and signature, he uses a hash function to verify the signature too. He decrypts Alice’s signature using her public key, but then instead of comparing the result to her message directly, he first hashes her message and compares the output to the decrypted signature. If they match then Bob can be confident that the message is authentic.

The problems with PGP

Encryption and signatures are how PGP gives Alice and Bob confidentiality and authenticity. We’ve seen how Eve can’t decrypt Alice’s messages because she doesn’t know Bob’s private key, and so she can’t decrypt the symmetric session key. She can’t spoof a fake message from Alice to Bob because she doesn’t know Alice’s private key, and so won’t be able to generate a valid signature. If everything goes perfectly, PGP works perfectly.

However, in the real world, we also have to plan for the times when everything does not go perfectly. This is where PGP falls down, and where OTR aims to improve on it. PGP relies heavily on private keys staying private. If a user’s private key is stolen (for example, if their computer is hacked and all their files stolen) then the security properties previously underpinned by it are blown apart. Suppose that Eve steals a copy of Bob’s private key and intercepts Alice’s message on its way to Bob. She’ll be able to decrypt the session keys that Alice encrypts using Bob’s public key, and then use them to decrypt Alice’s messages. If she steals a copy of Alice’s private key then she can use it to sign fake messages that Eve herself has written, making it look like these messages came from Alice.

All encryption is to some degree underpinned by the assumption that secret keys stay secret, and so we should expect any protocol to be severely damaged if this assumption is broken. But with PGP the fallout is worse than just leaking confidential messages. We know already that if Eve steals a private key then she can use it to decrypt any future PGP messages that she intercepts and that were encrypted using the corresponding public key. But suppose that Eve has been listening to Alice and Bob for months or years, patiently storing all of their encrypted traffic. Previously she had no way to read any of this traffic, but with access to Bob’s private key she can now decrypt all of their historical session keys and use them to decrypt all of their old, previously-secret messages.

But it gets even worse. Alice cryptographically signed all her PGP messages so that Bob could be confident that they were authentic. However, whilst generating a signature requires Alice’s private key, verifying it only requires her public key, which is typically freely available. This means that Eve can use Alice’s signatures to verify the authenticity of messages that she steals from Bob just as well as Bob can. If Eve gets access to Alice and Bob’s signed messages, she also gets access to a cryptographically verifiable transcript of their communications. This prevents Alice and Bob from credibly denying that the stolen messages are real. In a few sections’ time we’ll look at some real-world examples of how cryptographic signatures like this can cause serious problems for the victims of hacks.

PGP does give confidentiality and authenticity. But it’s brittle, and it isn’t robust to private key compromise. We’d ideally like an encryption protocol that better mitigates the consequences of a hack. In particular we’d like two extra properties. First, we’d like deniability, which is the ability for a user to credibly deny that they ever sent hacked messages. And second, we’d like forward secrecy, which is the property that if an attacker compromises a user’s private key then they are still unable to read past traffic that was encrypted using that keypair.

In part 2 of this series we’ll examine these two properties in detail and see why they are so desirable. Then in parts 3 and 4 we’ll look at how Off-The-Record-Messaging works and how it provides them.

Index

“A dog ate my homework” becomes quite a credible excuse when you ostentatiously purchase twenty ferocious dogs.

This is a 4 part series about Off-The-Record Messaging (OTR), a cryptographic messaging protocol that protects its users’ communications even if they get hacked.

Index

- Part 1: the problem with PGP

- Part 2: deniability and forward secrecy

- Part 3: how OTR works

- Part 4: OTR’s key insights

0. Introduction

Suppose that you want to have a clandestine conversation with a friend in a park. If you secure any nearby shrubberies then you can be confident that no one will be able to eavesdrop on you. And unless you’re being secretly recorded or filmed you can be similarly confident that no one will be able to make a permanent, verifiable record of your conversation. This means that you and your friend can have a private, off-the-record exchange of views. Local parks - and the physical world in general - have reasonably strong and intuitive privacy settings.

However, in the cyberworld these settings get more complex. An internet eavesdropper can’t hide in the bushes, but they can hack your computer or intercept your traffic as it travels over a network. There’s no record of most real-world conversations apart from the other person’s word, but electronic messages create a papertrail, which can be both useful and incriminating. These differences between the fleshy and virtual realms don’t necessarily increase or decrease net privacy, but they do change the threats and vectors that security- and privacy-sensitive people within them need to consider.

For example, in the physical world a brief lapse in communication security usually has limited consequences. It might allow a snooper to overhear a single conversation, or a disgruntled confederate to loosely retell, without proof, the details of a past discussion. However, in the cyberworld, brief lapses can be catastrophic and the consequences can be even worse than merely exposing confidential information.

Suppose that, as happens all too often, an attacker steals a dump of electronic messages and the secret key needed to decrypt them. The attacker will be able to open and read the previously-secret messages. To make matters worse, they may also be able to exploit the messages’ encryption protocol to prove to the world that the stolen messages are real, preventing the victims from claiming that they are fakes that should be ignored. On top of all this, the attacker may even be able to use the compromised secret key to decrypt years worth of historical messages that were also encrypted using that same key.

Fortunately we can mitigate these problems. Getting hacked doesn’t have to reveal all of your historical messages, and it doesn’t have to inadvertently provide proof that stolen messages are real. There’s much more to cryptography than just encrypting and decrypting messages, and the details matter. For example:

- How do the sender and receiver authenticate each other’s identities?

- Where do encryption keys come from?

- What algorithms are used to encrypt and decrypt messages?

- What happens to keys once they’ve been used?

- Do the sender and receiver ever need to generate new keys? How often?

Off-The-Record Messaging (OTR) is a cryptographic protocol that aims to replicate the privacy properties of a casual, in-person conversation. Like most cryptographic protocols, the primary goal of OTR is to prevent an attacker from reading its messages. But on top of this it guarantees that if someone somehow does gain access to an OTR message then they won’t be able to prove that it is real, and they certainly won’t be able to decrypt and read reams of historical messages. Any fool with decades of experience in high-grade cryptography can design a communication protocol that is secure when things go right. OTR focuses on what happens when things go wrong.

OTR does all this using standard, off-the-shelf ciphers and algorithms, and its (relatively) simple genius is in how it arranges old tools in novel patterns. In order to understand the innovations of OTR we don’t need to pore over pages of mathematical proofs. Instead we have to think precisely about the system-level ways in which familiar primitives are chained together. OTR inspired the first version of the Signal Protocol, used by the secure messaging app Signal, and learning how OTR works will invigorate your own cryptographic imagination too.

0.1 About this long blog post/short book

This long blog post/short book is based on Borisov, Goldberg and Brewer 2004, the paper that first introduced OTR. It assumes very little prior knowledge of cryptography. It won’t hurt to have prior experience with concepts like public and private keys and cryptographic signatures, but don’t worry if you don’t, we’ll cover what you need to know. Whereas Borisov, Goldberg and Brewer had but 7 pages in an academic journal, we have as much space as we like in which to cover the background, clarify the details, and ponder the ways in which OTR intersects with the 2020 US Presidential Election.

1. Why use Off-The-Record Messaging?

Alice and Bob want to talk to each other online. However, their privacy is under threat from the evil Eve, who wants to find out what they are saying and manipulate the contents of their messages. Alice and Bob want to stop her and talk to each other securely. To do this, they need a cryptographic protocol.

The two most basic properties that Alice and Bob need from a protocol are confidentiality and authenticity. Confidentiality means that Alice and Bob’s messages stay private and that Eve cannot read them. Authenticity means that Alice and Bob can be confident that they are talking to the right person and that Eve cannot spoof fake messages.

However, these aren’t the only properties that they want. Suppose that Eve hacks into Alice and Bob’s computers and steals their cryptographic keys. Even in this disaster scenario, Alice and Bob would like to ensure that Eve can’t use their keys to read any past encrypted messages that she has intercepted. This property is called forward secrecy. They would also like to prevent Eve from being able to prove that any messages that she does somehow steal are genuine. It’s bad if Eve leaks their messages to the press, but it’s less bad if they can credibly deny that they are real. This property is called deniability.

The original OTR paper was provocatively titled “Off-the-Record Communication, or, Why Not To Use PGP”. PGP is a widely-used and simple cryptographic protocol that provides good confidentiality and authenticity, but not perfect foward secrecy or deniability. OTR aims to address these shortcomings.

Since OTR began life as a challenge to PGP, we’ll begin our study of OTR by analysing PGP’s strengths and weaknesses. Then, with a working understanding of PGP under our belts, we’ll see how OTR mitigates PGP’s problems.

1.1 PGP

The PGP protocol can be used both to encrypt a message (which keeps it secret) and to sign it (which proves who wrote it). In short, when Alice wants to send a message to Bob, she first writes it in plaintext. She encrypts and signs it (more on which in a second) and sends the ciphertext and signature to Bob. When Bob receives Alice’s message he decrypts it, verifies the signature, and reads it.

If Eve intercepts Alice’s message on its way to Bob then she won’t be able to read it, and thanks to the signature she won’t be able to manipulate it without Bob noticing. This means that Alice and Bob can exchange secure messages over an insecure network.

Let’s look at how this all works.

Asymmetric encryption

At its core PGP uses an asymmetric cipher, which is an encryption algorithm that uses one key for encryption and a different one for decryption. Before a person can receive PGP messages, they must first generate a pair of mathematically linked keys called a keypair. One of these keys is their private key, which they must keep secret and safe at all costs. The other is their public key, which they can safely publish and make available to anyone who wants it, even their enemies.

Distributing public keys reliably can be surprisingly difficult, and there is a deep literature on the ways in which they can be distributed, trusted, and un-trusted. I’ve written about these mechanisms elsewhere, but here we’ll assume that Alice and Bob are able to safely retrieve and trust each other’s public keys without problem.

The critical property of asymmetric encryption is that data encrypted with a person’s public key can only be decrypted with their private key, and vice-versa.

To see why this is so useful, suppose that Alice wants to send a secret message to Bob using an asymmetric cipher. The simplest way for her to do this is to directly encrypt her message using Bob’s public key (although PGP does something different, as we’ll see shortly). To do this, Alice retrieves Bob’s public key and encrypts her message with it. She sends the resulting ciphertext to Bob, and Bob uses his private key to decrypt and read it.

Since the message can only be decrypted using Bob’s private key, which only Bob knows, Alice and Bob can be confident that Eve can’t read their message even if she intercepts it.

Why is asymmetric encryption useful?

The big feature of asymmetric encryption is that it doesn’t require Alice and Bob to agree on a shared key ahead of time. All they have to do is distribute their public keys. They don’t care if Eve discovers them (so long as she doesn’t also discover their private keys), and indeed they fully expect her to.

The opposite of asymmetric encryption is symmetric encryption. In symmetric encryption the same key is used for both encryption and decryption.

In order to exchange messages using symmetric encryption, Alice and Bob have to first agree on the symmetric key that they will use. This is tricky, since they can’t simply have one person generate a key and send it to the other. Eve might intercept the key and then use it to decrypt the messages that follow it. As we’ll see, there do exist plenty of ways for Alice and Bob to agree on a shared, symmetric key without Eve being able to discover it, but doing this does require care.

Nonetheless, neither family of algorithms is inherently more “secure” than the other, and an attacker who doesn’t know the relevant secret key will not be able to read a message that has been robustly encrypted with either type of algorithm.

How PGP uses asymmetric encryption

In fact, PGP uses both asymmetric and symmetric encryption. It does this because asymmetric encryption is slow, especially for long inputs. Using an asymmetric cipher to encrypt a long message in its entirety would be unacceptably time-consuming. By contrast, symmetric ciphers are much zippier. Alice and Bob would therefore prefer to do as much of their encryption and decryption as possible using a symmetric cipher instead of an asymmetric one. But how can they agree on a single, shared key to use with a symmetric cipher without Eve being able to see this key too?

PGP gets the best of both worlds with a neat trick. In PGP, Alice doesn’t encrypt her entire message using an asymmetric cipher. Instead, she encrypts it using a symmetric cipher, with a random symmetric key that she generates called a session key.

To allow Bob to decrypt her message, Alice needs to send him the session key. She also needs to ensure that Eve can’t read the key. To achieve this, she encrypts the session key using Bob’s public key. Now Eve can’t recover the session key without Bob’s private key, which - all being well - only Bob knows. And since Eve can’t recover the session key, she also can’t decrypt Alice’s actual message, even if she intercepts every byte of traffic that Alice and Bob exchange. Alice can therefore confidently send both the symmetrically-encrypted message and asymmetrically-encrypted session key to Bob.

To read Alice’s message Bob reverses Alice’s process. He uses his private key to decrypt the symmetric session key, and then uses the session key to decrypt the actual message. With PGP Alice and Bob get the convenience of asymmetric cryptography with the speed of symmetric.

Cryptographic signatures

However, even though Bob is the only person who can read Alice’s message, at the moment he has no proof that the message really was written by Alice. As far as he’s concerned it could have been written and encrypted by Eve pretending to be Alice, or Eve could have intercepted and manipulated a real message from Alice. To prove to Bob that she wrote her message, Alice uses PGP to cryptographically sign it before sending it.

A cryptographic signature is a blob of data attached to a message that allows the recipient to prove to themselves who wrote the message. It also allows them to satisfy themselves that the message has not been tampered with. Signatures can be generated in several different ways, including the same kind of asymmetric cryptography that Alice and Bob just used to encrypt their messages.

When encrypting and decrypting a message using asymmetric cryptography, Alice and Bob exploit the fact that a message encrypted using a public key can only be decrypted using the corresponding private key. To sign a message, they exploit the equivalent but inverse fact that a message encrypted with a private key can only be decrypted using the corresponding public key.

To produce a naive signature, Alice can take her encrypted message and encrypt it again using her private key. The result of this operation is the message’s signature. She can attach this signature to her encrypted message and send both it and the message to Bob.

This signature is useful because Bob can decrypt it using Alice’s public key, and verify that the result is equal to Alice’s encrypted message. This proves to Bob that the signature was produced using Alice’s private key, and therefore that the message was signed and written by Alice. He also knows that the message hasn’t been tampered with in transit, because if it had then the result of decrypting the signature would no longer equal the encrypted message. In order to mess with the message without being detected, Eve would need to update the signature too. However, since she doesn’t know Alice’s private key, she can’t generate a valid signature for her mutated message.

This is the principle underlying all types of cryptographic signature.

Cryptographic signatures in practice

In practice, Alice doesn’t actually sign her encrypted message directly. This is because, as we know, asymmetric encryption is slow. On top of this, signing the entire message would produce a signature of the same length as the message, which would require unnecessary bandwidth to send. What’s more, short messages would produce short signatures, which could be easy for an attacker to forge, even without knowing Alice’s secret key.

Alice therefore starts by passing her message through a hash function, which is an algorithm that produces a random-seeming but consistent and fixed-length output for a given input. She then signs the output of the hash function with her private key.

Putting this all together gives us the following picture:

When Bob receives Alice’s message and signature, he uses a hash function to verify the signature too. He decrypts Alice’s signature using her public key, but then instead of comparing the result to her message directly, he first hashes her message and compares the output to the decrypted signature. If they match then Bob can be confident that the message is authentic.

The problems with PGP

Encryption and signatures are how PGP gives Alice and Bob confidentiality and authenticity. We’ve seen how Eve can’t decrypt Alice’s messages because she doesn’t know Bob’s private key, and so she can’t decrypt the symmetric session key. She can’t spoof a fake message from Alice to Bob because she doesn’t know Alice’s private key, and so won’t be able to generate a valid signature. If everything goes perfectly, PGP works perfectly.

However, in the real world, we also have to plan for the times when everything does not go perfectly. This is where PGP falls down, and where OTR aims to improve on it. PGP relies heavily on private keys staying private. If a user’s private key is stolen (for example, if their computer is hacked and all their files stolen) then the security properties previously underpinned by it are blown apart. Suppose that Eve steals a copy of Bob’s private key and intercepts Alice’s message on its way to Bob. She’ll be able to decrypt the session keys that Alice encrypts using Bob’s public key, and then use them to decrypt Alice’s messages. If she steals a copy of Alice’s private key then she can use it to sign fake messages that Eve herself has written, making it look like these messages came from Alice.

All encryption is to some degree underpinned by the assumption that secret keys stay secret, and so we should expect any protocol to be severely damaged if this assumption is broken. But with PGP the fallout is worse than just leaking confidential messages. We know already that if Eve steals a private key then she can use it to decrypt any future PGP messages that she intercepts and that were encrypted using the corresponding public key. But suppose that Eve has been listening to Alice and Bob for months or years, patiently storing all of their encrypted traffic. Previously she had no way to read any of this traffic, but with access to Bob’s private key she can now decrypt all of their historical session keys and use them to decrypt all of their old, previously-secret messages.

But it gets even worse. Alice cryptographically signed all her PGP messages so that Bob could be confident that they were authentic. However, whilst generating a signature requires Alice’s private key, verifying it only requires her public key, which is typically freely available. This means that Eve can use Alice’s signatures to verify the authenticity of messages that she steals from Bob just as well as Bob can. If Eve gets access to Alice and Bob’s signed messages, she also gets access to a cryptographically verifiable transcript of their communications. This prevents Alice and Bob from credibly denying that the stolen messages are real. In a few sections’ time we’ll look at some real-world examples of how cryptographic signatures like this can cause serious problems for the victims of hacks.

PGP does give confidentiality and authenticity. But it’s brittle, and it isn’t robust to private key compromise. We’d ideally like an encryption protocol that better mitigates the consequences of a hack. In particular we’d like two extra properties. First, we’d like deniability, which is the ability for a user to credibly deny that they ever sent hacked messages. And second, we’d like forward secrecy, which is the property that if an attacker compromises a user’s private key then they are still unable to read past traffic that was encrypted using that keypair.

In part 2 of this series we’ll examine these two properties in detail and see why they are so desirable. Then in parts 3 and 4 we’ll look at how Off-The-Record-Messaging works and how it provides them.