Systems design for advanced beginners

06 Apr 2020

This post is part of my Programming for Advanced Beginners series. Subscribe now to receive specific, actionable ways to make your code cleaner, every other week, entirely free.

You’ve started yet another company with your good friend, Steve Steveington. It’s an online marketplace where people can buy and sell things and where no one asks too many questions. It’s basically a rip-off of Craigslist, but with Steve’s name instead of Craig’s.

You’re going to be responsible for building the entire Steveslist technical platform, including all of its websites, mobile apps, databases, and other infrastructure. You’re excited, but also very nervous. You figure that you can probably cobble together a small website, since you’ve done that a few times before as part of your previous entertaining-if-morally-questionable escapades with the Stevester. But you have no idea how to even start building out all of the other infrastructure and tools that you assume lie behind large, successful online platforms.

You are in desperate need of a detailed yet concise overview of how real companies do this. How do they store their data? How do their different applications talk to each other? How do they scale their systems to work for millions of users? How do they keep them secure? How do they make sure nothing goes wrong? What are APIs, webhooks and client libraries, when you really get down to it?

You send a quick WhatsApp to your other good friend, Kate Kateberry, to see if she can help. You’ve worked together very effectively in the past, and she has decades of experience creating these types of systems at Silicon Valley’s biggest and most controversial companies.

She instantly accepts your job offer. You had actually only been ringing for some rough guidance and a good gossip, but you nonetheless instantly accept her acceptance. No point looking a gift horse in the mouth, even when you don’t have any money to pay her. Kate proposes that her first day be 5 weeks ago in order to help her smooth over some accounting irregularities. She can come into the office sometime next week. You feel encouraged and threatened by her eagerness.

Kate bounces into your offices in the 19th Century Literature section of the San Francisco Public Library. “OK let’s do this!” she shouts quietly. “What have we got so far? How are all our systems set up? What’s the plan?” You lean back in your chair and close your laptop, which was not turned on because you have left your charger at home. You steeple your fingers in a manner that you hope can be described as “thoughtful”.

“Let me flip that question around, Kate. What do you think the plan should be?”

Kate takes a deep breath and paints an extremely detailed vision of the Steveslist platform five years into the future and the infrastructure that will power it.

Before we start (says Kate), I want to make it clear that I’m not saying that any of this is necessarily the “right” way to set up our infrastructure. If someone you trust more than me says something different then you should probably do what they say. There are many tools out there, each with different strengths and weaknesses, and many ways to build a technology company. The real, honest reasons that we will make many of our technological choices will be “we chose X because Sara knows a lot about X” and “we chose Y on the spur of the moment when it didn’t seem like a big decision and we never found the time to re-evaluate.”

Nonetheless, let’s fast-forward five years into the future. Now Steveslist has two main consumer-facing products:

- The Steveslist web app

- The Steveslist smartphone apps

These are the main ways in which users directly interact with the Steveslist platform. In addition, we also provide an API that allows programmers to build power-tools on top of the Steveslist platform that, for example, create listings for hundreds of items programmatically. To support this, we offer:

- A Steveslist API

- Steveslist API client libraries that make it easy for programmers to write code that talks to our API

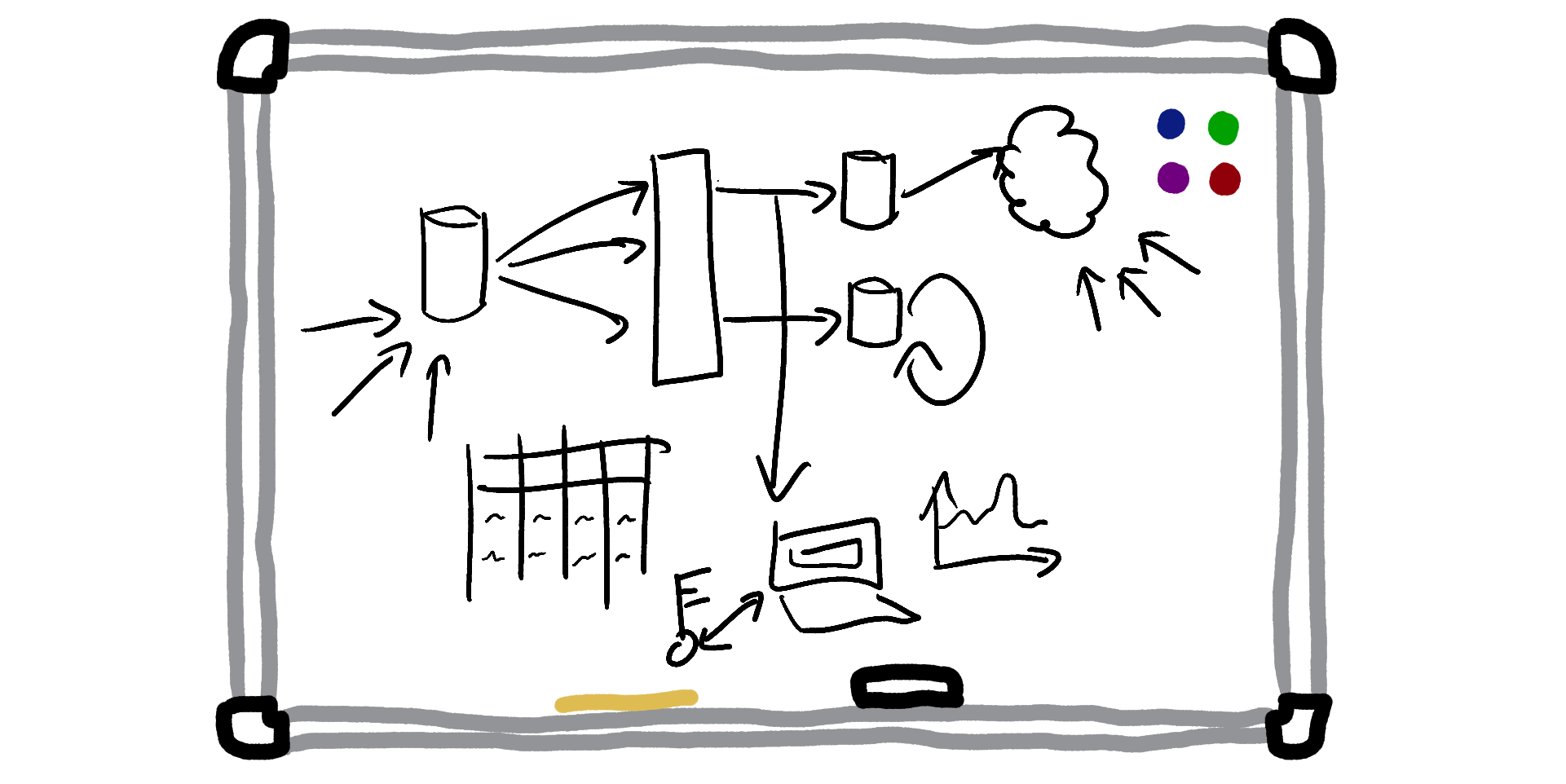

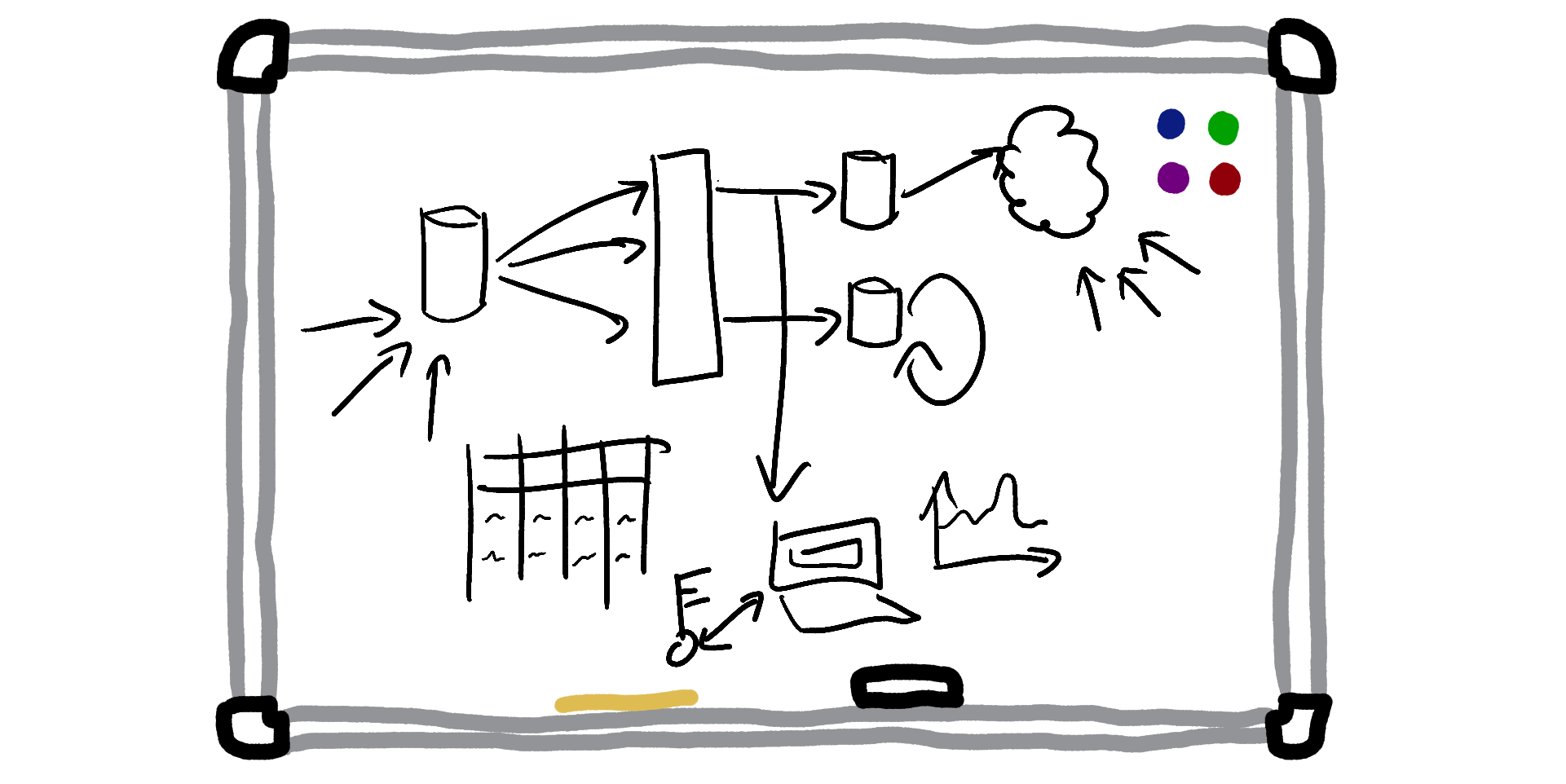

Here, I’ll draw a diagram on the whiteboard:

+-----------+ +--------------+ +-----------------+

|Web Browser| |Smartphone App| |Client Libraries/|

+-----+-----+ +------+-------+ |Other API code |

| | +-------+---------+

| v |

| +-----+------+ |

+--------->+ Steveslist +<-----------+

| Servers |

+------------+

Finally, we have many, many services running in the background that provide the data and power to these external-facing applications:

- Webhooks - to notify users when something happens to their account, such as “order placed”

- User password authentication - to securely log users in

- SQL database - the main Steveslist data store. Needs to be highly scalable and reliable

- Free-text searching system - to power the search box where people can look for broad search terms like “TVs” or “motorbikes”

- Internal tools - to help us administer the Steveslist platform, and to take actions like issuing sternly-worded warnings to malicious users

- Cron jobs - to run regular tasks that do anything from generating invoices, to billing customers, to sending as much of our users’ data as possible to third-party ad networks

- “Pubsub” system - to allow us to take asynchronous actions on different trigger events (such as “when a new user signs up, send them a welcome email”)

- Big data analytics system - to allow us to run enormous queries over the entirety of Steveslist’s data

- And many more that we’ll talk about another day

Let’s go through each of these systems in turn. Let me know if anything isn’t clear, if you have any questions, or if you think I’ve got something wrong.

Before we start - what is a server really?

Before we start, let’s define some important terms. In fact, let’s just define one. We’re going to talk a lot about “servers” today. But what is a server, when you really get down to it?

For our purposes, a server is a computer that runs on a network and listens for communications from other computers. When it receives some data from another computer it performs some sort of action in response and - usually - sends back some data of its own. For example, a web server listens on a network for HTTP requests and sends back webpages and information in response. A database server listens for database queries and reads and writes data to the database that it is running.

This brief description skips out entire degrees and careers of detail, and there are of course far more precise and accurate ways to define the word “server”. But this should get us through until dinnertime. What did you say? What’s a “network” really? A good question for another day.

Now we’re ready to talk about the Steveslist platform.

Steveslist web app

This is the main Steveslist product. It’s just a normal web app, very similar to any website that you’ve built before, except much bigger. It’s a modern “single-page app” (SPA). The “single” in “single-page app” refers to the fact that the user’s browser almost never has to fully reload the page as the user clicks around our site. Instead, when the browser makes its first HTTP request to our servers, we send it back a basic, skeleton HTML page and a big pile of JavaScript code. This JavaScript code executes inside the browser, and updates the view of the page in response to the user’s actions. When the JavaScript wants to send or retrieve data from Steveslist, it sends an Asynchronous JavaScript XML Request (almost always called AJAX for short) in the background to a URL. When our server responds, the JavaScript uses the response to update the browser view accordingly.

+----------+1.User's browser visits steveslist.com. +----------+

| | It sends an HTTP request to the | |

| | Steveslist servers | |

| +--------------------------------------->| |

|User's Web| |Steveslist|

| Browser |2.Steveslist server responds with a | Servers |

| | skeleton HTML page that instructs the | |

| | browser to request additional | |

| | JavaScript files. | |

| |<---------------------------------------+ |

| | | |

| |3.User's browser requests and receives | |

| | these JavaScript files from the | |

| | Steveslist server. | |

| +--------------------------------------->| |

| |<---------------------------------------+ |

| | | |

| |4.User's browser executes the JavaScript| |

| | code. The code sends more requests for| |

| | the user's data to the Stevelist | |

| | server, and updates the browser UI to | |

| | display it. | |

| +--------------------------------------->| |

| |<---------------------------------------+ |

+----------+ +----------+

robertheaton.com is not a single-page app. Whenever you click on a link, the browser has to reload the entire page. twitter.com is a single-page app. Whenever you click on a link, the browser dynamically updates a small portion of tthe page without forcing a full refresh.

SPAs are a lot of work to build and maintain, but they sure look good.

Steveslist smartphone apps

We provide Steveslist smartphone apps for both iOS and Android. They are conceptually very similar to our single-page web app. Both our smartphone and web apps make HTTP requests to our servers. Then our servers receive these requests, do some work and return an HTTP response. Finally, both our smartphone and web apps update their display in order to communicate with the user.

Since our smartphone apps are performing the same operations as the web app (for example, create listing, send message, etc), they can usually even send their requests to the exact same URLs as the web app. The only extra work that we have to do is to develop the frontends of the apps themselves. Some frameworks even make it possible to write mobile apps using JavaScript, allowing you to reuse code and logic across platforms.

Steveslist API

We allow users and third-parties to write code that programmatically interacts with our platform. In the same way that people can use the Twitter API to write code that reads; likes; and creates Tweets, we allow them to use the Steveslist API to search; buy; and list items.

Programmers use our API by writing code that makes HTTP requests to our API endpoints. For example, in order to retrieve a list of all their listings, the programmer sends an HTTP GET request to api.steveslist.com/v1/listings. We respond with the data they requested, formatted as JSON. JSON stands for JavaScript Object Notation, but JSON is not specific to JavaScript and can easily be interpreted by any programming language. A JSON response to a request to retrieve all of a user’s listings might look something like this:

{

"listings": [

{

"id": 2178123867,

"name": "Stolen TV",

"country": "US",

"city": "San Francisco",

"price_amount": 1000,

"price_currency": "usd",

# etc...

},

{

"id": 182312679,

"name": "Stolen Bicycle",

"country": "US",

"city": "San Francisco",

"price_amount": 2000,

"price_currency": "usd",

# etc...

}

]

}

This structured response format is very easy for a program to parse, which means that the code that made the request can trivially interpret and use the data from our API.

Users identify or authenticate themselves to our API using an API key. This is, roughly speaking, the API equivalent of a password. It is a long, random string that we generate and display on a user’s “Settings” page. Users include their API key as an HTTP header with every HTTP request that they (or their code) makes to the API. When we receive an API request we check to see whether the attached API key corresponds to a Steveslist user. If it does then we perform the request on behalf of that user.

If a programmer wants to, they can manually build HTTP requests to our API themselves, using their language’s standard HTTP library. For example, in Python they might write:

import requests

url = 'https://api.steveslist.com/v1/listings/'

listing_params = {

"name": "Stolen TV",

"country": "US",

"city": "San Francisco",

"price_amount": 1000,

"price_currency": "usd",

}

api_key = "YOUR_API_KEY_GOES_HERE"

response = requests.post(

url,

data=listing_params,

headers={"X-Steveslist-API-Key": api_key},

)

However, we make life easier for programmers by providing client libraries.

Steveslist client libraries

A client library is a library that “wraps” the functionality of the Steveslist API. This means that anyone using the client library doesn’t need to know anything about the fine details of the Steveslist API. Instead, they can just write:

import steveslist

listing = steveslist.Listing.create(

name="Stolen TV",

country="US",

city="San Francisco",

price_amount=1000,

price_currency="usd",

api_key="YOUR_API_KEY_GOES_HERE"

)

Our libraries turn the parameters that they are given into appropriately formatted HTTP requests, which they send to the Steveslist API as normal. We’ve written client libraries for every major programming language that we could think of, and they are by far the most common way that people interact with our API.

Webhooks

We’ve seen how Steveslist users can use our API to programmatically interact with their account. In addition, many users also want us to proactively tell them whenever something happens to their Steveslist profile. For example, suppose that someone wanted to fully automate the process of selling items on Steveslist. Whenever a customer pays for an item using our new, mostly-secure StevePay system, they want to send the customer a thank you email and automatically instruct their warehouse to ship a stolen TV to the order address. Our seller could constantly and repeatedly query the Steveslist API asking “Any new sales? Any new sales?” However, this would be very inefficient, and would put a lot of unnecessary load on our servers.

Instead, we provide an industry standard system called webhooks. A webhook is an HTTP request that we send to our users whenever something interesting happens to their account. It contains all the data describing the event that just happened - for example, the item ID, the price, the buyer ID, buyer address, and so on. Webhooks allow users to automatically perform response actions, such as the aforementioned email and auto-shipping.

To use webhooks, the user tells us the URL to which they would like us to send their webhooks (for example, steveslistwebhooks.robertheaton.com. They set up a web server at that URL that will receive and action these webhook notifications.

1.Buyer purchases an 3.The seller's server receives the webhook,

item as normal. and uses the information in it to

automatically process the order.

+---------------+ +-----------------+

|Buyer's Browser| |Seller's Webhook-+

+------+--------+ |Receiving Server |

| +------+----------+

| ^

| |

| |

| +-----------+ |

+--->+ Steveslist+----------+

| Server |

+-----------+

2.Once the transaction has been completed,

Steveslist looks up the seller's

webhook URL (if set). We then send

an HTTP request to this URL,

containing the details of the purchase.

The user deploys code on their web server that performs the appropriate response actions whenever it receives a webhook from us. We don’t only send webhooks when an item is purchased - we also send them when a user receives a message; when one of their items is removed by an admin; or when a buyer makes a complaint. This enables Steveslist sellers to automate not just the listing of items, but also the selling and shipping of them too.

Webhook complications

Webhooks come with two main complications - security and reliability. First, let’s talk security. The endpoint to which the seller instructs us to send their webhooks is accessible to anyone on the internet. Anyone who knows the URL can send it fake webhooks, and if our seller isn’t careful this could allow an attacker to trick them into, for example, sending the attacker free stuff. A seller’s webhook URL should be difficult to find, since the seller won’t publicize its existence, but obscurity is not the same as security.

To allow our sellers to verify that a webhook really was sent by Steveslist, we cryptographically sign our webhook contents.

Cryptographic signing

Cryptographic signing is a deep and subtle topic. Here’s a condensed version of how we use it to secure our webhooks.

When a seller enables webhooks for their account, we generate a random “shared secret key”. We tell the seller to copy this key over to their webhook-receiving server and keep it secure, so that its value is known only by us and the seller. Whenever we send a webhook, we take this shared secret, combine it with the contents of the webhook by using a cryptographic hash function called HMAC, and get back a long, random-seeming, but entirely deterministic “signature” for the webhook.

Webhook contents +----------+

(eg. {"id": 123...}) |

v

+---+----------+

|HMAC Algorithm|----->Webhook signature

+---+----------+

^

Shared secret key |

(eg. 123mhu23jy8xdwgmd...)+---+

We include this signature in our webhook body, for example:

{

"action": "item_sold",

"price": 100,

// ...more params...

"signature": "234gj98d49j834978gf39t78ndn98g7dq3ng897308y7"

}

When the seller’s webhook-receiving server receives a webhook, it takes the shared secret and webhook contents and calculates what it expects the signature to be in exactly the same way that we did. It compares the result to the signature attached to the webhook; if they match then it accepts and processes the webhook. Since the signature can only be generated using the shared secret known only by us and the seller, the webhook-receiving server can be confident that the webhook was sent by us. If the signatures don’t match, however, the server rejects the webhook.

Note that all of the signature verification code must be written and maintained by the sellers. We can provide them with encouragement and examples, but we can’t force them to verify signatures correctly, or even at all. For some real-world examples, look at how Stripe and GitHub sign their webhooks.

Reliability

We also need to consider what happens when our webhooks go wrong and what guarantees we want to make to our users about them. If we try to send a webhook but can’t connect to the user’s server, what should we do? What if we successfully connect to their server and send the webhook, but their server sends back an error? What if we send the webhook but the server hangs for twenty seconds before disconnecting without telling us what happened?

There are tradeoffs involved here that require clear communication and a surprising amount of infrastructure to manage. We at Steveslist choose to guarantee that we will deliver webhooks “at least once”. This means that if a webhook fails to send then we will keep trying (a large but not infinite number of times) until it does. If we’re not sure whether a webhook succeeded or failed, we will keep trying until we are sure that an attempt has succeeded. This might occasionally result in us sending the same webhook twice, but it’s the seller’s responsibility to have their code handle this gracefully instead of sending the same customer five stolen TVs instead of the one that they ordered.

“What do you think so far?” asks Kate. “Is this roughly what you’ve been thinking?” You make a non-committal face and take a big bite of a nearby sandwich in order to preclude any further discussion. Kate continues:

Let’s talk about the backend systems that will power some of our most important features.

User authentication via a password

Most users sign into the Steveslist website and smartphone apps using a username and password. There are other ways of signing into the website, like OAuth - we’ll cover them another time.

We will have to store our users’ passwords very securely. Not only is a user’s password the thing they use to sign in (or authenticate) to Stevelist, but for many users they’re probably the same password that they use to sign in to many other services too, despite all the warnings that this is a bad idea. They only have so many children with so many birthdays, after all.

Rupert Herpton has written the seminal tutorial on how to secure passwords, which I’m sure you’ve read already. Just in case you need a refresher, the crux of the matter is that we mustn’t ever store passwords in their original, plaintext form, anywhere. We mustn’t store them in plaintext in a database, in a log file, or in any other part of our system. Instead, before storing a password, we must first hash it using a hash function such as bcrypt.

A hash function is a “one-way” function that takes an input and deterministically converts it into a new, seemingly-random string. Calculating a hash value from an input is computationally very easy, but reversing the transformation and recovering the original input from its hash value takes so much time and computing power that it is, practically-speaking, impossible.

+---------+ Easy +----------+

| |------------>| |

|Plaintext| |Hash value|

| |<------------| |

+---------+ Essentially +----------+

Impossible

Since we only store the hash values of our users’ passwords, if a hacker somehow stole our password database (heaven forbid) (touch wood) then they would only be able to see the passwords’ hash values. They wouldn’t be able to easily turn these hash values back into plaintext passwords, meaning that they wouldn’t be able to use them to login to Steveslist, and they won’t be able to take advantage of all the people who re-use passwords across different services.

Since we only store password hash values, when we want to check whether a login password that a user has given us is correct we first calculate its hash value, and compare the result to the hash value in our password database.

+--------------+

|User's Browser|

+-----------+--+

1.User attempts to | ^

log in: | | 3. Server logs the user in

| | if password matches, and

username: steve | | returns an error if it does not.

password: 12345 v |

+--+--------+--+

| Steveslist |

| Server |

+--------------+

|

2.Server computes | |username|password_hash|

the hash of the | +----------------------+

password and compares +---->+steve |23jy7213y7jO |

it to the value in the |kate |21897213hh21 |

database. |... |... |

As previously mentioned, we also have to be careful not to log passwords in any of our debug output. This can be an easy mistake to make - if you log all of the parameters of every HTTP request, just in case you need it, you will certainly be logging user passwords. Facebook logged passwords in plaintext for many years, and whilst it didn’t seem to affect their stock price I’m sure it made them feel pretty silly for a day or two.

Kate pauses for breath. You pretend to take notes on your out-of-battery laptop.

Let’s talk about infrastructure.

Database servers

Steveslist’s primary data store runs a common flavor of SQL database called MySQL. I won’t talk much about SQL here - the specifics of how it works aren’t too important, and you can find them on Google if you’re interested. Since we are so successful, we have a huge and growing amount of data to manage. We’ve started to become acutely aware that databases aren’t magic. They run on computers, just like any other program. As the volume of data in a database grows, the computer’s hard drive and memory starts to fill up. At the start of the company the easiest way to deal with this problem was to run our database on a single computer (or machine) with an enormous hard drive. But this could only stave off the problem for so long. Eventually our database contained more data than could be stored on any reasonable hard drive, and the database started to get slower and slower as we forced it to search through more and more records.

We had to take an entirely new approach, and reconfigure our database to store its data on multiple computers. We did this using sharding.

Sharding

Sharding a database means splitting its data into chunks (or “shards”) and storing each chunk on a separate machine. All of the machines that make up a database are together known as a database cluster. How you split data between machine in your cluster depends on your application and the types of operations you will be performing. For Steveslist we chose to split out our data by user. This means that all of the data for a given user is stored on the same machine. This includes their profile information, their listings, their messages, and so on. Data that doesn’t have a corresponding user (like “Deals of the Day”) can be sharded using a shard key other than user, or not sharded at all if the dataset is sufficiently small.

This means that we need an extra “routing” layer in front of our database, which knows which database machine is able to service which queries. We could either make our application servers (the servers that execute our code) responsible for knowing the mapping of user IDs to database shards, or have a centralized “router” that all servers send their requests to, and which is responsible for working out the appropriate machine to forward the request on to. Both approaches have their advantages. Making application servers responsible for maintaining the mapping reduces the number of hops that a request has to make, speeding them up. But having a centralized router makes updating the shard mapping much easier, since you only have to update it in one place.

If application servers are responsible for knowing the shard layout, we have a system that looks like this:

+ + +

| | |

| Requests from users |

| | |

v v v

+------+----------+--------------------+

| Application |

| Server |

| |

|Database sharding config: |

|* DB Server 1: IDs between 1-10000 |

|* DB Server 2: IDs between 10000-20000|

|* DB Server 3: IDs between 20000-30000|

+-+----------------+-----------------+-+

| | |

|ID:501 |ID:15362 |ID:22361

| | |

v v v

+-----------+ +-----------+ +-----------+

|DB Server 1| |DB Server 2| |DB Server 3|

+-----------+ +-----------+ +-----------+

If we have a centralized database router, we have a system that looks like this:

+ + +

| | |

| Requests from users |

| | |

v v v

+------+----------+--------------------+

| Application |

| Server |

| |

|Database sharding config: |

|* ??? Application Server has no idea |

+------------+-----------+-------------+

| |

Application server sends all database

queries to the database router, which

forwards them to the correct shard.

| |

v v

+--------------+-----------+-------------+

| Database router |

| |

|Database sharding config: |

|* DB Server 1: IDs between 1-10000 |

|* DB Server 2: IDs between 10000-20000 |

|* DB Server 3: IDs between 20000-30000 |

+---+----------------+---------------+---+

| | |

|ID:501 |ID:15362 |ID:22361

| | |

v v v

+-----------+ +-----------+ +-----------+

|DB Server 1| |DB Server 2| |DB Server 3|

+-----------+ +-----------+ +-----------+

How do we decide which database to assign each user to? However we want. We could start by saying that users with odd-numbered IDs are assigned to shard machine 1, and those with even-numbered ones are assigned to shard machine 2. We could hope that this random assignment results in balancing our data relatively evenly between our shards.

However, it’s possible that we might have a small number of power users who create much, much more data than others. Maybe they create so much data that we want to allocate them a shard of their own. This is completely fine - we have complete control over how users are assigned to shards. Random assignments are usually easiest, but are by no means the only option. We can choose to assign users to shards randomly - except for user 367823, who is assigned to shard 15, which no other user is assigned to.

If a shard gets too big and starts to fill up its machine’s hard-drive, we can split it up into multiple, smaller shards. How do we migrate the data to these new shards without having to turn off our platform for a while? Probably using a sequential process like:

- “Double-write” new data to both the old and new shards. Continue reading data from the old shard

- Copy over all existing data from the old shard to the new shard. Continue double-writing to old and new shards

- Convince ourselves that the old and new shards contain the same data. We could do this by comparing snapshots of the databases, and/or by reading every query from both databases, comparing them, and alerting if the data is different

- Once we’re confident that the new and old shards contain the same data, we switch to reading from the new shards. We continue double-writing in case we need to switch back

- Once we’re confident that this step has been successful, stop double-writing and delete the old shard

Rupert Herpton has written a great article about a broadly-similar type of migration that goes into much more detail. In short, the process of migrating data between database shards is detailed and finicky, but also entirely doable and logical. Some types of database can even automatically take care of sharding for you.

Replication

We will take great care to make sure that our data doesn’t get accidentally deleted and our database servers don’t randomly stop working. But accidents happen, and sometimes computers do randomly stop working. To mitigate the fallout of a database-related disaster, we replicate our data across multiple machines in (close to) realtime.

Client writes new

data to DB Server A

|

v

+-----+-----+

|DB Server A|

++---------++

| | DB Server A quickly replicates

v v the new data to DB Servers B and C

+----------++ +-+---------+

|DB Server B| |DB Server C|

+-----------+ +-----------+

Realtime replication has two main benefits. First, it means that if one of our database servers explodes, catches fire, or otherwise stops working, we have multiple almost-perfect copies of it that can seamlessly pick up the slack. In a straightforward, vanilla failure, users of our services may never know that anything has gone wrong. The second benefit of replication is that we can distribute queries for the same data across multiple database servers. If lots of users are asking to read data from the same database, we can split their queries up across all of our copies, meaning that we can handle more queries in parallel.

Clients can query the same data

from any of DB Servers A,B,or C

| | | | | | |

| | v v v | |

| | +-+---+---+-+ | |

| | |DB Server A| | |

| | +-----------+ | |

| | | |

v v v v

+---+-------+ +-----+-+---+

|DB Server B| |DB Server C|

+-----------+ +-----------+

Note that database replication is not the same concept as making database backups. Replication happens in (close to) realtime, and is designed to deal on-the-fly with isolated problems in your live (or production) systems. Database backups are performed on a schedule (for example, once a day), and the copies of the data are stored separately, away from production systems. Backups are designed as a final safeguard against widespread, catastrophic data loss, as might happen if all your data centers burned down.

Pretend that you work in the call centre of a big bank, where people are constantly calling you up in order to send money transfers and ask about their current balance. Replication is the equivalent of hurriedly writing down transfer details into multiple books, as you receive them, just in case you lose one of the books. Making backups is the equivalent of photocopying those books once a day and storing the copies in your filing cabinet.

Replication

The process of replication is conceptually quite straightforward. Whenever new data is written to our database, we copy it to multiple machines. This means that if/when a machine fails we can continue querying its siblings, with no user-facing impact. It also means that we can spread our queries out across multiple copies of the same data, resulting in faster query response times.

However, the details of how we do this are important, subtle, and situation-dependent. There’s no right way to do replication - as is so often the case, the exact approach that you take depends on the specific requirements and constraints of your system.

Replication is complicated by two inconvenient facts about the real world. First, database operations randomly fail sometimes. When we attempt to replicate our data from one server to another, things will occasionally go wrong, causing our machines to become out of sync, at least for a period. Second, even in periods of smooth operation, replication is not instantaneous. When new data is written to our database cluster, some servers in the cluster will always know about the update sooner than others. When choosing a replication strategy we must be aware of these limitations and how they impact our particular application. For example, maybe it’s OK to risk the number of “likes” on a post being slightly out of sync and out of date, but not the amount of money in a user’s bank account.

One of the biggest decisions we must make when choosing a replication strategy is whether we want our replication to be synchronous or asynchronous.

Asynchronous vs synchronous replication

Replication can be handled either synchronously or asynchronously. These words come up in a lot of different places in systems design, but they always fundamentally mean the same thing. If an action is performed “synchronously” then this means that it is performed while something waits for it. If you wanted to send a letter synchronously then you would got to the Post Office, give your letter to a postal worker, sit and wait in the corner of the Post Office for a few days, and only go home when the postal worker confirmed that your letter had arrived safely.

By contrast, if an action is performed “asynchronously” then this means that the initiator of the action doesn’t wait around for it to be finished. Instead, they just continue with the rest of their work while the action is worked on in the background. The real Postal Service is asynchronous; you give your letter to a postal worker, then leave and continue with your life while the Postal Service delivers your letter. Asynchronous actions can send back notifications of the outcome of the action if they want (“Your letter has arrived and was signed for” or “Mr. Heaton, your dry-cleaning is ready”), but they don’t have to.

How do these principles apply to database replication? In synchronous replication a client writes its new data to a database server and then waits. This server doesn’t tell the client whether their write has been completed successfully until it has finished fully replicating the client’s data across all of its sibling servers. Then, and only then, does the client continue executing the rest of its code.

In asynchronous replication the client writes its data to the first database server, as before. But this time the first server tells the client that the write was successful as soon as it has written the data to its own data store. It kicks off the replication process in the background, and doesn’t wait for it to complete, or even start, before it tells the client that the write was successful. This means that the asynchronous operation appears much faster than the synchronous one, because the client doesn’t have to wait for all the replication to complete before it can continue on with the rest of its work. However, if the background replication fails then the client will believe that it has successfully written its data to the database when it actually has not. This could cause problems, the imagination of which is left as an exercise for the reader.

The synchronous approach is slower but “safer” than an asynchronous approach. The database never claims to have successfully received and stored any data until it has finished every single step of doing so. Because the client waits for full confirmation before proceeding, it is guaranteed to never encounter a situation where the client believes that it has written some data to the database, but the database has secretly partially dropped the data on the floor.

Which approach is better? It depends. Do you care more about speed or correctness? Is it OK to occasionally have inconsistent data if it significantly speeds up the system’s operation? Or will even a single mistake cause airplanes to start falling out of the sky?

Database replication systems face other interesting problems too. Many of these problems are “logical” rather than “technical”, and don’t require a detailed understanding of the complex software and networking protocols underlying the system. To help picture some of them, imagine that you’re back in the call centre from a few paragraphs ago. You work with many other colleagues. Together you play the role of database servers. People call you up to transfer money and ask about their current balance. You and your colleagues write information about new transfers down on paper, and replicate it between yourselves by calling each other up.

The problems faced by our database cluster are identical to those faced by our call-centre. What happens if two people call in and try to update the same piece of data at the same time by talking to two different employees? Maybe we solve that by having a “leader” employee who is the only one authorized to serve calls from people trying to create transfers. All the other employees are only allowed to answer queries about current balances. OK, so what happens if the leader has a stroke and dies after they’ve received some new data, but before they’ve told everyone else about it? What if a “follower” employee has a temporary seizure for a few seconds and misses some data updates from the leader? What if we’re never entirely sure which of our employees are dead or alive?

This is not an approximate metaphor that breaks down if you look too hard or start asking awkward questions. Understand this weird call-centre and you understand database replication. Read this blog post and you really understand replication.

Backups

In addition to realtime replication, we also store regular backups of our entire database in order to protect against catastrophic disaster. We copy all of the data in our database, store it somewhere safe, and mark it as something like “database backup, 2020-05-11:01:00”.

+----------+

| Database +----------------> database backup, 2020-05-11:01:00

+----------+ database backup, 2020-05-10:01:00

database backup, 2020-05-09:01:00

If our entire database - or some fraction of it - somehow gets wiped out, we grab the most recent backup available and load it into new database machines.

+----------+

| New |

| Database +<---------------- database backup, 2020-05-11:01:00

+----------+ database backup, 2020-05-10:01:00

database backup, 2020-05-09:01:00

Such a calamity could be caused by a cyberattack, a disaster in our data centre, a database migration gone horribly wrong, or any number of unlikely but potentially company-destroying reasons. Unlike realtime replication, restoring a database from a backup is a slow process that our users will definitely notice. Our entire system will likely be offline until the restoration is complete. We will have lost all database updates that occurred after the last backup but before the disaster. And there will no doubt be a large number of knock-on effects as users and systems try to access data that used to be there but is now lost forever. Nonetheless, these are all much less terrible than the complete, irrevocable loss of all our company’s data and with it, our company.

That’s a whole lot of detail about our primary SQL database. Let’s talk about some other ways in which we store and query data.

Free-text searching

A standard SQL database is very good at answering well-defined and specific queries. For example:

- Give me all the item listings created by user #145122 in the last 90 days

- Give me the listing details for item #237326921

- Give me the count of new listings per day created in San Francisco with the label “Electronics”

You can retrieve this kind of data using SQL queries that look something like this:

SELECT *

FROM items

WHERE

user_id = 145122 AND

created > currentDate() - 90

or

SELECT

DATE_TRUNC('day', i.created) AS day,

COUNT(*)

FROM items AS i

INNER JOIN labels as l

ON i.id = l.item_id

WHERE

i.city = 'San Francisco' AND

l.text = 'electronics'

GROUP BY 1

ORDER BY 1 DESC

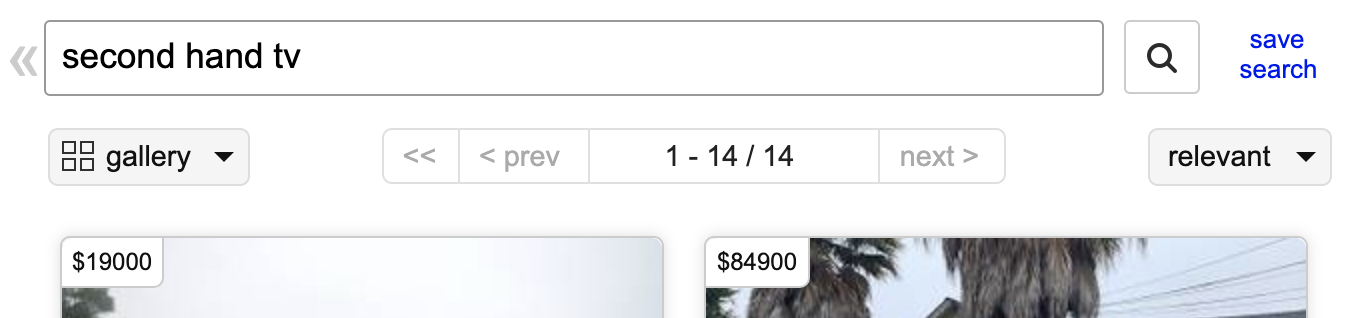

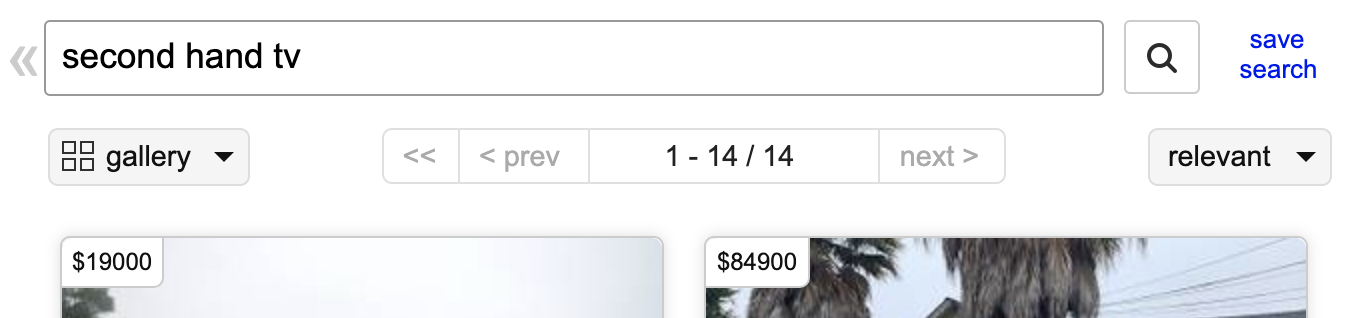

You’ll notice that these queries contain a lot of very “precise” operators, like equals- and greater-than-signs. But how would you write a SQL query that could return a list of items that match a Google-style “full-text” search, like “second-hand TV”?

This would be difficult. You could try the SQL LIKE operator, which allows you to find records containing a pattern, such as a sub-string. For example, the following query finds all items with a description containing the sub-string second-hand TV:

SELECT *

FROM items

WHERE description LIKE '%second-hand TV%'

However, this query will only match the very specific sub-string that it was given. It won’t match “TV that is second-hand” or “2nd-hand TV”, or “sceond-hnad TV”. Given enough perseverance you could theoretically construct a giant SQL-query that covered as many of these permutations as you had patience for:

SELECT *

FROM items

WHERE

description LIKE '%second%hand%TV' OR

description LIKE '%second%TV%hand' OR

-- …and so on and so on for another bajillion ORs…

However, the resulting query would be slow and cumbersome, and would still miss many important edge-cases that you hadn’t thought of. And even if you did get back a useful list of search results, you’d still have a lot of work left to do in order to decide how to order them. The ordering you want isn’t something strict like “most-recent first” or “alphabetically by title”. Instead it’s some much woolier notion of “best” or “most-relevant” first.

All of this means that SQL databases are generally not very good at full-text searches. Fortunately, other types of database are, including one called Elasticsearch. Elasticsearch is often described as a document-oriented database. We don’t need to go into the details of how exactly it works, but the important part for us is that, unlike SQL databases, Elasticsearch is very good at taking queries like “second-hand TV” and returning a list, ordered by “relevance,” of the fuzzy matches that users have come to expect from their search engines.

“Sounds like Elasticsearch is just better than SQL,” you might say. “Should we throw away our SQL databases and put everything in Elasticsearch instead?” Not so fast. Elasticsearch, and other databases like it, have their strengths, but they also have their weaknesses. They’re typically somewhat less reliable than SQL databases, and are somewhat more likely to accidentally lose data at large scale. They’re also often much slower to write new data to.

As we’ve already noted, there’s rarely a single, universally “best” tool for any type of job. There’s certainly no such thing as “the best” database. Instead, different databases have different strengths and weaknesses, and different solutions are appropriate for different tasks. At Steveslist, we care so much about making sure that we use the right tool for the right job that we store our data in both a SQL database and a document-oriented database like Elasticsearch.

We use our SQL database as our primary data store. It is our authoritative “source-of-truth”, and we write all our new data to it before we write it anywhere else. We do all our simple, precise reads from it, especially when accuracy and up-to-date-ness are our principal requirements. If we want to show a user a list of all their open listings, we read it from our SQL database. If we want to validate a users password, we read that from our SQL database too. This plays to the strengths of SQL databases.

However, in the background we also copy data from our SQL database into an Elasticsearch database, and send any full-text search queries made via our search box to Elasticsearch. This means that we benefit from the strengths of Elasticsearch, and are not impacted too much by its weaknesses. We copy over batches of records every few minutes, hours, or days, depending on the requirements of the specific dataset. Alternatively, we could watch the logs of our SQL database for new or updated records, and create or update the corresponding Elasticsearch records in near-realtime.

| | |

New data is always | |Queries for |Full-text search

written to the SQL | |specific data go |queries go to

DB first | |to the SQL DB too |Elasticsearch

V V V

+--------------+ +---------------+

| SQL Database +------>+ Elasticsearch |

+--------------+ +---------------+

New data is copied over from

the SQL DB to Elasticsearch

When scouting Steveslist’s competition, I noticed that when you create a new Craigslist listing it says “your listing will be visible in search within the next 15 minutes”. I’ll bet pesos to pizza that this is because their primary datastore is a SQL database, but their search box is powered by an Elasticsearch-like engine. Their pipeline for replicating data from SQL to search probably takes around 15 minutes, which they’ve decided (very reasonably) is an acceptable delay for their particular use-case.

We’ve said that Elasticsearch is somewhat less reliable than most SQL databases. If Elasticsearch accidentally loses a few of our records then they won’t appear in search results. This would be a shame that would make our product a bit worse, and we try our hardest to avoid it happening. However, it wouldn’t be a disaster in the same way that losing data from our primary data store would be. We only copy data over to Elasticsearch once it has been written to and safely captured by our source-of-truth SQL database, which is what really matters.

It’s 6pm, and the library is closing. A librarian tries to ask you to leave. Kate shoos him away with a barrage of crumpled-up balls of paper.

Internal tools

Managing the Steveslist platform requires bespoke internal tools. We need to perform a wide range of administrative tasks, like deleting listings that are too illegal (even for us), issuing refunds, viewing a user’s personal details in order to help with support requests, and so on. Many of these tools will be used by people who work on other teams at Steveslist, like finance, compliance, legal, sales, and support. Since the tasks they need to perform are so specific to the way that Steveslist works, we can’t do them using third-party tools, and have to build our own instead.

In the early days, we baked this functionality into the main Stevelist product and only exposed it to users who had the is_steveslist_employee = True database flag set. This was an OK approach for a small company, but was also fragile and easy to mess up. It was scary to think that we were exposing all of our superuser powers through the same servers that run our main product. It made the potential consequences of a security flaw in our application much worse, and created new types of mistake for us to make, such as forgetting to disable the is_steveslist_employee flag for an acrimoniously fired employee.

Once Steveslist reached a certain level of maturity, we built ourselves an entirely separate admin platform, with separate, hardened authentication and authorization. The service runs on entirely separate servers, and requires a VPN and a TLS client certificate to access (which we’ll talk about another day). This separated out our internal- and external-facing products, and drastically reduced the chance of a boneheaded error exposing our admin tools to the world. We’re frequently building new internal tools - one for user administration, one for server management, one for fraud detection, and so on. These services all talk to the same database as our user-facing products, so they all have access to the same data. They just run on different servers that are completely inaccessible to the outside world.

Cron jobs

There are lots of tasks that we’ll want our system to perform at fixed times and intervals. For example:

- Emailing ourselves weekly usage reports

- Sending marketing emails to users

- Charging the credit cards users who have a subscription plan with us

- Copying data from our SQL database to Elasticsearch

The most common tool used for running scheduled jobs is called cron, a tool that is built into Unix operating systems. It’s so common that people will often call any kind of scheduled job a “cron job”, even when it’s not actually being run by cron.

You can set up a cron job on your own computer by running:

crontab -e

Then typing into the prompt:

*/5 * * * * $YOUR_COMMAND

This will cause your computer to execute $YOUR_COMMAND every 5 minutes.

Steveslist currently has a very simple and slightly fragile cron setup. We have a single “scheduled jobs server”. We use crontab on this server (as above) to tell it the commands that we want it to run, and the schedule that we want it to run them on. This setup isn’t scaling very well - if the scheduled jobs server explodes or even hiccups then we don’t always know which jobs it did and didn’t run, and have to scramble to bring up a replacement server. And even though the server is very beefy and powerful, eventually we’re going to want to run more jobs than it can handle at once. We’re considering either splitting up our cron jobs into multiple servers, or setting up a new system using a modern tool like Kubernetes.

Pubsub

Actions have consequences. This is both the subject line of the sinister emails that we send to people who write mean things about us on the internet, and the reason we have a pubsub system.

When a new user signs up, we want to send them an email welcoming them to Steveslist and reminding them about the action-consequence relationship I just described. When a new listing is added for a stolen TV in San Francisco, we want to notify users who have set up search alerts for TVs in the Bay Area. When a card is declined for a subscription, we want to email the responsible user to politely threaten them. When a new listing is added, we want to perform some extremely cursory anti-fraud checks. When an item is purchased, we want to sent a webhook to its seller. And so on.

Technically, all of these actions could be performed synchronously (rememberer that word?) by the server executing the initiating action. However, this is often a bad idea, for two reasons. First, the response action (such as emailing all the users who are subscribed for notifications about new stolen TVs) may be very slow. Performing the response action synchronously means that if the initiating action was performed by a user then they will have to wait for all the response actions to finish too. This might not be the end of the world if the response action is small and quick, like sending a single email. But if it’s larger - like searching for and notifying all users who might be interested in a new item - then, well, it still won’t be the end of the world, but it will be a bad user experience.

To mitigate this problem we have built a “publish-subscribe” or “pubsub” system. When a trigger action is performed, the code that performs it “publishes an event” describing the action, such as NewListingCreated or SubscriptionCardDeclined. The words “event” and “publish” are quite loosely defined in this context, and don’t have a rigorous technical definition. An event is just some sort of record of something that happened, and to publish an event just means that you somehow make a note that something happened. The details of how you do so depend entirely on the pubsub system in question. In a simple system events might be stored in tables in a SQL database, and code would publish events by writing new records to a table.

If a programmer at Steveslist wants a response action to be performed whenever a new event of a particular type is published, they can write a consumer. This is a piece of code that “subscribes” to a type of event, and which is executed whenever a new event of that type is published. It uses the details of the event (for example, the user whose subscription payment failed) to asynchronously execute whatever actions the programmer wants (for example, sending the user a menacing email).

Pubsub systems are often managed by a central message broker. Systems publish events to the broker, and the broker is then responsible for getting the events to any subscribed consumers. This can be achieved using either a push or a pull mechanism. Consumers can pull messages from the broker by polling it and repeatedly asking “any new events? any new events?” or they can wait and listen and the broker can push notifications of new events out to them, for example by sending them an HTTP request.

1. New user signs|

up to Steveslist |

v

+-----------------+ +------------------------+

|Steveslist Server| +-->+SendWelcomeEmailConsumer|

+---------+-------+ | +------------------------+

| v

2. Server reports| +-------------++ 4. Consumers send welcome

a NewUserSignup +---->+Pub/Sub Broker| emails, check for spam,

event to the +-------------++ etc.

Pub/Sub system ^

3. Pub/Sub broker | +------------------------+

notifies consumers +-->+NewUserSpamCheckConsumer|

that have subscribed to +------------------------+

NewUserSignup events.

Pubsub systems have many benefits:

- Non-critical actions are performed asynchronously, keeping the user experience snappy

- Our code is kept clean and well-separated. The code that publishes an event doesn’t have to care about what the events’ subscribers do in response

- If a subscriber’s action fails for some reason (for example, the email-sending system has a hiccup), the pubsub system can note this failure and retry again later

Next, let’s talk big data.

Big data and analytics

In order to understand and optimize our business, we need to be able to calculate complex statistics across the entire Steveslist platform. How many listings are created every day, segmented by country and city? How many users who signed up each month have created a listing within 90 days of signing up?

To do this, we need to write database queries that aggregate over the entirety of our data. We don’t want to run these queries against our production SQL database, because they could put an enormous amount of load on it. We don’t want a huge query issued by an internal analyst to be able to bring our production database to a grinding halt, but we do want to provide this analyst with a tool that is well-suited to their needs. To complicate matters further, database engines that are quick at small queries (like returning all the listings belonging to a single user) are typically unacceptably slow (or indeed incapable) of answering giant queries (like calculating the total dollars spent on listings in each category, per day, for the last 90 days).

Despite this, for the first year or so after Steveslist was founded, we took a risk and simply ran our analytics queries against the main production database. This was a gamble, but it just about worked. We didn’t have much data anyway, and we had more important things to focus on, like attracting the customers who would create the big data that would one day mean that we had to find a more scalable solution.

Eventually we did bring down the production database with an overly-ambitious query, and decided that the time had come to invest in a data warehouse. A data warehouse is a data store that is well-suited to large, system-wide queries. Our warehouse is powered by a database engine called Hive, but we could also have chosen Presto, Impala, Redshift, or any number of competing alternatives. Hive accepts queries written in SQL, but is much better at executing these queries against giant datasets than our MySQL database is.

We replicate our data from our production SQL database to Hive, once a day, overnight. Steveslist analysts and programmers can query the same dataset using whichever database engine best suits their needs. They can use the production SQL database for small, precise, source-of-truth queries from production systems; Elasticsearch for full-text search queries; or the data warehouse for huge queries that aggregate over vast volumes of data.

It’s dark outside and you’re hungry. Is that pretty much it? you ask.

“Oh god no,” Kate replies, “we could keep going forever. But this is a pretty good start. It’s helpful to have a broad understanding of a wide range of topics, but no one needs to know the details about everything. I find that once you know some basics you can keep picking up more basics and even a couple of details as you go along.”

You ask if Kate could perhaps continue to elaborate on her five-year vision for Steveslist tomorrow.

“Absolutely,” says Kate. We’ll talk about more of what goes on inside a real, large online platform, including:”

Security

- HTTPS and other forms of encryption

- Two-factor authentication

- SAML

- Secret key management

Server management

- Deploying new code

- AWS and competitors

- Terraform

- Load balancers

- Containers

- Alerting when code breaks

Big data

- Map-reduce and other big data jobs

- Machine learning

- User tracking

“See you tomorrow at 7am?”

This post is part of my Programming for Advanced Beginners series. Subscribe now to receive specific, actionable ways to make your code cleaner, every other week, entirely free.

You’ve started yet another company with your good friend, Steve Steveington. It’s an online marketplace where people can buy and sell things and where no one asks too many questions. It’s basically a rip-off of Craigslist, but with Steve’s name instead of Craig’s.

You’re going to be responsible for building the entire Steveslist technical platform, including all of its websites, mobile apps, databases, and other infrastructure. You’re excited, but also very nervous. You figure that you can probably cobble together a small website, since you’ve done that a few times before as part of your previous entertaining-if-morally-questionable escapades with the Stevester. But you have no idea how to even start building out all of the other infrastructure and tools that you assume lie behind large, successful online platforms.

You are in desperate need of a detailed yet concise overview of how real companies do this. How do they store their data? How do their different applications talk to each other? How do they scale their systems to work for millions of users? How do they keep them secure? How do they make sure nothing goes wrong? What are APIs, webhooks and client libraries, when you really get down to it?

You send a quick WhatsApp to your other good friend, Kate Kateberry, to see if she can help. You’ve worked together very effectively in the past, and she has decades of experience creating these types of systems at Silicon Valley’s biggest and most controversial companies.

She instantly accepts your job offer. You had actually only been ringing for some rough guidance and a good gossip, but you nonetheless instantly accept her acceptance. No point looking a gift horse in the mouth, even when you don’t have any money to pay her. Kate proposes that her first day be 5 weeks ago in order to help her smooth over some accounting irregularities. She can come into the office sometime next week. You feel encouraged and threatened by her eagerness.

Kate bounces into your offices in the 19th Century Literature section of the San Francisco Public Library. “OK let’s do this!” she shouts quietly. “What have we got so far? How are all our systems set up? What’s the plan?” You lean back in your chair and close your laptop, which was not turned on because you have left your charger at home. You steeple your fingers in a manner that you hope can be described as “thoughtful”.

“Let me flip that question around, Kate. What do you think the plan should be?”

Kate takes a deep breath and paints an extremely detailed vision of the Steveslist platform five years into the future and the infrastructure that will power it.

Before we start (says Kate), I want to make it clear that I’m not saying that any of this is necessarily the “right” way to set up our infrastructure. If someone you trust more than me says something different then you should probably do what they say. There are many tools out there, each with different strengths and weaknesses, and many ways to build a technology company. The real, honest reasons that we will make many of our technological choices will be “we chose X because Sara knows a lot about X” and “we chose Y on the spur of the moment when it didn’t seem like a big decision and we never found the time to re-evaluate.”

Nonetheless, let’s fast-forward five years into the future. Now Steveslist has two main consumer-facing products:

- The Steveslist web app

- The Steveslist smartphone apps

These are the main ways in which users directly interact with the Steveslist platform. In addition, we also provide an API that allows programmers to build power-tools on top of the Steveslist platform that, for example, create listings for hundreds of items programmatically. To support this, we offer:

- A Steveslist API

- Steveslist API client libraries that make it easy for programmers to write code that talks to our API

Here, I’ll draw a diagram on the whiteboard:

+-----------+ +--------------+ +-----------------+

|Web Browser| |Smartphone App| |Client Libraries/|

+-----+-----+ +------+-------+ |Other API code |

| | +-------+---------+

| v |

| +-----+------+ |

+--------->+ Steveslist +<-----------+

| Servers |

+------------+

Finally, we have many, many services running in the background that provide the data and power to these external-facing applications:

- Webhooks - to notify users when something happens to their account, such as “order placed”

- User password authentication - to securely log users in

- SQL database - the main Steveslist data store. Needs to be highly scalable and reliable

- Free-text searching system - to power the search box where people can look for broad search terms like “TVs” or “motorbikes”

- Internal tools - to help us administer the Steveslist platform, and to take actions like issuing sternly-worded warnings to malicious users

- Cron jobs - to run regular tasks that do anything from generating invoices, to billing customers, to sending as much of our users’ data as possible to third-party ad networks

- “Pubsub” system - to allow us to take asynchronous actions on different trigger events (such as “when a new user signs up, send them a welcome email”)

- Big data analytics system - to allow us to run enormous queries over the entirety of Steveslist’s data

- And many more that we’ll talk about another day

Let’s go through each of these systems in turn. Let me know if anything isn’t clear, if you have any questions, or if you think I’ve got something wrong.

Before we start - what is a server really?

Before we start, let’s define some important terms. In fact, let’s just define one. We’re going to talk a lot about “servers” today. But what is a server, when you really get down to it?

For our purposes, a server is a computer that runs on a network and listens for communications from other computers. When it receives some data from another computer it performs some sort of action in response and - usually - sends back some data of its own. For example, a web server listens on a network for HTTP requests and sends back webpages and information in response. A database server listens for database queries and reads and writes data to the database that it is running.

This brief description skips out entire degrees and careers of detail, and there are of course far more precise and accurate ways to define the word “server”. But this should get us through until dinnertime. What did you say? What’s a “network” really? A good question for another day.

Now we’re ready to talk about the Steveslist platform.

Steveslist web app

This is the main Steveslist product. It’s just a normal web app, very similar to any website that you’ve built before, except much bigger. It’s a modern “single-page app” (SPA). The “single” in “single-page app” refers to the fact that the user’s browser almost never has to fully reload the page as the user clicks around our site. Instead, when the browser makes its first HTTP request to our servers, we send it back a basic, skeleton HTML page and a big pile of JavaScript code. This JavaScript code executes inside the browser, and updates the view of the page in response to the user’s actions. When the JavaScript wants to send or retrieve data from Steveslist, it sends an Asynchronous JavaScript XML Request (almost always called AJAX for short) in the background to a URL. When our server responds, the JavaScript uses the response to update the browser view accordingly.

+----------+1.User's browser visits steveslist.com. +----------+

| | It sends an HTTP request to the | |

| | Steveslist servers | |

| +--------------------------------------->| |

|User's Web| |Steveslist|

| Browser |2.Steveslist server responds with a | Servers |

| | skeleton HTML page that instructs the | |

| | browser to request additional | |

| | JavaScript files. | |

| |<---------------------------------------+ |

| | | |

| |3.User's browser requests and receives | |

| | these JavaScript files from the | |

| | Steveslist server. | |

| +--------------------------------------->| |

| |<---------------------------------------+ |

| | | |

| |4.User's browser executes the JavaScript| |

| | code. The code sends more requests for| |

| | the user's data to the Stevelist | |

| | server, and updates the browser UI to | |

| | display it. | |

| +--------------------------------------->| |

| |<---------------------------------------+ |

+----------+ +----------+

robertheaton.com is not a single-page app. Whenever you click on a link, the browser has to reload the entire page. twitter.com is a single-page app. Whenever you click on a link, the browser dynamically updates a small portion of tthe page without forcing a full refresh.

SPAs are a lot of work to build and maintain, but they sure look good.

Steveslist smartphone apps

We provide Steveslist smartphone apps for both iOS and Android. They are conceptually very similar to our single-page web app. Both our smartphone and web apps make HTTP requests to our servers. Then our servers receive these requests, do some work and return an HTTP response. Finally, both our smartphone and web apps update their display in order to communicate with the user.

Since our smartphone apps are performing the same operations as the web app (for example, create listing, send message, etc), they can usually even send their requests to the exact same URLs as the web app. The only extra work that we have to do is to develop the frontends of the apps themselves. Some frameworks even make it possible to write mobile apps using JavaScript, allowing you to reuse code and logic across platforms.

Steveslist API

We allow users and third-parties to write code that programmatically interacts with our platform. In the same way that people can use the Twitter API to write code that reads; likes; and creates Tweets, we allow them to use the Steveslist API to search; buy; and list items.

Programmers use our API by writing code that makes HTTP requests to our API endpoints. For example, in order to retrieve a list of all their listings, the programmer sends an HTTP GET request to api.steveslist.com/v1/listings. We respond with the data they requested, formatted as JSON. JSON stands for JavaScript Object Notation, but JSON is not specific to JavaScript and can easily be interpreted by any programming language. A JSON response to a request to retrieve all of a user’s listings might look something like this:

{

"listings": [

{

"id": 2178123867,

"name": "Stolen TV",

"country": "US",

"city": "San Francisco",

"price_amount": 1000,

"price_currency": "usd",

# etc...

},

{

"id": 182312679,

"name": "Stolen Bicycle",

"country": "US",

"city": "San Francisco",

"price_amount": 2000,

"price_currency": "usd",

# etc...

}

]

}

This structured response format is very easy for a program to parse, which means that the code that made the request can trivially interpret and use the data from our API.

Users identify or authenticate themselves to our API using an API key. This is, roughly speaking, the API equivalent of a password. It is a long, random string that we generate and display on a user’s “Settings” page. Users include their API key as an HTTP header with every HTTP request that they (or their code) makes to the API. When we receive an API request we check to see whether the attached API key corresponds to a Steveslist user. If it does then we perform the request on behalf of that user.

If a programmer wants to, they can manually build HTTP requests to our API themselves, using their language’s standard HTTP library. For example, in Python they might write:

import requests

url = 'https://api.steveslist.com/v1/listings/'

listing_params = {

"name": "Stolen TV",

"country": "US",

"city": "San Francisco",

"price_amount": 1000,

"price_currency": "usd",

}

api_key = "YOUR_API_KEY_GOES_HERE"

response = requests.post(

url,

data=listing_params,

headers={"X-Steveslist-API-Key": api_key},

)

However, we make life easier for programmers by providing client libraries.

Steveslist client libraries

A client library is a library that “wraps” the functionality of the Steveslist API. This means that anyone using the client library doesn’t need to know anything about the fine details of the Steveslist API. Instead, they can just write:

import steveslist

listing = steveslist.Listing.create(

name="Stolen TV",

country="US",

city="San Francisco",

price_amount=1000,

price_currency="usd",

api_key="YOUR_API_KEY_GOES_HERE"

)

Our libraries turn the parameters that they are given into appropriately formatted HTTP requests, which they send to the Steveslist API as normal. We’ve written client libraries for every major programming language that we could think of, and they are by far the most common way that people interact with our API.

Webhooks

We’ve seen how Steveslist users can use our API to programmatically interact with their account. In addition, many users also want us to proactively tell them whenever something happens to their Steveslist profile. For example, suppose that someone wanted to fully automate the process of selling items on Steveslist. Whenever a customer pays for an item using our new, mostly-secure StevePay system, they want to send the customer a thank you email and automatically instruct their warehouse to ship a stolen TV to the order address. Our seller could constantly and repeatedly query the Steveslist API asking “Any new sales? Any new sales?” However, this would be very inefficient, and would put a lot of unnecessary load on our servers.

Instead, we provide an industry standard system called webhooks. A webhook is an HTTP request that we send to our users whenever something interesting happens to their account. It contains all the data describing the event that just happened - for example, the item ID, the price, the buyer ID, buyer address, and so on. Webhooks allow users to automatically perform response actions, such as the aforementioned email and auto-shipping.

To use webhooks, the user tells us the URL to which they would like us to send their webhooks (for example, steveslistwebhooks.robertheaton.com. They set up a web server at that URL that will receive and action these webhook notifications.

1.Buyer purchases an 3.The seller's server receives the webhook,

item as normal. and uses the information in it to

automatically process the order.

+---------------+ +-----------------+

|Buyer's Browser| |Seller's Webhook-+

+------+--------+ |Receiving Server |

| +------+----------+

| ^

| |

| |

| +-----------+ |

+--->+ Steveslist+----------+

| Server |

+-----------+

2.Once the transaction has been completed,

Steveslist looks up the seller's

webhook URL (if set). We then send

an HTTP request to this URL,

containing the details of the purchase.

The user deploys code on their web server that performs the appropriate response actions whenever it receives a webhook from us. We don’t only send webhooks when an item is purchased - we also send them when a user receives a message; when one of their items is removed by an admin; or when a buyer makes a complaint. This enables Steveslist sellers to automate not just the listing of items, but also the selling and shipping of them too.

Webhook complications

Webhooks come with two main complications - security and reliability. First, let’s talk security. The endpoint to which the seller instructs us to send their webhooks is accessible to anyone on the internet. Anyone who knows the URL can send it fake webhooks, and if our seller isn’t careful this could allow an attacker to trick them into, for example, sending the attacker free stuff. A seller’s webhook URL should be difficult to find, since the seller won’t publicize its existence, but obscurity is not the same as security.

To allow our sellers to verify that a webhook really was sent by Steveslist, we cryptographically sign our webhook contents.

Cryptographic signing

Cryptographic signing is a deep and subtle topic. Here’s a condensed version of how we use it to secure our webhooks.

When a seller enables webhooks for their account, we generate a random “shared secret key”. We tell the seller to copy this key over to their webhook-receiving server and keep it secure, so that its value is known only by us and the seller. Whenever we send a webhook, we take this shared secret, combine it with the contents of the webhook by using a cryptographic hash function called HMAC, and get back a long, random-seeming, but entirely deterministic “signature” for the webhook.

Webhook contents +----------+

(eg. {"id": 123...}) |

v

+---+----------+

|HMAC Algorithm|----->Webhook signature

+---+----------+

^

Shared secret key |

(eg. 123mhu23jy8xdwgmd...)+---+

We include this signature in our webhook body, for example:

{

"action": "item_sold",

"price": 100,

// ...more params...

"signature": "234gj98d49j834978gf39t78ndn98g7dq3ng897308y7"

}

When the seller’s webhook-receiving server receives a webhook, it takes the shared secret and webhook contents and calculates what it expects the signature to be in exactly the same way that we did. It compares the result to the signature attached to the webhook; if they match then it accepts and processes the webhook. Since the signature can only be generated using the shared secret known only by us and the seller, the webhook-receiving server can be confident that the webhook was sent by us. If the signatures don’t match, however, the server rejects the webhook.

Note that all of the signature verification code must be written and maintained by the sellers. We can provide them with encouragement and examples, but we can’t force them to verify signatures correctly, or even at all. For some real-world examples, look at how Stripe and GitHub sign their webhooks.

Reliability

We also need to consider what happens when our webhooks go wrong and what guarantees we want to make to our users about them. If we try to send a webhook but can’t connect to the user’s server, what should we do? What if we successfully connect to their server and send the webhook, but their server sends back an error? What if we send the webhook but the server hangs for twenty seconds before disconnecting without telling us what happened?

There are tradeoffs involved here that require clear communication and a surprising amount of infrastructure to manage. We at Steveslist choose to guarantee that we will deliver webhooks “at least once”. This means that if a webhook fails to send then we will keep trying (a large but not infinite number of times) until it does. If we’re not sure whether a webhook succeeded or failed, we will keep trying until we are sure that an attempt has succeeded. This might occasionally result in us sending the same webhook twice, but it’s the seller’s responsibility to have their code handle this gracefully instead of sending the same customer five stolen TVs instead of the one that they ordered.